Define a Docker image that runs a Jupyter server. Next, create a Jupyter notebook by accessing Jupyter from the host machine. In Milestones 2 and 3, we will use this Jupyter notebook to explore the dataset and train the anomaly detection model.

- Running processes in Docker containers is a common practice in the industry for many reasons, including the portability and ease of sharing images, its ability to run almost everywhere, the isolation it provides, and because you can avoid installing dependencies on your machine.

- By defining, building, and running a Docker image, we’ll start to familiarize ourselves with some of the terms we will use in the project: for example, image and container.

- We will use the same Jupyter notebook we just created to analyze our dataset and train the model.

- We will create another Dockerfile to run the web service using a similar approach in a later milestone.

- Create a new directory and name it “liveProject.” This location is the working directory and is where we will develop our project.

- Within the directory, create a second directory and name it “jupyter.” Then, in the Jupyter directory, create a Dockerfile. This Dockerfile represents the image we will use to run Jupyter.

- In the Dockerfile, define as base a Python image. A smaller one like

python:3.7-slimshould suffice. Then, use theRUNinstruction with the commandmkdir srcto create a/srcdirectory inside the container. Use theWORKDIRinstruction to set/srcas the working directory. - In the Dockerfile, add another

RUNthat installs Jupyter using pip, which is the Python package installer. - Next, use the

CMDinstruction to specify the command that starts the Jupyter server.- Because we are inside a Docker container and we want to access Jupyter from the outside, we need to use the following options while starting the Jupyter server:

no-browserandallow-root. Besides this, I’d recommend using theipandportoptions to explicitly define the IP and port where the server will run. You could use the IP address0.0.0.0.

- Because we are inside a Docker container and we want to access Jupyter from the outside, we need to use the following options while starting the Jupyter server:

- After defining the Dockerfile, on the terminal, use Docker’s

buildcommand to build the image using the name{your_name}/lp-jupyter: for example,juan/lp-jupyter. - Run the Docker image using the publish or expose option (

-p) to forward the port you used in the secondCMDcommand to the local machine. The command that runs the Docker image is namedrun. This command will run the Docker image and start the Jupyter server. After running it, you will see on screen the address where Jupyter is running. Click on it to access it. - From Jupyter, create a new notebook and print “hello, world.”

Explore and visualize the dataset we will use to train the anomaly detector.

- Analyzing and visualizing a dataset is an essential step when working with data. With three visualizations, we will examine the shape of the training dataset and its details. Furthermore, we will discover that the data’s features are very far from resembling a bell-shaped, normal distribution and instead are skewed by many observations we could consider outliers. Armed with this knowledge, will be better prepared to fit a model using the data, which we will do in the next milestone.

- Besides visualizing the dataset, we will learn how to get a statistical summary of the data with the

describe()function. This function reports several statistical properties of the data, such as its mean and standard deviation values, quantiles, and count. - We will use Plotly, a visualization library, to interactively visualize the data. Out of the box, Plotly adds a widget on the plot with various controls for zooming in, resizing, autoscaling, panning, saving the image as a PNG file, and more. Besides this, without having to do extra work, a Plotly graph provides additional information, such as the data points’ values, box plot attributes (the fences and quantiles), and histogram bucket information by just hovering over them using the mouse. These values are useful data we can always examine when doing an exploratory data analysis.

Our project’s dataset is a sample of a real-life dataset obtained from the author’s organization, LOVOO, which is a dating and social application. This dataset presents two features related to the users’ spending patterns of the in-app currency (named credit) during a particular period. The first feature, mean, is the normalized average amount of credit a user has spent during that time while the second feature, sd, is the standard deviation (also normalized). During the dataset analysis, you will see that most values are concentrated in the same region while others are very far from the tendency. In some cases, these abnormal values are outliers or anomalies—users whose spending behaviors differ from the normality.

- Add the training (train.csv) and test (test.csv) datasets to the liveProject/jupyter/ directory from the previous milestone.

- Create a requirements.txt file and define the libraries we will use to analyze the dataset. Some of the libraries we need are pandas (to work with the dataset) and Plotly (to visualize it). Feel free to add others you might find convenient.

- In the same Dockerfile from Milestone 1, add a

COPYinstruction to copy requirements.txt into the working directory (see Milestone 1, step 3). Next, use theRUNinstruction to install the packages from requirements.txt. - Build the Docker image as we did in Milestone 1, step 6.

- Now, we will start the Jupyter service by using the same instruction from Milestone 1, step 7.

- On this occasion, because we want to use the datasets in the notebooks, we need to use a bind mount in the container. Quoting the official Docker documentation, “When you use a bind mount, a file or directory on the host machine is mounted into a container.” In other words, you will be able to access a directory of the host machine from within the Docker container. The directory we will mount, also known as the source, is the current directory liveProject/jupyter/ (the one containing the datasets and the Dockerfile). The target (the path in the container where we want to bind the source directory) is the container’s working directory (/src).

- To create it, use the

-vor--mountflag in thedocker runcommand.

- Once the server is running, go to Jupyter and create a new notebook named exploration.

- With the notebook up and running, import pandas and Plotly from the first cell. Then, use pandas to load both the training and test datasets into a pandas DataFrame. If the directory was correctly mounted, you should see both datasets in the list of files.

