Much has been written and said about the technical details of compact disc digital audio, but so far, I've found no public record 1 of anyone actually decoding the pits and lands on a compact disc to PCM samples. So I decided to do so. For an introduction on how compact discs work, I highly recommend the linked Wikipedia article and Technolgy Connection's video series.

There's a lot of secondary literature on compact disc digital audio,

but nothing's better than getting the information straight from the horses

mouth. In our case, this horse is called "IEC 60908 Audio recording –

Compact disc digital audio system". It's available for purchase from

several publishers at the totally reasonable price of just €345.

Fortunately someone uploaded it to

archive.org

, which is where such a fundamental standard belongs.

The PDF is bilingual with every other page being in french, but that's

noting that can't be fixed with poppler's pdfseparate and pdfunite.

Since we don't want to read the pits and lands from the disc with a microscope1, we need some kind of machine that converts them to some form that easier to process. Luckily such machines exist in the form of CD players, we just need to get directly to the electrical signal from the optical pickup that corresponds to pits and lands on the disc and ignore the fact that it already decodes everything.

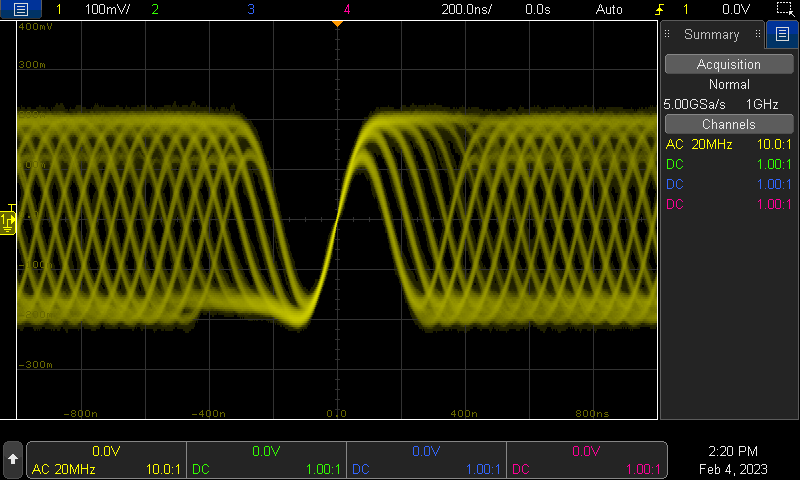

So I got hold of an old DVD player, put in an audio CD and started probing pins on the connector that connects the optical pickup to the main board. I quickly found a plausible-looking signal of about 300 mVpp amplitude.

For some reason, probably dust or scratches on the disc (see

later), the signal

sometimes drops out. To make my life easier, I captured a 4 MSa portion of

the signal without any dropouts at a rate of 20MSa/s2 and transferred it to my computer for

further analysis in python.

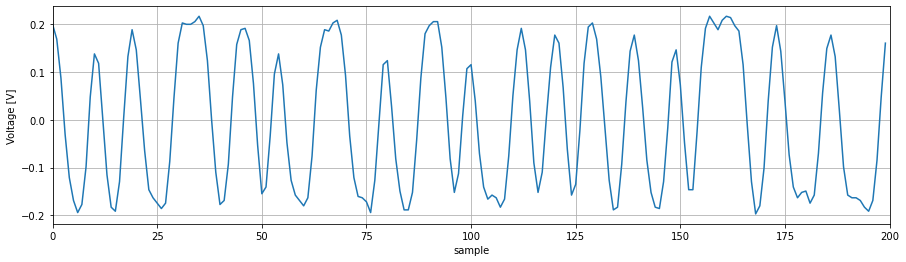

For reference, here's what the captured signal looks like, rendered using linear interpolation:

It's important to note that this signal isn't generated by an electronic circuit, but rather by the pits and lands flying past the pickup.

The signal captured from the pickup is an analog two-level signal that we need to convert to ones and zeros for further processing. It's tempting to just look at each sample individually and turn it into a '1' if it's > 0 and to a '0' if not. However, we lose some significant information that way since the exact voltage at the zero crossing carries sub-sample timing information that comes in handy for easier clock recovery as it reduces jitter. One lazy way around this is to interpolate the acquired samples and then do the threshold detection.

