- Change Control (add/restore)

- Version Control (Commits)

- Collaboration (parallel development)

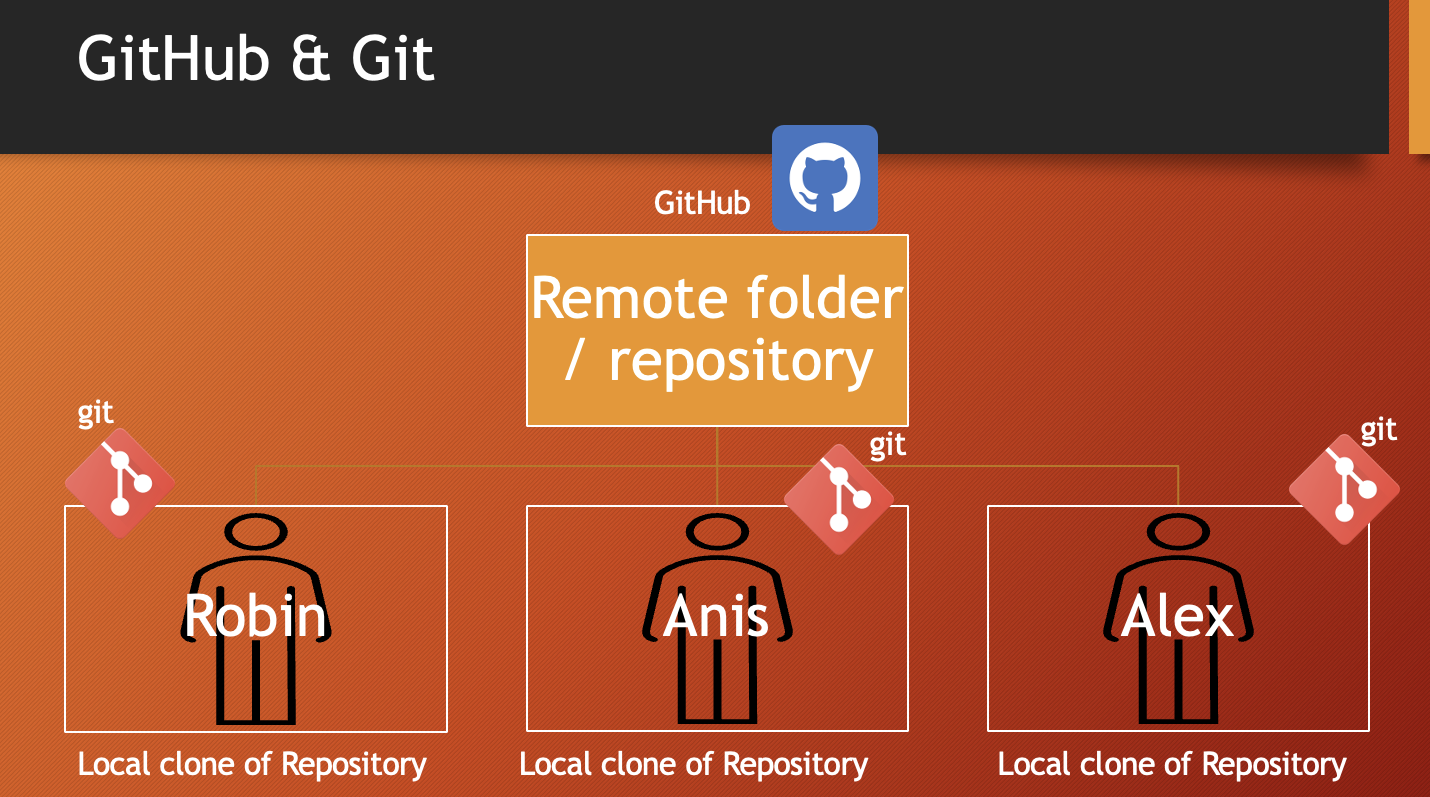

- git is a version control software

- It keep track of code changes

- It helps to collaborate in a project

- It is installed and maintained locally

- It provides Command Line Interface (CLI)

- Released in April 7, 2005

- Developed by Linus Torvalds & Junio C Hamano

- GitHub is a hosting service where we can keep our git repositiory/folders

- It is maintained on cloud/web

- It provides Graphical User Interface (GUI)

- Founded in 2008

- go to this site and register with a valid email address.

- Download and install git on your pc: https://git-scm.com/

- check git version: open terminal or cmd then use the command

git --versionto find out whether git is installed or not. if git is installed it will return a version number of git.

git commandName -help

-

directoy/folder

-

dir/ls/ls – List directory contents.

-

cd – Change directory.

-

cd/Get-Location/pwdShow current directory

-

mkdir – Create a new directory. Example: mkdir directory

-

rmdir/Remove-Item/rm – Remove a directory.

Example:

rmdir /S /Q directory

Remove-Item -Recurse directory

rm -r directory

-

-

File

-

copy/New-Item/touch- Create file. Example: copy nul filename.txt / New-Item -ItemType File -Name "filename.txt" / touch filename.txt

-

echo Your content here > filename.txt / "Your content here" | Out-File -FilePath "filename.txt" / echo Your content here > filename.txt - Writing in a file.

- in mac

cat > filename.txt Your content here Another line of content Ctrl + D or printf "Your content here\n" > filename.txt to append printf "Additional content\n" >> filename.txt

-

type/Get-Content/cat - View file contents. Example: type file / Get-Content file / cat file

-

copy/Copy-Item/cp – Copy files. Example: copy source destination / Copy-Item source destination/cp source destination

-

del/Remove-Item/rm– Delete files. Example: del file / Remove-Item file / rm file

-

-

cls/Clear-Host/clear – Clear the screen.

-

echo – Display a message or turn command echoing on or off. Example: echo text / Write-Output text / echo text

run the following command in your terminal:

git config --global core.editor "code --wait"

Now when you run git commit or git -config --global -e it will open the Git editor within a file in VS Code.

Git configuration is an important part of setting up and managing your Git environment. Configuration settings in Git can be set at three different levels: local, global, and system.

- Local configuration applies only to a specific repository.

- Global configuration applies to the user across all repositories on the system.

- System configuration applies to all users on the system (rarely used).

To view configuration settings:

git config --list

git config --local --list (view local configuration settings)

git config --global --list (view global configuration settings

git config --system --list (view system configuration settings)If you want to remove a specific configuration setting in Git, such as a user name set with git config, you can use the git config --unset command. Here’s how to remove a configuration setting:

cd /path/to/your/repository

git config --local --unset user.name

git config --global --unset user.name

sudo git config --system --unset user.nameLocal configuration settings are stored in the .git/config file within a specific repository. Use .git/config commad to see what you have inside the file.

To set local configuration options:

cd /path/to/your/repository

git config --local user.name "Your Name"

git config --local user.email "your.email@example.com"Global configuration settings are stored in the ~/.gitconfig file (or ~/.config/git/config depending on the system). Use open ~/.gitconfig commad to see what you have inside the file.

To set global configuration options:

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"System configuration settings are stored in the /etc/gitconfig file.

To set system configuration options (requires administrative privileges):

sudo git config --system core.editor "nano"To set system configuration to default:

sudo git config --system core.editor "code --wait"Here are some commonly used Git configuration options:

-

User Information

- Set the name and email address that will be used for your commits.

git config --global user.name "Your Name" git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

-

Default Editor

- Set the default text editor for Git.

git config --global core.editor "nano" # or "vim", "code --wait" (default), etc.