- Visualize and examine the dataset by doing the following:

- Use the DataFrame’s

head()method to print the dataset’s first five rows. Seeing a sample of the data is a practical way to get an idea of its shape, data types, and entries. If you wish to see more, change the n parameter to the desired number of rows. - Call the dataset’s

shapeattribute to print the dataset’s dimensionality. The output is a tuple of size two, where the first value is the DataFrame’s numbers of rows, and the second is the number of columns. - Use the method

describe()to calculate descriptive statistics for the dataset’s two features. This method prints a table containing each feature’s count (number of entries), mean value, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, and percentiles. These statistics summarize the data in terms of its central tendency and explain how dispersed it is. For example, the summary of the training set shows that the first feature’s minimum and maximum values are -0.284889 and 66.324763, and those of the second feature are -0.106749 and 57.676982, meaning that the first feature has a longer range than the second one. - With Plotly, draw a scatter plot where the x axis is the dataset’s mean feature and the y axis is the sd feature. Each point in the graph represents one data observation from the dataset. Similar to the statistical summary, a scatter plot is a tool for exploring a dataset and its characteristics. Even though it doesn’t give us precise values like the statistical summary, it allows us to visually and empirically test the data. For example, the training set’s scatter plot shows that most values are within the 0 to 10 range. If you hover over the data points using the mouse, you will see the data point’s value. For example, if you move the cursor over the right-most point, you will see that the mean feature value is 66.324, which should also be the maximum value for that feature as seen on the

describe()function’s output. - Use two histograms to visualize both features’ distributions with the parameter nbins set to 20. Due to very large values in both features, the distributions should look highly right skewed, meaning that many of its values are less than the mean. As a result, the plot’s peak is on the left end of the graph.

- Last, we draw two box plots (again, one per feature). A box plot is a visualization for representing the spread of the data and its quantiles. Its name is because it uses a box and two lines (known as whiskers), where the ends of the box mark the first (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), and the whiskers are the lower and upper limits. These lower and upper limits are calculated by their respective formulas:

Q1 – 1.5 * (Q3-Q1)andQ3 + 1.5 * (Q3-Q1). The values falling outside these limits are categorized as outliers. At a quick glance, the box plots show the outlier data points above the upper limit and a horizontal line instead of a box—this line is the box! But we see it flat instead of squared because the distance between Q3 and Q1 (known as the interquartile range) is extremely small compared to the large outlier values. However, because Plotly graphs are interactive, you can zoom in until the line starts to resemble a box. You can find an example of some of these visualizations in the “full solution” help layer.

- Use the DataFrame’s

- Save the notebook.

Train an anomaly detection model using the Isolation forest model. We also export the model and visualize its decision boundary.

- In this milestone, we will create an anomaly detection model, which we could consider the center and key component of the platform. Later, we will serve the model using a web service and generate metrics.

- Besides training the model, we will explore the concept of anomaly detection and one of its most popular algorithms, Isolation Forest. Regarding the algorithm itself, we quickly describe it and introduce one of its most crucial hyperparameters: contamination.

- While working with the model, we will also learn about the concept of a decision boundary and how to visualize it using the function decision_function() and Matplotlib.

Isolation Forest (Fei Tony Liu, Kai Ming Ting, and Zhi-Hua Zhou, 2008) is an unsupervised learning algorithm for identifying anomalies, or data observations that follow a different pattern than in normal instances. Unlike most anomaly detection algorithms, which work by learning the normal or common patterns and classifying the rest as anomalies, an isolation forest focuses on isolating the anomalies and not the normal cases. According to the authors, the drawback of the first approach is that these methods are optimized for profiling the normal instances and not the anomalies and their constraint to perform well in only low-dimensional data. On the other hand, isolation forests focus on the property that anomalies are usually the minority class among a dataset and that their features differ from the normal ones. As a result, and quoting the paper, “Anomalies are ‘few and different,’ which make[s] them more susceptible to isolation than normal points.”

By this point, we have executed the Docker run command at least three times; and that’s great because now we know how to use it. However, typing such a large and verbose command takes time, and it’s prone to errors. To streamline the process, I’d suggest using a makefile. A makefile is a building automation tool consisting of a file named makefile (without extension). This makefile consists of named rules that, upon executing them, execute a system command, like an alias. For example, we could have a rule named run whose system command is docker run -v $(PWD):/src -p 8888:8888 {your_name}/lp-jupyter. So instead of executing the Docker command, we could use make run. Shorter, right? The makefile file should look as follows:

run:

docker run -v $(PWD):/src -p 8888:8888 {your_name}/lp-jupyter

To use it, execute make run from the terminal while same in the path as the makefile.

- Picking up where we last left off (the liveProject/jupyter/ directory), add scikit-learn and Matplotlib to our list of requirements in requirements.txt.

- Build the Docker image.

- Start the Docker image as we did in Milestone 2, step 5, and access Jupyter. From Jupyter, create a new notebook and name it train.

- Our tasks in this milestone are loading the dataset, training the model, and visualizing its decision boundary. Therefore, in the notebook’s first cell, import pandas, NumPy, Matplotlib, and scikit-learn’s Isolation forest class.

- Load both the training and test datasets.

- Now, we will train the model.

- To train it, create an instance of an

IsolationForestmodel and use the parameterrandom_stateset to16for reproducibility purposes. You can find the model’s documentation atsklearn.ensemble.IsolationForest. Assigning this parameter ensures that we will all obtain the same results. Why 16? It’s just a random number; there’s no particular reason. - Use the method

model.fit()with the loaded training set as a parameter to train it. That’s it; we have the model. Wait, do we? Let’s take a look.

- To train it, create an instance of an

- Note: As we saw in the introduction, an isolation forest isolates the anomalous points from the non-anomalous points. In layman’s terms, we could say that it builds a frontier that separates these anomalous points from the non-anomalous points. This frontier is sometimes known as the decision boundary or decision function, and we can obtain it by using as a proxy the anomaly scores obtained with the method

model.decision_function()and the input samples. In the next step, we will visualize it. - Draw the model’s decision function.

