- Requirement nesting is no longer supported. Requirements are supposed to be atomic components of a system, and by definition, atomic components cannot contain other atomic components and still be atomic. Recommendation is to migrate to our supported patterns.

Format-Callstack, the formatter for nested Requirements, is no longer supported. Recommendation is to migrate toFormat-Verbose.Nameis no longer a supported property on Requirements. Recommendation is to migrate to namespaces.

Requirements is a PowerShell Gallery module for declaratively describing a system as a set of "requirements", then idempotently setting each requirement to its desired state.

The background motivation and implementation design are discussed in detail in Declarative Idempotency.

Trevor Sullivan provides a good overview and (slightly outdated) tutorial video about Requirements.

A "Requirement" is a single atomic component of a system configuration. For a system to be in its desired state, all Requirements in the system must be in a desired state.

A Requirement is an object defined by three properties:

Describe- Astringthat describes the desired state of the Requirement.Test- Ascriptblockthat returns whether the Requirement is in its desired state.Set- Ascriptblockthat can be run to put the Requirement into its desired state if it is not in a desired state.

In DevOps, you may be managing a fleet of servers, containers, cloud resources, files on disk, or many other kinds of components in a heterogeneous system. Lets say you have n components in your system and every component is either in a GOOD or BAD state. You have two options:

- You can try and account for every possible configuration of your system and transition between those states, but then you will have 2**n possible states to manage.

- You can only account for the desired state of each individual component, so you will only have n states to account for. Much simpler!

If you only manage cloud resources, then try to use Terraform, ARM, or CloudFormation. If you only manage kubernetes resources, then try and use Helm. These are domain-specific frameworks for managing the desired state of resources and are best suited for their task.

However, you will often find you have complex configurations, such as configurations that can only be described in PowerShell. You may even have macroconfigurations that consist of one or more Terraform templates. In this case you will probably want something more generic to glue your configurations together without sacrificing the declarative desired state paradigm. This is where Requirements comes in.

Desired State Configurations allow you to declaratively describe a configuration, then let the local configuration manager handle with setting the configuration to its desired state. This pattern from the outside may seem similar to Requirements, but there are crucial differences.

DSC is optimized for handling many configurations asynchronously. For example, applying a configuration in parallel to multiple nodes. In contrast, Requirements applies a single configuration synchronously. This enables usage in different scenarios, including:

- CI/CD scripts

- CLIs

- Dockerfiles

- Linux

While Requirements supports DSC resources, it does not have a hard dependency on DSC's configuration manager, so if your Requirements do not include DSC resources they will work on any platform that PowerShell Core supports.

The easiest way to declare a requirement is to define it as a hashtable and let PowerShell's implicit casting handle the rest.

$requirements = @(

@{

Describe = "Resource 1 is present in the system"

Test = { $mySystem -contains 1 }

Set = {

$mySystem.Add(1) | Out-Null

Start-Sleep 1

}

},

@{

Describe = "Resource 2 is present in the system"

Test = { $mySystem -contains 2 }

Set = {

$mySystem.Add(2) | Out-Null

Start-Sleep 1

}

},

@{

Describe = "Resource 3 is present in the system"

Test = { $mySystem -contains 3 }

Set = {

$mySystem.Add(3) | Out-Null

Start-Sleep 1

}

}

)Our Describe describes the desired state of the Requirement (ex: "Resource 1 is present in the system") and not the Set block's transitioning action (ex: "Adding Resource 1 to the system"). This is because the Set block is not called if the Requirement is already in its desired state, so if we used the latter Describe and Resource 1 was already present in the system, we would be inaccurately logging that the Requirement is modifying the system when it is actually taking no action.

The sooner you embrace the Desired State mindset, the less friction you will have writing Requirements and managing your complex system configurations.

Once you have an array of Requirements, you can simply pipe the Requirements into Invoke-Requirement to put each Requirement into its desired state.

$requirements | Invoke-RequirementThe status of each Requirement will be logged to the output stream. By default they are shown with Format-List, but you can pipe the results to Format-Table, or use one of the packaged formatters for Requirements-specific event formatting and filtering.

As you learned previously, Requirements consist of Describe, Test, and Set properties. There are 4 types of Requirements--one for every permutation of including or excluding Test and Set. Note that Describe must always be present.

This is the kind you are already familiar with. It includes both a Test and Set.

If you wish to assert that a precondition is met before continuing, you can leave out the Set block. This is useful for Defensive programming, or when a Requirement requires manual steps.

@{

Describe = "Azure CLI is authenticated"

Test = { az account }

}Sometimes, your Set block is already idempotent and an associated Test block cannot be defined. In this case, you can leave out the Test block.

@{

Describe = "Initial state of system is backed up"

Set = { Get-StateOfSystem | Out-File "$BackupContainer/$(Get-Date -Format 'yyyyMMddhhmmss').log" }

}Some people have trouble managing large configurations with Requirements because they try and explicitly define a single array literal of Requirements; however, this is unnecessary and Requirements can be handled like any other PowerShell object. Here are some examples of patterns for managing Requirements.

