| 📝 |

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px">

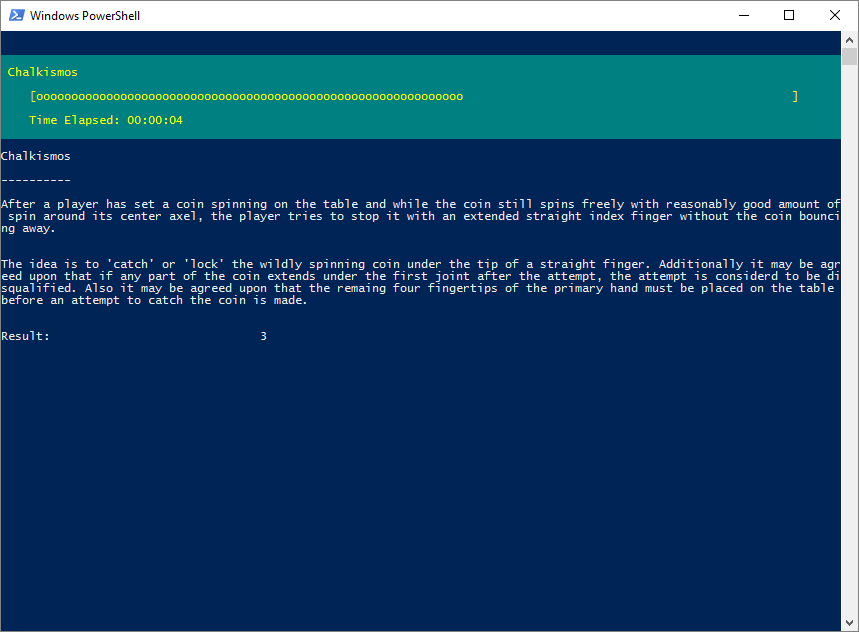

<p>In the game called χαλκισμός (chalkismos) the player had to spin a coin on the table and then stop it with an extended index finger without the coin falling over. The date of invention is not known but Ἰούλιος Πολυδεύκης Ναυκρατίτης (a.k.a. Julius Pollux) reports that the greatest master of the game was Φρύνη (a.k.a. Μνησαρέτη a.k.a. Phryne, born c. 371 BC), the famous courtesan (ἑταίρα) in the second half of 4th c. BC. [1]</p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p>"Καὶ μὴν καὶ ἄλλαι παιδιαὶ αἵδε πaρεoικυῖαι τῷ σχήματι τῆς λέξεως, χαλκισμὸς, ἱμαντελιγμὸς, ἐφεδρισμὸς, ἐποστρακισμὸς, ἀσκωλιασμός. Ό μὲν χαλκισμὸς, ὀρθὸν νόμισμα ἔδει συντόνως περιστρέψαντας ἐπιστρεφόμενον ἐπιστῆσαι τῷ δακτύλω. ᾧ τρόπῳ μάλιστα τῆς παιδιᾶς ὑπερήδεσθαί φασι Φρύνην τἠν ἑταίραν."</p>

<p><b> Ἰούλιος Πολυδεύκης Ναυκρατίτης </b>(2nd century AD) a.k.a. Julius Pollux: 'Ὀνομαστικόν' (Onomasticon): Vol. IX, 118. [2]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px"><h3>Capita aut navia?</h3>

<!--

/ | () | | | () |

| | __ _ _ __ | | __ _ __ _ _ | | _ __ __ ___ ___ __ _ ) |

| | / | '_ \| | __/ _ | / | | | | __| | '_ \ / _ \ \ / / |/ ` |/ /

| || (| | |) | | || (| | | (| | || | | | | | | (| |\ V /| | (| ||

__,| .__/||__,| _,|_,|_| || ||_,| _/ ||_,()

| |

|_| -->

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px">

<p>In antiquity within the Roman cultural sphere, the commonly used name for the game of 'heads or tails' was 'capita aut navia' (heads or a ship), which, perhaps, could also be considered as the original ancestral name of the game of 'heads or tails'. The name might have derived from the early Roman Republic coinage that had the double-faced head of Ianus a.k.a. Janus on the obverse and the prow of a ship on the reverse. Ianus was a deity considered by Romans to be the first king of Latium on the site of the city before its foundation and was believed to have two faces: to see what was going on in front and behind him; who knew the past and foresaw the future. The prow of a ship or a full ship would resemble the ship on which Saturnus a.k.a. Saturn arrived to Ianiculum a.k.a. Janiculum after been expelled from the heavens by Iuppiter a.k.a. Jupiter a.k.a. Jove. The existence of such coins and the aforementioned backstory is hinted by an anonomous author in a short work called '<i>Origo Gentis Romanae</i>' ("The Origins of the Roman People"), which was composed perhaps sometime in the fourth century AD, which used to be credited to the Roman historian Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), but currently is not assigned to any particular author, where Ianus is said to be the one that directly taught the ancient Romans how to work with bronze and how to put the money in a form of a coin. Furhermore it seems to be indicated that on those coins on one side would be the head of Ianus, the mentor himself, and on the other side the ship that had brought Saturnus a.k.a. Saturn to Latium: [3] </p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p>"Igitur Iano regnante apud indigenas rudes incultosque Saturnus regno profugus, cum in Italiam devenisset, benigne exceptus hospitio est ibique haud procul a Ianiculo arcem suo nomine Saturniam constituit. Isque primus agriculturam edocuit ferosque homines et rapto vivere assuetos ad compositam vitam eduxit, secundum quod <b>Vergilius</b> in octavo sic ait:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>Haec loca indigenae Fauni Nymphaeque tenebant,

<br />Gensque virum truncis et duro robore nata,

<br />Quis neque mos neque cultus erat nec iungere tauros

<br />Aut componere opes norant aut parcere parto,

<br />Sed rami atque asper victu venatus alebat.</i> [Aen. VIII.314-318]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />Omissoque Iano, qui nihil aliud quam ritum colendorum deorum religionesque intulerat, se Saturno maluit annectere, qui vitam moresque feris etiam tum mentibus insinuans ad communem utilitatem, ut supra diximus, disciplinam colendi ruris edocuit, ut quidem indicant illi versus:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>Is genus indocile ac dispersum montibus altis

