Have you heard the saying “releases should be boring”? This is the unofficial motto of Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD). GitHub Actions, announced at the 2018 GitHub Universe Conference, aims to bring boring releases to all users in the GitHub Ecosystem. Today we’ll start by covering why GitHub Actions is an important development in social coding and then we'll look at the core concepts that Actions uses to create an automation system. Lastly, we’ll build and deploy a serverless API using AWS, the Serverless Framework, and GitHub Actions. Note that the following prerequisites are required to complete the API tutorial:

- An AWS Account (set up Free Tier Access Here) AWS Free Tier

- An AWS IAM User with Programmatic Access (see here for a good starter IAM Policy and note that you should always follow the Principle of Least Privilege when setting up an IAM User)

- The

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_IDandAWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEYof the user above. - GitHub Account enrolled in the GitHub Actions Beta

- Clone or fork of the repo https://github.com/twobulls/github_actions

Social coding is a software development practice centered around the belief that community and collaboration build the best software. There are numerous examples of social coding, including GitHub, open source software in general, and package managers like npm. Social coding allows builders to share effort and to work collaboratively on software. GitHub Actions is an important step forward in social coding because it introduces a feasible way to share automation.

Automation and CI/CD tend to be boilerplate-heavy. This leads to repetitive code and time wasted on work that doesn’t actually differentiate your application. Actions enables streamlined access to automation tools and the ability to easily share these tools. Actions is Docker-based which affords portability and ease-of-sharing. GitHub takes advantage of this by allowing builders to incorporate Actions from any public GitHub repository or any Docker image on DockerHub. Of course, if a particular Action does not exist a builder can create custom Actions and optionally share them in a public repository. The combination of integrated automation tools and ease-of-sharing is what makes Actions an excellent strategic opportunity for GitHub and a boon for builders in GitHub ecosystem.

In any large-scale social coding platform it’s important to be aware of potential issues caused by version changes and vulnerabilities introduced accidentally or maliciously. Actions is no exception. GitHub has addressed some of the issues including access control and version-pinning, but there are some other issues which we will explore later. Next, we’ll dive into the core concepts of GitHub Actions.

Workflows can be created in code or using the visual editor. The following examples will use the configuration language that Actions provides.

Actions are “code that run in Docker containers”. Although Actions share their name with the wider service, they are the individual units of work to be performed. Each Action has a unique name and one required attribute, namely uses. An Action is defined using the action block:

action "Unique Name" {

uses = "./actions/helloworld"

}

The uses attribute can reference an Action in the same repo, a public Action in a GitHub repository, or a public Docker container hosted on Dockerhub. Don't worry too much if you are unfamiliar with Docker. We will do a brief overview of the commands used later on. This Action references the following Docker container:

# actions/helloworld/Dockerfile

FROM golang:1.11.4-stretch

LABEL "com.github.actions.name"="Echo Hello World"

LABEL "com.github.actions.description"="Say Hello to the World!"

CMD echo "Hello World!"You can provide other optional attributes depending on your needs. A few common attributes including needs, secrets, and args will be discussed later. For a full list of attributes see the official documentation official documentation.

Events are “happenings” within your GitHub repository including pull_request_review, push, and issues. Events trigger different workflows and have different environment variables depending on the type of event. This is important because the commit that the Action runs against depends on the event type triggering the Action.

For example, the release event resolves the GITHUB_SHA (the commit hash) by the tag that triggered the release. So, an Action triggered by the release event uses the latest commit SHA of the branch.

But, the push event’s GITHUB_SHA is “Event specific unless deleting a branch (when it's the default branch)”. This means that it grabs the commit SHA directly from the triggering event.

You can read more about the available events and the SHA resolutions in the official documentation.

Workflows are composed of Actions and are triggered by Events. Put another way, Workflows combine Events and Actions. Workflows are defined using the workflow block. Each workflow block needs a unique name and has two required attributes: on and resolves. In the on attribute you define the Event type that triggers the Workflow. In the resolves attribute you describe the Actions to be “resolved” by the workflow. The workflow block definition reads like a sentence in English: “The workflow named Deploy Staging, on the release event, resolves build, test and deploy.”

workflow "Deploy Staging" {

on = "release"

resolves = ["build", "test", "deploy"]

}

The resolves attribute deserves a little more attention, which we will cover next.

