This repository is a research on Minimum Steiner Trees completed in fulfilment of Discrete Mathematics and Design & Analysis of Algorithms courses.

For the Discrete Mathematics research, the team members were:

-

Ajay Sharma

-

Ajinkya Bedekar

-

Aman Garg

-

Althaf

-

Abhinav Reddy

-

Srinath

For the Design & Analysis of Algorithms research, the team members were:

-

Abhijit Bhupendra Singh

-

Aetukuri Srinath

-

Ajay Sharma G S

-

Ajinkya Bedekar

-

Aman Garg

-

Anirudh Sharma

The repository consists of the following:

-

Research papers and lessons on Minimum Steiner Trees, and Properties and Algorithms for Minimum Steiner Tree Problem

-

Mid Term and Final Reports for the research

-

Presentations of the project

-

Complexities of different available algorithms

-

Test of developing algorithms

-

Image of k-chain algorithm

-

Example of algorithm

Sample paper for references, sections and subsections:

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1504.05140.pdf

Some useful information on k-chain algorithm:

Definition of k-chain

A k-chain for a positive integer n is a sequence of natural numbers v

v=(v(0),…,v(s))k,

with v(0)=1, v(s)=n, and v(i)=∑k−1h=0v(ih) for all 0<i≤s and −1≤ih<i with v(−1)=0; i.e., each term in v is the sum of k previous terms (including zero). The number s is called the length of the k-chain.

There are many connections between addition chains and k-chains. They are as follows:-

1. An addition chain can be derived from each k-chain with k>2.

The Length of an Optimal k-Chain

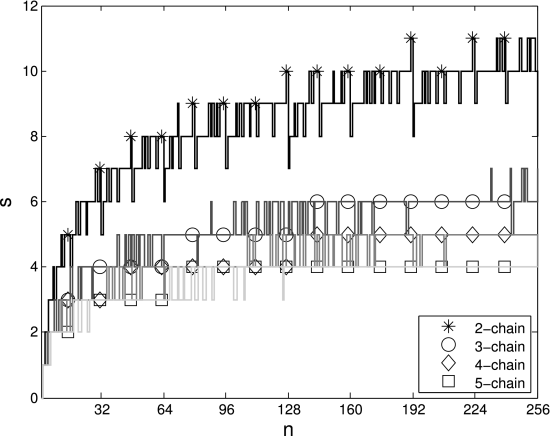

Optimal k-chains can be found efficiently with the backtracking algorithm originally proposed for addition chains and optimized for k-chains. The figure, given below plots the lengths of optimal k-chains for 2≤k≤5 and 1≤n≤256. This clearly shows the reduction of lengths when k increases. Hence, if an application using addition chains can exploit k-chains instead of addition chains, then results (typically, computation latency) are likely to improve significantly.

A Proposition Based on K-Chains

Let v0 be an optimal k0-chain of length s0 for an integer n. If k1>k0, the length s1 of an optimal k1-chain v1 for n satisfies s1≤s0.

Proof.

An optimal k1-chain cannot be longer than an optimal k0-chain because each -chain is also a k1-chain. The k1 -chain v1 can be constructed by setting v1(i)=∑k0−1h=0v0(jh)+∑k1−1h′=k0v1(−1); i.e., by adding k1−k0 zeros to all v0(i).

Consequently, an optimal k0-chain is not necessarily an optimal k1-chain but if an optimal k1-chain is also a k0-chain, then it is always an optimal k0-chain.

SOME ALGORITHMS FOR K_CHAINS

A k-ary algorithm for finding a k-chain for an integer n

Input:

k, n=∑ℓi=0niki=⟨n0,n1,…,nℓ⟩k where ℓ=⌊logkn⌋

Output:

A k-chain v for

v(i)←ki for 0≤i≤ℓ

j←1;

for all xi>0 in x={n0,n1,…,nℓ−1,nℓ−1}do

v(ℓ+j)←v(ℓ+j−1)+xiv(i)

j←j+1

return v

While addition chains derived with all variations of the binary method (e.g., left-to-right or right-to-left) have the same length, it is possible to derive different variations of the k-ary algorithm so that the lengths of the resulting k-chains differ. In the following, we propose a variation which constructs k-chains that are at least as short as the ones provided by Algorithm 1 and the variation considered in [10]. As a consequence, we can also use this new algorithm for improving the upper bound of Proposition 3.