<br />Composuit legesque dedit Latiumque vocari

<br />Maluit.</i> [Aen. VIII.321-323]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />Is tum etiam usum signandi aeris ac monetae in formam incutiendae ostendisse traditur, in quam ab una parte caput eius imprimeretur, altera navis, qua vectus illo erat. Unde hodieque aleatores posito nummo opertoque optionem collusoribus ponunt enuntiandi, quid putent subesse, caput, aut navem: quod nunc vulgo corrumpentes naviam dicunt. Aedes quoque sub clivo Capitolino, in qua pecuniam conditam habebat, aerarium Saturni hodieque dicitur. Verum quia, ut supra diximus, prior illuc Ianus advenerat, cum eos post obitum divinis honoribus cumulandos censuissent, in sacris omnibus primum locum Iano detuleruat, usque eo, ut etiam, cum aliis diis sacrificium fit, dato ture in altaria, Ianus prior nominetur, cognomento quoque addito Pater, secundum quod noster sic intulit:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>Hanc Ianus Pater, hanc Saturnus condidit arcem.</i> [Aen. VIII.357]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />Ac subinde: <i>Ianiculum huic, illi fuerat Saturnia nomen.</i> [Aen. VIII.358]

<br />

<br />Eique, eo quod mire praeteritorum memor, tum etiani futuri..."</p>

<p>Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – <b>Sextus Aurelius Victor</b> (c. AD 320–390): 'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:1-7. [4]</p>

</blockquote>

<h4>Translation</h4>

<p>Translated by: Kyle Haniszewski, Lindsay Karas, Kevin Koch, Emily Parobek, Colin Pratt, and Brian Serwicki; Thomas M. Banchich, Supervisor</p>

<blockquote>

<p>"Therefore, while Janus was reigning among unrefined and unpolished natives, Saturnus, having fled his realm, was warmly received with hospitality when he had arrived in Italy and there, not far from the Janiculum, founded a stronghold with his own name, Saturnia. And he first taught agriculture and introduced to a settled life men savage and accustomed to live by plunder, in accordance with which <b>Virgil</b> in Book VIII speaks thus:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>These spots native Fauns and Nymphs used to hold,

<br />And a race of men from trunks and rough wood born,

<br />Who knew neither tradition nor reverence nor how to yoke bulls

<br />Nor to lay away resources or to preserve a part of what had been obtained,

<br />But fed from the bough and fierce victim of the hunt.</i> [Aen. VIII.314-318]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />And with Janus, who had introduced nothing other than the practice of reverence of the gods and religious ceremonies, omitted, he preferred to turn his attention to Saturnus, who, as we said above, introducing to minds even then savage a way of life and habits conducive to the common good, taught the art of tending the field, as, indeed, these verses demonstrate:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>He this race, restless and scattered in lofty mountains,

<br />Did unify and gave them laws and preferred it to be called

<br />Latium.</i> [Aen. VIII.321-323]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />Then, too, he is said to have introduced the practice of marking bronze and of striking coinage in a die in which from one his head was imprinted, from the other the ship by which he had been borne there. Whence even to this day gamblers, when a coin has been set down and covered, lay as a wager to players the option of declaring what they think is underneath, a head or a ship [navis], which now, commonly adulterating, they pronounce *shrudder* [navia]. Also, the building beneath the Capitoline slope in which he used to keep the coinage which had been produced is to this day called Saturnus' Treasury. In fact, because, as we said above, Janus had arrived before him, when, after their deaths, they reckoned that these men must be loaded with divine honors, in all religious ceremonies they assigned first place to Janus, with the result that, even when a sacrifice is made to other gods, when incense has been offered at the altars, Janus is named first, with the cognomen "Father" also added, in accordance with which our man did thus produce:

<br />

<br /><ol><ol><ol><i>This base did Father Janus, this did Saturnus found.</i> [Aen. VIII.357]</ol></ol></ol>

<br />

<br />And immediately thereafter: <i>Janiculum was the name for the one, Saturnia for the other.</i> [Aen. VIII.358]

<br />

<br />And to him, because of a wondrous memory of things past as well as of the future..."</p>

<p>Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – <b>Sextus Aurelius Victor</b> (c. AD 320–390): 'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:1-7. [5]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>In the first book of '<i>Fasti</i>' (The Festivals), which was dedicated to Germanicus (15 BC – AD 19, a.k.a. Germanicus Julius Caesar a.k.a. Nero Claudius Drusus or Tiberius Claudius Nero), the author, P. Ovidius Naso (43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid) tells that while he had an encounter with Ianus, which was not just a simple real-life revelation of a god, but also a dialogue, too, with a god, Ianus enlightened the author on varying subjects, such as why and how did he have such distinctively shaped head with two faces, and then promptly proceeded to answear all the questions that Ovidius was eager to ask. The following is an exerpt of the dialogue between Ovidius and Ianus as per recorded by Ovidius, in which, for example, the expulsion of Saturnus from the celestial realms is reflected, and a godly answear to the question "Why is the figure of a ship stamped on one side of the copper coin, and a two-headed figure on the other?" is revealed:</p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<strong>Ovidius: </strong>"Quid volt palma sibi rugosaque carica," dixi, "et data sub niveo candida mella cado?"

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"Omen," ait, "causa est, ut res sapor ille sequatur et peragat coeptum dulcis ut annus iter."

<br />

<br /><strong>Ovidius: </strong>"Dulcia cur dentur, video, stipis adice causam, pars mihi de festo ne labet ulla tuo."

<br />

<br />Risit et

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"O quam te fallunt tua saecula," dixit, "qui stipe mel sumpta dulcius esse putes [putas]! vix ego Saturno quemquam regnante videbam, cuius non animo dulcia lucra forent. Tempore crevit amor, qui nunc est summus, habendi vix ultra, quo iam progrediatur, habet. Pluris opes nunc sunt, quam prisci temporis annis, dum populus pauper, dum nova Roma fuit, dum casa Martigenam capiebat parva Quirinum, et dabat exiguum fluminis ulva torum. Iuppiter angusta vix totus stabat in aede, inque Iovis dextra fictile fulmen erat. Frondibus ornabant quae nunc Capitolia gemmis, pascebatque suas ipse senator oves; nec pudor in stipula placidam cepisse quietera [quietem] et faenum capiti supposuisse [subposuisse] fuit. Iura dabat populis posito modo praetor aratro, et levis argenti lammina crimen erat. At postquam fortuna loci caput extulit huius, et tetigit summos [summo] vertice Roma deos, creverunt et opes et opum furiosa cupido, et, cum possideant plurima, plura petunt. Quaerere, ut absumant, absumpta requirere certant, atque ipsae vitiis sunt alimenta vices. Sic quibus intumuit suffusa venter ab unda, quo plus sunt potae, plus sitiuntur aquae. In pretio pretium nunc est: dat census honores, census amicitias: pauper ubique iacet.

