The purpose of this repository is to include Dapr, in an Azure App Service Environment (ASE). This is an exploratory solution, intended to find ways to add the covenience of Dapr in the already well-established ASE ecosystem.

-

Using App Service built-in support for docker-compose (see subdirectory):

- Advantages : Very simple

- Result : Numerous networking-related options aren't supported yet, reproducing a "sidecar-like" interaction is not possible at the moment

-

Making the main app process launch the Dapr runtime (daprd) (see subdirectory)

- Advantages : Compatible with non-containerized workloads

- Result : Although the "sidecar" is working, ASE does not allow for HTTP/2.0 (what GRPC is based on). However, in Dapr, Sidecar to sidecar communication must be over GRPC. Thus, this won't work at the moment.

-

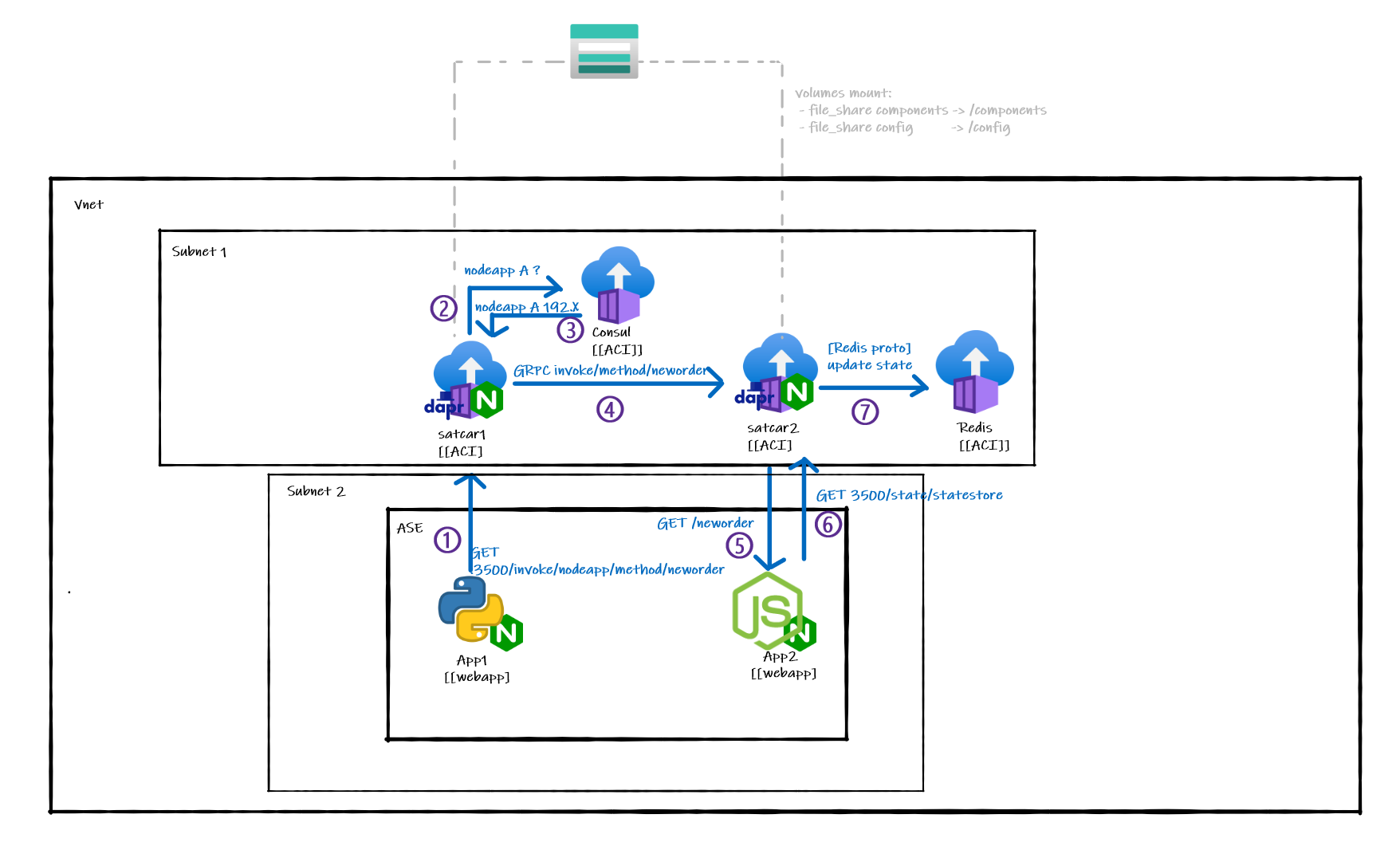

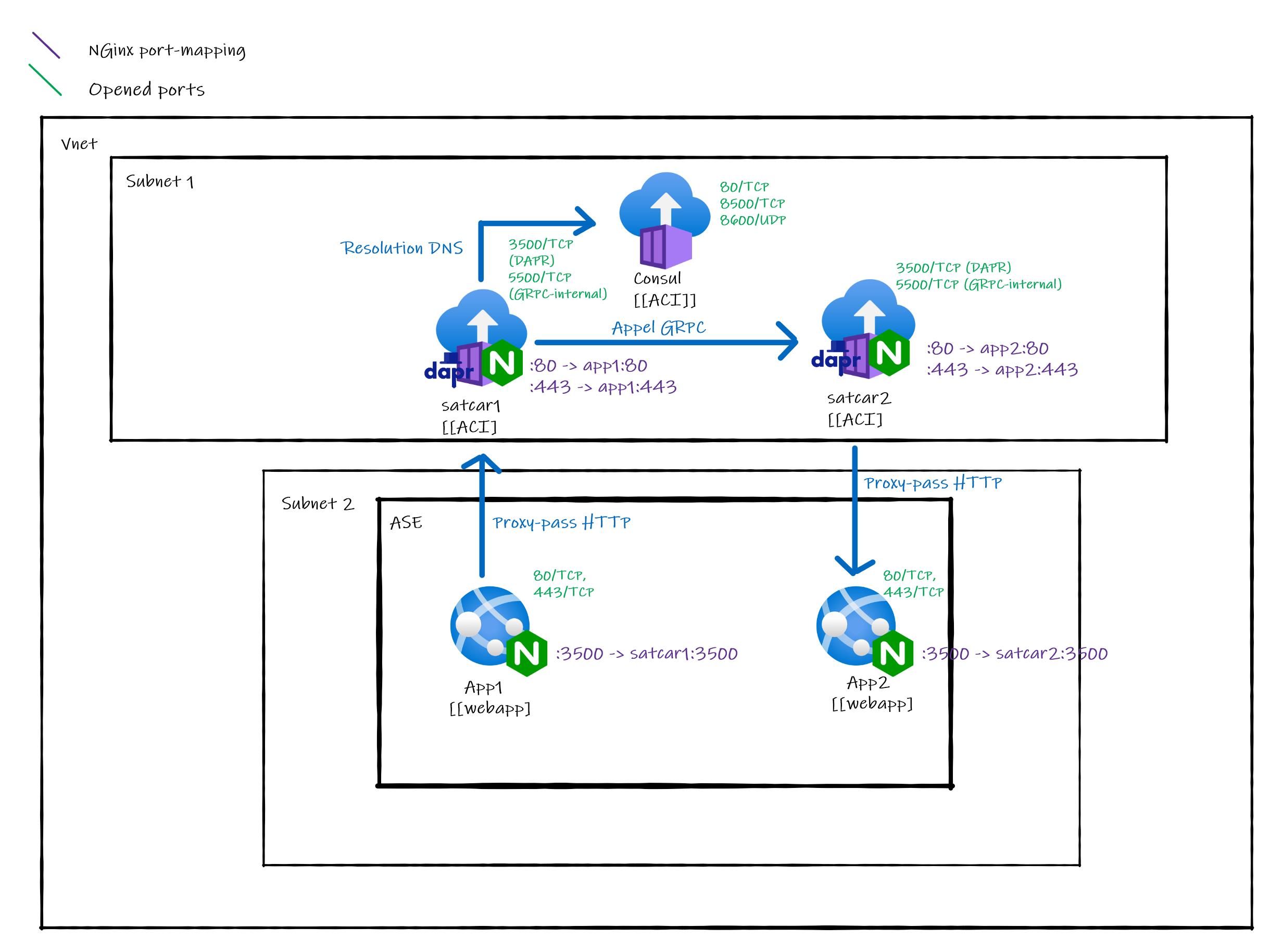

Externalizing sidecars using Azure Container Instances (ACI)

- Advantages : A lot easier to see sidecar state

- Result : This is the chosen approach. Externalizing sidecar allows for sidecar to sidecar communication to work without any problems. However, a sidecar should be using the same localhost interface as the process its helping. To run a sidecar is a separate service altogether, some proxies are used. This may have some performances impact (see viability and performances considerations). As these helpers processes aren't at the main process side anymore, but more of a "satellite processes", they'll be called from now on satcars.