I've found that linear interpolation gives comparable results to proper sinc interpolation, so that's what I went with. To avoid glitches, I added some hysteresis to the threshold detection. The interpolation ratio is 20.

The first step in decoding any kind of signal without an explicit clock is recovering the clock from the signal itself. This usually aided by some kind of line coding that ensures that there are only so many consecutive bits without a transition. In our case the line coding is Eight-to-fourteen modulation that maps one byte to 14 channel bits. It is then pressed onto the disc using NRZ-I (Non-return to zero inverted) encoding, that is a '1' is encoded as a transition and a '0' as no transition. The combination of these two encodings guarantees that there are no more than 11 and no less than 3 unchanging consecutive bits.

This means that when looking at the signal we can't assume that the shortest time between two transitions is one unit interval, instead it's three.

The usual way of recovering the clock from a signal with an embedded clock is by means of a phase-locked loop. While these are usually implemented in a mixed-signal circuit, implementing one in software can be surprisingly easy. In this instance, it can be seen as a discrete-time simulation that's clocked at 400 MHz, i.e. on every interpolated bit.

Same as with a hardware PLL we need three main components. VCO, phase detector and loop filter.

A simple way of implementing a VCO in software is by means of an Numerically-controlled oscillator. Since all we need is know when to sample the input signal, the phase-to-amplitude converter part of the NCO can be reduced to detecting if the accumulator has wrapped around.

The phase accumulator is as simple as adding the frequency tuning word to the accumulator modulo the accumulator size on every clock cycle :

acc = 0

last_acc = 0

ftw = 42

acc_size = 1000

for bit in all_bits :

if acc < last_acc :

# integrator has wrapped around, sample the input

last_acc = acc

acc = (acc+ftw)%acc_size # that's the actual NCOThe job of the phase detector is to convert the phase difference between the output of the VCO and the incoming data stream into a proportional voltage. With the VCO being an NCO, implementing the phase detector is as simple as sampling the value of the phase accumulator whenever the input signal changes. That way, the phase detector also keeps its output constant in the absence of transitions at the input. To keep the sampling point as far away from the input transitions as possible, we want the phase of the VCO to be 180° at the transitions.

last_bit = False

phase_delta = 0

for bit in all_bits :

if last_bit != bit :

phase_delta = (acc_size/2 - acc)

last_bit = bitTo smooth the output of the phase detector before feeding it into the VCO, we need some kind of low-pass filter. I went with the equivalent of a first order low pass since that's trivial to implement and turned out be good enough.

last_bit = False

phase_delta = 0

delta_filtered = 0

for bit in all_bits :

...

alpha = .005

delta_filtered = delta*alpha + delta_filtered*(1-alpha)

...Here's how it all looks connected:

I found it really instructive to discover that a PLL-based clock recovery can be implemented in about a dozen lines of Python or any other imperative language without the use of any high-level tools such as Simulink. Apart from that it's quite fascinating how little it takes to implement a system that exhibits complex dynamic behaviour. Contrast that to other code, where the same number of lines just adds a couple of buttons to a window or so and requires calling into thousands of lines of library code.

Anyone who has ever dealt with closed-loop feedback systems will tell you that debugging them can be really difficult since it's hard to separate cause from effect.

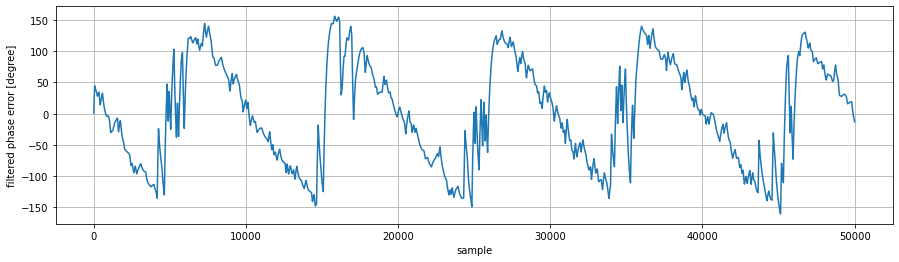

To get around this, we first operate our PLL open-loop by setting the loop gain to zero. It's also worth noting that a PLL with this kind of phase detector that's not sensitive to frequency will have a fairly tight lock range, which means that we need to get the VCO center frequency fairly close to its nominal frequency.

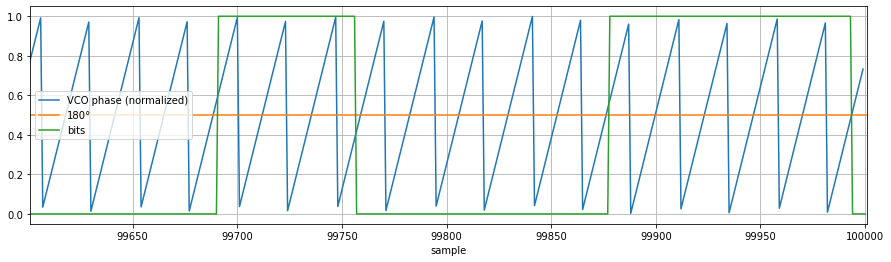

After playing with the center frequency of the VCO and the loop filter corner frequency this is what we get:

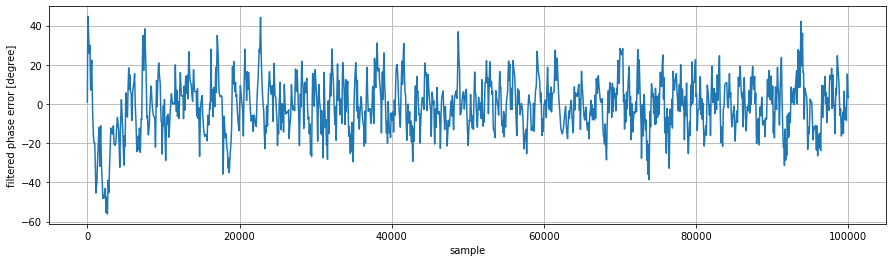

We can see that the phase detector outputs a sawtooth waveform which indicates that there's a frequency offset between the VCO and input frequency. Closing the loop by increasing the loop gain, the PLL locks and the phase error becomes constant. Why constant and not zero, you may ask? To bring the VCO to the correct frequency, its tuning voltage, i.e. the output of the phase detector and loop filter must be non-zero, resulting in a residual phase offset. We can eliminate that offset by introducing and integrator the loop so that we can get a zero phase detector output and non-zero tuning voltage. Tweaking the integrator gain, we get this:

The output of the phase detector being relatively close to zero indicates that our PLL is working as intended so we can move on to the next step, that is sampling the input signal with the recovered clock. As mentioned in the VCO section, this is as simple as capturing the value of the input signal every time the phase accumulator overflows.

sampled_bits = []

for bit in all_bits :

if acc < last_acc :

sampled_bits.append(bit)

...This leaves us with a stream of bits that we need to make sense of.

Here's another plot to verify that the clock recovery is working as it should:

We see that the VCO's phase is close to 180° when the input transitions and thus the phase wraparounds are as far from the edges as they can be.

Now that the clock recovery was working, I was curious to see how close to the actual frequency I need to get the VCO's initial frequency, i.e. what the PLL's lock range is. The correct frequency tuning word the locked PLL settles on is 42.6. The minimum initial frequency tuning word to achieve this is 41.6, the maximum is 43.9. This results in a lock range of about ±2.3%. I don't know if this is particularly good or bad for a PLL-based clock recovery.

As mentioned before, ones and zeros aren't encoded as-is on a CD, instead a '1' is econded as a transition and a '0' as no transition. This means it's insignificant whether a land on the disc is a high level or a low level. Decoding it is as simple as comparing each value to its predecessor:

nrz_bits = [a != b for a,b in zip(sampled_bits[1:], sampled_bits)]Data on a compact disc is structured as frames of 588 channel bits:

First, we have a 24 bit long sync pattern. The sync pattern has been chosen in such a way that it can't appear in valid data, so we can be absolutely sure to have found the start of a frame if we've seen the sync pattern.

To extract the frames from the bitstream, we do exactly this and write

the sync pattern as well as the following 588-24 = 564 channel bits to

a file for further decoding. The file contains each frame encoded as 588

1s and 0s per line.

The sync word is followed by the EFM-encoded control byte and 32 payload bytes, 24 of which are actual PCM samples and 8 of which are parity bytes. Each EFM-encoded byte is separated from its neighboring bytes by three merging bits to guarantee DC balance and meet the specified run length requirements. The actual value of the merging bits is irrelevant and isn't used in the decoding process.

See analyze.py for the implementation of all of this.

With the frames neatly put into a file we're now safely in the digital realm and can start to make sense of the data stored in them. Since the python code for this is much less interesting and magic than the clock recovery, there'll be fewer code snippets throughout this section.

Apart from the actual PCM samples, there's metadata in the form of subcode on the disc. We'll deal with this first since it's simpler to decode than the PCM samples and it's much easier to tell if we got it right.

This is the first time where we actually have to decode the eight-to-fourteen modulation. Decoding it is as simple as going through a lookup table that maps 14 bit words to 8 bit words. The contents of the lookup table are given as images in the standard. Too lazy to type thousands of ones and zeros, I OCR'd them using tesseract and massaged the resulting text into a lookup table that's read from the python script3.

The subcode is stored in a way that I found confusing at first: A CD contains 8 channels of subcode, one of which is actually interesting. Rather than storing the content of each subcode channel contiguously, The subcode byte in the frame carries 1 bit for each of the 8 subcode channels at once, so we get one bit for each subcode channel per frame.

The subcode itself also has some kind of framing structure, called blocks. Each block contains 96 payload bits. And is delimited by two 14-bit synchronization words S₀ and S₁ that don't map to anything the EFM LUT, so there's no ambiguity in finding the start of a block.

The first (P) subcode channel encodes the start of a track and is '0' for the remainder of the track. The second (Q) channel is the one that contains data we can make sense of.

All Q-channel blocks I decoded have the ADR bits set to 0001, meaning that the

DATA-Q bits are to be interpreted as Mode 1:

It's a bit odd that all numbers are BCD-encoded, I guess it was done that way so displaying them on a 7-segment display requires the least amount of logic.

- Track number: Current track on the Disc

- Index: Tracks can be subdivided by indices, but very few discs use this

- Min/Sec: Current run time of the track

- Frame: Each second is subdivided into 75 frames (This frame is different from the 588-bit channel frame)

Given that one frame of 588 channel bits contains 24 bytes of audio that make up 6 samples at a sample rate of 44.1 kHz, we get frames at a rate of 44.1kHz / 6 = 7350 frames/sec. Since it takes 98 frames to form a block, this results in a block rate of 44.1kHz / 6 / 98 = 75 Hz. This explains why each second is subdivided the way it is.

Decoding the data I captured, we get this:

Track 1.1 R=01:08:70 A=01:10:70

Track 1.1 R=01:08:71 A=01:10:71

Track 1.1 R=01:08:72 A=01:10:72

Track 1.1 R=01:08:73 A=01:10:73

Track 1.1 R=01:08:74 A=01:10:74

Track 1.1 R=01:09:00 A=01:11:00

Track 1.1 R=01:09:01 A=01:11:01

Track 1.1 R=01:09:02 A=01:11:02

Track 1.1 R=01:09:03 A=01:11:03

We can see that track number matches what was on the DVD player when I captured the waveform and that the frame number is incrementing as it should and wraps around at 75.

Looking good so far!

The only thing left to do is to check that the CRC is correct. The standard specifies the polynomial to be x¹⁶ + x¹² + x⁵ + 1 which is identical to the 16-bit CRC-CCITT and that the parity bits are stored inverted. Feeding the CONTROL, ADR, DATA-Q and inverted parity bits into the CRC should yield a zero CRC.

def calc_crc(bits) :

poly = 0x1021

crc = 0

for bit in bits :

if (crc>>15)&1 != bit :

crc = ((crc<<1)&0xffff) ^ poly

else :

crc = ((crc<<1)&0xffff)

return crcI was both surprised and relieved when the CRC did indeed turned out to be zero for all blocks, since I wouldn't have had much of an idea where to start debugging this other than staring at the code.

Successfully having decoded the Q-Channel subcode gave me the confidence that all of the previous steps, including OCR'ing the EFM LUT, were done correctly, so it's now time for the main event, the audio samples in glorious 16 bit linear PCM.

Revisiting the frame structure, we're now looking at the data and parity bytes:

Each frame contains 32 payload bytes, 24 of which are data and 8 of which are parity byes.