<br />

<br />Tu tamen auspicium si sit stipis utile, quaeris, curque iuvent vestras aera vetusta manus? Aera dabant olim, melius nunc omen in auro est, victaque concessit prisca moneta novae, nos quoque templa iuvant, quamvis antiqua probemus, aurea: maiestas convenit ista [ipsa] deo. Laudamus veteres, sed nostris utimur annis: mos tamen est aeque dignus uterque coli."

<br />

<br />Finierat monitus. placidis ita rursus, ut ante, clavigerum verbis adloquor ipse deum:

<br />

<br /><strong>Ovidius: </strong>"Multa quidem didici: sed cur navalis in aere altera signata est, altera forma biceps?"

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"Noscere me duplici posses sub imagine," dixit, "ni vetus ipsa dies extenuasset opus, causa ratis superest: Tuscum rate venit in [ad] amnem ante pererrato falcifer orbe deus. hac ego Saturnum memini tellure receptum caelitibus regnis a Iove pulsus erat. Inde diu genti mansit Saturnia nomen; dicta quoque est Latium terra, latente deo. At bona posteritas puppem formavit in aere, hospitis adventum testificata dei. Ipse solum colui, cuius placidissima laevum radit harenosi Thybridis unda latus. Hic, ubi nunc Roma est, incaedua silva virebat, tantaque res paucis pascua bubus erat. Arx mea collis erat, quem volgus [volgo] nomine nostro nuncupat, haec aetas Ianiculumque vocat. Tunc ego regnabam, patiens cum terra deorum esset, et humanis numina mixta locis. Nondum Iustitiam facinus mortale fugarat (ultima de superis illa reliquit humum), proque metu populum sine vi pudor ipse regebat; nullus erat iustis reddere iura labor, nil mihi cum bello: pacem postesque tuebar et" clavem ostendens "haec," ait, "arma gero."

<br />

<br />Presserat ora deus.

<p>(Ov. Fast. 1, 185—255):<b> P. Ovidius Naso </b>(43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid): 'Fasti' (The Festivals) 1:235—255 [6]</p>

</blockquote>

<h4>Translation</h4>

<blockquote>

<strong>Ovidius: </strong>"What mean the gifts of dates and wrinkled figs," I said, "and honey glistering in snow-white jar?"

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"It is for the sake of the omen," said he, "that the event may answer to the flavour, and that the whole course of the year may be sweet, like its beginning."

<br />

<br /><strong>Ovidius: </strong>"I see," said I, "why sweets are given. But tell me, too, the reason for the gift of cash, that I may be sure of every point in thy festival."

<br />

<br />The god laughed, and

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"Oh," quoth he, "how little you know about the age you have in if you fancy that honey is sweeter than cash in hand! Why, even in Saturn's reign I hardly saw a soul who did not in his heart find lucre sweet. As time went on the love of pelf grew, till now it is at its height and scarcely can go farther. Wealth is more valued now than in the years of old, when the people were poor, when Rome was new, when a small hut sufficed to lodge Quirinus, son of Mars, and the river sedge supplied a scanty bedding. Jupiter had hardly room to stand upright in his cramped shrine, and in his right hand was a thunderbolt of clay. They decked with leaves the Capitol, which now they deck with gems, and the senator himself fed his own sheep. It was no shame to take one's peaceful rest on straw and to pillow the head on hay. The praetor put aside the plough to judge the people, and to own a light piece of silver plate was a crime. But ever since the Fortune of this place has raised her head on high, and Rome with her crest has touched the topmost gods, riches have grown and with them the frantic lust of wealth, and they who have the most possessions still crave for more. They strive to gain that they may waste, and then to repair their wasted fortunes, and thus they feed their vices by ringing the changes on them. So he whose belly swells with dropsy, the more he drinks, the thirstier he grows. Nowadays nothing but money counts: fortune brings honours, friendships; the poor man everywhere lies low.

<br />

<br />And still you ask me. What's the use of omens drawn from cash, and why do ancient coppers tickle your palms! In the olden time the gifts were coppers, but now gold gives a better omen, and the old-fashioned coin has been vanquished and made way for the new. We, too, are tickled by golden temples, though we approve of the ancient ones: such majesty befits a god. We praise the past, but use the present years; yet are both customs worthy to be kept."

<br />

<br />He closed his admonitions but again in calm speech, as before, I addressed the god who bears the key:

<br />

<br /><strong>Ovidius: </strong>"I have learned much indeed; but why is the figure of a ship stamped on one side of the copper coin, and a two-headed figure on the other?"

<br />

<br /><strong>Ianus: </strong>"Under the double image," said he, "you might have recognized myself, if the long lapse of time had not worn the type away. Now for the reason of the ship. In a ship the sickle-bearing god came to the Tuscan river after wandering over the world. I remember how Saturn was received in this land: he had been driven by Jupiter from the celestial realms. From that time the folk long retained the name of Saturnian, and the country, too, was called Latium from the hiding (latente) of the god. But a pious posterity inscribed a ship on the copper money to commemorate the coming of the stranger god. Myself inhabited the ground whose left side (is lapped by) sandy Tiber's glassy wave. Here, where now is Rome, green forest stood unfelled, and all this mighty region was but a pasture for a few kine. My castle was the hill which common folk call by my name, and which this present age doth dub Janiculum. I reigned in days when earth could bear with gods, and divinities moved freely in the abodes of men. The sin of mortals had not yet put Justice to flight (she was the last of the celestials to forsake the earth): honour's self, not fear, ruled the people without appeal to force: toil there was none to expound the right to righteous men. I had naught to do with war: guardian was I of peace and doorways, and these," quoth he, showing the key, "these be the arms I bear."

<br />

<br />The god now closed his lips.

<p>(Ov. Fast. 1, 185—255):<b> P. Ovidius Naso </b>(43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid): 'Fasti' (The Festivals) 1:235—255 [6]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>It cannot get more authorative than that, you heard the answear to the question "Why is the figure of a ship stamped on one side of the copper coin, and a two-headed figure on the other?" straight from Ianus himself, as narrated by Ovidius. Apparently a fourth–fifth century Christian (Roman) writer and churchman Pontius Paulinus Nolanus (c. AD 353—431, a.k.a. Pontius Meropius Anicius Paulinus a.k.a. Paulinus of Nola (who, about after AD 409, was chosen to be the Bishop of Nola)) had heard of this story as well, since he does describe matters in a similar way, when he discusses briefly why some things are called as they are called and with a striking similarity with Ovidius' view desciribes how the '<i>capita</i>' became to signify one side of a coin and '<i>navia</i>' the other side of the coin in this brief excerpt from one of his poems, which were mostly written in Nola, Campania, where each year after AD 395 he would write a poem in honor of the saint (St.) Felix, to whom he credited his conversion to and who actually was also buried in Nola: [7] </p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p>"Nomen habet certe quod nec ratione probetur. Sacra Ioui faciunt et 'Iuppiter Optime' dicunt huncque rogant, et 'Iane Pater' primo ordine ponunt. Rex fuit hic Ianus proprio qui nomine fecit Ianiculum, prudens homo, qui cum multa futura posset respicere, (et) duplici hunc pinxere figura et Ianum geminum veteres dixere Latini. Hic quia navigio Ausonias aduenit ad oras, nummus huic primum tali est excussus honore, ut pars una caput, pars sculperet altera navem; cuius nunc memores quaecumque nomismata signant, ex veteri facto 'capita' haec 'et navia' dicunt."</p>

<p><b>Pontius Paulinus Nolanus</b> (c. AD 353–431) a.k.a. Pontius Meropius Anicius Paulinus a.k.a. Paulinus of Nola: 'Carmina' (Carmen, Poëm, Poem) 32:65—77. [8]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>In the game of '<i>capita aut navia</i>' itself, a play of the Roman youth or the "gamblers" <i>aleatores</i> mentioned above, a piece of money was thrown up to see whether the figure-side a.k.a. obverse (the double-faced head of Ianus) or the reverse-side (a ship) will fall uppermost. The heads of Ianus and the prora were first used in the Roman coinage around 225 BC, which might designate the earliest date for the invention of the game in its current form, though without any doubt children have been flinging coins before that with varying game-play modes. Children may, indeed, have something to do with the very name of the game itself, too, since the word '<i>navia</i>' actually doesn't seem to be a proper Latin word at all: [9]</p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<p><i>caput, capitis</i> = 'a head'</p>

<p><i>navis, navis</i> = 'a ship'</p>

<p><i>navia, naviae</i> = 'a ship' — A corruption of <i>navis</i>, 'a ship'; used for instance in the proverb

<br />'<i>aut caputa aut naviam</i>' [sic] instead of the more linguistically correct forms of

<br /> '<i>aut caput aut navem</i>' (singular acc) or '<i>aut capita aut naves</i>' (plural acc) [10]</p>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>One of the earliest times that this linguistical atrocity rotting the very essence, how and in which way things are named, was in the fourth century in the third chapter of '<i>Origo Gentis Romanae</i>' ("The Origins of the Roman People"), which used to be credited to the Roman historian Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), but currently is not assigned to any particular author, where this unknown author pointed out, that it would be better to use '<i>navem</i>' instead of the "vulgar" or "corrupted" word of '<i>navia</i>'... </p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p><i>"Unde hodieque aleatores posito nummo opertoque optionem collusoribus ponunt enuntiandi, quid putent subesse: caput, aut navem; quod nunc vulgo corrumpentes naviam dicunt."</i></p>

<p>Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – <b>Sextus Aurelius Victor</b> (c. AD 320–390): 'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:5. [11]</p>

</blockquote>

<h4>Translation</h4>

<blockquote>

<p>"That is why even today gamblers, after a coin has been put down and hidden, announce to their fellow gambler the choice, which one could be underneath: head or ship; which now the common people say corruptly 'navia'."</p>

<p>Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – <b>Sextus Aurelius Victor</b> (c. AD 320–390): 'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:5. [11]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>It must be noted, though, that since the fourth century the vulgarity of the '<i>navia</i>' term has faded gradually, and its usage has became more widely accepted (O tempore, o mores...), but still, one can only wonder, how this anomality came into being and furhermore, how it even surpassed the 'linguistically correct' version and flourished throughout the centuries despite what was being depicted on the coins.</p>

<p>'<i>Navia</i>', however, did become so enrooted in the cultural landscape of Rome, that even the early Church Fathers used it occasionally without a blink of an eye instead of the more correct word forms, as demonstrated above by the Bishop of Nola. The word '<i>navia</i>' is used in a more condemning manner by Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis a.k.a. Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430) in '<i>De Anima et Eius Origine, Liber IV</i>' (A Treatise on the Soul and Its Origin, Book IV) Chapter 20 [XIV] called 'Quisnam sit interior videamus: utrum anima, an spiritus, an utrumque' (What kind of an inner man do we see: the soul, the spirit or both) where, while trying to refute a worldview, in which a man consists of three parts (the outer, the inner and the inmost), Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis uses '<i>caput et navia</i>' as a direct reference point (

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<p><i>"sicut in nummo dicitur 'caput et navia'"</i></p>

<p><b>Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis</b> (AD 354–430, a.k.a. Augustine of Hippo ): 'De Anima et Eius Origine, Liber IV' (A Treatise on the Soul and Its Origin, Book IV) Chapter 20 [XIV] [12]</p>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

) in an hypothetical example of how the three-part-man could be "refashioned after the image of god" by "receiveing god's image" or by "being renewed in the knowledge of god". Though Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis had adhered to Manichaeism and also for some time had favoured the scepticism of the New Academy and had converted to Catholicism in AD 387 and had became the Bishop of Hippo in AD 395 and had held the position for about 23 years at the time of the publication of the '<i>navia</i>'-text, which was written towards the end of AD 419, he was not, by any means, an uneducated person, but still he used the same 'incorrect' word as the "gamblers" <i>aleatores</i> on the street, when addressing to the sides of a coin, which, by judging only by the choise of words, according to Cicero, would place him in the same category as the adulterers and all the other unclean and shameless citizens. [13]

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p><i>"(Postremum autem genus...) In his gregibus omnes aleatores, omnes adulteri, omnes impuri impudicique versantur."</i></p>

<p>(Cic. Catil. 2.10.22–23) <b>Marcus Tullius Cicero</b> a.k.a. Κικέρων, (106–43 BC): 'M. Tulli Ciceronis in L. Catilinam orationes quattuor': In L. Catilinam Oratio Secunda Habita Ad Populum 10.22–23 (The Second oration of Marcus Tullius Cicero against Lucius Catilina, Addressed to the People. 10.22–23) [14]</p>

</blockquote>

<h4>Translation</h4>

<blockquote>

<p>"(The last class...) In these crowds are all the gamblers, all the adulterers, all the unclean and shameless citizens."</p>

<p>(Cic. Catil. 2.10.22–23) <b>Marcus Tullius Cicero</b> a.k.a. Κικέρων, (106–43 BC): 'M. Tulli Ciceronis in L. Catilinam orationes quattuor': In L. Catilinam Oratio Secunda Habita Ad Populum 10.22–23 (The Second oration of Marcus Tullius Cicero against Lucius Catilina, Addressed to the People. 10.22–23) [14]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>A fifth century Roman author Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius records perhaps the clearest example of this ancient version of the 'heads' or 'tails' game in the the seventh chapter of the first book in the seven book Saturnalia series. It truly is striking, how the name of the game had persisted throughout the centuries in spite of the fact that the design of the Roman coinage had changed radically by Macrobius' period. [15]</p>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<ol>

<blockquote>

<p>"Regionem istam, quae nunc vocatur Italia, regno Ianus optinuit, qui, ut Hyginus Protarchum Trallianum secutus tradit, cum Camese aeque indigena terram hanc ita participata potentia possidebant, ut regio Camesene, oppidum Ianiculum vocitaretur. Post ad Ianum solum regnum redactum est, qui creditur geminam faciem praetulisse, ut quae ante quaeque post tergum essent intueretur: quod procul dubio ad prudentiam regis sollertiamque referendum est, qui et praeterita nosset et futura prospiceret, sicut Antevorta et Postvorta, divinitatis scilicet aptissimae comites, apud Romanos coluntur. Hic igitur Ianus, cum Saturnum classe pervectum excepisset hospitio et ab eo edoctus peritiam ruris ferum illum et rudem ante fruges cognitas victum in melius redegisset, regni eum societate muneravit. Cum primus quoque aera signaret, servavit et in hoc Saturni reverentiam, ut, quoniam ille navi fuerat advectus, ex una quidem parte sui capitis effigies, ex altera vero navis exprimeretur, quo Saturni memoriam in posteros propagaret. Aes ita fuisse signatum hodieque intellegitur in aleae lusum, cum pueri denarios in sublime iactantes capita aut navia lusu teste vetustatis exclamant."</p>

<p><b>Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius</b> (ca. AD 385/390—430) a.k.a. Macrobius: Macrobii Theodosii (viri) Illustrissimi Saturnaliorum Libri I 7:19—22 (The Saturnalia, Book 1: 7:19—22). [16]</p>

</blockquote>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

</ol>

<p>Despite Macrobius, too, says that Ianus was the first who impressed upon copper coins anything, the first figures may actually have been that of sheep and oxen by the legendary sixth king of Rome, Servius Tullius (578—535 BC) who in reality might also have been the first to have an impress made upon copper coins.[17]</p>

<p>Before Servius Tullius' time, according Τιμαῖος (c. 350–260 BC, a.k.a. Timaios a.k.a. Timaeus of Taormina a.k.a. Tauromenium a.k.a. Ταυρομένιον, who wrote '<i>The Histories</i>' containing the history of Greece from its earliest days untill the first Punic war and was according to Πολύβιος (c. 200–118 BC, a.k.a. Polybius) popularly regarded as 'the first historian of Rome'), at Rome the raw metal only was used. [18] The form of a sheep was widely believed to be the first figure impressed upon money, and to this fact it was said it owes its name, '<i>pecunia</i>.'[19]</p>

<p>Silver was not impressed with a mark until the year of the City 485 (269 BC), the year of the consulship of Q. Ogulnius Gallus and C. Fabius Pictor and five years before the First Punic War (264—241 BC), at which time it was ordained that the value of the currency should follow along similar lines to what is being depicted below: [20]</p>

<ol>

<h4>Values in 269 BC:</h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Value</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Metric</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>British derived customary systems</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>denarius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">ten librae of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">3274.5 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">115.5046 oz</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>quinarius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">five librae of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">1637.25 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">57.75229 oz</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>sestertius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">two librae and a half of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">818.625 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">28.87615 oz [20]</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

<p>The weight, however, of the <i>libra</i> of copper was diminished during the First Punic War, as the republic was not having the means to meet its expenditure — in consequence of which, an ordinance was made that the '<i>as</i>' [21] should in future be struck of two ounces weight. By this contrivance a saving of nearly five-sixths (82,7 %) was gained, and the public debt was liquidated. The impression upon these new "reduced" copper coins was a two-faced Ianus on one side, and the beak of a ship of war on the other: the <i>triens</i> (one third of an '<i>as</i>') however, and the <i>quadrans</i> (one fourth of an '<i>as</i>') bore the impression of a ship. The <i>quadrans</i>, too, had, previously to this, been called '<i>teruncius</i>', as being three <i>unciae</i> (one twelveth of an '<i>as</i>') in weight. [22]</p>

<p>At a later period again, when Hannibal was pressing hard upon Rome, during the ************ of Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus Cunctator (c. 280—203 BC), '<i>asses</i>' of one ounce weight were struck, and it was ordained that the value of the currency should follow similar guidelines to which are depicted below:... [23]</p>

<ol>

<h4>Values in 218–204 BC:</h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Value</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Metric</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>British derived customary systems</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>denarius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">sixteen asses of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">453.5924 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">16 oz</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>quinarius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">eight asses of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">226.7962 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">8 oz</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>sestertius</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">four asses of copper</td>

<td style="padding:6px">113.3981 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">4 oz [23]</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

<p>by which last reduction of the weight of the '<i>as</i>' the republic made a clear gain of one half. Still, however, so far as the pay of the soldiers was concerned, one <i>denarius</i> had always been given for every ten '<i>asses</i>' and that practice was prevalent until the state became dysfunctional. The impressions upon the coins of silver were two-horse and four-horse chariots, and hence it is that they received the names of '<i>bigatus, bigati</i>' and '<i>quadrigatus, quadrigati</i>'.[24] The '<i>as</i>' kept diminshing in its value so that during the Cicero's time (106—43 BC) the '<i>as</i>' had lost nearly all its value and the name '<i>as</i>' had entered into idioms, such as...</p>

<ol>

<h4>The Usage of '<i>as, assis</i>' in some of the Latin Idioms</h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Description</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Link</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>assem nullum dare</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">to not pay a penny / (lit.) to not give a dime</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Cic. Q. Rosc. 16:49): <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0013:text=Q.%20Rosc.:chapter=16&highlight=nullius%2Cnullum%2Cassem%2Cdedit">Cicero, For Quintus Roscius 16:49</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>ad assem omnia perdere</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">to lose everything to the last penny</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Hor. Ep. 2.2:27—28): <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2008.01.0539:book=2:poem=2&highlight=ad%2Cassem%2Cperdiderat">Q. Horatius Flaccus (Horace), Epistles 2.2:27—28</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>vilem redigi ad assem</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">to diminish in value and depreciate until worth only a worthless penny</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Hor. S. 1.1:43): <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0062&highlight=ad%2Cassem%2Cvilem%2Credigatur">Q. Horatius Flaccus (Horace), Satyrarum libri 1.1:43</a></td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

<p>...and a few centuries later, as described by Macrobius, these copper coins were being used as toys when kids on the street threw them in the air shouting 'capita' or 'navia' trying to guess the outcome beforehand.</p>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px"><h3>Footnotes</h3>

<!--

| | | | | |

| | ___ ___ | | _ __ ___ | | ___ ___

| / _ \ / _ | | ' \ / _ | / _ / |

| | | () | () | || | | | () | || /_

|_| _/ _/ _|| |_|_/ ___||___/ -->

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px">

<ol>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[1]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Németh 2013, 55—56; Rowan 2009, 7; Melville-Jones 1993, no. 657;</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=xalkismos&la=greek#lexicon">Χαλκισμός</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[2]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Ἰούλιος Πολυδεύκης Ναυκρατίτης a.k.a. Julius Pollux: <a href="https://archive.org/details/onomasticon01polluoft">Ὀνομαστικόν' (Onomasticon): Vol. IX, 118.</a> (Greek)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="https://archive.org/stream/onomasticon01polluoft/onomasticon01polluoft_djvu.txt">Full text of "Onomasticon"</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">Julius Pollux: <a href="https://ia902706.us.archive.org/27/items/pollucisonomasti02polluoft/pollucisonomasti02polluoft.pdf">Onomasticon: Vol. VI-X, Color</a> (Greek) (PDF, 17.1 MB)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">Julius Pollux: <a href="https://ia902706.us.archive.org/27/items/pollucisonomasti02polluoft/pollucisonomasti02polluoft_bw.pdf">Onomasticon: Vol. VI-X, BW</a> (Greek) (PDF, 13.1 MB)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="https://openlibrary.org/works/OL10686184W/Onomasticon">Onomasticon (10 editions) By Julius Pollux</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[3]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Németh 2013, 56; Rowan 2009, 7.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Macrobii Saturnalia Liber I: 7:19—24): Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (ca. AD 385/390—430), <a href="http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Saturnalia/1*.html">'Macrobii Theodosii (viri) Illustrissimi Saturnaliorum, Libri I' 7:19—24</a> (The Saturnalia, Book 1) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Ov. Fast. 1, 229—255): P. Ovidius Naso (43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Ov.%20Fast.%201.239&lang=original">'Fasti' 1:229—255</a> (The Festivals) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Aur. Vict. Orig. Gent. R. 3:1-7) Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), <a href="http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/victor_orig.html">'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:1-7</a> ...Incerti Auctoris... (Latin) <a href="http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/origo_01_trans.htm">Anonymous: On the Origin of the Roman People 3:1-7</a> (English) <a href="http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/victor.origio.html">alternative latin</a> (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[4]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Aur. Vict. Orig. Gent. R. 3:1-7) Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), <a href="http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/victor_orig.html">'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:1-7</a> ...Incerti Auctoris... (Latin) <a href="http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/origo_01_trans.htm">Anonymous: On the Origin of the Roman People 3:1-7</a> (English) <a href="http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/victor.origio.html">alternative latin</a> (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[5]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Aur. Vict. Orig. Gent. R. 3:1-7) Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), <a href="http://www.roman-emperors.org/origogentis.pdf">'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:1-7</a> ...Incerti Auctoris... Translated by Kyle Haniszewski, Lindsay Karas, Kevin Koch, Emily Parobek, Colin Pratt, and Brian Serwicki; Thomas M. Banchich, Supervisor; Canisius College Translated Texts, Number 3, Canisius College, Buffalo, New York 2004 (PDF, 422 KB) (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[6]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Ov. Fast. 1, 185—255): P. Ovidius Naso (43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid), <a href="https://ia800500.us.archive.org/6/items/ovidsfasti00oviduoft/ovidsfasti00oviduoft_bw.pdf">'Fasti' 1:185—255</a> (The Festivals) BW (PDF, 15.4 MB) (Latin and English) <a href="https://ia800500.us.archive.org/6/items/ovidsfasti00oviduoft/ovidsfasti00oviduoft.pdf">'Fasti' 1:185—255</a> (The Festivals) Color (PDF, 20.1 MB) (Latin and English)

<a href="https://archive.org/stream/ovidsfasti00oviduoft/ovidsfasti00oviduoft_djvu.txt">txt</a> (English)

<a href="http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/ovid/ovid.fasti1.shtml">alternative latin</a> (Latin)

<br /><ol><ol><ol>Sim. P. Ovidius Naso, <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Ov.+Fast.+1.185">'P. Ovidius Naso. Ovid's Fasti. Sir James George Frazer. London; Cambridge, MA. William Heinemann Ltd.'</a> Harvard University Press. 1933. (Latin)