The chosen solution is to externalize sidecars. As said earlier, this specific approach is meant to circumvent the HTTP2.0/GRPC incompatibility of ASEs. To allow for "localhost forwarding", a simple nginx reverse proxy is used both on the sidecar side and ont he main app side.

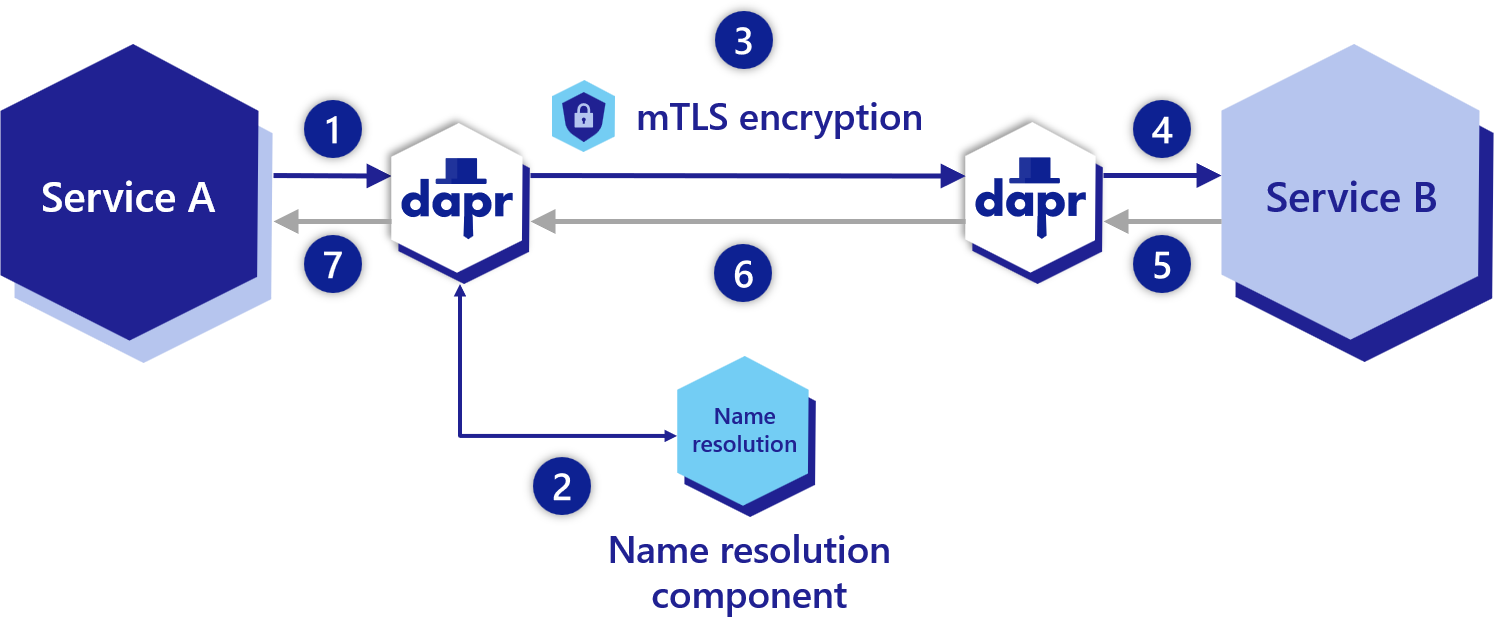

A normal Dapr service invocation is made in this way:

Service A is calling service B:

Service A is calling service B:

- Service A is calling its Dapr sidecar (using

HTTP/GRPCon localhost:3500) - Service A's sidecar is resolving the name of Service B to find its IP address (ore more precisely, the IP address of its sidecar) (using

mDNS by default) - Service A's sidecar is forwarding the request to Service B's sidecar (using

GRPC only) - Service B's sidecar is forwarding the request to Service B (using

HTTP/GRPCon localhost:[EXPOSED_APP_PORT]) - (The result goes all the way back to Service A)

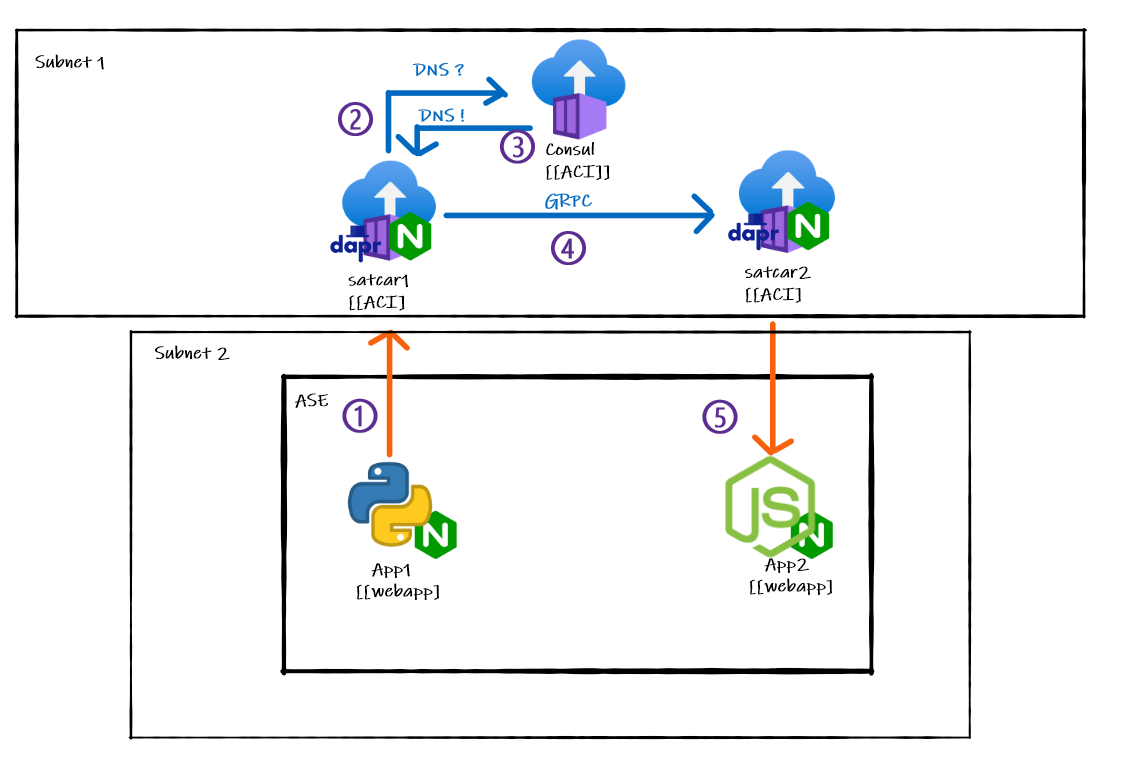

To reproduce the same workflow with externals sidecar, we have to tweak the architecture a bit :

App1 is calling App2:

App1 is calling App2:

- App 1 is calling its Dapr sidecar using

HTTPon localhost:3500. The HTTP call is then proxied to satcar1 by the Nginx process listening on localhost:3500. - satcar1 is resolving the name of App2 to find the IP address of satcar2 (which would normally be the same as the IP address of App2 but not in this case). mDNS can't be used on an ASE, so a separate Consul instance is used a name resolver using Dapr's name resolver component.

- satcar1 is forwarding the request to satcar2 (using

GRPC only) - satcar2 is forwarding the request to App2 (using

HTTP/GRPCon localhost:[EXPOSED_APP_PORT]) - (The result goes all the way back to App1)

All settings required to make Dapr work with this specific configuration are listed within the satcar README

To test this new workflow, a Pub/Sub demo app is used. This demo app is actually the hello-docker-compose sample of the Dapr repository.

The Python app wants to publish a state. It does so by calling the /neworder method on the NodeJS app. The node app is then persisting the stae in the Redis statestore, using Dapr as a layer of abstraction.

This demo app is demonstrating both service invocation and the use of bindings.

To configure both Dapr config and binding, a File Share hosted on an Azure Storage Account is leveraged. This ways, both satcar1 and satcar2 can share the exact same configuration without any duplication. This configuration could also be edited on the fly.

Three custom apps are used in this demo :

- Nodeapp (App2) see Readme

- Pythonapp (App1) see Readme

- Satcar (satcar1 and satcat2) see Readme

To run the demo app locally, you must have Docker and make installed. Then run :

# The OPTIMIZE flag can be set to 1.

# This will reduce the container final size by compressing the binaries (when applicable).

# This will however erase debug symbols, do not use it in development

# -j4 is optional, this will use multiple threads (4) to to the compiling/building.

# Stdout with -jX will be messy

make OPTIMIZE=0 -j4 run This will pull/build the necessary containers and start the apps.

By default, make run will end by attaching the current terminal to App2.

The following prompt should be visible

This means that the state created by App1 has successfully been persisted to the Redis instance using App2.

You can then stop the containers with

make stopYou can also push the nodeapp, pythonapp, satcar images to Dockerhub with the following command

make push DOCKERHUB_USERNAME=<YOUR_DOCKERHUB_USENAME>To deploy the app on Azure (using Terraform), use the following commands :

cd deploy

terraform apply The deployment will last 2 and a half hours or so (creating an ASE takes a long time).

Going from the Dapr Consul name resolution component spec, a working DNS configuration wan quickly be deduced :

# This file can be found in deploy/modules/demo/config/config.yaml.tpl

apiVersion: dapr.io/v1alpha1

kind: Configuration

metadata:

name: appconfig

spec:

nameResolution:

component: "consul"

configuration:

client:

# This is the only variable that has to be manually filled in

address: "${CONSUL_HOST}:${CONSUL_PORT}"

# Consul doesn't need to register itself

selfRegister: false

queryOptions:

useCache: true

daprPortMetaKey: "DAPR_PORT"

# All the variables of this section are automatically filled by Dapr at runtime

advancedRegistration:

# Filled with the Appid given at daprd as a command line switch

name: "${APP_ID}"

# Filled with the app port given at daprd as a command line switch

port: ${APP_PORT}

# Filled with the **PRIVATE IP** of the container daprd is running in

address: "${HOST_ADDRESS}"

# Full control over health check, failing an health check will

# unregister the app from consul

# check:

# name: "Dapr Health Status"

# checkID: "daprHealth:${APP_ID}"

# interval: "15s"

# http: "http://${HOST_ADDRESS}:${DAPR_HTTP_PORT}/v1.0/healthz"

meta:

DAPR_METRICS_PORT: "${DAPR_METRICS_PORT}"

DAPR_PROFILE_PORT: "${DAPR_PROFILE_PORT}"

tags:

- "dapr"This config is mostly the default configuration. The spec.nameResolution.configuration.client.adress attribute is filled in by Terraform on deployment, all other variables are filled in at runtime by Dapr.

On a side-note, on this peculiar configuration Consul isn't registering itself as a DNS entry (selfregister attribute). This isn't a requirement for the solution to work properly, its just not needed has the sidecars will always resolves consul with its IP.

It should however be noted that, as the sidecars are running in a separate service from the app its supporting, some options have a slightly different meaning from usual :

advancedRegistration.addressis not the main app address, it's the sidecar's. In an idiomatic sidecar deployment, the two addresses should be the same, but not in this case. Plus, Dapr is filling this attribute with the private IP of the service its running in. Although App Services running in an ASE do have a private address, requests using this address are blocked. Deploying Dapr directly on an ASE would require to change this attribute to resolve the FQDN of the container.advancedRegistration.checkis checking the container. In an usual deployment, the sidecar being healthy also attest the main app being healty. In this peculiar deployment, another check (multiple checks can be defined) could be added to actually check the main app state.

# This file can be found in deploy/modules/demo/bindings/pubsub.yaml.tpl

apiVersion: dapr.io/v1alpha1

kind: Component

metadata:

name: pubsub

spec:

type: pubsub.redis

version: v1

metadata:

- name: redisHost

value: ${REDIS_HOST}:${REDIS_PORT}

- name: redisPassword

value: ""Redis is used in the demo application as both a state store and a Pub/Sub broker. It is however not impacted by the special way the sidecar are running. The host and port are simply filled in by Terraform at deployment time.

As stated earlier, an Azure file share is used a a volume mount to share the configuration/bindings between all the Dapr instance. The reason a File Share is used over a Blob or any other file storage solution is simply that this is the only solution supported by Container Instances. The configuration is mounted in the /config folder and bindings are mounted in the /components folder, as shown the Terraform below.

resource "azurerm_container_group" satcar-python"{

...

container {

name = "satcar-python"

...

volume {

name = "components"

mount_path = "/components"

read_only = true

share_name = var.dapr_components_share_name

storage_account_name = var.st_account_name

storage_account_key = var.st_account_key

}

volume {

name = "config"

mount_path = "/config"

read_only = true

share_name = var.dapr_config_share_name

storage_account_name = var.st_account_name

storage_account_key = var.st_account_key

}

}

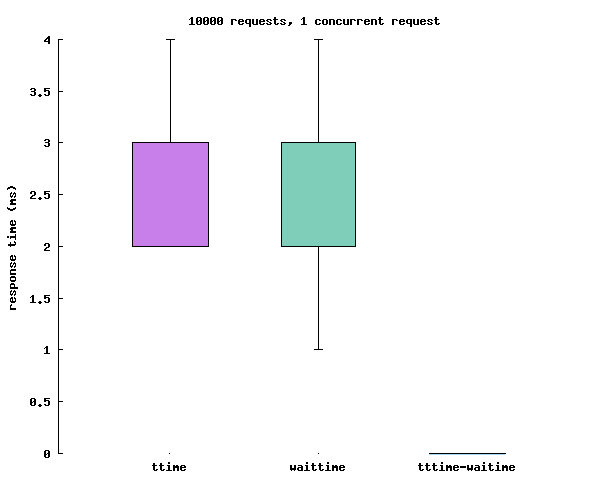

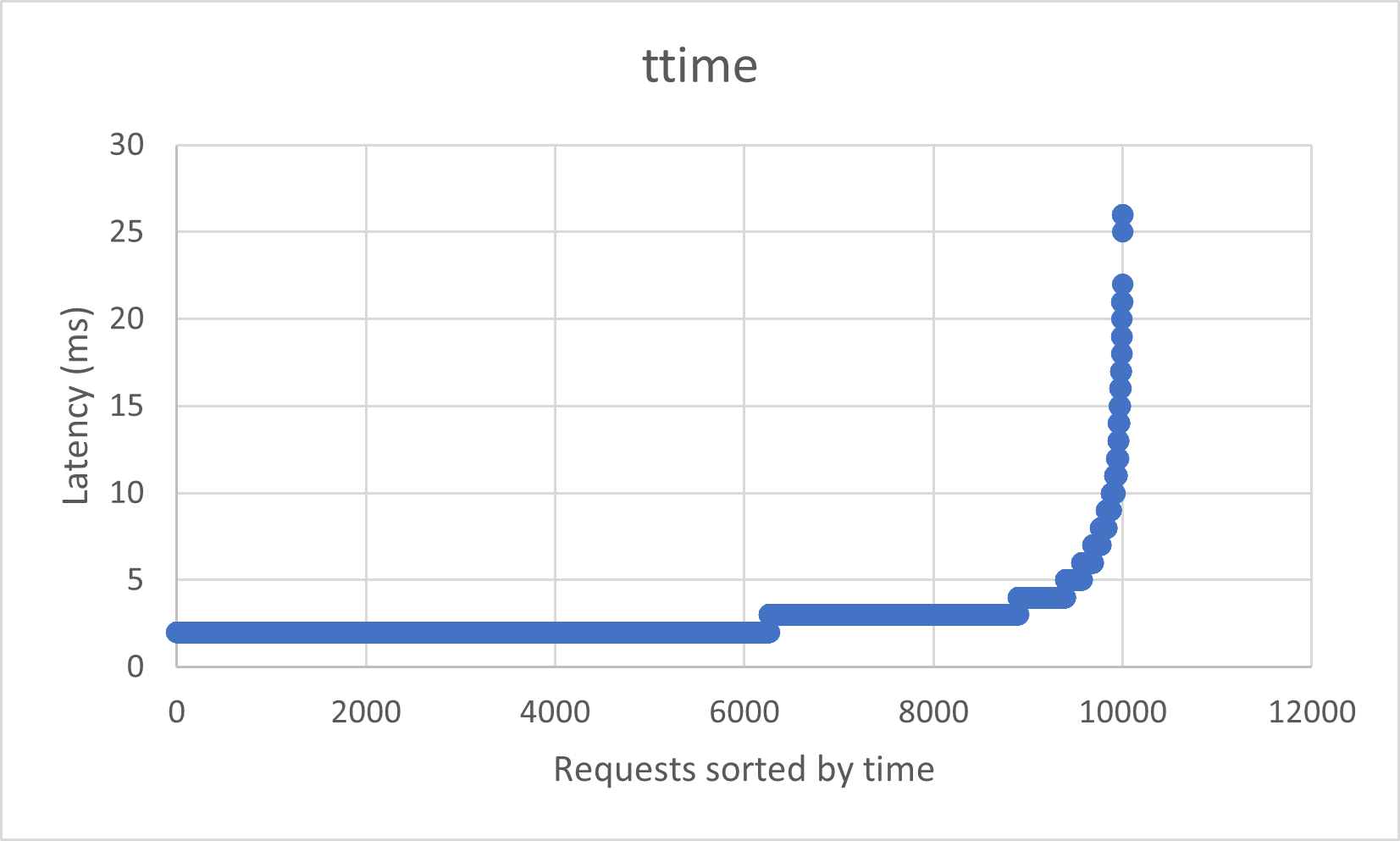

}Externalizing sidecars might have a performance impact. Every HTTP call between a container and its sidecar is now not a simple localhost call anymore, but has to get in and out of the ASE. This part will try to quantify this impact.

Simplifying the service invocation graph above, we can easily find the additional links that may have a performances penalty.

In a more traditional approach, the orange links should be localhost calls, these are the ones that we must measure.

On the other hand, the following calls are considered out of scope:

- Cross-sidecar GRPC : Not an additional call, plus there is no workflow modification whatsoever nor some redirection trick. Comparing this to its counterpart on a "classic" Kubernetes deployment would only compare Azure subnet to Kubernetes network.

- DNS resolution : Same as above. Including this would measure networks or pit mDNS/Consul/CoreDNS against each other.

Each DAPR process expose an health endpoint at /v1.0/healthz. This endpoint provide a consistent way to test the orange links, whilst preventing any caching mechanism, current or future, to affect the results.

As usual, the two way Round Trip Time (RTT) will be measured.