Requirements should strongly avoid maintaining internal state. Requirements is for enforcing declarative programming, whereas maintaining state is an imperative loophole that breaks the declarative paradigm.

Instead, use selectors to easily derive up-to-date properties of the system using unit-testable functions.

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Gets the random storage account name from the environment in the cloud

#>

function Select-StorageAccountName([string]$EnvName) { ... }

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Returns a Requirement that ensures a storage ccount exists in Azure

#>

function New-StorageAccountRequirement {

@{

Describe = "Storage Account exists"

Test = { Test-StorageAccountExists (Select-StorageAccountName $env:EnvName) }

Set = { New-StorageAccount (Select-StorageAccountName $env:EnvName) }

}

}You can wrap Requirements in a parameterized function or script to avoid redifining Requirements--

function New-ResourceGroupRequirement {

Param(

[string]$Name,

[string]$Location

)

New-RequirementGroup "rg" -ScriptBlock {

@{

Describe = "Logged in to Azure"

Test = { Get-AzAccount }

Set = { Connect-AzAccount }

}

@{

Describe = "Resource Group '$Name' exists"

Test = { Get-AzResourceGroup -Name $Name -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue }

Set = { New-AzResourceGroup -Name $Name -Location $Location }

}

}

}Then call your function to generate the Requirement--

$Name = "my-rg"

$Location = "West US 2"

& {

New-ResourceGroupRequirement -Name $Name -Location $Location

@{

Describe = "Do something with the resource group"

Test = { ... }

Set = { ... }

}

} `

| Invoke-Requirement `

| Format-TableUsing control flow statements, like if and foreach, can dramatically simplify your Requirement definitions. Let's see if we can simiplify our quickstart example.

foreach ($resourceId in 1..3) {

@{

Describe = "Resource $resourceId is present in the system"

Test = { $mySystem -contains $resourceId }.GetNewClosure()

Set = { $mySystem.Add($resourceId) | Out-Null; Start-Sleep 1 }.GetNewClosure()

}

}Notice that we had to call .GetNewClosure() to capture the current value of $resourceId in the scriptblock--otherwise the value would be 3 or $null depending on where we invoked it.

When you define Requirements with control flow in this manner, the Requirements are written to output. As such, this logic should be wrapped in a script, function, or scriptblock.

You can group Requirements into namespaces for clearer logging. To add a namespace to Requirements, use the New-RequirementGroup function. You can nest namespaces as well.

New-RequirementGroup "local" {

New-RequirementGroup "clis" {

@{

Describe = "az is installed"

Test = { ... }

Set = { ... }

}

@{

Describe = "kubectl is installed"

Test = { ... }

Set = { ... }

}

}

New-RequirementGroup "configs" {

@{

Describe = "cluster config is built"

Test = { ... }

Set = { ... }

}

}

}

New-RequirementGroup "cloud" {

@{

Describe = "Terraform is deployed"

Test = { ... }

Set = { ... }

}

}The above example would result in the Requirements below.

Namespace Describe

--------- --------

local:clis az is installed

local:clis kubectl is installed

local:configs cluster config is built

cloud Terraform is deployed

Isomorphic execution means that our Requirements are enforced the same regardless of what context they are enforced in. You will want your Requirements to run in a CICD pipeline for safe deployment practices and run manually from your local machine for development purposes, but in both contexts the Requirements should run exactly the same.

We will accomplish this by implementing Separation of Concerns, separating our Requirement definitions from our execution logic:

-

myrequirements.ps1, which will return an array of Requirements. -

Invoke-Verbose.ps1, which will be called in a CICD pipeline and write verbose status information to the output stream../myrequirements.ps1 | Invoke-Requirement | Format-Verbose

-

Invoke-Checklist.ps1, which will be called in a console and interactively write to the host../myrequirements.ps1 | Invoke-Requirement | Format-Checklist

If you're using Windows and PowerShell 5, you can use DSC resources with Requirements.

$requirement = @{

Describe = "My Dsc Requirement"

ResourceName = "File"

ModuleName = "PSDesiredStateConfiguration"

Property = @{

Contents = "Hello World"

DestinationPath = "C:\myFile.txt"

Force = $true

}

}

New-Requirement @requirement | Invoke-Requirement | Format-ChecklistInvoke-Requirement will output logging events for each step in a Requirement's execution lifecycle. You can capture these logs with Format-Table or Format-List, or

$requirements | Invoke-Requirement | Format-TableThese logs were using -Autosize parameter, which better formats the columns, but does not support outputting as a stream.

Method Lifecycle Name Date

------ --------- ---- ----

Test Start Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:25 PM

Test Stop Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:25 PM

Set Start Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:25 PM

Set Stop Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

Validate Start Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

Validate Stop Resource 1 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

Test Start Resource 2 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

Test Stop Resource 2 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

Set Start Resource 2 6/12/2019 12:00:26 PM

...