</ol></ol></ol></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[7]</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=5329">St. Paulinus of Nola</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://our-catholic-faith.com/beings/saints/saint/st-paulinus-of-nola">St. Paulinus of Nola</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.ewtn.com/saintsHoly/saints/P/stpaulinusofnola.asp">St. Paulinus of Nola: Bishop and Writer</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[8]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Paul. Nol. Poëm. 32:65—77): Pontius Paulinus Nolanus (c. AD 353–431, a.k.a. Pontius Meropius Anicius Paulinus a.k.a. Paulinus of Nola), <a href="http://archive.org/stream/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog#page/n391/mode/2up/search/capita">'Corpus scriptorum ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, Vol 30' Carmen 32:65—77</a> A series of critical editions of the Latin Church Fathers, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1894. (<a href="https://ia801406.us.archive.org/14/items/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog.pdf">PDF</a>, 13.9 MB) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[9]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Németh 2013, 56; Rowan 2009, 7.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Paul. Nol. Poëm. 32:65—77): Pontius Paulinus Nolanus (c. AD 353–431, a.k.a. Pontius Meropius Anicius Paulinus a.k.a. Paulinus of Nola), <a href="http://archive.org/stream/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog#page/n391/mode/2up/search/capita">'Corpus scriptorum ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, Vol 30' Carmen 32:65—77</a> A series of critical editions of the Latin Church Fathers, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1894. (<a href="https://ia801406.us.archive.org/14/items/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog/corpusscriptoru25wiengoog.pdf">PDF</a>, 13.9 MB) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=capita&la=la#lexicon">Capita aut navia</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=navia&la=la#lexicon">Navia</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[10]</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=navia&la=la#lexicon">Navia</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[11]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Aur. Vict. Orig. Gent. R. 3:5) Author Unknown – Incerti Auctoris – Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. AD 320–390), <a href="http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/victor_orig.html">'Origo Gentis Romanae' (The Origins of the Roman People) 3:5</a> ...Incerti Auctoris... (Latin) <a href="http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/origo_01_trans.htm">Anonymous: On the Origin of the Roman People 3:5</a> (English) <a href="http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/victor.origio.html">alternative latin</a> (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[12]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (AD 354–430, a.k.a. Augustine of Hippo ), <a href="http://www.augustinus.it/latino/anima_origine/index2.htm">'De Anima et Eius Origine, Liber IV' (A Treatise on the Soul and Its Origin, Book IV) Chapter 20 [XIV]</a> called 'Quisnam sit interior videamus: utrum anima, an spiritus, an utrumque' (What kind of an inner man do we see: the soul, the spirit or both) (Latin) (<a href="http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf105.pdf">PDF</a>, 10 MB) (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="https://www3.nd.edu/~maritain/jmc/etext/homp098.htm">St. Augustine. His Life and Works</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[13]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (AD 354–430, a.k.a. Augustine of Hippo ), <a href="http://www.augustinus.it/latino/anima_origine/index2.htm">'De Anima et Eius Origine, Liber IV' (A Treatise on the Soul and Its Origin, Book IV) Chapter 20 [XIV]</a> called 'Quisnam sit interior videamus: utrum anima, an spiritus, an utrumque' (What kind of an inner man do we see: the soul, the spirit or both) (Latin) (<a href="http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf105.pdf">PDF</a>, 10 MB) (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="https://www3.nd.edu/~maritain/jmc/etext/homp098.htm">St. Augustine. His Life and Works</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Cic. Catil. 2.10.22–23) Marcus Tullius Cicero a.k.a. Κικέρων, (106–43 BC), <a href="https://ia601406.us.archive.org/14/items/mtulliciceronis19cicegoog/mtulliciceronis19cicegoog.pdf">'M. Tulli Ciceronis in L. Catilinam orationes quattuor': In L. Catilinam Oratio Secunda Habita Ad Populum 10.22–23</a> (The Second oration of Marcus Tullius Cicero against Lucius Catilina, Addressed to the People. 10.22–23) 1906 (PDF, 3 MB) (Latin) <a href="https://www.archive.org/stream/orationsofcicero00ciceuoft/orationsofcicero00ciceuoft_djvu.txt">The Orations of Cicero against Catiline</a> (txt) (Latin) <a href="http://latin.packhum.org/loc/474/13/1#1">alternative latin</a> (Latin)

<br /><ol><ol><ol>Sim. M. Tullius Cicero, <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0010%3Atext%3DCatil.%3Aspeech%3D2">'M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes: Recognovit brevique adnotatione critica instruxit Albertus Curtis Clark Collegii Reginae Socius.'</a> Albert Curtis Clark. Oxonii. e Typographeo Clarendoniano. 1908. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis.</a> (Latin)

<br /> For a translation, please see for example M. Tullius Cicero, <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0019%3Atext%3DCatil.%3Aspeech%3D2">'M. Tullius Cicero. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A.'</a> London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1856.</a> (English)

</ol></ol></ol></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[14]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Cic. Catil. 2.10.22–23) Marcus Tullius Cicero a.k.a. Κικέρων, (106–43 BC), <a href="https://ia601406.us.archive.org/14/items/mtulliciceronis19cicegoog/mtulliciceronis19cicegoog.pdf">'M. Tulli Ciceronis in L. Catilinam orationes quattuor': In L. Catilinam Oratio Secunda Habita Ad Populum 10.22–23</a> (The Second oration of Marcus Tullius Cicero against Lucius Catilina, Addressed to the People. 10.22–23) 1906 (PDF, 3 MB) (Latin) <a href="https://www.archive.org/stream/orationsofcicero00ciceuoft/orationsofcicero00ciceuoft_djvu.txt">The Orations of Cicero against Catiline</a> (txt) (Latin) <a href="http://latin.packhum.org/loc/474/13/1#1">alternative latin</a> (Latin)

<br /><ol><ol><ol>Sim. M. Tullius Cicero, <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0010%3Atext%3DCatil.%3Aspeech%3D2">'M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes: Recognovit brevique adnotatione critica instruxit Albertus Curtis Clark Collegii Reginae Socius.'</a> Albert Curtis Clark. Oxonii. e Typographeo Clarendoniano. 1908. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis.</a> (Latin)