- Drawing the boundary is not a trivial problem. Hence, here’s a snippet that does it (code was modified from an official scikit-learn example). But before you copy/paste, let’s quickly go through it and discuss it.

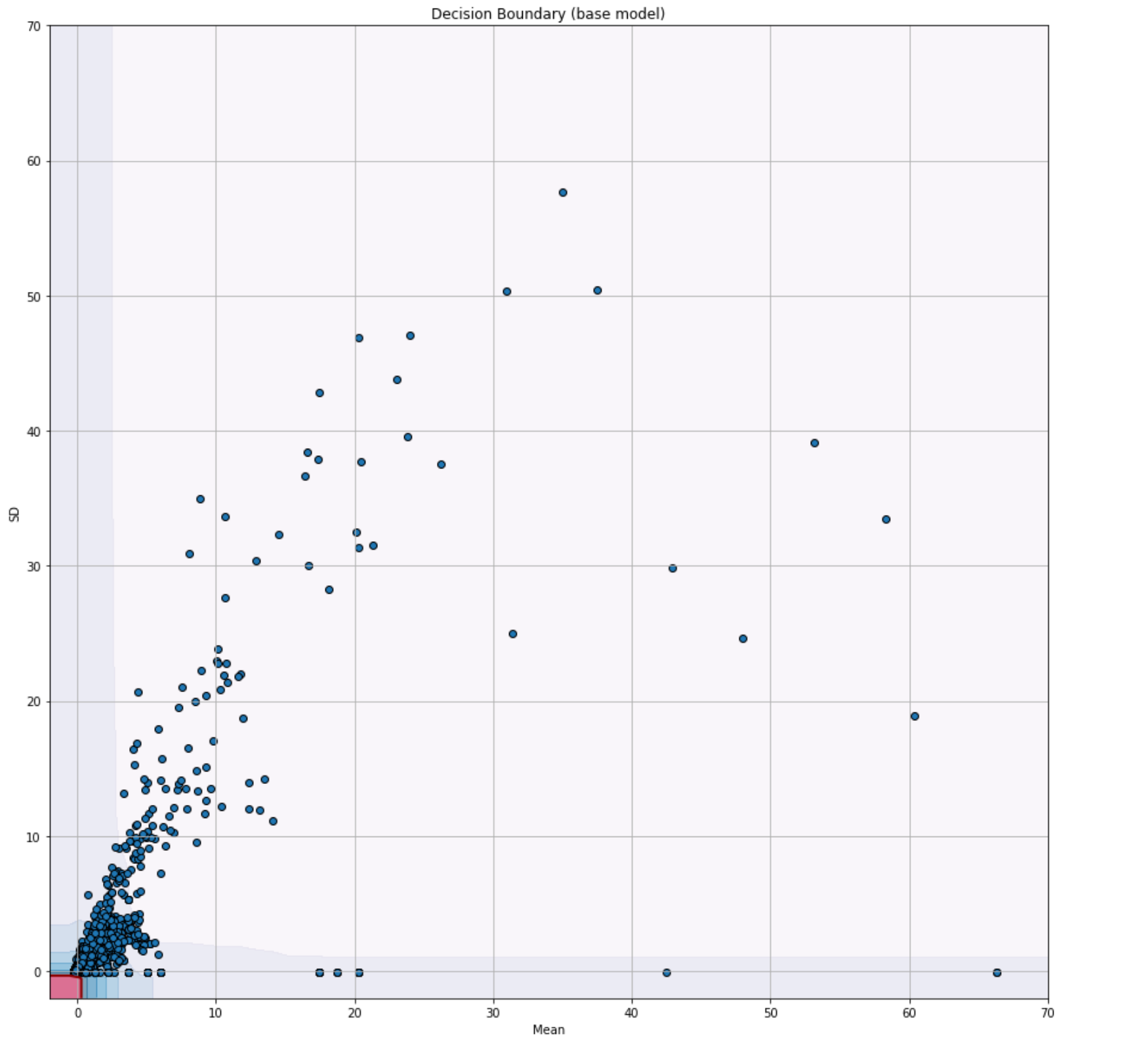

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Change the plot's size. plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = [15, 15] # Plot of the decision frontier xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-2, 70, 100), np.linspace(-2, 70, 100)) Z = clf.decision_function(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()]) Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape) plt.title("Decision Boundary (base model)") # This draw the "soft" or secondary boundaries. plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, levels=np.linspace(Z.min(), 0, 8), cmap=plt.cm.PuBu, alpha=0.5) # This draw the line that separates the hard from the soft boundaries. plt.contour(xx, yy, Z, levels=[0], linewidths=2, colors='darkred') # This draw the hard boundary plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, levels=[0, Z.max()], colors='palevioletred') plt.scatter(X_train.iloc[:, 0], X_train.iloc[:, 1], edgecolors='k') plt.xlabel('Mean') plt.ylabel('SD') plt.grid(True) plt.show()

- The main idea behind the visualization involves generating many points, covering the range of both features of the training set and predicting the anomaly scores of these generated points with the

decision_function()function (note that I named my model variableclf; yours might have a different name). After predicting, we draw the generated points using Matplotlib’s contour plot to see the “ripples” (the different boundary levels). After drawing it, you will see a “hard” boundary in red and “soft” boundaries in different shades of blue. Make sure you also add the training set (I named mineX_train; yours might have a different name) to the plot usingplt.scatter(). - Copy/paste the snippet above to draw the decision boundary. The image that follows shows how the plot should look.