-

Line Endings

- Configure how Git handles line endings between different operating systems.

git config --global core.autocrlf input # Use "true" on Windows, "input" on macOS/Linux -

Merge Tool

- Set the default merge tool for resolving conflicts.

git config --global merge.tool "meld" -

Diff Tool

- Set the default diff tool for viewing differences.

git config --global diff.tool "meld" -

Aliases

- Create shortcuts for commonly used Git commands.

git config --global alias.co "checkout" git config --global alias.br "branch" git config --global alias.ci "commit" git config --global alias.st "status"

You can also directly view and edit the configuration files if needed:

-

Global configuration file:

nano ~/.gitconfig -

Local configuration file:

nano .git/config

-

System configuration file (requires administrative privileges):

sudo nano /etc/gitconfig

Here is an example of what a typical global configuration file (~/.gitconfig) might look like:

[user]

name = Your Name

email = your.email@example.com

[core]

editor = nano

autocrlf = input

[merge]

tool = meld

[diff]

tool = meld

[alias]

co = checkout

br = branch

ci = commit

st = statusBy configuring Git at the local and global levels, you can customize your Git environment to suit your preferences and workflow. Local configuration settings are specific to individual repositories, while global settings apply across all repositories for a user. Understanding and managing these settings will help you streamline your Git operations and improve your productivity.

-

SSH, or Secure Shell, is a cryptographic network protocol used for secure communication between devices over an unsecured network. It provides a secure way to access remote systems, execute commands, transfer files, and manage network infrastructure.

-

SSH allows users to securely log into remote systems and execute commands as if they were sitting in front of the machine.

-

go to your github account

-

- type in terminal

for generating SSH Key: ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your email goes here" - type in terminal

cat ~/.ssh/id_ed255519.pub - copy the ssh and add to github

- type in terminal

The command ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your email goes here" is used to generate a new SSH key pair (a public and private key) for secure authentication. Here’s a detailed breakdown of the command:

-

ssh-keygen:- This is the command-line tool used to generate, manage, and convert authentication keys for SSH.

-

-t ed25519:- The

-toption specifies the type of key to create. ed25519refers to the Ed25519 algorithm, which is a modern and secure elliptic-curve algorithm for SSH keys. It is known for its high security, performance, and small key size compared to older algorithms like RSA.

- The

-

-C "your email goes here":- The

-Coption adds a comment to the key. This comment is typically used to identify the key. "your email goes here"is the comment that will be added to the key. It's common to use your email address here, so you can easily identify the key later.

- The

-

Prompt for a File Location:

- After running the command, you will be prompted to specify a file to save the key. By default, it will suggest a location such as

~/.ssh/id_ed25519. - If you press Enter without specifying a location, it will use the default path.

- After running the command, you will be prompted to specify a file to save the key. By default, it will suggest a location such as

-

Prompt for a Passphrase:

- You will be asked to enter a passphrase. This is an optional step, but adding a passphrase provides an additional layer of security. If you choose to set a passphrase, you’ll need to enter it whenever you use the private key.

- If you do not want to set a passphrase, you can press Enter without typing anything.

-

Key Generation:

- The tool generates a new Ed25519 key pair and saves it to the specified file. The private key is stored in the file you specified (e.g.,

~/.ssh/id_ed25519), and the public key is stored in a file with the same name but with a.pubextension (e.g.,~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub).

- The tool generates a new Ed25519 key pair and saves it to the specified file. The private key is stored in the file you specified (e.g.,

When you run the command, the interaction might look like this:

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your_email@example.com"

Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/home/yourusername/.ssh/id_ed25519):

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Enter same passphrase again:

Your identification has been saved in /home/yourusername/.ssh/id_ed25519.

Your public key has been saved in /home/yourusername/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub.

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:examplefingerprint your_email@example.com

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ED25519 256]--+

| ..o. |

| .+ + |

| . o* . |

| o.O |

| .=S o |

| . + . = . |

| + o + . o |

| + o + . |

| o o.. |

+----[SHA256]-----+-

Add the Public Key to the Remote Server:

-

Copy the contents of the public key file (e.g.,

~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub) to the~/.ssh/authorized_keysfile on the remote server you want to access. -

You can use the

ssh-copy-idcommand for this:ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub user@remote_host

-

-

Connect Using SSH:

-

Use the SSH command to connect to the remote server. SSH will use your private key for authentication.

ssh user@remote_host

-

- Repositories

- Staging Area

- Working Directory

- Local Repositories

- Remote Repositories

- Commits

- Branches

- Merging

-

creating a git folder

-

ls -a : list all files inside of a directory

mkdir DIRECTORY_NAME_HERE cd DIRECTORY_NAME_HERE git init Example: mkdir notes cd notes git init ls -a

-

-

adding new files in git folder

-

git status : displays the state of the working directory and staging area

ls -a touch fileName.extension open fileName.extension git status Example: touch day1.txt open day1.txt write something inside the file

-

-

Git is aware of the file but not added to our git repo

-

Files in git repo can have 2 states – tracked (git knows and added to git repo), untracked (file in the working directory, but not added to the local repository)

-

To make the file trackable stagging or adding is required

-

Adding files to stagging area:

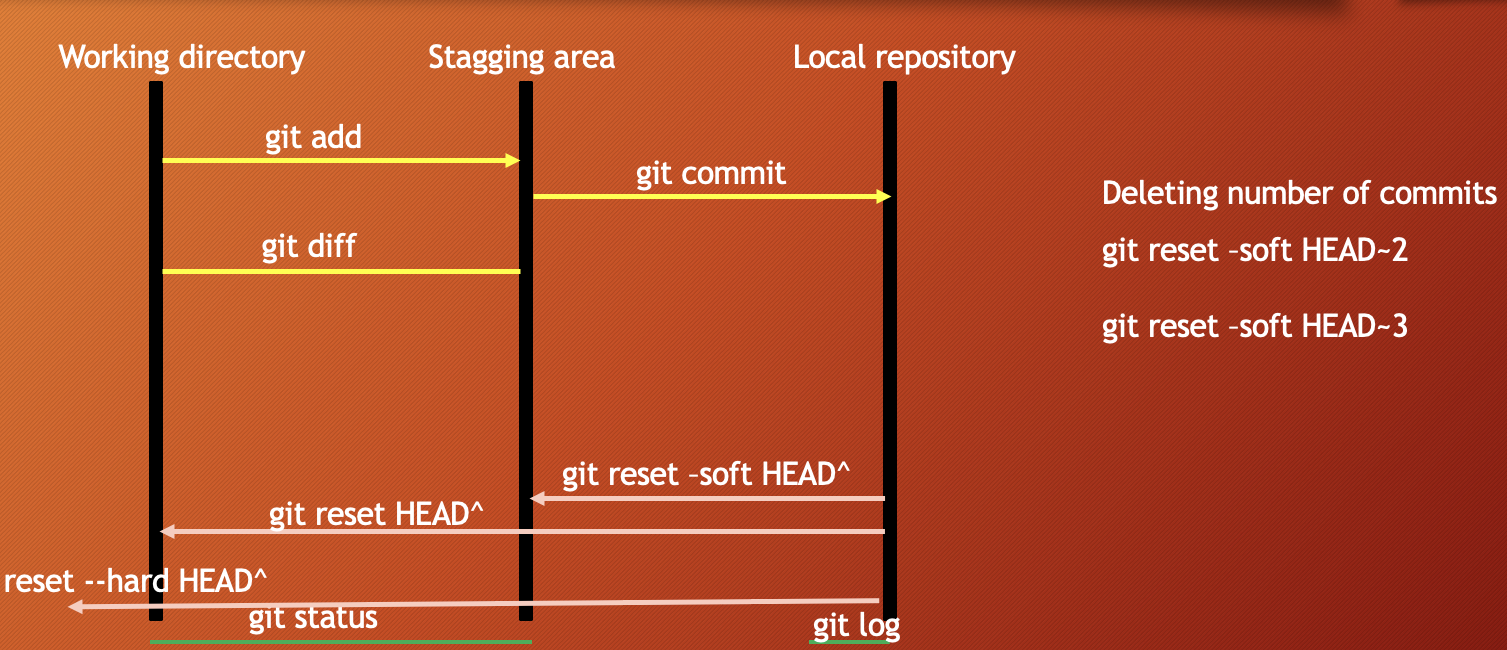

git add fileNameadd a file in staging area / indexgit add .add all files of directory to stagging area not subdirectorygit add -Aadd all files of directory and subdirectory to stagging areagit rm --cached fileNameunstage a file from staging areagit diff- checking the differences of a staged filegit restore fileName- restore the file

git commit -m "message"move the file to local repository from stagging areagit logcheck the commit historygit reset --soft HEAD^uncommit the commit in HEAD and move to staging areagit reset HEAD^uncommit the commit in HEAD and move to unstaging / working areagit reset --hard HEAD^uncommit the commit in HEAD and delete the commit completely with all the changes

Making effective commits is essential for maintaining a clean, understandable project history. Here are some best practices to follow:

-

Subject Line: A short summary of the changes (50 characters or less).

-

Body (optional): A detailed explanation of the changes, if necessary (72 characters per line).

-

Use the Imperative Mood in Commit Messages: Prefix your commit messages with imperative commands such as: fix, refactor, add, and remove. Write commit messages as if you are giving an order. For example, use "Add feature" instead of "Added feature".

-

git commit -m "Add user login feature" -m " - Implement login endpoint" -m " - Validate user credentials" -m " - Return JWT token on successful login"- -m "Add user login feature": This is your commit message, a concise summary of the changes. - -m " - Implement login endpoint", -m " - Validate user credentials", -m " - Return JWT token on successful login": These are the lines of your detailed description, each prefixed with a dash and a space for proper formatting. - output:```txt Add user login feature - Implement login endpoint - Validate user credentials - Return JWT token on successful login ```

- Each commit should represent a single, logical change. Avoid bundling unrelated changes in a single commit.

- Commit frequently to save your work and document your progress. However, avoid making trivial commits that do not add value.

-

If your commit relates to an issue or pull request, reference it in the commit message.

-

Example:

Fix user login validation bug Closes #123

- Ensure your code works and passes all tests before making a commit. This helps maintain the integrity of the codebase.

- Do not commit files that are generated by the build process or your development environment (e.g.,

node_modules,dist,.logfiles). Use.gitignoreto exclude these files.

-

For security and authenticity, consider signing your commits using GPG.

-

Example:

git commit -S -m "Your commit message"

Add user authentication

- Implement JWT-based authentication

- Add login endpoint

- Validate user credentials

- Return JWT token on successful login

Closes #45-

Committing Changes:

git add . git commit -m "Clear and concise commit message"

-

Staging Changes Selectively:

git add -p

-

Amending the Last Commit:

git commit --amend -m "Updated commit message" -

Viewing Commit History:

git log

-

Viewing a Specific Commit:

git show <commit-hash>

-

Rebasing to Edit Commits:

git rebase -i HEAD~3

By following these best practices, you ensure that your commit history is clean, meaningful, and easy to navigate, which greatly improves the collaborative experience and project maintainability.

- git init: Initialize a new Git repository.

- git clone: Clone an existing repository.

- git status: Check the status of your repository.

- git add: Add files to the staging area.

- git commit: Commit changes to the repository.

- git log: View commit history.

- create a .gitignore file and add the things you do not want to add in the stagging area

- Inside .gitignore we can keep secret files, hidden files, temporary files, log files

secret.txtsecret.txt will be ignored*.txtignore all files with .txt extension!main.txtignore all files with .txt extension without .main.txttest?.txtignore all files like test1.txt test2.txttemp/all the files in temp folders will be ignored

The git rm command is used to remove files from the working directory and the staging area (index). This command is helpful when you need to delete a file and have that deletion tracked by Git so that the file is removed in future commits.

-

Remove a File and Stage the Deletion:

git rm <file>

This command removes the specified file from the working directory and stages the removal for the next commit.

-

Remove a File from Only the Staging Area:

git rm --cached <file>

This command removes the specified file from the staging area, but leaves the file in the working directory. This is useful if you want to stop tracking the file but not delete it from your filesystem.

-

Remove a File and Force the Deletion:

git rm -f <file>

This command forces the removal of the file from both the working directory and the staging area, even if the file has changes that haven't been committed.

-

Remove a Directory Recursively:

git rm -r <directory>

This command removes the specified directory and all of its contents (files and subdirectories) recursively.

-

Create a File:

echo "Hello World" > hello.txt git add hello.txt git commit -m "Add hello.txt"

-

Remove the File:

git rm hello.txt git commit -m "Remove hello.txt"This sequence of commands creates a file, stages and commits it, then removes the file and stages the removal for the next commit.

-

Create a File:

echo "Temporary data" > temp.txt git add temp.txt git commit -m "Add temp.txt"

-

Stop Tracking the File:

git rm --cached temp.txt git commit -m "Stop tracking temp.txt"This sequence of commands creates a file, stages and commits it, then stops tracking the file in the repository but keeps it in the working directory.

-

Modify a File:

echo "New content" >> existing.txt

-

Force Remove the Modified File:

git rm -f existing.txt git commit -m "Force remove existing.txt"This sequence of commands modifies a file, then forcefully removes it and stages the removal for the next commit, ignoring any uncommitted changes.

- Safety:

git rmis a safe way to delete files because it ensures that the deletion is tracked by Git, preventing future confusion about missing files. - Untracked Files: If a file is untracked (not staged or committed),

git rmwill not remove it. You can use regular shell commands to delete untracked files. - Removing Directories: When removing directories, the

-r(recursive) option is required to delete all contents within the directory.

The git rm command is essential for managing file deletions in a Git repository. It ensures that file removals are tracked and can be committed, providing a clear history of changes within the project.

- Creating a GitHub account

- Creating a new repository

- creating a readme.md

- Forking a repository

- Cloning a repository from GitHub

- Basic GitHub web interface overview

- Connecting local and remote repo

- Push and pull

- Pull Requests

- Issues

- Basic repository settings

- sign in to your github account

- create a git repo

- check remote connection:

git remoteorgit remote -v git remote add name <REMOTE_URL>example: git remote add origin http://...- to clone a remote repository:

git clone <REMOTE_URL>

- push a branch

git push -u origin branch_name - push all branches

git push --all - pull from a repo:

git pullwhich is equivalent to git fetch + git merge

Working with remotes in Git involves interacting with repositories hosted on a remote server. These remote repositories can be on platforms like GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, or your own server. Here are key concepts and commands for working with remotes:

- Remote Repository: A repository hosted on a server, which can be accessed via URLs (HTTPS, SSH).

- Origin: The default name given to the remote repository from which you cloned your local repository.

- Fetch: Download commits, files, and references from a remote repository into your local repository.

- Pull: Fetch changes from a remote repository and immediately merge them into your local branch.

- Push: Upload your local commits to a remote repository.

- Remote Branches: Branches in a remote repository that your local repository is aware of.

To add a new remote repository, use the git remote add command:

git remote add <name> <url>Example:

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/your-repo.gitTo view the remotes you have set up:

git remote -vThis command will list the short names (like origin) and the URLs of the remote repositories.

To fetch changes from the remote repository without merging them into your local branch:

git fetch <remote>Example:

git fetch originTo fetch and merge changes from the remote repository into your current branch:

git pull <remote> <branch>Example:

git pull origin mainTo push your local commits to a remote repository:

git push <remote> <branch>Example:

git push origin mainTo rename a remote:

git remote rename <old-name> <new-name>Example:

git remote rename origin upstreamTo remove a remote:

git remote remove <name>Example:

git remote remove originTo view detailed information about a remote:

git remote show <name>Example:

git remote show originWhen you clone a repository, Git automatically adds the remote for you, named origin.

git clone https://github.com/yourusername/your-repo.gitIf you want to add another remote, for example, to contribute to another repository:

git remote add upstream https://github.com/anotheruser/another-repo.gitTo fetch changes from the upstream remote:

git fetch upstreamAfter fetching changes, you can merge them into your current branch:

git merge upstream/mainIf you pull changes and there are conflicts, Git will prompt you to resolve them manually. After resolving conflicts:

-

Stage the resolved files:

git add <resolved-file>

-

Continue the merge or pull process:

git commit

After making commits locally, push them to the origin remote:

git push origin main- Regularly Fetch and Pull: Keep your local repository up-to-date by regularly fetching and pulling changes from the remote repository.

- Push Often: Push your changes frequently to share your progress and avoid large merges.

- Use Branches: Work on feature branches and push them to the remote repository to keep the

mainbranch stable and clean. - Collaborate with Pull Requests: Use pull requests to review and discuss changes before merging them into the main branch.

Working with remotes is an essential part of collaborating with others in Git. By understanding and using these commands effectively, you can manage and integrate changes smoothly in your projects.

- Everything you need to know about README.md is discussed in the video.

- 6 heading levels: number of hashes define heading levels. check the following examples:

# heading 1 level text is here## heading 2 level text is here

- bold syntax:

**text goes here** - italic syntax:

_text goes here_ - bold and italic syntax:

**_text goes here_** - strikethrouh syntax:

~~this is~~ - single line code syntax: `` place code inside backticks

- multiple line code syntax: ``` place code inside three open and closing backticks

- multiple line code syntax language specific: ```html for specific lanaguage use language name when starting; not closing

- Ordered List syntax

1. HTML

2. CSS

1. Fundamental

2. CSS Architecture - BEM

3. CSS Preprocessor - SASS

3. JS-

Unordered List syntax ->

- html - css - Fundamental - CSS Architecture - BEM - CSS Preprocessor - SASS - js

-

Task List

- [x] Task1 - [x] Task2 - [x] Task3

-

adding link

<!-- automatic link --> http://www.studywithanis.com <!-- markdown link syntax --> [title](link) [studywithanis](http://www.studywithanis.com) [studywithanis][websitelink] <!-- all link is here --> [websitelink]: http://www.studywithanis.com

-

adding image syntax ->

-

adding emoji

emoji src ### Smileys 😀 😃 😄 😁 😆 😅 😂 🤣 🥲☺️ 😊 😇 🙂 🙃 😉 😌 😍 🥰 😘 😗 😙 😚 😋 😛 😝 😜 🤪 🤨 🧐 🤓 😎 🥸 🤩 🥳 😏 😒 😞 😔 😟 😕 🙁☹️ 😣 😖 😫 😩 🥺 😢 😭 😤 😠 😡 🤬 🤯 😳 🥵 🥶 😱 😨 😰 😥 😓 🤗 🤔 🤭 🤫 🤥 😶 😐 😑 😬 🙄 😯 😦 😧 😮 😲 🥱 😴 🤤 😪 😵 🤐 🥴 🤢 🤮 🤧 😷 🤒 🤕 🤑 🤠 😈 👿 👹 👺 🤡 💩 👻 💀 ☠️ 👽 👾 🤖 🎃 😺 😸 😹 😻 😼 😽 🙀 😿 😾- Gestures and Body Parts 👋 🤚 🖐 ✋ 🖖 👌 🤌 🤏 ✌️ 🤞 🤟 🤘 🤙 👈 👉 👆 🖕 👇 ☝️ 👍 👎 ✊ 👊 🤛 🤜 👏 🙌 👐 🤲 🤝 🙏 ✍️ 💅 🤳 💪 🦾 🦵 🦿 🦶 👣 👂 🦻 👃 🫀 🫁 🧠 🦷 🦴 👀 👁 👅 👄 💋 🩸

-

adding table

table syntax

| heading1 | heading2 |

| ----- | ----- |

| data1 | data2 |

| data3 | data4 |

| data5 | data6 |GitHub Issues is a feature within GitHub that allows users to track and manage work on a project. It's a powerful tool for managing bugs, tasks, feature requests, and other project-related activities. Here's a detailed explanation of GitHub Issues:

GitHub Issues provides a way to:

- Report bugs

- Suggest enhancements

- Ask questions

- Manage tasks

- Track project milestones

Each issue serves as a discussion thread where collaborators can comment, provide feedback, and attach files or code snippets.

-

Creating Issues

- Users can create an issue by clicking on the "Issues" tab in a repository and then selecting "New issue."

- Each issue requires a title and description. The description can include text, markdown, images, and code snippets.

-

Labels

- Labels are used to categorize issues. For example, labels can indicate the type of issue (bug, enhancement, question) or its priority.

- Custom labels can be created to suit the project's needs.

-

Assignees

- Issues can be assigned to one or more collaborators who are responsible for resolving the issue.

-

Milestones

- Milestones group issues into larger goals or releases. This helps in tracking progress toward significant project objectives.

-

Projects

- GitHub Projects is a feature that allows users to organize issues into boards, similar to Kanban boards, for better project management.

-

Comments and Mentions

- Collaborators can comment on issues to provide updates, feedback, or solutions.

- Users can mention others using

@usernameto draw their attention to specific comments or issues.

-

References and Links

- Issues can be cross-referenced with other issues, pull requests, and commits using their respective IDs (e.g.,

#123for issue 123).

- Issues can be cross-referenced with other issues, pull requests, and commits using their respective IDs (e.g.,

-

Closing Issues

- Issues can be closed manually by maintainers or automatically when a related pull request is merged using keywords like "fixes #123" in commit messages.

-

Templates

- Repository maintainers can create issue templates to guide users in providing necessary information when opening new issues.

-

Opening an Issue

- A user opens an issue describing a bug, feature request, or task.

- Labels and milestones can be assigned at this stage.

-

Discussion

- Collaborators discuss the issue in the comments, providing insights, feedback, and potential solutions.

- The issue can be updated based on the discussion.

-

Assigning and Prioritizing

- The issue is assigned to one or more developers.

- The priority is set using labels or by placing the issue within a milestone.

-

Working on the Issue

- Developers work on the issue, often linking commits and pull requests to the issue for tracking progress.

-

Closing the Issue

- Once the issue is resolved, it is closed manually or automatically via a merged pull request.

-

Reviewing Closed Issues

- Closed issues can be reviewed for historical reference and to ensure that similar issues do not arise again.

- Centralized Tracking: All issues related to a project are tracked in one place.

- Collaborative Problem-Solving: Issues facilitate discussion and collaboration among team members.

- Transparency: The status and progress of issues are visible to all project collaborators.

- Efficient Workflow: Issues integrate seamlessly with other GitHub features like pull requests and project boards, making it easier to manage the development lifecycle.

- Use Descriptive Titles and Descriptions: Ensure issues are clear and concise.

- Label Appropriately: Use labels to categorize and prioritize issues.

- Stay Organized: Regularly review and update issues, milestones, and projects.

- Encourage Participation: Invite team members to comment, contribute, and collaborate on issues.

- Close Issues Promptly: Close resolved issues to keep the repository clean and up-to-date.

GitHub Issues is a versatile tool that enhances project management and collaboration, making it easier to track, discuss, and resolve tasks and bugs in software development projects.

Undo: git revert, git checkout, git reset, git clean, git rm Undoing changes in Git can be done in several ways, depending on what you need to achieve. Here are some common scenarios and the Git commands you can use to undo changes:

git reset --soft <commitId> (commit to stagging)

git reset <commitId> (commit to unstaged)

git reset --hard <commitId> (commit to discard from working directory)If you have modified files but haven't staged them yet and want to discard these changes:

git checkout -- <file>To discard changes in all files:

git checkout -- .If you have staged changes but haven't committed them yet and want to unstage them:

git reset HEAD <file>To unstage all changes:

git reset HEAD .If you want to discard all local changes, both staged and unstaged:

git reset --hard HEADIf you want to change the most recent commit (e.g., to add a missing file or correct a commit message):

git commit --amendIf you want to undo a specific commit but keep the history (create a new commit that reverses the changes):

git revert <commit>If you want to move the branch pointer to a previous commit, effectively discarding all commits that came after:

git reset --hard <commit>For example, to reset to the commit abcd1234:

git reset --hard abcd1234To undo a commit that has already been pushed to a shared repository without rewriting history:

git revert <commit>

git pushTo forcefully rewrite the history of a branch that has already been pushed (use with caution):

git reset --hard <commit>

git push --force- Modify a file (

example.txt).

echo "some changes" > example.txt- Discard the changes.

git checkout -- example.txt- Stage a file.

git add example.txt- Unstage the file.

git reset HEAD example.txt- Make a commit.

git commit -m "Initial commit"- Amend the commit to include a missed file.

echo "missed content" > missed.txt

git add missed.txt

git commit --amend- Make a commit.

echo "bad change" > bad.txt

git add bad.txt

git commit -m "Bad commit"- Revert the commit.

git revert HEAD- Make a series of commits.

echo "commit 1" > file1.txt

git add file1.txt

git commit -m "Commit 1"

echo "commit 2" > file2.txt

git add file2.txt

git commit -m "Commit 2"

echo "commit 3" > file3.txt

git add file3.txt

git commit -m "Commit 3"- Reset to the first commit.

git reset --hard HEAD~2 or git reset --hard <commitId>These commands provide powerful ways to undo changes in Git, but they should be used carefully, especially when working with shared repositories, to avoid disrupting other collaborators.

-

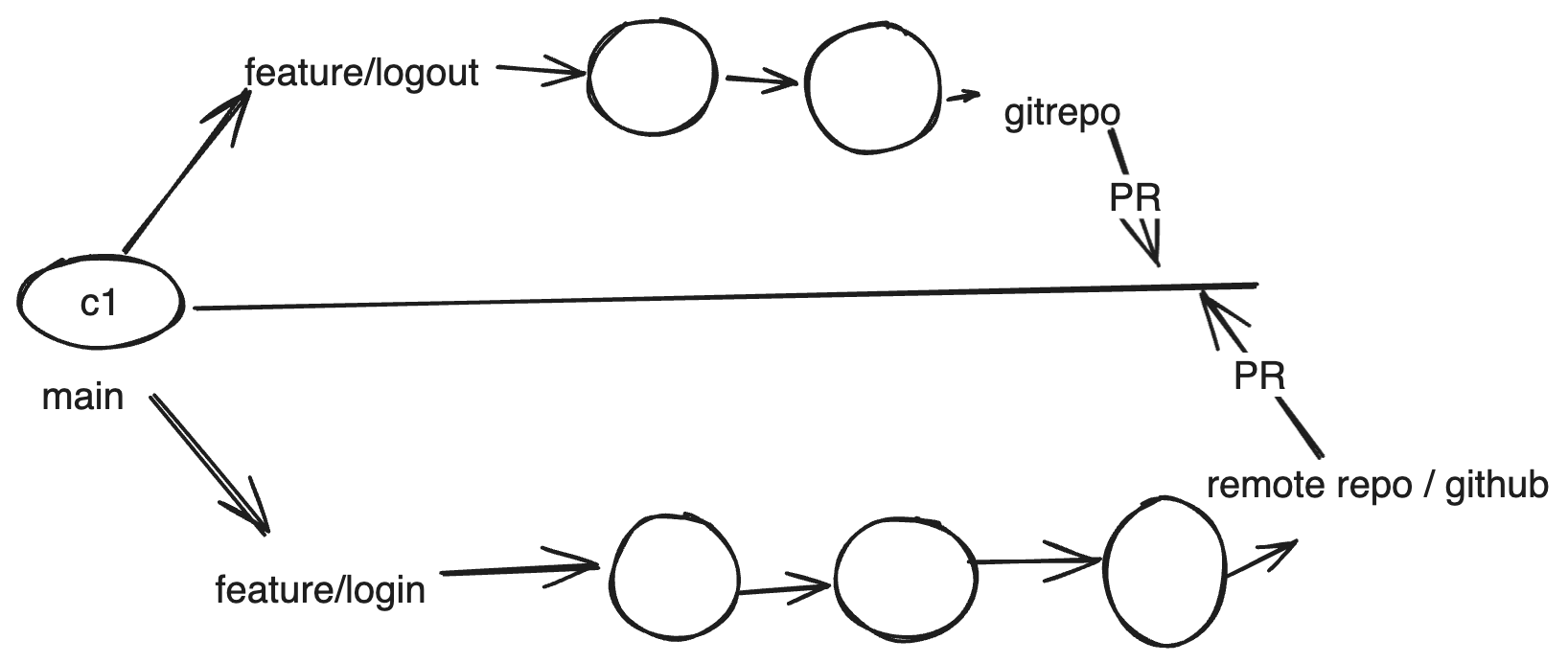

Branch is a new and separate branch of the master/main repository, which allows you parallel development.

-

Branching allows you to diverge from the main line of development and continue working on a separate line of code without affecting the main codebase. When you create a branch, you essentially create a copy of the code at a certain point in time, and you can make changes to this copy independently of other branches. Branches are often used for developing new features, fixing bugs, or experimenting with changes.

-

Merging is the process of combining the changes from one branch (the source branch) into another (the target branch). This allows you to incorporate the changes made in one branch back into the main codebase or another branch. When you merge branches, Git automatically integrates the changes, resolving any conflicts that may arise if the same part of the code was modified in both branches.

-

create a branch

git branch branch_name -

List branches

git branch -

List all remote branches

git branch -r -

List all local & remote branches

git branch -a -

move to a branch

git checkout branch_name -

create and move to a branch

git checkout -b branch_name -

delete a branch:

git branch -d branch_name -

merge branches:

git checkout branchName git merge branchName

-

git log --oneline --all --graph

- Reeference:

When working on a feature such as a navbar for a website using Git, it's important to follow a structured workflow to ensure that your changes are organized, traceable, and integrated smoothly into the main project. Here's a typical working process you can follow:

- Working Process on Git for a Navbar Feature

Ensure that you have a local copy of the repository and are on the latest version of the main branch.

# Clone the repository if you haven't already

git clone https://github.com/yourusername/yourrepository.git

# Navigate into the project directory

cd yourrepository

# Fetch the latest changes from the remote repository

git fetch origin

# Checkout the main branch

git checkout main

# Pull the latest changes

git pull origin mainCreate a new branch specifically for the navbar feature. This keeps your work isolated and makes it easier to manage changes.

# Create and switch to a new branch for the navbar feature

git checkout -b feature/navbarWork on the navbar feature in your local environment. Make sure to commit your changes incrementally with clear and descriptive messages.

# Stage changes for the navbar HTML structure

git add index.html

git commit -m "Add basic HTML structure for the navbar"

# Stage changes for the navbar styling

git add styles/navbar.css

git commit -m "Add CSS styling for the navbar"

# Stage changes for the navbar JavaScript

git add scripts/navbar.js

git commit -m "Add JavaScript functionality for the navbar"To avoid conflicts and keep your branch up to date with the main branch, regularly fetch and merge changes from the main branch.

# Fetch the latest changes from the remote repository

git fetch origin

# Switch to the main branch

git checkout main

# Pull the latest changes

git pull origin main

# Switch back to your feature branch

git checkout feature/navbar

# Merge the latest changes from the main branch into your feature branch

git merge mainThoroughly test the navbar feature in your local environment to ensure it works as expected and does not introduce any bugs.

Once you are satisfied with your changes, push your feature branch to the remote repository.

# Push your feature branch to the remote repository

git push origin feature/navbarOpen a pull request on the remote repository to merge your feature branch into the main branch. Provide a clear description of the changes and any related information.

- Go to your repository on GitHub (or your Git hosting service).

- Click on the "Pull Requests" tab.

- Click on "New Pull Request".

- Select

feature/navbaras the

Suppose you're working on a branch called feature-branch and you made a commit that introduced a bug. You realize the mistake after pushing the branch to the remote repository, but before creating the PR. You want to revert that commit before proceeding with the PR.

- Step-by-Step Example

-

Check the Commit History First, identify the commit you want to revert by checking the commit history.

git log --oneline

Let's say the commit history looks like this:

e5d2c3f Bug fix for incorrect calculation b3d9a7e Implement new feature 7a8b9d1 Initial commitHere,

e5d2c3fis the commit that introduced the bug. -

Revert the Commit Use

git revertto create a new commit that undoes the changes from the faulty commit.git revert e5d2c3f

This command will open your default editor to allow you to write a commit message for the revert. By default, the message will be something like "Revert 'Bug fix for incorrect calculation'". Save and close the editor.

-

Push the Reverted Commit Now, push the changes to the remote repository.

git push origin feature-branch

Your commit history will now look like this:

2f3a4b6 Revert "Bug fix for incorrect calculation" e5d2c3f Bug fix for incorrect calculation b3d9a7e Implement new feature 7a8b9d1 Initial commitThe commit

2f3a4b6undoes the changes made ine5d2c3f. -

Create the Pull Request After pushing, you can create a PR as usual. The PR will include the revert commit, which will effectively undo the faulty changes in the codebase when merged.

- Safety: If your branch is already pushed to the remote repository,

git revertis safe because it doesn't rewrite history. - Clarity: The revert commit clearly documents that a specific change was undone, making the history easier to understand for others reviewing the PR.

- Traceability: Future developers can see both the original change and its reversal, along with the reasons if described in the commit message. This helps maintain a clear and accurate project history.

This approach ensures that your branch is clean and ready for review in the PR without the risk of disrupting the commit history for other contributors.

If the Pull Request (PR) has already been merged and you realize that there was a mistake, you can still undo the changes, but the approach differs slightly. Here’s how to handle it using git revert:

Your PR has been merged into the main branch (or any other target branch). Now you realize that the changes introduced by your PR need to be undone.

-

Identify the Merge Commit When a PR is merged, it creates a merge commit. You need to identify this merge commit in the

mainbranch.git log --oneline --graph

You’ll see something like this:

* 9fceb02 Merge pull request #42 from feature-branch |\ | * 1a2b3c4 Implement new feature | * 5d6f7g8 Fix bug in calculation |/ * e3c9d12 Previous commit on mainHere,

9fceb02is the merge commit for the PR. -

Revert the Merge Commit To undo the changes introduced by the PR, use

git revertwith the-m 1option. The-m 1indicates that you want to revert the changes from the first parent of the merge commit (usually the main branch before the PR was merged).git revert -m 1 9fceb02

This will create a new commit that reverses all the changes introduced by the PR.

-

Push the Revert Commit Push the new commit to the

mainbranch:git push origin main

Now the history will look something like this:

* abcd123 Revert "Merge pull request #42 from feature-branch" * 9fceb02 Merge pull request #42 from feature-branch |\ | * 1a2b3c4 Implement new feature | * 5d6f7g8 Fix bug in calculation |/ * e3c9d12 Previous commit on mainThe

abcd123commit effectively undoes the changes introduced by the PR while keeping the commit history intact. -

Communicate the Revert It’s good practice to communicate with your team or document the reason for the revert in the commit message and any relevant issue trackers. This ensures everyone is aware of the change and understands why the revert was necessary.

- History Preservation:

git revertpreserves the commit history, which is crucial in a shared repository. This way, all changes are documented, including mistakes and their reversals. - Avoids Conflicts:

git revertcreates a new commit that undoes the changes, which is less likely to cause conflicts with other ongoing work compared to usinggit reset. - Transparency: The revert commit makes it clear to everyone in the project that the changes from the PR were undone for a specific reason.

- Re-apply Changes in a New PR: If you want to make corrections rather than completely undoing the changes, you could create a new branch, apply the necessary fixes, and open a new PR.

- Hotfix Branch: If the issue is critical, you might create a hotfix branch to address it quickly and then merge that branch back into

main.

By reverting the merge commit, you ensure that the problematic changes are undone while maintaining a clear and accurate history in your Git repository.

