Define your system in Python using the elements and properties described in the pytm framework. Based on your definition, pytm can generate, a Data Flow Diagram (DFD), a Sequence Diagram and most important of all, threats to your system.

- Linux/MacOS

- Python 3.x

- Graphviz package

- Java (OpenJDK 10 or 11)

- plantuml.jar

tm.py [-h] [--debug] [--json] [--dfd] [--report REPORT] [--exclude EXCLUDE] [--seq] [--list] [--describe DESCRIBE] [--sqldump DBNAME]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--debug print debug messages

--dfd output DFD (default)

--report REPORT output report using the named template file (sample template file is under docs/template.md)

--exclude EXCLUDE specify threat IDs to be ignored

--seq output sequential diagram

--list list all available threats

--describe DESCRIBE describe the properties available for a given element

--sqldump DBNAME dumps all threat model elements and findings into the named sqlite file (erased if exists)

--json output a JSON file

Currently available elements are: TM, Element, Server, ExternalEntity, Datastore, Actor, Process, SetOfProcesses, Dataflow, Boundary and Lambda.

The available properties of an element can be listed by using --describe followed by the name of an element:

(pytm) ➜ pytm git:(master) ✗ ./tm.py --describe Element

Element class attributes:

OS

definesConnectionTimeout default: False

description

handlesResources default: False

implementsAuthenticationScheme default: False

implementsNonce default: False

inBoundary

inScope Is the element in scope of the threat model, default: True

isAdmin default: False

isHardened default: False

name required

onAWS default: False

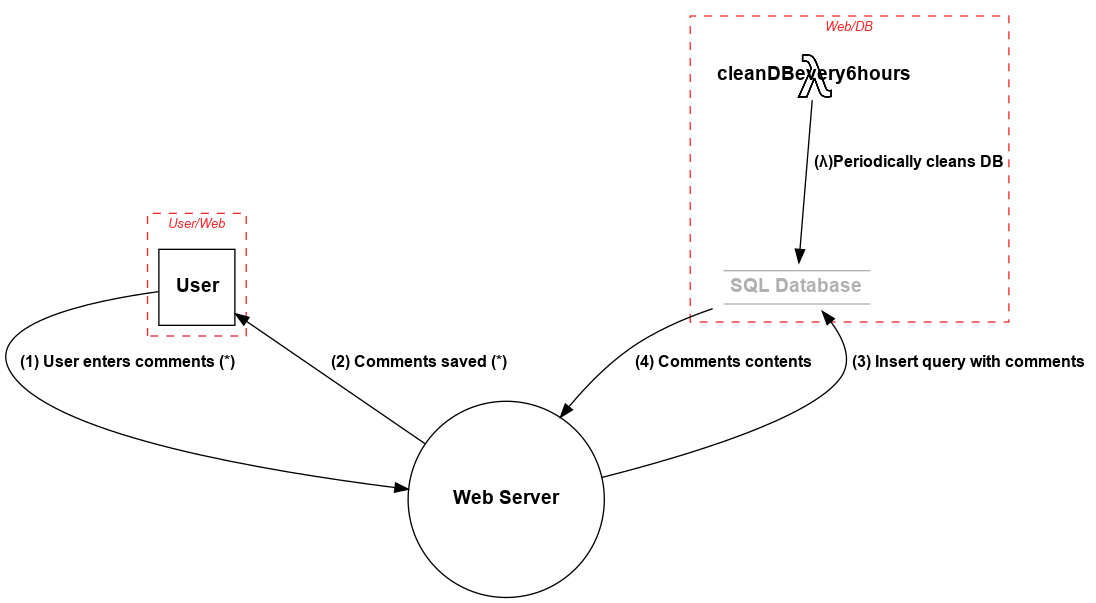

The following is a sample tm.py file that describes a simple application where a User logs into the application

and posts comments on the app. The app server stores those comments into the database. There is an AWS Lambda

that periodically cleans the Database.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pytm.pytm import TM, Server, Datastore, Dataflow, Boundary, Actor, Lambda

tm = TM("my test tm")

tm.description = "another test tm"

tm.isOrdered = True

User_Web = Boundary("User/Web")

Web_DB = Boundary("Web/DB")

user = Actor("User")

user.inBoundary = User_Web

web = Server("Web Server")

web.OS = "CloudOS"

web.isHardened = True

db = Datastore("SQL Database (*)")

db.OS = "CentOS"

db.isHardened = False

db.inBoundary = Web_DB

db.isSql = True

db.inScope = False

my_lambda = Lambda("cleanDBevery6hours")

my_lambda.hasAccessControl = True

my_lambda.inBoundary = Web_DB

my_lambda_to_db = Dataflow(my_lambda, db, "(λ)Periodically cleans DB")

my_lambda_to_db.protocol = "SQL"

my_lambda_to_db.dstPort = 3306

user_to_web = Dataflow(user, web, "User enters comments (*)")

user_to_web.protocol = "HTTP"

user_to_web.dstPort = 80

user_to_web.data = 'Comments in HTML or Markdown'

web_to_user = Dataflow(web, user, "Comments saved (*)")

web_to_user.protocol = "HTTP"

web_to_user.data = 'Ack of saving or error message, in JSON'

web_to_db = Dataflow(web, db, "Insert query with comments")

web_to_db.protocol = "MySQL"

web_to_db.dstPort = 3306

web_to_db.data = 'MySQL insert statement, all literals'

db_to_web = Dataflow(db, web, "Comments contents")

db_to_web.protocol = "MySQL"

db_to_web.data = 'Results of insert op'

tm.process()Diagrams are output as Dot and PlantUML.