Dependency between Actions can be expressed using the needs attribute. In the example below, “Deploy” is dependent on the successful completion of “Build”, “Test”, and “Lint”. You’ll notice that we include only the “Deploy” action in the resolves attribute of the Workflow block:

workflow "Deploy to Staging" {

on = "release"

resolves = "Deploy"

}

action "Build" {

uses = "docker://image1"

}

action "Test" {

uses = "docker://image2"

}

action "Lint" {

uses = "docker://image3"

}

action "Deploy" {

needs = ["Build", "Test", "Lint"]

uses = "docker://image4"

}

This is because the “Deploy” Action is dependent on the completion of the “Build”, “Test”, and “Lint” actions. We can express complex dependencies using this style.

My initial assumption was that, in the workflow above, “Build”, “Test”, and “Lint” would run in parallel considering they are independent Actions. In practice, this hasn’t been the case. I tried the following workflow format, which I also expected would run in parallel:

workflow "Deploy to Staging" {

on = "release"

resolves = ["Build", "Test"]

}

action "Build" {

uses = "docker://image1"

}

action "Test" {

uses = "docker://image2"

}

Once again, this was not the case and the above did not run in parallel. According to the documentation “[w]hen more than one action is listed [in the resolves attribute] the actions are executed in parallel.” This may just be a limitation of the Public Beta and I imagine Actions will allow parallelism in the future.

The Workspace is the directory in which your Action will do its work. The workspace directory contains a copy of the repository set to the GITHUB_SHA from the Event that triggered the workflow. An Action can modify this directory, access the contents, create binaries, etc. We’ll use the Workspace to store the compiled Go binary generated by our Action.

Actions allow access to secrets through the secrets attribute. You have to explicitly list which secrets an Action has permission to access. In the following example the “Deploy Hello World” Action is given permission to access the AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and the AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY.

action "Deploy Hello World" {

needs = ["Build Hello World", "Lint Hello World"]

uses = "serverless/github-action@master"

secrets = ["AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID", "AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY"]

args = "deploy"

}

Secrets are added through the repository settings panel and are exposed as environment variables to the Action.

Note: GitHub Actions recommends that during the Public Beta you do not store any production secrets at this time. For more information read the official documentation.

Next, we’ll build a serverless API. The Workflow will build, lint, and deploy on each push to the master branch in our repository.

Grab the AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY from the IAM user you created. In the “Settings” page in your repository click on “Secrets” and add the AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY. Note: during the public beta do not store any production secrets in the repository.

Serverless Framework handles infrastructure and provisioning of Serverless Applications. The infrastructure is defined in the serverless.yml file, so that’s where we’ll look first. Serverless uses a minimal configuration language to link events with the desired computation. Here we are creating an http api GET /hello and handling the API event with the Go binary in bin/hello .

# serverless.yml

...

functions:

hello:

handler: bin/hello

events:

- http:

path: hello

method: getNext, we’ll view the source code for the bin/hello binary. This code uses Serverless Framework’s default Go template with a slight modification to the message body:

// hello/main.go

...

type Response events.APIGatewayProxyResponse

func Handler(ctx context.Context) (Response, error) {

var buf bytes.Buffer

body, err := json.Marshal(map[string]interface{}{

"message": "Hello From Two Bulls!",

})

if err != nil {

return Response{StatusCode: 404}, err

}

json.HTMLEscape(&buf, body)

resp := Response{

StatusCode: 200,

IsBase64Encoded: false,

Body: buf.String(),

Headers: map[string]string{

"Content-Type": "application/json",

},

}

return resp, nil

}

...This function returns an APIGatewayProxyResponse which defines the status code, headers, and response body.