As every article on compact disc digital audio mentions, samples are encoded using Cross-interleaved reed-solomon coding (CIRC). The specification helpfully provides block diagrams of the encoder and decoder, which I've redrawn and put side-by-side for clarity:

Tracing each byte from input to output, we see that each byte is subject to the same delay of 111 frames, so the data stays as-is.

The important takeaway from the encoder block diagram is that the reed-solomon forward error correction (FEC) in the C₁ and C₂ encoders merely tacks on extra parity bytes and leaves the sample data as-is. That means we can focus on deinterleaving first and deal with the FEC later on.

Ignoring the FEC, the decoder is exactly the inverse of the encoder.

Based on that knowledge, we can substitute the C₁ and C₂ decoder boxes in the above block with pass-throughs as indicated by the dashed lines. This leaves us with having to implement the various delay and reordering elements.

I implemented the delay elements as a shift register encapsulated in a

class. Calling the step method returns the value from a prior

invocation, depending on n_delay.

class Delay:

def __init__(self, n_delay, fill = None) :

self.register = [fill]*n_delay

def step(self, v) :

if len(self.register) == 0 :

return v

r = self.register[-1]

self.register = [v] + self.register[:-1]

return r

d = Delay(3)

print(d.step(1)) # prints None

print(d.step(2)) # prints None

print(d.step(3)) # prints None

print(d.step(4)) # prints 1

print(d.step(5)) # prints 2

....For each column of delay stages, we create a list that has the individual delay elements:

first_delays = [Delay(0 if i%2 == 0 else 1, 0) for i in range(32)]Applying the delay to all input symbols then is as simple as zipping

them with the delay elements and calling step on each of them:

symbols_delayed1 = [d.step(x) for d,x in zip(first_delays, symbols_in)]The other delay columns work more or less identical apart from different delay values.

Right before the last delay columns, we need to shuffle the samples as indicated in the decoder diagram. Thanks to list comprehensions, that's a one-liner as well:

# output to input sample

deinterleave_tab = ( 0, 1, 6, 7, 16, 17, 22, 23, 2, 3, 8, 9, 18, 19, 24, 25, 4, 5, 10, 11, 20, 21, 26, 27)

symbols_deinterleaved = [symbols_delayed2[i] for i in deinterleave_tab]After this deinterleaving step, we get 24 bytes that form 6 consecutive stereo samples. All that's left to do is combine the bytes into the appropriate samples taking into account two's complement.

We then run this process for all frames and dump the samples into a wave file at 44.1 kHz sample rate, so we get something we can listen to. Even though we only got about 0.8 s of audio, it sounds plausible. To know if I got it all right, I ripped that particular track as an uncompressed wave file and imported it into Audacity. I aligned it to the decoded audio snippet with the help of the timestamps from the subcode and inverted it. Adding both tracks resulted in absolute silence, confirming that the decoded samples are indeed correct!

See decode.py for the implementation of all of this.

Remember that we initially captured 4 MSa at 20 MSa/s on the oscilloscope? This corresponds to a record length of 0.2 s. However, we got 0.78 seconds of audio. Since compact disc digital audio operates in real time, this is doesn't quite add up. The frequency tuning word from the PLL backs this up: The raw bit rate of a compact disc should be: 44.1 kHz / 6 samples per frame × 588 bits per frame = 4.3218 MBit/s. However, the bit rate as per the VCO frequency is 42.6 / 1000 × 20 MSa/s × 20 = 17.04 MBit/s. Multiplying this by the ratio between the oscilloscope record length and the length of the decoded audio, we get: 17.04 MBit/s × (0.2 s / 0.78 s) = 4.33 MBit/s, which is fairly close to the expected bit rate, so at least that that checks out.

All of this didn't quite make sense at first. If the DVD player is reading the disc about 4× faster than it needs to, where's that data going? Then I remembered the dropouts I initially saw on the oscilloscope. Maybe these dropouts aren't actually dust or scratches, but the DVD player too fast to and then jumping back on the disc to maintain the correct data rate on average?

