- Implement and analyze sort algorithms.

- Use a heap to implement a PriorityQueue.

- Use a PriorityQueue to find the top elements in a large dataset.

- Analyze the space needs of algorithms.

Computer science departments have an unhealthy obsession with sort algorithms. Based on the amount of time CS students spend on the topic, you would think that choosing sort algorithms is the cornerstone of modern software engineering. Of course, the reality is that software developers can go years, or entire careers, without thinking about how sorting works. For almost all applications, they use whatever general-purpose algorithm is provided by the language or libraries they use. And usually that's just fine.

So if you skip this lab and learn nothing about sort algorithms, you can still be an excellent developer. But there are a few reasons you might want to do it anyway:

-

Although there are general-purpose algorithms that work well for the vast majority of applications, there are two special-purpose algorithms you might need to know about: radix sort and bounded heap sort.

-

One sort algorithm, merge sort, makes an excellent teaching example because it demonstrates an important and useful strategy for algorithm design, called "divide-conquer-glue". Also, when we analyze its performance, you will learn about an order of growth we have not seen before. Finally, some of the most widely-used algorithms are hybrids that include elements of merge sort.

-

One other reason to learn about sort algorithms is that technical interviewers love to ask about them. If you want to get hired, it helps if you can demonstrate CS cultural literacy.

So, in this lab we'll analyze insertion sort, you will implement merge sort, we'll tell you about radix sort, and you will write a simple version of a bounded heap sort.

We'll start with insertion sort, mostly because it is simple to describe and implement. It is not very efficient, but it has some redeeming qualities, as we'll see.

Rather than explain the algorithm here, we suggest you read the insertion sort Wikipedia page, which includes pseudocode and animated examples. Come back when you get the general idea.

Here's our implementation of insertion sort in Java:

public class ListSorter<T> {

public void insertionSort(List<T> list, Comparator<T> comparator) {

for (int i=1; i < list.size(); i++) {

T elt_i = list.get(i);

int j = i;

while (j > 0) {

T elt_j = list.get(j-1);

if (comparator.compare(elt_i, elt_j) >= 0) {

break;

}

list.set(j, elt_j);

j--;

}

list.set(j, elt_i);

}

}

}We define a class, ListSorter, as a container for sort algorithms. By using the type parameter, T, we can write methods that work on lists containing any object type.

insertionSort takes two parameters, a List of any kind and a Comparator that knows how to compare type T objects. It sorts the list "in place", which means it modifies the existing list and does not have to allocate any new space.

This example shows how to call this function with a List of Integer:

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(3, 5, 1, 4, 2));

Comparator<Integer> comparator = new Comparator<Integer>() {

@Override

public int compare(Integer n, Integer m) {

return n.compareTo(m);

}

};

ListSorter<Integer> sorter = new ListSorter<Integer>();

sorter.insertionSort(list, comparator);

System.out.println(list);insertionSort, has two nested loops, so you might guess that its runtime is quadratic. In this case, that turns out to be correct, but before you jump to that conclusion, you have to check that the number of times each loop runs is proportional to n, the size of the array.

The outer loop iterates from 1 to n, so it is clearly linear. The inner loop iterates from i to 0, so it is also linear, and the total number of times the inner loop runs is quadratic.

If you are not sure about that, here's the argument:

-

The first time through,

i=1and the inner loop runs at most once. -

The second time,

i=2and the inner loop runs at most twice. -

The last time,

i=n-1and the inner loop runs at mostn-1times.

So the total number of times the inner loop runs is the sum of the series 1, 2, ... n-1, which is n (n-1) / 2. And the leading term of that expression (the one with the highest exponent) is n<sup>2</sup>.

In the worst case, insertion sort is quadratic. However:

-

If the elements are already sorted, or nearly so, insertion sort is linear. Specifically, if each element is no more than

klocations away from where it should be, the inner loop never runs more thanktimes, and the total runtime isO(kn). -

Because the implementation is simple, the overhead is low; that is, even if the runtime is

a n<sup>2</sup>, the coefficient of the leading term,a, is probably small.

So if we know that the array is nearly sorted, or is not very big, insertion sort might not be a bad choice. But for large arrays, we can do better. In fact, much better.

Merge sort is one of several algorithms whose runtime is better than quadratic (we're still not saying how much better). Again, rather than explaining the algorithm here, we suggest you read about it on Wikipedia. Once you get the idea, come back and you can test your understanding by writing your own implementation.

When you check out the repository for this lab, you should find a file structure similar to what you saw in previous labs. The top level directory contains CONTRIBUTING.md, LICENSE.md, README.md, and the directory with the code for this lab, javacs-lab13.

In the subdirectory javacs-lab12/src/com/flatironschool/javacs you'll find the source files for this lab:

-

ListSorter.java, -

ListSorterTest.java,

Run ant build to compile the source files, then run ant test to run ListSorterTest. As usual, it should fail, because you have work to do.

In ListSorter.java, we've provided an outline of two methods, mergeSortInPlace and mergeSort:

public void mergeSortInPlace(List<T> list, Comparator<T> comparator) {

List<T> sorted = mergeSortHelper(list, comparator);

list.clear();

list.addAll(sorted);

}

private List<T> mergeSort(List<T> list, Comparator<T> comparator) {

// TODO: fill this in!

return null;

}These two methods do the same thing but provide different interfaces. mergeSort takes a list and returns a new list with the same elements sorted in ascending order. mergeSortInPlace is a void method that modifies an existing list.

Your job is to fill in mergeSort. Before you write a fully recursive version of merge sort, start with something like this:

-

Split the list in half.

-

Sort the halves using

Collections.sortorinsertionSort. -

Merge the sorted halves into a complete sorted list.

This will give you a chance to debug the merge code without dealing with the complexity of a recursive method.

Next, add a base case. If you are given a list with only one element, you could return it immediately, since it is already sorted, sort of. Or if the length of the list is below some threshold, you could sort it using Collections.sort or insertionSort. Test the base case before you proceed.

Finally, modify your solution so it makes two recursive calls to sort the halves of the array. When you get it working, testMergeSort and testMergeSortInPlace should pass.

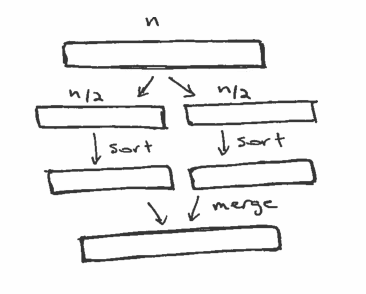

To classify the runtime of merge sort, it helps to think about the algorithm in terms of levels of recursion and how much work is done on each level. Suppose we start with a list that contains n elements. Here are the steps of the algorithm:

-

Make two new arrays and copy half of the elements into each.

-

Sort the two halves.

-

Merge the halves.

The following figure shows these steps.

The first step copies each of the elements once, so it is linear. The third step also copies each element once, so it is also linear. Now we need to figure out the complexity of step 2. To do that, it helps to looks at a different picture of the computation, which shows the levels of recursion:

At the top level, we have 1 list with n elements. At the next level there are 2 lists with n/2 elements. Then 4 lists with n/4 elements, and so on until we get to n lists with 1 element.

On every level we have a total of n elements. On the way down, we have to split the arrays in half, which takes time proportional to n on every level. On the way back up, we have to merge a total of n elements, which is also linear.

If the number of levels is h, the total amount of work for the algorithm is O(nh). So how many levels are there? There are two ways to think about that:

-

How many times do we have to cut

nin half to get to 1. Or, -

How many times do we have to double

1before we get ton.

Another way to ask the second question is "what power of 2 is n"?

2h = n

Taking the logn of both sides yields

h = log2 n

So the total time is O(n log n). I didn't bother to write the base of the logarithm because logarithms with different bases differ by a constant factor, so all logarithms are in the same order of growth.

Algorithms in O(n log n) are technically called "linearithmic", but most people just say "n log n".

It turns out that O(n log n) is the theoretical lower bound for sort algorithms that work by comparing elements to each other. That means there is no comparison sort whose order of growth is better than n log n. Nevertheless, there are non-comparison sorts that take linear time!

During the 2008 United States Presidential Campaign, candidate Barack Obama was asked to perform an impromptu algorithm analysis when he visited Google. Chief executive Eric Schmidt jokingly asked him for “the most efficient way to sort a million 32-bit integers.” Obama had apparently been tipped off, because he quickly replied, “I think the bubble sort would be the wrong way to go.” You can watch the video here.

Obama was right: bubble sort is conceptually simple but its runtime is quadratic; and even among quadratic sort algorithms, its performance is not very good.

The answer Schmidt was probably looking for is "radix sort", which is a non-comparison sort algorithm that works if the size of the elements is bounded, like a 32-bit integer or a 20-character string.

To see how this works, imagine you have a deck of cards where each card contains a 3-letter word. Here's how you could sort the cards:

-

Make one pass through the cards and divide them into buckets based on the first letter. So words starting with

ashould be together, followed by words starting withb, and so on. -

Divide each bucket again based on the second letter. So words starting with

aashould be together, followed by words starting withab, and so on. Of course, not all buckets will be full, but that's ok. -

Divide each bucket again based on the third letter.

At this point each bucket contains one element, and the buckets are sorted in ascending order. The following diagram shows an example with 3-letter words:

The top show shows the unsorted words. The second rows shows what the buckets look like after the first pass. The words in each bucket begin with the same letter.

After the second pass, the words in each bucket begin with the same two letters. After the third pass, there can be only one word in each bucket, and the buckets are in order.

During each pass, we iterate through the elements and add them to buckets. As long as the buckets allow addition in constant time, each pass is linear.

The number of passes, which we'll call w, depends on the length of the words, but it doesn't depend on the number of words, n. So the order of growth is O(wn), which is linear in n.

There are many variations on radix sort, and many ways to implement each one. You can read more about them here. As an optional exercise, consider writing a version of radix sort.

In addition to radix sort, which applies when the things you want to sort are bounded in size, there is one other special-purpose sorting algorithm you might encounter: bounded heap sort. Bounded heap sort is useful if you are working with a very large dataset and you want to report the "Top 10", or "Top k" for some value of k much smaller than n.

For example, suppose you are monitoring a Web service that handles a billion transactions per day. At the end of each day, you want to report the k biggest transactions (or slowest, or any other superlative). One option is to store all transactions, sort them at the end of the day, and select the top k. That would take time proportional to n log n, and it would be very slow because we probably can't fit a billion transactions in the memory of a single program. We would have to use an "out of core" sort algorithm. You can read about "external sorting" here.

Using a bounded heap, we can do much better! We'll explain how in three steps:

-

We'll explain (unbounded) heap sort.

-

You'll implement it.

-

We'll explain bounded heap sort and analyze it.

To understand heap sort, you have to understand a heap, which is a data structure similar to a binary search tree (BST). Here's the difference:

-

In a BST, every node,

x, has the "BST property": all nodes in the left subtree ofxare less thanxand all nodes in the right subtree are greater thanx. -

In a heap, every node,

x, has the "heap property": all nodes in both subtrees ofxare greater thanx.

The smallest element in a heap is always at the root, so we can find it in constant time. Adding and removing elements from a heap takes time proportional to the height of the tree h. And it is easy to keep a heap balanced, so h is proportional to log n. You can read more about heaps here.

The Java PriorityQueue is implemented using a heap. PriorityQueue provides the methods specified in the Queue interface, including offer and poll:

-

offer: Adds an element to the queue, updating the heap so that every node has the "heap property". Takeslog ntime. -

poll: Removes the smallest element in the queue from the root and updates the heap. Takeslog ntime.

Given a PriorityQueue, you can easily sort of a collection of n elements like this:

-

Add all elements of the collection to a

PriorityQueueusingoffer. -

Remove the elements from the queue using

polland add them to aList.

Because poll returns the smallest element remaining in the queue, the elements are added to the List in ascending order.

This way of sorting is called heap sort.

Adding n elements to the queue takes n log n time. So does removing n elements. So the run time for heap sort is O(n log n).

- In

ListSorter.javayou'll find the outline of a method calledheapSort. Fill it in and then runant testto confirm that it works.

A bounded heap is a heap that is limited to contain at most k elements. If you have n elements, you can keep track of the k largest elements like this:

For each element, x:

-

Branch 1: If the heap is not full, add

xto the heap. -

Branch 2: If the heap is full, compare

xto the smallest element in the heap. Ifxis smaller, it cannot be one of the largestkelements, so you can discard it. -

Branch 3: If the heap is full and

xis greater than the smallest element in the heap, remove the smallest element from the heap and addx.

Using a heap with the smallest element at the top, we can keep track of the largest k elements. Let's analyze the performance of this algorithm. For each element, we perform one of:

-

Branch 1: Adding an element to the heap is

O(log k). -

Branch 2: Finding the smallest element in the heap is

O(1). -

Branch 3: Removing the smallest element is

O(log k). Addingxis alsoO(log k).

In the worst case, if the elements appear in ascending order, we always run Branch 3. In that case, the total time to process n elements is O(n log k), which is linear in n.

- In

ListSorter.javayou'll find the outline of a method calledtopKthat takes aList, aComparator, and an integerk. It should return theklargest elements in theListin ascending order. Fill it in and then runant testto confirm that it works.

Until now we have talked a lot about runtime analysis, but for many algorithms we are also concerned about space.

For example, one of the drawbacks of merge sort is that it makes copies of the data. In our implementation, the total amount of space it allocates is O(n log n). With a more clever implementation, you can get the space requirement down to O(n).

In contrast, insertion sort doesn't copy the data because it sorts the elements in place. It uses temporary variables to compare two elements at a time, and it uses a few other local variables. But its space use doesn't depend on n.

Our implementation of heap sort creates a new PriorityQueue to store the elements, so the space is O(n); but if you are allowed to sort the list in place, you can run heap sort with O(1) space.

One of the benefits of the bounded heap algorithm you just implemented is that it only needs space proportional to k (the number of elements we want to keep), and k is often much smaller than n.

Software develpers tend to pay more attention to runtime than space, and for many applications, that's appropriate. But for large datasets, space can be just as important or more so. For example,

-

If a dataset doesn't fit into the memory of one program, the runtime often increases dramatically, or it might not run at all. If you choose an algorithm that needs less space, and that makes it possible to fit the computation into memory, it might run much faster. In the same vein, a program that uses less space might make better use of CPU caches and run faster.

-

On a server that runs many programs at the same time, if you can reduce the space needed for each program, you might be able to run more programs on the same server, which reduces hardware and energy costs.

So those are some reasons you should know at least a little bit about the space needs of algorithms.