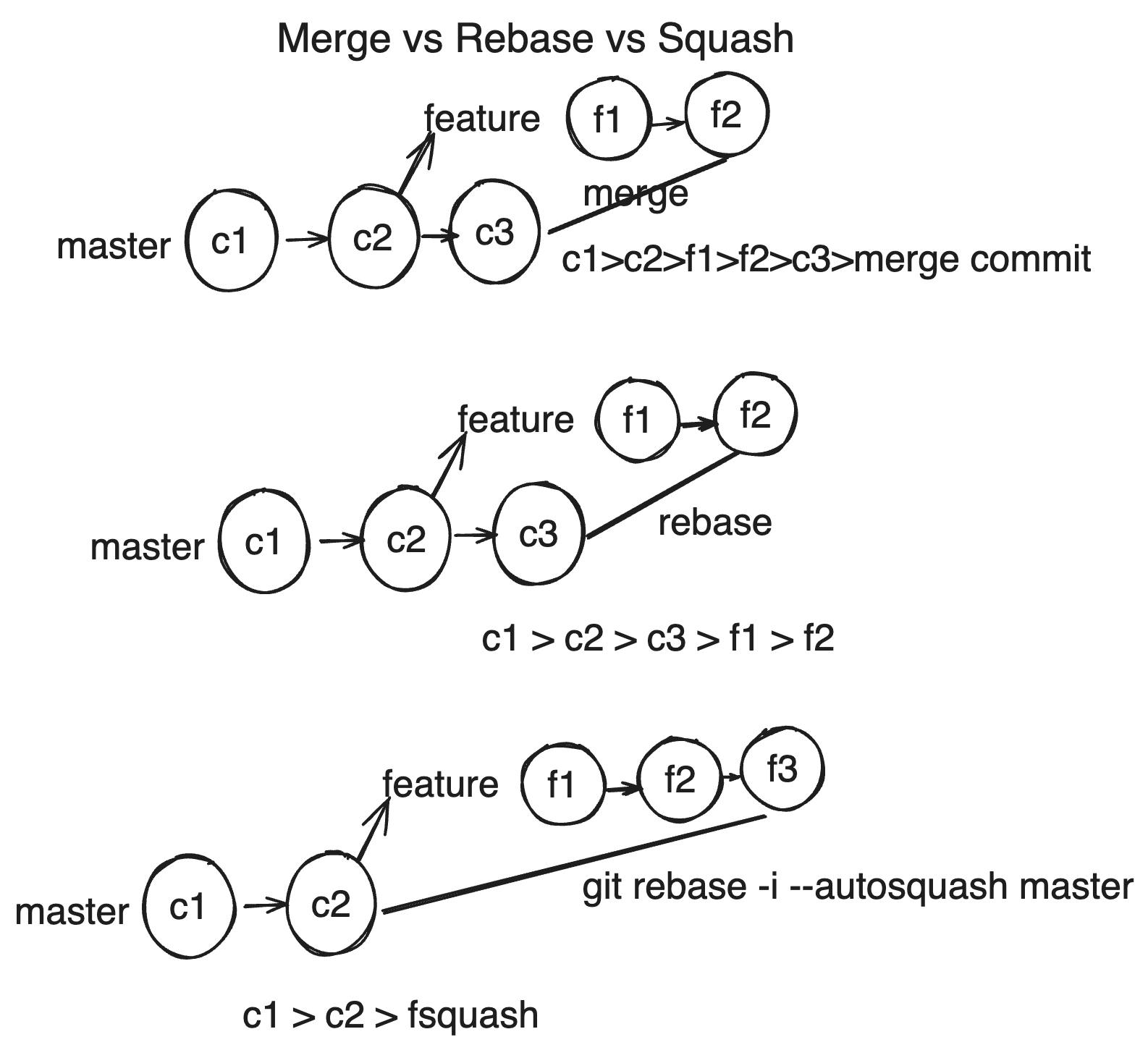

Both git merge and git rebase are used to integrate changes from one branch into another, but they do so in different ways. Understanding the difference between these two commands is crucial for managing your project's history effectively.

Git merge combines the contents of two branches, creating a new commit that represents the merge.

- How it works:

- When you merge one branch into another, Git creates a new "merge commit" that includes the histories of both branches.

- This preserves the history of the original branches, showing exactly when and where the branches diverged and were subsequently merged.

Example:

# Assuming you are on branch "feature" and want to merge "main" into it

git checkout feature

git merge mainAdvantages:

- Preserves History: Shows the full history of all branches, including where they diverged and merged.

- Clear Merge Points: Makes it easy to see when branches were merged.

Disadvantages:

- Messy History: The commit history can become cluttered with merge commits, especially in active projects with many branches.

- Conflicts: Conflicts may still arise and need to be resolved, just as with rebase.

Git rebase moves or "replays" commits from one branch onto another.

- How it works:

- Rebasing rewrites the commit history by creating new commits for each commit in the original branch, but based on the tip of the target branch.

- It effectively makes it look as if the commits in the original branch were created on top of the commits in the target branch.

Example:

# Assuming you are on branch "feature" and want to rebase onto "main"

git checkout feature

git rebase mainAdvantages:

- Cleaner History: The commit history is linear and easier to follow, with no merge commits cluttering the history.

- Bisecting: Easier to use

git bisectand other debugging tools because the history is simpler.

Disadvantages:

- Rewrites History: Rewriting history can be dangerous if not used carefully, especially if the branch has been shared with others.

- Complex Conflicts: Conflicts can still occur and may need to be resolved multiple times during the rebase process.

When to Use Merge:

- Preserve History: When you want to maintain a complete history of branch merges.

- Collaborative Workflows: When working with multiple collaborators, as it’s safer to merge branches that others may be working on.

When to Use Rebase:

- Clean History: When you want a cleaner, linear commit history.

- Local Changes: When you are working on local changes that haven’t been pushed to a shared repository yet.

Using Merge:

-

Create Feature Branch:

git checkout -b feature

-

Work on Feature:

git add . git commit -m "Work on feature"

-

Merge Main into Feature:

git checkout main git pull git checkout feature git merge main

Using Rebase:

-

Create Feature Branch:

git checkout -b feature

-

Work on Feature:

git add . git commit -m "Work on feature"

-

**Rebase Feature onto Main Using Rebase (continued):

-

Rebase Feature onto Main:

git checkout main git pull git checkout feature git rebase main

During the rebase process, if there are conflicts, Git will pause and allow you to resolve them. After resolving the conflicts, you would continue the rebase:

git add <resolved_files> git rebase --continue

-

Complete Rebase and Push Changes: Once the rebase is complete and all conflicts are resolved, you can push your rebased feature branch:

git push -f origin feature

Note: The

-f(force) option is required because rebase rewrites commit history, and Git will reject the push to prevent potential overwrites unless you force it.

Consider the following scenario where main has a linear commit history, and feature has diverged with additional commits.

-

Start with two branches:

git checkout -b main # Make some commits on main git checkout -b feature # Make some commits on feature

-

Merge

mainintofeature:git checkout main git pull git checkout feature git merge main

Resulting history:

* Merge branch 'main' into feature |\ | * Commit on main | * Another commit on main * | Commit on feature * | Another commit on feature |/ * Initial commit

-

Start with the same two branches:

git checkout -b main # Make some commits on main git checkout -b feature # Make some commits on feature

-

Rebase

featureontomain:git checkout main git pull git checkout feature git rebase main

Resulting history:

* Commit on feature * Another commit on feature * Commit on main * Another commit on main * Initial commit

- Git Merge: Combines branches by creating a merge commit, preserving the history of all commits and branches.

- Git Rebase: Moves the base of a branch to a new starting point, creating a linear history but rewriting commit history.

Both commands are powerful tools for managing branches and commits in Git. Choosing the right one depends on your project's workflow and how you prefer to manage your commit history. Merge is typically used for preserving a detailed history of branch merges, while rebase is used for creating a cleaner, linear history.

- git reset

- git revert

- git stash

- git tag

- git checkout

- git remote

- git stash is a powerful command that allows you to temporarily save changes in your working directory that you don't want to commit yet. This can be especially useful when you need to switch branches or pull in changes from a remote branch but your working directory isn't clean (i.e., it has modifications).

When you run git stash, Git takes your uncommitted changes (both staged and unstaged) and saves them on a stack of unfinished changes that you can reapply at any time.