An Algorithm for Finding Short k-Chains

Even though backtracking algorithm allows finding optimal k-chains relatively efficiently, finding optimal k-chains for an arbitrary large n becomes impractical, especially, if it needs to be done on-the-fly. Hence, we propose a simple procedure for finding short, but not necessarily optimal, k-chains. It is another k-ary generalization of the well-known binary method and it is captured in Algorithm 2. The algorithm constructs a temporary vector t which contains the indexes of v(i)=kiwhich are to be summed. Then, t is processed so that k values are always summed in calculating each (excluding the last one if the number of summands is not a multiple of k ).

2. Another k-ary algorithm for finding a k-chain for a positive integer n

Input:

k, n=∑ℓi=0niki=⟨n0,n1,…,nℓ⟩k where ℓ=⌊logkn⌋

Output:

A k-chain v for n

v(i)←ki for 0≤i≤ℓ

j←0

for all xi>0 in x={n0,n1,…,nℓ−1,nℓ−1} do

(tj,tj+1,…,tj+xi−1)←(i,i,…,i)

(tj,tj+1,…,t⌈j/(k−1)⌉(k−1)−1)←(−1,−1,…,−1)

for i=0 to ⌊j/(k−1)⌋ do

\!v(ℓ+i+1)←v(ℓ+i)+v(ti(k−1))+v(ti(k−1)+1)+⋯+v(ti(k−1)+k−2)

return v

3. Chains and Inversions in GF(2m)

Fermat’s Little Theorem provides means for computing inversions in finite fields via exponentiations with a constant exponent. In GF(2m), the inverse element of A≠0∈GF(2m) is received through the following exponentiation:

A−1=A2m−2=B2m−1−1,whereB=A2

Because 2m−1−1=1+2+22+⋯+2m−2, the traditional binary method for exponentiations performs badly and requires m−2 multiplications and m−1 squarings. Itoh and Tsujii (IT) proposed a clever technique that reduces the number of multiplications to ⌊log2(m−1)⌋+h2(m−1)−1. Takagi et al. presented that improvements can be achieved in cases where m−1 has a ‘nice’ factorization. Recently, Dimitrov and Järvinen [19]proposed algorithms based on double-base and triple-base representations of m−1 that slightly improve the number of multiplications and provide certain implementation specific advantages over IT. It is also known that an inversion algorithm for GF(2m) can be derived from any addition chain for m−1 and using an optimal addition chain leads to an optimal number of multiplications.

Some Applications for k-Chains

It is widely known that addition chains can be used for computing general exponentiations An . Similarly, 3-chains and HD multipliers can be used for computing general exponentiations An , where A∈GF(2m) and n is an arbitrary positive integer. The special structure of n in the case of inversions, where n=2m−2, allowed one to find an efficient algorithm directly for an entire nbecause it was enough to find an optimal k-chain for m−1 which is small. Unfortunately, n is typically very large in practical applications which often prevents one from finding an optimal 3-chain for an entire arbitrary n. If n is predefined, it is possible to derive an optimal, or at least piecewise optimal, result offline and use it for efficient exponentiation by hardcoding it. Another option is to find a short, but probably sub-optimal, 3-chain using Algorithm 2. The use of even these suboptimal 3-chains instead of regular binary addition chains results in significant speedups for general exponentations An if an HD multiplier is available: the exponentiation requires ⌊log3n⌋+⌈(d3(n)−1)/2⌉ double multiplications instead of ⌊log2n⌋+h2(n) multiplications. General exponentiations can be accelerated also by using parallel 3-chains and, in that case, the latency reduces to only ⌈log3n⌉ double multiplications.

The proposed techniques based on 3-chains can have importance in basically all applications that require exponentiations (or specifically inversions) in binary fields. Speeding up pseudo-random number generation (PRNG) using inversions in finite fields is an example of this. In [24], Eichenauer-Herrmann and Niederreiter proposed a PRNG scheme where a sequence of pseudo-random numbers is retrieved from γi∈GF(q) defined by the recursion.

γi=αγ−1i−1+β,i≥1

Clearly, the computational cost of the scheme is dominated by the inversion: γ−1i−1=γ2m−2i−1.

Eichenauer-Herrmann and Niederreiter proposed using GF(2m) with an optimal normal basis such that m is reasonably close to a power of two. The suggested m are collected in Table 6together with the costs of inversions using IT that was suggested in [24] and an optimal 3-chain. Clearly, using optimal 3-chains and HD multipliers would allow significant reductions (between 17-50 percent) in the latency of the PRNG scheme introduced.

Coparison of Binary, Binomial, and Fibonacci Heaps:

Complexities:

k-chain Algorithm: