A Math Parser for Python

This repository contains a parser for simple mathematical expressions

of the form 2*(3+4) written in 92 lines of Python code.

No dependencies are used except for what can be found in the Python standard library.

It exists solely for educational reasons.

How to Use it

python3 compute.py '2*(3+4)'

and you should receive 14 as the result.

This is perhaps not so surprising, but you can also run

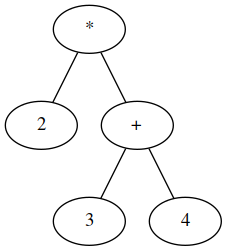

python graphviz.py '2*(3+4)' > graphviz_input

dot -Tpng graphviz_input -o output.png

to get a visual representation of the abstract syntax tree (this requires having Graphviz installed).

Related Work

@nicolaes ported this project to TypeScript and used it as a DSL for permissions.

Introduction

To my personal surprise, it seems that most mainstream languages nowadays are being parsed using handwritten parsers, meaning that no compiler generation tools such as ANTLR are used. Since a basic building block of almost all programming languages are math expressions, this repository explores building a handwritten parser for these simple math expressions.

This particular problem must have been solved millions of times by undergrad computer science students all around the world. However, it has not been solved by me until this date, as in my undergrad studies at TU Vienna we were skipping the low-level work and built a parser based on yacc/bison. I really enjoyed doing this small side project because it takes you back to the roots of computer science (this stuff dates back to 1969, according to Wikipedia) and I like a lot how you end up with a beautiful and simple solution.

Be aware that I am by no means an expert in compiler construction and someone who is would probably shudder at some of the things happening here, but to me it was a nice educational exercise.

The literature regarding this topic is very formal, which makes it a bit hard to get into the topic for an uninitiated person. In this description, I have tried to focus more on intuitive explanations. However, to me it is quite clear that if you don't stick to the theory, then you will soon run into things that are hard to make sense of if you cannot connect it to what's going on in the literature.

Problem

The problem is to bring algebraic expressions represented as a string

into a form that can be easily reused for doing something interesting with it,

such as computing the result of the expression or visualizing it nicely.

The allowed algebraic operations are +,-,*,/ as well as using (nested) parentheses ( ... ).

The standard rules for operator precedence apply.

LL(1) parsing

There are different ways how this problem can be tackled, but in general LL(1) parsers have a reputation for being very simple to implement.

An LL(1) parser is a top-down parser that keeps replacing elements on the parser stack with the right-hand side of the currently matching grammar rule. This decision is based on two pieces of information:

- The top symbol on the parser stack, which can be either a terminal or a non-terminal.

A terminal is a token that appears in the input, such as

+, while a non-terminal is the left-hand side of a grammar rule, such asExp. - The current terminal from the input stream that is being processed.

For example, if the current symbol on the stack is S and the current input terminal is a

and there is a rule in the grammar that allows

S -> a P

then S should be replaced with a P.

Here, S and P are non-terminals, and for the remainder of this document,

capitalized grammar elements are considered non-terminals,

and lower-case grammar elements, such as a are considered a terminal.

To continue the example, a on top of the stack is now matched to the input stream terminal a

and removed from the stack.

The process continues until the stack is empty (which means the parsing was successful)

or an error occurs (which means that input stream doesn't conform to the grammar).

As there are usually multiple grammar rules to choose from, the information which rule to apply in which situation needs to be encoded somehow and is typically stored in a parsing table. In our case however the grammar is so simple that this would almost be an overkill and so instead the parsing table is represented by some if-statements throughout the code.

The Grammar

Here is the starting point for our grammar:

(1) Exp -> Exp [ + | - | * | / ] Exp

(2) Exp -> ( Exp )

(3) Exp -> num

The grammar is rather self-explanatory.

It is however ambiguous, because it contains a rule of the form NtN.

This means that it is not defined yet whether 2+3*4 should be interpreted

as 2+3=5 followed by 5*4=20 or as 3*4=12 followed by 2+12=14.

By cleverly re-writing the grammar, the operator precedence can be encoded in the grammar.

(1) Exp -> Exp [ + | - ] Exp2

(2) Exp -> Exp2

(3) Exp2 -> Exp2 [ * | / ] Exp3

(4) Exp2 -> Exp3

(5) Exp3 -> ( Exp )

(6) Exp3 -> num

For the previous example 2+3*4 the following derivations would be used from now on:

Exp

(1) Exp + Exp2

(2) Exp2 + Exp2

(4) Exp3 + Exp2

(6) num + Exp2

(3) num + Exp2 * Exp3

(4) num + Exp3 * Exp3

(6) num + num * Exp3

(6) num + num * num

Compare this to the derivation of 3*4+2

Exp

(1) Exp + Exp2

(2) Exp2 + Exp2

(3) Exp2 * Exp3 + Exp2

(4) Exp3 * Exp3 + Exp2

(6) num * Exp3 + Exp2

(6) num * num + Exp2

(4) num * num + Exp3

(6) num * num + num

We see that in both examples the order in which the rules for the operators

+ and * are applied is the same.

It is perhaps slightly confusing that + appears first,

but if you look at the resulting parse tree you can convince yourself that

the result of * flows as an input to + and therefore it needs to be computed first.

Here, I used a left-most derivation of the input stream.

This means that you would always try to replace the left-most symbol next

(which corresponds to the symbol on the top of the stack),

and not something in the middle of your parse tree.

This is what one L in LL(1) actually stands for, so this is also how our parser will operate.

However, there is one more catch.

The grammar we came up with is now non-ambiguous, but still it cannot be parsed by an LL(1) parser,

because multiple rules start with the same non-terminal

and the parser would need to look ahead more than one token to figure out which rule to apply.