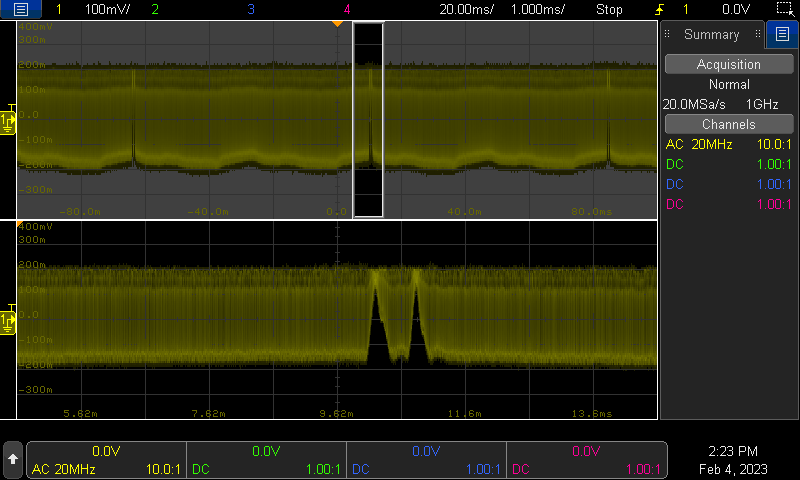

To find out if that's the case, I captured another portion of the waveform that has such a dropout:

At first attempt, the clock recovery PLL didn't relock after the first dropout and stayed unlocked thereafter. Looking at the PLL's signals, I found out that the integrator went off the rails during the dropout to the point where it was so far off that the PLL had no chance of ever locking again. Clamping the magnitude of the integrator value to slightly above its nominal value did the trick to get the PLL to relock after the dropouts.

With that obstacle out of the way we can decode the Q-Channel subcode as before:

[...]

Track 2.1 R=00:17:45 A=06:32:53

Track 2.1 R=00:17:46 A=06:32:54

Track 2.1 R=00:17:47 A=06:32:55

CRC error

Track 2.1 R=00:17:27 A=06:32:35

Track 2.1 R=00:17:28 A=06:32:36

Track 2.1 R=00:17:29 A=06:32:37

[...]

Track 2.1 R=00:17:45 A=06:32:53

Track 2.1 R=00:17:46 A=06:32:54

Track 2.1 R=00:17:47 A=06:32:55

CRC error

Track 2.1 R=00:17:27 A=06:32:35

Track 2.1 R=00:17:28 A=06:32:36

Track 2.1 R=00:17:29 A=06:32:37

[...]

Track 2.1 R=00:17:45 A=06:32:53

Track 2.1 R=00:17:46 A=06:32:54

Track 2.1 R=00:17:47 A=06:32:55

CRC error

Track 2.1 R=00:17:27 A=06:32:35

Track 2.1 R=00:17:28 A=06:32:36

Track 2.1 R=00:17:29 A=06:32:37

Based on time codes, we can see that the DVD player is indeed reading the same part of the disc multiple times. Suspicion confirmed!

My best guess for why the DVD player isn't reading the disc at the nominal rate is that the signal conditioning and clock recovery circuitry in the SoC can't handle the nominal rate since it also has to process the significantly faster signal from a DVD.

Decoding compact disc digital audio from the pickup signal to PCM samples was a really interesting project and was surprisingly easy after getting the clock recovery right and fixing a couple of stupid bugs in the deinterleaver. It's also worth noting that this project only required a digital oscilloscope with half-decent memory depth, a CD player and some basic DSP and bit shuffling knowledge, so I'm wondering why I haven't found much evidence of people having done this before.

One thing that I didn't cover is implementing the Reed-Solomon decoder. That'll has to wait until I've developed a better understanding of Reed-Solomon forward error correction.

Footnotes

-

While writing this article, a friend of mine pointed me to this post where someone did just that! ↩ ↩2

-

In the process of implementing the clock recovery, I was scratching my head why I was seeing lots of jitter on the acquired signal. Turns out that Keysight InfiniiVision oscilloscopes by default randomize the the time between samples at low sample rates to prevent aliasing. Turning off the antialiasing option in the display menu indeed fixed the problem. Another thing worth mentioning is that one needs to press the single shot button to get maximum memory depth on this series of oscilloscopes. Just pressing stop only yields half the memory depth. ↩

-

Only later I discovered that the freely available ECMA-130 Standard for CD-ROM includes a textual representation of the EFM LUT. ↩