-

Save Changes to Stash:

git stash

This command stashes both tracked (staged and unstaged) changes.

-

Apply Stashed Changes:

git stash apply

This command reapplies the most recently stashed changes but keeps them in the stash.

-

Apply and Remove Stashed Changes:

git stash pop

This command reapplies the most recently stashed changes and removes them from the stash.

-

List Stashed Changes:

git stash list

This command shows a list of all stashed changes.

-

Show Stashed Changes:

git stash show

This command shows a summary of changes in the most recent stash.

-

Show Detailed Stashed Changes:

git stash show -p

This command shows a detailed diff of changes in the most recent stash.

-

Stash Changes with a Message:

git stash save "message"This command allows you to stash changes with a custom message.

-

Apply a Specific Stash:

git stash apply stash@{2}This command applies the changes from a specific stash.

-

Drop a Specific Stash:

git stash drop stash@{2}This command deletes a specific stash.

-

Clear All Stashes:

git stash clear

This command deletes all stashes.

-

Make Changes in Your Working Directory:

echo "Some changes" >> file.txt git add file.txt

-

Stash the Changes:

git stash

Output:

Saved working directory and index state WIP on main: 1234567 Initial commit -

Verify the Stash:

git stash list

Output:

stash@{0}: WIP on main: 1234567 Initial commit -

Switch to Another Branch:

git checkout other-branch

-

Make Changes and Commit on the Other Branch:

echo "Work on other branch" >> other-file.txt git add other-file.txt git commit -m "Work on other branch"

-

Switch Back to the Original Branch:

git checkout main

-

Reapply Stashed Changes:

git stash pop

Output:

Auto-merging file.txt Dropped refs/stash@{

In GitHub, "tags" typically refer to Git tags. Git tags are a way to mark specific points in a Git repository's history as being important or significant. They are often used to label specific commits, such as releases or version numbers, to make it easier to reference those commits in the future.

Here's how Git tags work:

-

Creating a Tag: You can create a Git tag by running a command like

git tag <tag-name>, where<tag-name>is the name you want to give to the tag. For example, you might create a tag for a release like this:git tag v1.0.0. -

Tagging Commits: Tags are typically associated with specific commits. When you create a tag, it's linked to the current commit, but you can also specify a different commit if needed.

-

Listing Tags: You can list all the tags in a Git repository using the

git tagcommand. -

Annotated vs. Lightweight Tags: Git supports two types of tags: annotated and lightweight. Annotated tags are recommended for most use cases because they store extra metadata like the tagger's name, email, date, and a tagging message. Lightweight tags are just a name for a specific commit and don't include extra information.

-

Pushing Tags: By default, when you push changes to a remote Git repository, tags are not automatically pushed. You need to use

git push --tagsto push tags to a remote repository. This is important when you want to share tags, especially when creating releases on GitHub. -

Using Tags on GitHub: On GitHub, you'll often see tags associated with releases. When you create a release on GitHub, it typically creates a Git tag behind the scenes to mark the specific commit associated with that release. Users can then download or reference that release by its tag name.

GitHub also has its own concept of "releases" that are closely related to Git tags. A release on GitHub is a way to package and distribute software versions, and it often corresponds to a Git tag. When you create a GitHub release, you can upload release assets (e.g., binaries, documentation) and provide release notes.

In summary, GitHub tags are essentially Git tags, and they are used to mark important points in a repository's history, often associated with releases or significant commits. They help users easily reference and work with specific versions of a project.

To push your code to GitHub in a series of versions (v1, v2, v3, etc.) and track these versions, you can follow these steps. This involves creating tags or branches for each version, committing your changes, and pushing them to the remote repository on GitHub.

- Step 1: Initialize a Git Repository (If Not Done Already)

If you haven't initialized your project as a Git repository yet, do so:

git initThis will initialize a Git repository in your project folder.

- Step 2: Add and Commit Your Code for Version 1 (v1)

-

Add your code to the staging area:

git add . -

Commit the changes with a message indicating this is version 1:

git commit -m "Initial commit for version v1" -

Tag the commit as

v1:git tag v1

-

Push the code and the tag to GitHub:

git push origin main git push origin v1

- Step 3: Make Changes for Version 2 (v2)

-

Make changes to your code as needed for version 2.

-

Add and commit the changes:

git add . git commit -m "Changes for version v2"

-

Tag the commit as

v2:git tag v2

-

Push the code and the tag to GitHub:

git push origin main git push origin v2

- Step 4: Make Changes for Version 3 (v3)

-

Make changes to your code for version 3.

-

Add and commit the changes:

git add . git commit -m "Changes for version v3"

-

Tag the commit as

v3:git tag v3

-

Push the code and the tag to GitHub:

git push origin main git push origin v3

- Step 5: View the Versions on GitHub

- Go to your repository on GitHub.

- Click on the "Tags" section to view all the versions (

v1,v2,v3). - You will see the tags you pushed corresponding to the different versions of your code.

- Optional: Create Separate Branches for Each Version (Instead of Tags)

If you want to create branches for each version, follow these steps:

-

After committing your changes for each version, create a new branch for the version:

git checkout -b v1

-

Push the branch to GitHub:

git push origin v1

-

Repeat the process for

v2,v3, etc.git checkout -b v2 git push origin v2

- Tags are ideal for versioning releases (v1, v2, v3).

- Branches allow you to maintain separate development tracks for different versions if needed.

By following these steps, you can effectively track and view different versions of your code on GitHub.

Git squash is a process of combining multiple commits into a single commit. This is often done to clean up a commit history before merging into a main branch, making the commit history easier to understand and manage.

- Clean History: It helps to create a cleaner and more readable commit history.

- Logical Grouping: Combines related changes into a single commit, which can make it easier to understand the context of changes.

- Reduced Noise: Removes unnecessary commits, such as those with minor changes or fixes, that clutter the commit history.

You can squash commits using the interactive rebase feature in Git.

-

Start Interactive Rebase:

git rebase -i HEAD~3

This command will open an editor with a list of the last 3 commits.

-

Mark Commits to be Squashed:

-

In the editor, you'll see something like this:

pick abcdef1 Commit message 1 pick abcdef2 Commit message 2 pick abcdef3 Commit message 3 -

Change

picktosquash(ors) for the commits you want to squash:pick abcdef1 Commit message 1 squash abcdef2 Commit message 2 squash abcdef3 Commit message 3

-

-

Save and Exit the Editor:

- After marking the commits, save and close the editor. Git will then combine the commits.

-

Edit Commit Message:

- Another editor window will appear, allowing you to edit the commit message for the squashed commit. You can combine the commit messages or create a new one.

- Save and close the editor to complete the rebase.

Git squash is a powerful technique to streamline commit history, making it easier to review and understand. By using interactive rebase, you can squash multiple commits into one, ensuring your project history remains clean and meaningful.

- GitHub Pages

- GitHub Actions (CI/CD)

- Managing access permissions

- Using templates

- Webhooks

Git Flow GitHub Flow Trunk-Based Development Rewriting History

git cherry-pick git filter-branch git reflog Performance and Optimization

Partial clone Handling large repositories Git LFS (Large File Storage) Advanced GitHub Features

GitHub API Integrations with third-party tools Security best practices (code scanning, dependency checks) Collaboration and Workflow Automation

Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) with GitHub Actions Automating tasks with GitHub Apps and bots Git Internals

How Git stores objects and commits The Git object model Pack files and garbage collection