When --dfd argument is passed to the above tm.py file it generates output to stdout, which is fed to Graphviz's dot to generate the Data Flow Diagram:

tm.py --dfd | dot -Tpng -o sample.png

Generates this diagram:

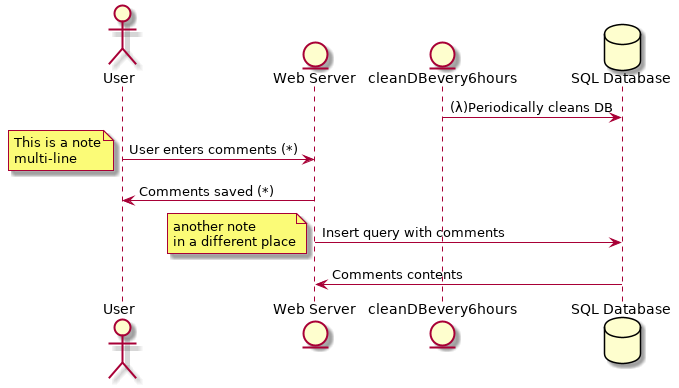

The following command generates a Sequence diagram.

tm.py --seq | java -Djava.awt.headless=true -jar plantuml.jar -tpng -pipe > seq.png

Generates this diagram:

The diagrams and findings can be included in the template to create a final report:

tm.py --report docs/template.md | pandoc -f markdown -t html > report.html

The templating format used in the report template is very simple:

# Threat Model Sample

***

## System Description

{tm.description}

## Dataflow Diagram

## Dataflows

Name|From|To |Data|Protocol|Port

----|----|---|----|--------|----

{dataflows:repeat:{{item.name}}|{{item.source.name}}|{{item.sink.name}}|{{item.data}}|{{item.protocol}}|{{item.dstPort}}

}

## Findings

{findings:repeat:* {{item.description}} on element "{{item.target}}"

}

To group findings by elements, use a more advanced, nested loop:

## Findings

{elements:repeat:{{item.findings:if:

### {{item.name}}

{{item.findings:repeat:

**Threat**: {{{{item.id}}}} - {{{{item.description}}}}

**Severity**: {{{{item.severity}}}}

**Mitigations**: {{{{item.mitigations}}}}

**References**: {{{{item.references}}}}

}}}}}

All items inside a loop must be escaped, doubling the braces, so {item.name} becomes {{item.name}}.

The example above uses two nested loops, so items in the inner loop must be escaped twice, that's why they're using four braces.

For the security practitioner, you may supply your own threats file by setting TM.threatsFile. It should contain entries like:

{

"SID":"INP01",

"target": ["Lambda","Process"],

"description": "Buffer Overflow via Environment Variables",

"details": "This attack pattern involves causing a buffer overflow through manipulation of environment variables. Once the attacker finds that they can modify an environment variable, they may try to overflow associated buffers. This attack leverages implicit trust often placed in environment variables.",

"Likelihood Of Attack": "High",

"severity": "High",

"condition": "target.usesEnvironmentVariables is True and target.sanitizesInput is False and target.checksInputBounds is False",

"prerequisites": "The application uses environment variables.An environment variable exposed to the user is vulnerable to a buffer overflow.The vulnerable environment variable uses untrusted data.Tainted data used in the environment variables is not properly validated. For instance boundary checking is not done before copying the input data to a buffer.",

"mitigations": "Do not expose environment variable to the user.Do not use untrusted data in your environment variables. Use a language or compiler that performs automatic bounds checking. There are tools such as Sharefuzz [R.10.3] which is an environment variable fuzzer for Unix that support loading a shared library. You can use Sharefuzz to determine if you are exposing an environment variable vulnerable to buffer overflow.",

"example": "Attack Example: Buffer Overflow in $HOME A buffer overflow in sccw allows local users to gain root access via the $HOME environmental variable. Attack Example: Buffer Overflow in TERM A buffer overflow in the rlogin program involves its consumption of the TERM environmental variable.",

"references": "https://capec.mitre.org/data/definitions/10.html, CVE-1999-0906, CVE-1999-0046, http://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/120.html, http://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/119.html, http://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/680.html"

}The target field lists classes of model elements to match this threat against.

Those can be assets, like: Actor, Datastore, Server, Process, SetOfProcesses, ExternalEntity,

Lambda or Element, which is the base class and matches any. It can also be a Dataflow that connects two assets.

All other fields (except condition) are available for display and can be used in the template

to list findings in the final report.

WARNING

The

threats.jsonfile contains strings that run througheval(). Make sure the file has correct permissions or risk having an attacker change the strings and cause you to run code on their behalf.