<br /> For a translation, please see for example M. Tullius Cicero, <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0019%3Atext%3DCatil.%3Aspeech%3D2">'M. Tullius Cicero. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A.'</a> London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1856.</a> (English)

</ol></ol></ol></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[15]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Németh 2013, 56; Rowan 2009, 7.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Macrobii Saturnalia Liber I: 7:19—22): Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (ca. AD 385/390—430), <a href="http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Saturnalia/1*.html">'Macrobii Theodosii (viri) Illustrissimi Saturnaliorum, Libri I' 7:19—22</a> (The Saturnalia, Book 1) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[16]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Macrobii Saturnalia Liber I: 7:19—22): Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (ca. AD 385/390—430), <a href="http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Saturnalia/1*.html">'Macrobii Theodosii (viri) Illustrissimi Saturnaliorum, Libri I' 7:19—22</a> (The Saturnalia, Book 1) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[17]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Macrobii Saturnalia Liber I: 7:19—24): Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (ca. AD 385/390—430), <a href="http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Macrobius/Saturnalia/1*.html">'Macrobii Theodosii (viri) Illustrissimi Saturnaliorum, Libri I' 7:19—24</a> (The Saturnalia, Book 1) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Ov. Fast. 1, 235—255): P. Ovidius Naso (43 BC – AD 18), a.k.a. Ovid), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Ov.%20Fast.%201.239&lang=original">'Fasti' 1:235—255</a> (The Festivals) (Latin)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 33.13): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:33.13">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 33.13</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=33:chapter=13">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 18.3): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:18.3">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 18.3</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=18:chapter=3">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[18]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">Usher 2009, 488;</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.bestofsicily.com/mag/art231.htm">Timaeus of Taormina</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 33.13): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:33.13">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 33.13</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=33:chapter=13">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 18.3): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:18.3">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 18.3</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=18:chapter=3">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[19]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">From 'pecus, pecoris': a sheep, a goat or cattle. For instance, Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), 'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 18.3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">Plinius 'Naturalis Historiae' 18.3: 'Pecunia ipsa a pecore appellabatur.'</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 18.3): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/Naturalis_Historia/Liber_XVIII">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 18.3</a> (Latin)

<br /><ol><ol><ol>Sim. Gaius Plinius Secundus (a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plin.+Nat.+18.3&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0138">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 18.3</a> (Latin) Teubner</ol></ol></ol></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 33.13): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:33.13">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 33.13</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=33:chapter=13">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[20]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">

<ol>

<h4>One <i>libra, librae:</i></h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Description</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Metric</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>British derived customary systems</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>libra, librae</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">a unit of measurement</td>

<td style="padding:6px">327.45 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">11.55046 oz</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 33.13): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:33.13">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 33.13</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=33:chapter=13">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[21]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">

<ol>

<h4>One <i>as, assis:</i></h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Period</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Metric</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>British derived customary systems</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Description</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>as, assis</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(original)</td>

<td style="padding:6px">327.45 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">11.55046 oz</td>

<td style="padding:6px">a coin ('<i>as librarius</i>') or a unit of measurement</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>as, assis</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(after the First Punic War)</td>

<td style="padding:6px">56.69905 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">2 oz</td>

<td style="padding:6px">a coin or a unit of measurement</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>as, assis</i></td>

<td style="padding:6px">(after the Second Punic War)</td>

<td style="padding:6px">28.34952 g</td>

<td style="padding:6px">1 oz</td>

<td style="padding:6px">a coin or a unit of measurement</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td></td>

<td style="padding:6px">

<ol>

<h4>One '<i>as</i>' was divided, for instance:</h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Name</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Value</strong></td>

<td style="padding:6px"><strong>Decimal</strong></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>deunx</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">11/12</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 91.7 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>dextans</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">5/6</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 83.3 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>dodrans</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">3/4</td>

<td style="padding:6px">75 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>bes</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">2/3</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 66.7 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>septunx</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">7/12</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 58.3 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>semis</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">1/2</td>

<td style="padding:6px">50 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>quicunx</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">5/12</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 41.7 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>triens</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">1/3</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 33.3 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>quadrans</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">1/4</td>

<td style="padding:6px">25 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>sextans</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">1/6</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 16.7 %</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>uncia</i></td>

<td align="center" style="padding:6px">1/12</td>

<td style="padding:6px">≈ 8.3 %</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[22]</td>

<td style="padding:6px">(Plin. Nat. 33.13): Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23—79, a.k.a. Pliny the Elder), <a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:33.13">'Naturalis Historiae' (The Natural History) 33.13</a> The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. (English)

<br /><a href="http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=33:chapter=13">alternative link</a> (English)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[23]</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>Ibid.</i></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">[24]</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><i>Ibid.</i></td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px">Bibliography

<!--

| _ () | | () | |

| |) || |__ | |_ ___ __ _ _ __ __ _ _ __ | |__ _ _

| _ <| | '_ | | |/ _ \ / | '__/ _ | ' | '_ | | | |

| |) | | |) | | | () | (| | | | (| | |) | | | | || |

|/||.__/|||___/ _, || _,| .__/|| ||_, |

/ | | | / |

|/ || |_/ -->

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th></th>

<td style="padding:6px">

<ol>

<h4>Bibliography:</h4>

<p>

<table>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">Melville-Jones, John (1993):</td>

<td style="padding:6px">'Testimonia Numaria: Greek and Latin texts concerning ancient Greek coinage' Vol 1: Texts and Translations (London).</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">Németh, György (2013):</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258434610_COINS_IN_WATER">Coins In Water</a> ACTA CLASSICA UNIV. SCIENT. DEBRECEN. XLIX., pp. 55–63.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">Rowan, Clare (2009):</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.numismatics.org.au/pdfjournal/Vol20/Vol%2020%20Article%201.pdf">Slipping out of circulation: the after-life of coins in the Roman World</a> Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia Vol. 20, pp. 3–14.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">Teitel, Stephen:</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~stte/phy104-F00/notes-2.html">Theory of Probability</a></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style="padding:6px">Usher, Stephen (2009):</td>

<td style="padding:6px"><a href="http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/1301/1381">Oratio Recta and Oratio Obliqua in Polybius</a> Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 49, pp. 487—514</td>

</tr>

</table>

</p>

</ol>

</td>

</tr>

|