Indeed, for the example above you have to look ahead more than one rule

to figure out the derivation yourself.

As the 1 in LL(1) indicates, LL(1)-parsers only look ahead one symbol.

Luckily, one can make the grammar LL(1)-parser-friendly by rewriting all the left recursions

in the grammar rules as right recursions.

(0) S -> Exp $

(1) Exp -> Exp2 Exp'

(2) Exp' -> [ + | - ] Exp2 Exp'

(3) Exp' -> ϵ

(4) Exp2 -> Exp3 Exp2'

(5) Exp2' -> [ * | / ] Exp3 Exp2'

(6) Exp2' -> ϵ

(7) Exp3 -> num

(8) Exp3 -> ( Exp )

Here, ϵ means that the current symbol of the stack should be just popped off,

but not be replaced by anything else.

Also, we added another rule (0) that makes sure

that the parser understands when the input is finished.

Here, $ stands for end of input.

Constructing the parsing table

While we are not going to use an explicit parsing table, we still need to know its contents so that the parser can determine which rule to apply next. To simplify the contents of the parsing table, I will use one little trick that I discovered while implementing the whole thing and that is:

If there is only one grammar rule for a particular non-terminal, just expand it without caring about what is on the input stream.

This is a bit different from what you find in the literature,

where you are instructed to only expand non-terminals if the current terminal permits it.

In our case, this means that the non-terminals S, Exp and Exp2 will be expanded no matter what.

For the other non-terminals, it is quite clear which rule to apply:

+ -> rule (2)

- -> rule (2)

* -> rule (5)

/ -> rule (5)

num -> rule (7)

( -> rule (8)

Note that the rules can only be applied when the current symbol on the stack is fitting to the

left-hand side of the grammar rule.

For example, rule (2) can only be applied if currently Exp' is on the stack.

Since we also have some rules that can be expanded to ϵ,

we need to figure out when that should actually happen.

For this it is necessary to look at what terminal appears after a nullable non-terminal.

The nullable non-terminals in our case are Exp' and Exp2'.

Exp' is followed by ) and $ and Exp2 is followed by +, -, ) and $.

So whenever we encounter ) or $ in the input stream while Exp' is on top of the stack,

we just pop Exp' off and move on.

Implementation notes

A nice thing about LL(1) parsing is that you can just use the call stack for keeping track

of the current non-terminal.

So in the Python implementation, you will find for the non-terminal Exp a function parse_e()

that in turn calls parse_e2(), corresponding to Exp2.

In previous versions of this repository (e.g. commit f1dcad8),

each non-terminal corresponded to exactly one function call.

However, since many of those function calls were just passing variables around,

it seemed to make sense to refactor the code

and now only parse_e(), parse_e2() and parse_e3() are left.

A look at the function parse_e3() shows us how to handle terminals:

def parse_e3(tokens):

if tokens[0].token_type == TokenType.T_NUM:

return tokens.pop(0)

match(tokens, TokenType.T_LPAR)

e_node = parse_e(tokens)

match(tokens, TokenType.T_RPAR)

return e_nodeHere, it is checked whether the current token from the input stream is a number.

If it is, we consume the input token directly without putting it on some intermediate stack.

This corresponds to rule (7).

If it is not a number, it must be a (, so we try to consume this instead

(the function match() raises an exception if the expected and the incoming tokens are different).

Obtaining the Abstract Syntax Tree

The abstract syntax tree (AST) can be constructed on the fly during parsing.

The trick here is to only include those elements that are interesting

(in our case num, +, -, *, / and skip over all the elements that are

only there for grammatical reasons.

One thing you might find worthwile to try is to start with the concrete syntax tree that includes all the elements of the grammar and kick out things that you find are useless. Keeping things visualized definitely helps with this.

Solving Left-Associativity

All of the standard math operators are left-associative,

meaning that 3+2+1 should be interpreted as ((3+2)+1).

For addition, getting this right is not super-crucial, as additions anyway are commutative.

However, once you start playing around with subtractions (or divisions)

this becomes really important as you definitely want 3-2-1 to evaluate to 0

and not to (3-(2-1))=2.

Indeed, this aspect is something that I overlooked in the first version.

Interestingly, in vanilla LL(1) parsing there is no support for left recursion.

As you saw before, we actually had to rewrite all left recursions using right recursions.

However, left-associativity essentially means using left recursions and right-associativity means

using right recursions.

If you just blindly use right recursions like I did,

then suddenly all your operators will be right-associative.

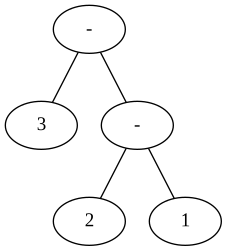

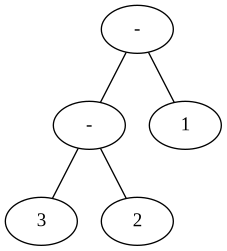

Let's look at two different ASTs for the expression 3-2-1.

This is the default AST, implementing right-associativity.

You can recreate this behaviour and also the picture by going back to commit 14e9b79.

This is the desired AST, implementing left-associativity.

How can we now implement left-associativity?

The key insight here is that something needs to be done whenever you have two or more

operators of the same precedence level in a row.

So whenever we parse a - or + operation and the next token to be processed is also

either - or +, then we should actually be using left recursion.

This requires us to step outside of the LL(1) paradigm for a moment and piece together the

relevant subtree differently, for example like so:

def parse_e(tokens):

left_node = parse_e2(tokens)

while tokens[0].token_type in [TokenType.T_PLUS, TokenType.T_MINUS]:

node = tokens.pop(0)

node.children.append(left_node)

node.children.append(parse_e2(tokens))

left_node = node

return left_nodeThe same is done in parse_e2() for getting the associativity of multiplication and division right.