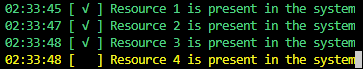

Format-Checklist will present a live-updating checklist to the user.

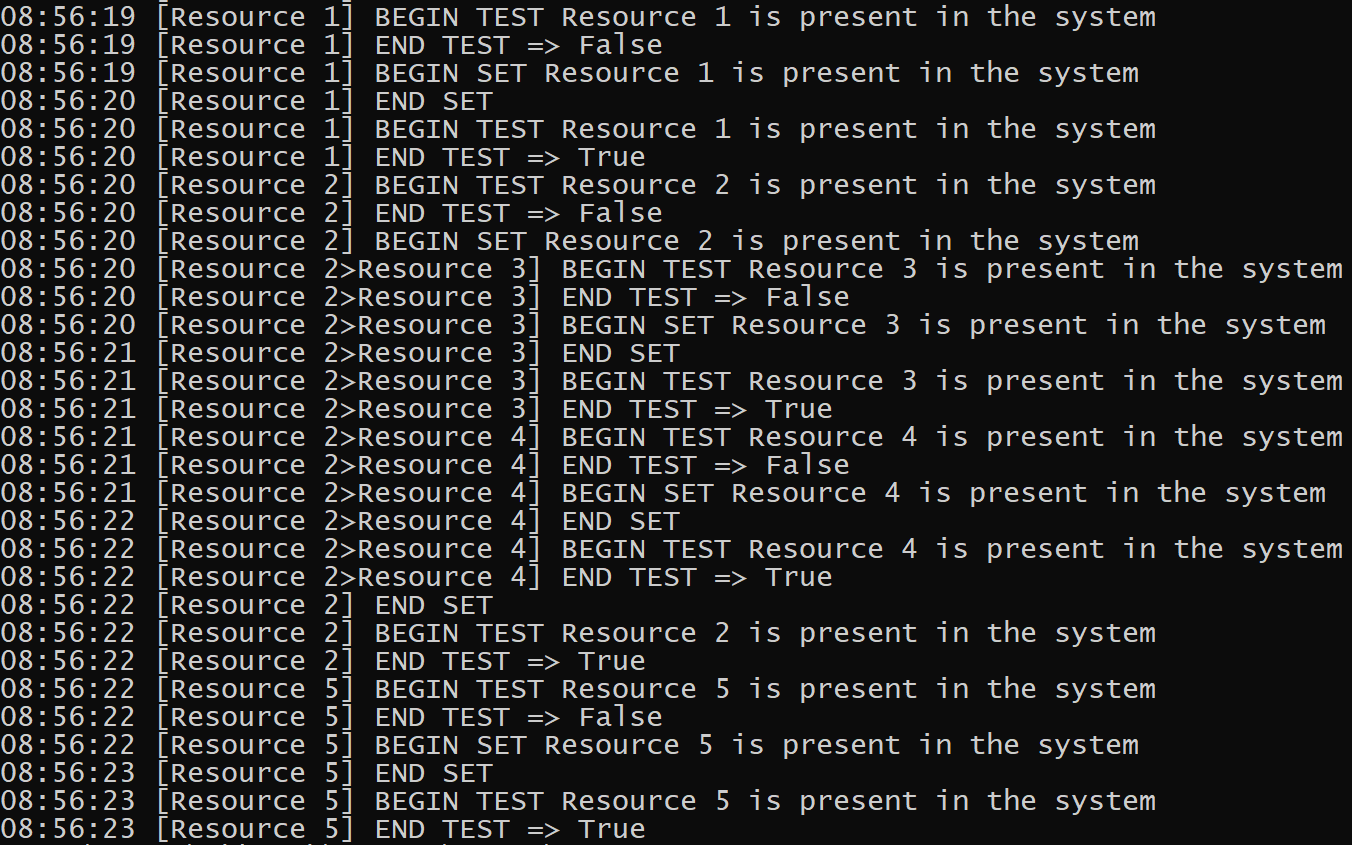

Unlike Format-Checklist, Format-Verbose prints all log events and includes metadata. For complex use cases, you can define nested Requirements (Requirements that contain more Requirements in their Set block). Format-Verbose will print the stack of Requirement names of each Requirement as its processed.

This project welcomes contributions and suggestions. Most contributions require you to agree to a Contributor License Agreement (CLA) declaring that you have the right to, and actually do, grant us the rights to use your contribution. For details, visit https://cla.microsoft.com.

When you submit a pull request, a CLA-bot will automatically determine whether you need to provide a CLA and decorate the PR appropriately (e.g., label, comment). Simply follow the instructions provided by the bot. You will only need to do this once across all repos using our CLA.

This project has adopted the Microsoft Open Source Code of Conduct. For more information see the Code of Conduct FAQ or contact opencode@microsoft.com with any additional questions or comments.