- Let’s take this milestone step to interpret what we see here. The plot you have on screen is the decision boundary of the isolation forest. Everything within the red region is what I call the “hard” decision boundary. It contains the inliers, or normal points. The rest are the outliers, or anomalies. Here, we can barely see the red region; it is extremely small compared to the rest of the space. Yet, it contains most of the points (around 85%) of the training dataset. However, the remaining 15% is still a lot of data, and it is probable that many of these points are data points that aren’t extremely anomalous or points that might even be false positives. So, for this case, it would be wise to increase the decision boundary’s size, thus also reducing the points that would be classified as outliers. How? By using the contamination hyperparameter. See note 1 in the Notes section below.

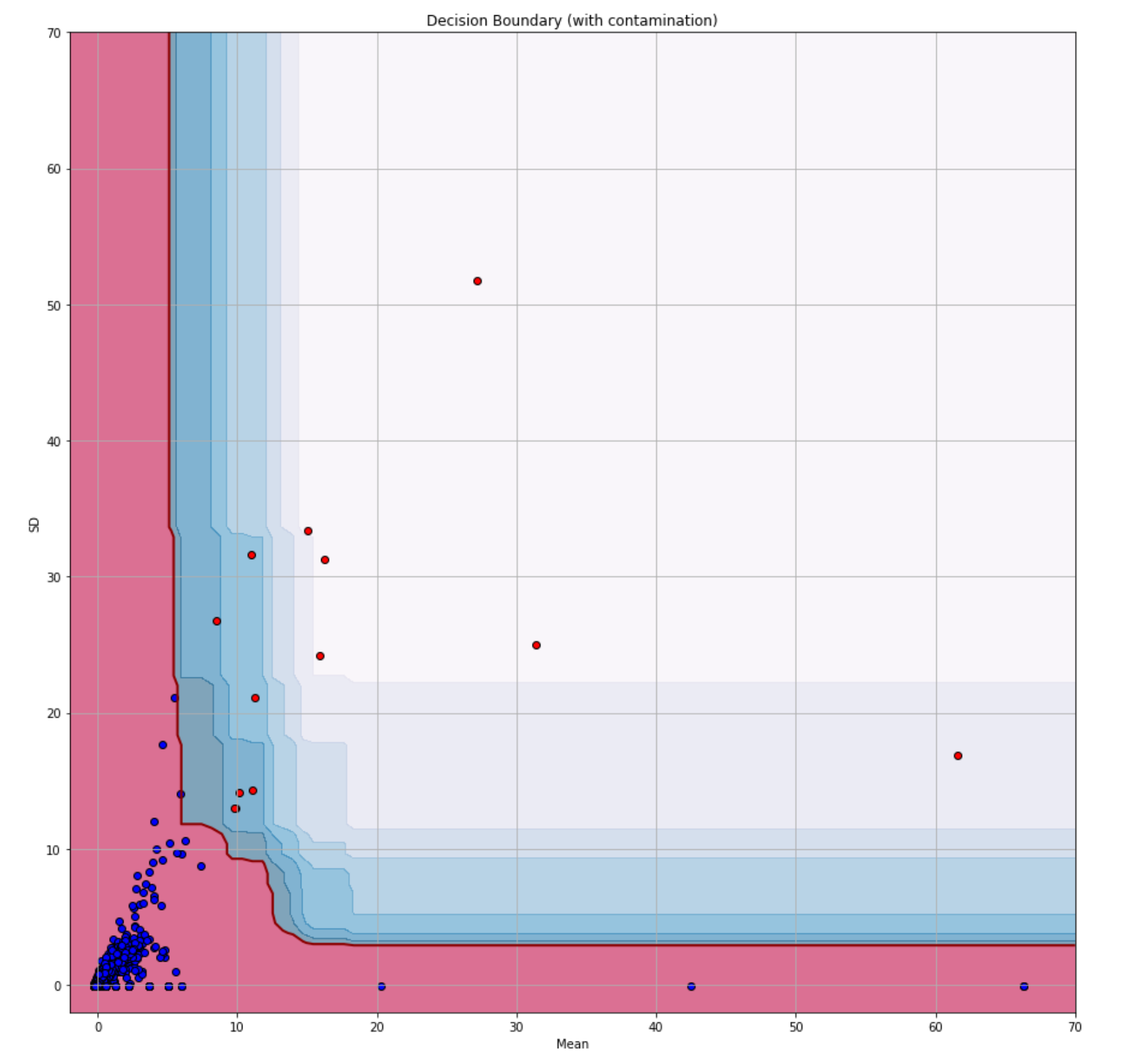

- Retrain the model using the

contaminationhyperparameter set to0.001. This hyperparameter controls the proportion of outliers in the dataset, so we will force the model to build its decision function with the constraint that only 0.1% of the data observations are outliers. With this hyperparameter, we will drastically reduce and control the outliers’ space. - Replot the decision boundary of the new model. Notice the difference? In this new model, the hard decision boundary covers more space than the previous one, leaving us with values that could be considered extremely anomalous.

- Use the model’s

predict()method to test it with the test dataset. The function returns an array with the predictions where each value is either -1 (outlier) or 1 (inlier). - Once again, plot the decision boundary, but instead of drawing the training set, draw the test dataset and color code the inliers with blue and the outliers with red. You could do so by merging the test dataset with the predictions produced in step 12 and using one

plt.scatter()to plot the data observations where the prediction label is-1and another where the label is1. To merge the data, you could use the pandasconcat()function like this:pd.concat([X_test, pd.Series(test_predictions)], axis=1), wheretest_predictionsare the predictions from step 12. If everything works as planned, all the inliers are inside the red region and the outliers are in the blue one. The resulting plot should look similar to this one.

- Export the model to the host machine using the package joblib (it comes with scikit-learn’s installation). For details on how to do this, see the Resources section.

Use the Python framework FastAPI to develop a web service that hosts and serves the model’s predictions through a REST API. This service will run inside a Docker container.

- In this milestone, we will learn how to deploy and serve a machine learning model in a web service. By doing so, we “remove” the model from its typical training setting and bring it into an ecosystem where users can interact with it. As more industries start to adopt machine learning models inside their products, it is vital to know ways to present them to the customer.

- We will learn how to build a web service using FastAPI, a library that, in a short time, has proven itself to be a tool that is capable of rapidly setting up web services for large production systems. While doing so, we will explore concepts such as “GET” and “POST” methods, cURL, and an interactive document that excels at testing the service.

- As mentioned in Milestone 1, running services in Docker is becoming a common practice in the industry, and one of the reasons is the portability of Docker images. The service we will create here runs entirely inside a Docker image. Everything about it, including the model and dependencies, exists in the image and not on our computers. This “containing” nature allows anyone who has access to the image to execute the service without worrying about the details. As a bonus task, I will invite you to upload your image to Docker Hub.

- In Milestone 6, we will return to the service and add the metrics collection to it. In Milestone 7, we will integrate it with the monitoring stack.

- Within the same “liveProject” directory from Milestone 1, create a new directory and name it “service.” Go inside it and create a new Python file named

main.py. This file is where we will write the service. - Create a new requirements.txt and define the essential needed libraries (fastapi and uvicorn) plus those you find useful.

- Write the web service in

main.py. The web service needs two endpoints: one to handle the predictions and another for providing the model’s hyperparameters.- Before getting to the actual service, we first need to load the model we exported in Milestone 3.

- For the first endpoint, create a

POSTmethod with address/predictionthat accepts as input an object with a field namedfeature_vectorof typeList[float]. This field takes the vector we will input to the model to predict. The input object needs a second, but optional, field namedscoreof typebool. - The endpoint handler function needs to return an object with the field

is_inlier, which takes as a value the model’s prediction obtained after callingmodel.predict(), where the argument has to be the feature vector from the request object. Additionally, if the optional valuescoreistrue, add to the response object another field namedanomaly_scorewhose value is the predicted anomaly score. To get the anomaly score, predict using the isolation forest model’sscore_samples()method and use as an argument the input feature vector. Bothpredict()andscore_samples()return a list with the predictions, but because we are predicting with only one feature vector at a time, and thus producing one prediction, you can index the first element of the response array to index the prediction. To build the object to be returned by the handler function, you can create an empty dictionary (let’s call itresponse) at the beginning of the function and then add the fields as you handle the request. Then, at the end of the function, returnresponse. For a partial solution of the handler function, see the Hints section. - For the second endpoint, which is responsible for returning the model’s hyperparameters, create a

GETmethod under the address/model_information. Its handler function should return the object that was returned by the model’sget_params()method. This endpoint intends to provide a way to access the model’s information. Because we only have one model, having such an endpoint is not that critical; however, imagine having a service hosting several models and not knowing the particularities of each one of them. In such a scenario, it would make sense to provide a way to describe each model easily.

- Create a new Dockerfile that uses as a base the same Python image from Milestone 1.

- In the Dockerfile, use Docker’s

COPYinstruction to copy the Python script, the requirements.txt file, and the exported model to the Docker image. - After

COPY, useRUNto install the dependencies defined inrequirements.txt. - Lastly, use

CMDto run the command that starts the service. As before, I recommend using the--hostand--portoptions with values0.0.0.0and8000, respectively, to specify the desired host address and port.

- In the Dockerfile, use Docker’s

- After defining the Dockerfile, return to the terminal and build the image using the name

{your_name}/lp-service. Then, as we did before, run the Docker image using the publish or expose (-p) option to map the port you specified in theCMDinstruction to your computer. Doing so will start the Docker container with the web service running inside of it. - To test the service, go to the browser and access the address printed by the script followed by

/docs: for example,http://0.0.0.0:8000/docs. This link accesses the web service’s interactive API documentation. Here you can do things such as review the endpoints, look at their input schema, and even test the endpoints with a single click. In this step, we use the testing mechanism to test the web service.- For both endpoints, use the “try it out” option to test them right from the web browser. In the case of the

/predictionendpoint, try it twice: one time withscoreset tofalseand a second time withscoreset totrue. Iffalse, the response should be an object with a key score. Otherwise, ifscoreis true, the response should have a second key anomaly_score. For the/model_informationendpoint, the output should be an object where the keys are certain attributes of the model. - After executing each test, you will see a

cURLcommand already prepared with the address and input. Copy the commands and execute them from the terminal. The output you see there must be the same as the one from the interactive API documentation.

- For both endpoints, use the “try it out” option to test them right from the web browser. In the case of the

Use Docker Compose to run Prometheus and Grafana.

- In this milestone, we will learn how to set up a monitoring stack using Prometheus, Grafana, Caddy, and Docker Compose. In the previous milestones, we worked with containers that work on their own. While this works for small and simple projects, in real-world projects you will encounter many cases where you need to define and orchestrate multicontainer applications. To achieve this, one of the most accessible tools is Docker Compose.

- Generally speaking, metrics are an essential part of a production system. Platforms nowadays are far from simple. They consist of tens, if not hundreds, of moving parts: processes, inputs, outputs, and more. As a result, it is practically impossible to monitor them manually. For that, we have monitoring systems. With these tools, we can generate metrics that we could later use to assess the system. Moreover, these tools often support alerts, which (as the name indicates) are messages that are triggered when some specified condition is met. For a data-related project such as ours, monitoring is crucial. In this setting, we could monitor things like the status of the data sources or the predictions of a machine learning model; or, in the case of a real-time event system, we could measure the difference between the event time and the time it was processed (in other words, the lag). Figure 1 shows an example of a machine learning system presented in the previously cited paper, “Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems” by Sculley et al. There, you find the monitoring portion of the system sitting alongside the rest of the ML platform.

- In this milestone, we will add access control to Prometheus, thanks to Caddy. This feature is closely related to the concept of data governance, which is mentioned in the project’s introduction.

- In Milestone 7, we will return to the Docker Compose file to add our machine learning service and test the metrics we will gather in Milestone 6.

Before presenting the workflow, I’d like to take a few minutes to give a brief overview of the monitoring stack, its components, and how we will build it.

In this milestone, we will set up and run the monitoring stack that is responsible for tracking and visualizing the metrics we will gather in Milestone 6. The stack consists of three components: Prometheus, Grafana, and Caddy.

- Prometheus is a monitoring system and the platform on which we will write our metrics.

- Grafana is an analytics and dashboard solution that provides numerous charts to display metrics that are gathered in the data sources it supports. For our project, Prometheus is the data source.

- Caddy is a reverse proxy service that’s not directly linked to monitoring. However, we will use it as a basic authentication provider to control access to Prometheus’s web interface.

We will execute each of these platforms inside Docker containers. Moreover, because we must share data among the containers, we need a way to manage their interactivity. We do this with Docker Compose. Using Docker Compose involves working with a YAML file (known as docker-compose.yml) in which you configure the services. In the YAML file, you configure things like the name of the image you wish to execute, the ports to expose between the services, and the volumes each container needs. We will see more of this as we go through the exercise.

In past milestones, we created our Docker images. For this one, we leverage the portability feature of Docker and use images others have made. For reproducibility purposes, and to make sure we all have the same images, I recommend using the images shown in the following table.

| Platform | Docker Image |

|---|---|

| Prometheus | prom/prometheus:v2.20.0 |

| Grafana | grafana/grafana:7.1.1 |

| Caddy | stefanprodan/caddy |

- Within the same

liveproject/directory we’ve been using, create a new directory and name itmonitoring. Inside themonitoringdirectory , create a Docker Compose file nameddocker-compose.yml. - In the YAML file, specify the version of the Compose file format using the top-level key

version. Use the value3. For a quick introduction to Docker Compose and its terms, I highly suggest checking out the resources recommended at the end of this milestone. - After

version, create avolumestop-level key. Under this key, we will define and create the containers’ named volumes. In Docker terminology, a “volume” is storage used to persist data outside of the container. That way, the data won’t get destroyed even if the container is.- Under this tag, define two named volumes called

prometheus_dataandgrafana_data.

- Under this tag, define two named volumes called

- Let’s take a small break from the Compose file. In the same directory (

monitoring), create a new directory and name itprometheus, and inside it, create a file namedprometheus.yml. This file defines the target we wish to scrape (which is our ML service). Note that the file is another YAML, so it follows the same structure asdocker-compose.yml.- As a good practice, create a

globalkey. Under it, add the keyscrape_intervalwith the value set to15sto scrape each source every 15 seconds. - Then, create a second key,

scrape_configs, to configure the specific targets from which we want to scrape metrics. In our case, that’s the anomaly detector service. This tag requires several others:job_name,scrape_interval, andstatic_configs, with the latter needing a targets key whose value is a list of the addresses we want to scrape. Forjob_name, use the valueservice; forscrape_interval, feel free to choose any value (for example,10s); and fortargets, choose a list with one value,'service:{service_port}'(for example,['service:8000']).

- As a good practice, create a

- Back at the Compose file, we will now define the Prometheus service. To do so, create a

servicestop-level key. Under this key, create another one namedprometheus. Here, we require six keys to configure our Prometheus service; we will dedicate one section per key.- The first one is

image; use as the value the Prometheus image mentioned in the introduction. - Next is

container_name, which we should set toprometheus. - The third one is

volumes, and we need to define the volumes we want to use with Prometheus. One of the volumes we need to mount is a host volume where the source (the location on the host’s file system) is theprometheusdirectory we created in step 4 and the target is/etc/prometheus. The second volume is the named volume we created earlier; its target should be/prometheus. - The next key is

command, used to override the default commands. On this occasion, we will use it to set several options at the time of executing Prometheus.- The first flag is

--config.file. It needs to be set to the location of theprometheus.ymlfile within the container. In other words, it is not theprometheus.ymlfile we have on the host machine. For a hint, take another look at the host volume. - A second flag we need is

--storage.tsdb.pathto set where Prometheus writes its database. Set its value to the target of theprometheus_datanamed volume. - The last flag we will use is

--storage.tsdb.retention.timeto explicitly define when we want to delete the old data. It defaults to15d, meaning that data is stored for 15 days. Select a retention period that suits your needs: for instance,48h.

- The first flag is

- Next comes the

restartkey, used to set the restart policy. For our project, let’s useunless-stoppedto restart the container if it stops but not if it was manually stopped. - Last, use the key

exposeto expose a port and make Prometheus accessible to the other services. Note that this does not expose the container to the host machine. Use the port9090. - Before moving on to the next service, let’s test what we currently have to make sure we are on the right track. In the terminal (while at the monitoring/ directory), execute docker-compose up -d to start the container. Then, run docker ps to check the status. You should see something like this:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES 6f9dddb123ca prom/prometheus:v2.20.0 "/bin/prometheus --c…" 8 minutes ago Up 6 minutes 9090/tcp prometheus - The first one is

- Again, let’s step back from the Compose file. In the monitoring/ directory, create the (nested) directory grafana/provisioning/datasources and inside it a new file named datasources.yml. In this configuration file, you will add the data sources you want to use in Grafana.

- Go to the

datasources.ymlfile. In the first line, add the keyapiVersionand set its value to1. - Under it, add a

datasourceskey, whose value is a list of data sources we wish to add. We’ll add one (the Prometheus data source). - To define the data source, first add the

nameand use the valuePrometheus. (Because this is the first item in the list, you need to add a hyphen before the key.) Then add atypekey and set it toprometheus. Following this, create and setaccesstoproxy,orgIdto1, and theurltohttp://prometheus:9090. (Make sure the address matches Prometheus’s container name and the port is the exposed one.) Lastly, usebasicAuthand set it tofalseandisDefaultandeditabletotrue.

- Go to the

- Back in the Compose file, we will now define the Grafana service in a similar way to how we defined the Prometheus one. Once again, we need the same keys:

image;container_name;volumes;restart;expose; and one we didn’t see before,environment. (Note we do not needcommand.)- Set the values of the keys

image,container_name, andrestart. - For

expose, use 13000`. - As for

volumes, map the named volumegrafana_datato/var/lib/grafanaand create a host volume that maps the provisioning directory (not datasources) to/etc/grafana/provisioning. - In the

environmentkey, set three environmental variables. The first of these,GF_SECURITY_ADMIN_USER, specifies the default user. Set its value to the variableADMIN_USER(we will assign its value once we run Docker Compose): for example,GF_SECURITY_ADMIN_USER=${ADMIN_USER}. Additionally, you could add a default value in caseADMIN_USERis never set. (See the Compose file reference and guidelines.) The second env variable isGF_SECURITY_ADMIN_PASSWORD, and its value is the variableADMIN_PASSWORD. Then we haveGF_USERS_ALLOW_SIGN_UP, which allows new users to create accounts. We do not want this, so set its value tofalse. - To test Grafana, add a

portskey to the service definition to map the port3000to3000. Then, rundocker-compose up -dto run the containers and accesshttp://localhost:3000to see Grafana’s logging screen. That’s all for now. Again, please remove theportskey from the service.

- Set the values of the keys

- Now comes the last service: Caddy. Again, we will add a configuration file first and then define the file in Compose. In the monitoring directory, create a new directory named caddy, and inside it, create a file Caddyfile (without extension). At this point we will provide the content of the Caddyfile.

- Copy and paste the following in the Caddyfile:

` :9090 { basicauth / {$ADMIN_USER} {$ADMIN_PASSWORD} proxy / prometheus:9090 { transparent } errors stderr tls off } :3000 { proxy / grafana:3000 { transparent websocket } errors stderr tls off } `- The most important thing we are doing here is setting an authentication mechanism for Prometheus. So when a user accesses the Prometheus web interface, it will ask for

ADMIN_USERandADMIN_PASSWORD.

- Back in the Compose file, add the Caddy service.

- Define the

image,container_name, andrestartvariables. - Include a

volumekey with a host volume mapping thecaddydirectory to/etc/caddy. - Add an environment key with two environmental variables,

ADMIN_USERandADMIN_PASSWORD, whose values are the same as those you used for Grafana’sGF_SECURITY_ADMIN_USERandGF_SECURITY_ADMIN_PASSWORD. - Last, use the key

portsto forward the ports3000and9090to3000and9090, respectively (similar to how we did it with the Dockerfile). This mapping will ensure the local machine has access to Grafana and Prometheus.

- Define the

- Now let’s test the system. In the terminal (while at the monitoring directory), execute

ADMIN_USER=admin ADMIN_PASSWORD=admin docker-compose up -dto start the containers. That’s all we need. To make sure they are running, run docker ps to check the status. - In the browser, go to

http://127.0.0.1:9090/graphto access the Prometheus console. It will first ask you to enter the user’s credentials; use “admin” and “admin.” For now, there’s not much to see because we are not collecting any metrics yet. To double-check everything, go to status -> configuration, and you should see thescrape_configsobject you defined earlier. Next, go tohttp://127.0.0.1:3000/?orgId=1to access Grafana. Again, it will ask for your credentials. While in it, go to configuration -> data sources, and you should find the Prometheus data source. Then create a new dashboard and name it “Service.” We’ll return to it later.

In this milestone, we will collect metrics from the web service using the library prometheus_client and create a dashboard to visualize them. We will then add the service to the Docker Container file to run it alongside the monitoring stack.

- In this milestone, we learn how to create and export Prometheus metrics using Python and the library prometheus_client. In the process, we learn about the counter and histogram metrics, which are two of the most used. However, these aren’t the only ones. Another core metric Prometheus provides is the gauge, which represents a numerical value that can increase and decrease.

- Picking up the topic about the importance of metrics discussed in Milestone 5, we need to point out the obvious observation that working with metrics involves more than just collecting them; we need a way to present and interpret them. One of these options is a dashboard, like the one we just did. Being in this course might imply that you have a data-related background. If so, you have an idea of how the principles of building a data visualization should apply in this setting: for example, axis labels, correct units, simplicity, and clarity. These principles also apply to dashboards, and I’m willing to say that “clarity” is at the forefront. That’s because you will typically see these dashboards on large screens located in some corner of the office, and so you should be able to understand them in a single glance.

- In the next and final milestone, we will thoroughly test the service and metrics by writing a script that reads the test dataset and requests predictions from the service.

Prometheus Python client, or just prometheus_client, is a Python library for gathering metrics and exposing them to Prometheus. The library supports four types of metrics: counter, gauge, summary, and histogram . A counter is a cumulative metric whose value can only go up, and a gauge is a numerical value that can go up and down. The other two, summary and histogram, sample observations into buckets, with the difference being that a summary calculates the quantiles on the client side over a sliding time window of values, and a histogram calculates the quantiles on the server side.

- In the requirements.txt file we used in Milestone 4, add the package

prometheus_client(Prometheus Python Client). - In the service script (

main.py), create a new ASGI app using the functionmake_aspi_app()fromprometheus_client. Then, use themount()method from the ASGI object to mount the ASGI app at the/metricsendpoint to expose the collected metrics on that endpoint. For a hint, see this GitHub thread or the Hint sections of this milestone. - After setting up the metrics endpoint, the next step is creating the Prometheus metrics.

- First, create two Prometheus counter metrics that increase by 1 whenever the endpoints are called (add one in each endpoint handler function). For an example of how to create a counter metric, see “Counter” on the Prometheus website.

- In the

/predictionendpoint, add a Prometheus histogram to track the model’s prediction response. Name the histogrampredictions_output(you can set the name in the first argument of theHistogram()function). For an example of how to create a histogram metric, see “Histogram” on the Prometheus website. - In the same

/predictionendpoint, add a second histogram to track the score sample predictions. Name itpredictions_scores. - Last, also in the

/predictionendpoint, add a histogram to track the function’s latency. Hint: Calculate the current time at the beginning of the function and subtract it from the current time in the end; the difference is the latency.

- Update the machine learning Docker image by building it.

- In the Docker Compose file, add the web service to the

servicestop-level key. The name of the image has to be the one defined in Milestone 4: for example,{your_name}/lp-serviceand the container name,service. Then, expose port8000and map the port8000from the container to8000from the host machine. This port number has to be the same one you added in Milestone 5, step 4.2. - Run the complete platform using Docker Compose. Doing so will start the machine learning service and others.

- To check if the metrics are working correctly, go to the browser and access

http://localhost:8000/metrics/. Here, you will see the metrics you defined plus others that were automatically added byprometheus_client. - Now, visit the Prometheus web client (

http://localhost:9090/graph). In the search bar, type the name of any of the metrics followed by pressing Enter. There, you will see the default value of the metric. - To start collecting metrics, go to the service’s page interactive documentation page (

http://localhost:8000/docs) and make several requests. Then, return to Prometheus and search for the metrics. This time, you should see values other than the default ones. - For the last step, we’ll create the dashboard in Grafana.

- Access Grafana from its address,

http://127.0.0.1:3000. - Create a new dashboard. In the dashboard, you will see an empty area with a button that says, “add a new panel.” Click it.

- In the PromQL query space below, search for the “predictions counter” metric (step 3.1). After that, click the “Query” button to add a second PromQL query with the “model information counter” metric in the same panel. Because both metrics are counters, make sure you select the one with “_total” suffixed to the name.

- Grafana will automatically ask you to fix the metric by adding the

rate()function. Click the message to add it. If Grafana does not give you the option, add it manually. As stated in the official documentation, the rate function “calculates the per-second average rate of increase of the time series in the range vector.” For more information, please consult the function’s documentation, “rate().” - Back on the main dashboard screen, add a new panel. Here, we will display the histograms defined in steps 3b and 3c. A histogram metric is like a statistical histogram, where you have buckets with values falling into them, with the difference being that this one is constantly calculating its quantiles. So, we don’t have the actual collected values. Instead, we have each bucket’s count, the total sum of all the collected values, and the total count of values. For this panel’s first query, we want to have the increasing, average model’s output value within a sliding window of 30 seconds. Let’s do it together. To create it, we will use the

predictions_scores_sumandpredictions_scores_countmetrics that are automatically added by Prometheus’s histogram. In the query area, we will write the following:sum(increase(predictions_scores_sum[30s])). Theincrease()function computes how much the vectorpredictions_scores_sumincreased in the last 30 seconds. Then, with thesum()function, we sum up all the values of the vector. But that’s not the end. Because we want the average, we need to divide this number by the count, which is obtained with the expressionsum(increase(predictions_scores_count[30s])). So, the final formula should look like this:sum(increase(predictions_output_sum[30s])) / sum(increase(predictions_output_count[30s])). Now, repeat the same steps but with thepredictions_scoresmetric. - Lastly, create a new panel and add to it the latency metric using the same approach from the previous step. Because this metric measures time, go to the panel settings and change the left y-axis unit to the time unit you used.

- Access Grafana from its address,

- Return to the dashboard and save it.

In this last milestone, we will write a script that loads the dataset and uses its data to request predictions while generating metrics. The goal here is to test the system while creating enough metrics to populate our dashboards.

- In this milestone, we will write a script that requests predictions from the web service. During the process, we’ll test most of the platforms and their functionality. For instance, we’ll test the endpoints and the required inputs and produced outputs while also ensuring that the anomaly detector service is up and running at the correct address. Besides this, by generating metrics and seeing them in the dashboard, we will confirm that the whole monitoring stack, and the dashboard, are working in the way we intended.

- In our working directory, create a new file and name it tester.py.

- In tester.py, load the testing dataset.

- Write a function that loops over the dataset. At each iteration, do the following:

- Request a prediction using the feature vector from the current iteration.

- There should be a 25% chance of setting the “score” optional setting to

true(see Milestone 4, step 3).

- Request a prediction using the feature vector from the current iteration.

- At the end of the function, call the /model_information endpoint.

- Run the script. Note that we are not using Docker this time; instead, run it locally. If the rest of the platform is not up, run it using Docker Compose (see Milestone 5, step 13).

- Finally, go to the Grafana dashboard to see the metrics we just generated.