The logic lives in the condition, where members of target can be logically evaluated.

Returning a true means the rule generates a finding, otherwise, it is not a finding.

Condition may compare attributes of target and also call one of these methods:

target.oneOf(class, ...)whereclassis one or more: Actor, Datastore, Server, Process, SetOfProcesses, ExternalEntity, Lambda or Dataflow,target.crosses(Boundary),target.enters(Boundary),target.exits(Boundary),target.inside(Boundary).

If target is a Dataflow, remember you can access target.source and/or target.sink along with other attributes.

Conditions on assets can analyze all incoming and outgoing Dataflows by inspecting

the target.input and target.output attributes. For example, to match a threat only against

servers with incoming traffic, use any(target.inputs). A more advanced example,

matching elements connecting to SQL datastores, would be any(f.sink.oneOf(Datastore) and f.sink.isSQL for f in target.outputs).

INP01 - Buffer Overflow via Environment Variables

INP02 - Overflow Buffers

INP03 - Server Side Include (SSI) Injection

CR01 - Session Sidejacking

INP04 - HTTP Request Splitting

CR02 - Cross Site Tracing

INP05 - Command Line Execution through SQL Injection

INP06 - SQL Injection through SOAP Parameter Tampering

SC01 - JSON Hijacking (aka JavaScript Hijacking)

LB01 - API Manipulation

AA01 - Authentication Abuse/ByPass

DS01 - Excavation

DE01 - Interception

DE02 - Double Encoding

API01 - Exploit Test APIs

AC01 - Privilege Abuse

INP07 - Buffer Manipulation

AC02 - Shared Data Manipulation

DO01 - Flooding

HA01 - Path Traversal

AC03 - Subverting Environment Variable Values

DO02 - Excessive Allocation

DS02 - Try All Common Switches

INP08 - Format String Injection

INP09 - LDAP Injection

INP10 - Parameter Injection

INP11 - Relative Path Traversal

INP12 - Client-side Injection-induced Buffer Overflow

AC04 - XML Schema Poisoning

DO03 - XML Ping of the Death

AC05 - Content Spoofing

INP13 - Command Delimiters

INP14 - Input Data Manipulation

DE03 - Sniffing Attacks

CR03 - Dictionary-based Password Attack

API02 - Exploit Script-Based APIs

HA02 - White Box Reverse Engineering

DS03 - Footprinting

AC06 - Using Malicious Files

HA03 - Web Application Fingerprinting

SC02 - XSS Targeting Non-Script Elements

AC07 - Exploiting Incorrectly Configured Access Control Security Levels

INP15 - IMAP/SMTP Command Injection

HA04 - Reverse Engineering

SC03 - Embedding Scripts within Scripts

INP16 - PHP Remote File Inclusion

AA02 - Principal Spoof

CR04 - Session Credential Falsification through Forging

DO04 - XML Entity Expansion

DS04 - XSS Targeting Error Pages

SC04 - XSS Using Alternate Syntax

CR05 - Encryption Brute Forcing

AC08 - Manipulate Registry Information

DS05 - Lifting Sensitive Data Embedded in Cache

SC05 - Removing Important Client Functionality

INP17 - XSS Using MIME Type Mismatch

AA03 - Exploitation of Trusted Credentials

AC09 - Functionality Misuse

INP18 - Fuzzing and observing application log data/errors for application mapping

CR06 - Communication Channel Manipulation

AC10 - Exploiting Incorrectly Configured SSL

CR07 - XML Routing Detour Attacks

AA04 - Exploiting Trust in Client

CR08 - Client-Server Protocol Manipulation

INP19 - XML External Entities Blowup

INP20 - iFrame Overlay

AC11 - Session Credential Falsification through Manipulation

INP21 - DTD Injection

INP22 - XML Attribute Blowup

INP23 - File Content Injection

DO05 - XML Nested Payloads

AC12 - Privilege Escalation

AC13 - Hijacking a privileged process

AC14 - Catching exception throw/signal from privileged block

INP24 - Filter Failure through Buffer Overflow

INP25 - Resource Injection

INP26 - Code Injection

INP27 - XSS Targeting HTML Attributes

INP28 - XSS Targeting URI Placeholders

INP29 - XSS Using Doubled Characters

INP30 - XSS Using Invalid Characters

INP31 - Command Injection

INP32 - XML Injection

INP33 - Remote Code Inclusion

INP34 - SOAP Array Overflow

INP35 - Leverage Alternate Encoding

DE04 - Audit Log Manipulation

AC15 - Schema Poisoning

INP36 - HTTP Response Smuggling

INP37 - HTTP Request Smuggling

INP38 - DOM-Based XSS

AC16 - Session Credential Falsification through Prediction

INP39 - Reflected XSS

INP40 - Stored XSS

AC17 - Session Hijacking - ServerSide

AC18 - Session Hijacking - ClientSide

INP41 - Argument Injection

AC19 - Reusing Session IDs (aka Session Replay) - ServerSide

AC20 - Reusing Session IDs (aka Session Replay) - ClientSide

AC21 - Cross Site Request Forgery