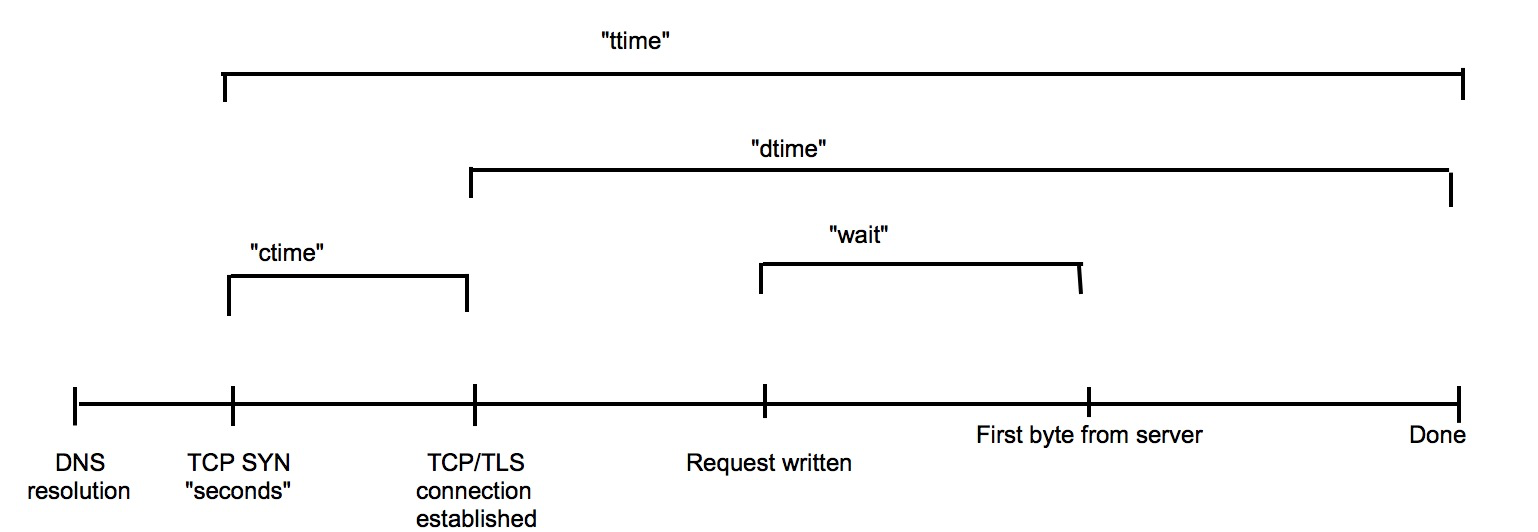

The software used for testing the latency of an HTTP call is Apache Bench. An Apache Bench is usually shown this way:

(Values are purely random)

| starttime | seconds | ctime | dtime | ttime | wait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| X | X | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

where starttime and seconds both are the time the call started. starttime being in an user-readable format, seconds being a timestamp.

The others columns can be understood that way :

- ctime is the time (in ms) to establish a proper TCP connection from the first SYN to the last SYN ACK.

- dtime is the time (in ms) to process the actual request

- wait is the time (in ms) spent waiting for the server to process the request before answering.

- ttime is the sum of the above

From this values, we can compute the raw network additional latency with ttime - wait

A very simple way to test is to SSH into either App1 or App2 and install the required softwares.

# Installing apache-bench and gnuplot to make a graph

apk add apache2-utils gnuplot curl

# Send 10 000 requests with a concurency of 1 and store the results

# in res.csv

ab -g res.csv -n 10000 -c 1 localhost:3500/v1.0/healtz

# Boxplot the results up

cat <<EOT > plot.p

set terminal png size 600

set style fill solid 0.5 border -1

set style boxplot nooutliers pointtype 7

set style data boxplot

set boxwidth 0.5

set pointsize 0.5

unset key

set border 2

set xtics border in scale 0,0 nomirror norotate autojustify

set xtics norangelimit

set ytics border in scale 1,0.5 nomirror norotate autojustify

set xtics ("ttime" 1, "waittime" 2, "tttime-waitime" 3) scale 0.0

set xtics nomirror

set ytics nomirror

set output "results.png"

set title"10000 requests, 1 concurrent request "

set ylabel"response time (ms)"

plot "res.csv" using (1):9, '' using (2):10, '' using (3):($9-$10)

EOT

gnuplot plot.p

# Convert image to base64, useful if you are on a web-based ssh session and copy files back and forth

cat results.png | base64

# Plug the base 64 into this site to get the image back :

# https://base64.guru/converter/decode/image

We get a mean latency of ~2.5ms per RTT. As the waittime is quasi-equal to the ttime, this may mean the actual additional network latency is negligible, and that using an actual sidecar should lead to the same results. However this is hypothetical as we can't compare to something that doesn't work yet.

The raw results in .csv format are available in the assets/data directory.

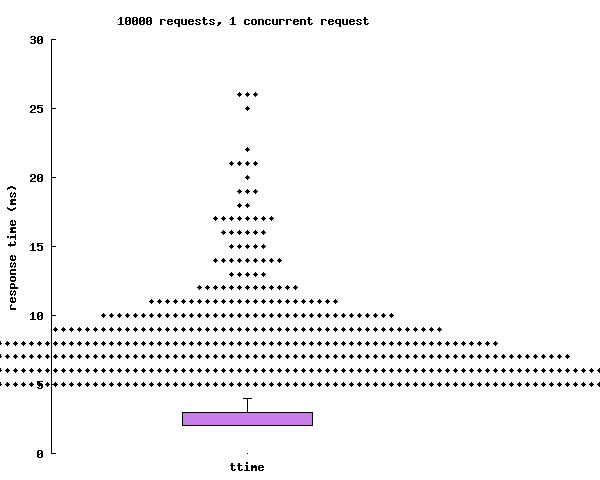

Factoring in outliers, the max latency seems to cap out at ~30ms.

This is however easily explained when visualizing the data with time as an axis.

The sheer number of request is overloading the container. Using more CPU resources for the ACI should fix this.