The Makefile defines the build steps that the Action will run. Two things worth noting: This is using Go 1.11 module system and we’re setting the GOOS environment variable to linux since we’ll be running this function in AWS Lambda.

build:

export GO111MODULE=on

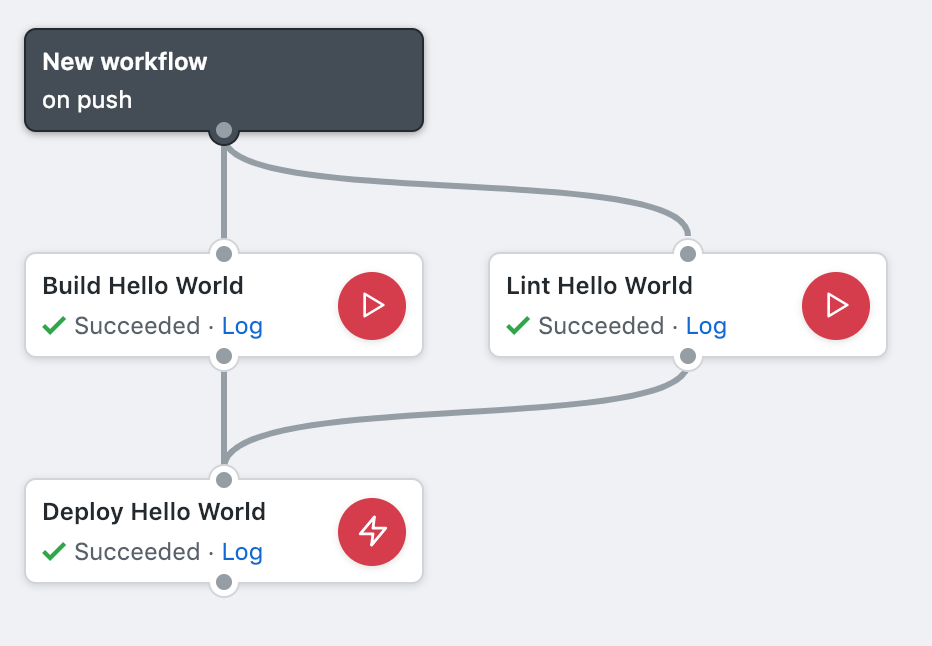

env GOOS=linux go build -ldflags="-s -w" -o bin/hello hello/main.goNext we’ll take a look at the GitHub Actions Workflow and Action definitions. Here we’ve defined a Workflow that is triggered on every push event and resolves the “Deploy Hello World” Action. The “Deploy Hello World” Action uses an external Action, maintained by the Serverless GitHub organization. To refer to this external Action we use the organization name, the repo name, and the commit-ish that we’d like pin the version to. Additonally, we explicitly grant this Action access to the AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY secrets that we created earlier. The args attribute is the argument that we pass to the Action -- since this Action is wrapping the Serverless Framework we want to pass the deploy argument, but any Serverless command can be run here. The “Deploy Hello World” Action needs the “Build Hello World” and “Lint Hello World” Actions, but these are defined in our repository and thus can be referenced using the relative path syntax. These will complete before the “Deploy Hello World Action”.

workflow "New workflow" {

on = "push"

resolves = "Deploy Hello World"

}

action "Build Hello World" {

uses = "./actions/build"

}

action "Lint Hello World" {

uses = "./actions/lint"

}

action "Deploy Hello World" {

needs = ["Build Hello World", "Lint Hello World"]

uses = "serverless/github-action@master"

secrets = ["AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID", "AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY"]

args = "deploy"

}

The Actions defined in our repository reference Docker files. We’ll do a quick overview of the Docker syntax used here and what it means.

FROM defines the base image that we’ll use for our container. We’re using golang:1.11.4-stretch which comes with the dependencies necessary for building Go. Additionally, it comes with the go tool installed.

LABEL provides metadata about our container. We can include a name, description, and other metadata, including how the Action should appear in the visual editor.

CMD is the command that we’d like to run when the Docker container starts. This is where we’ll spend most of our time writing the commands we’d like our container to perform.

With that quick introduction we can look at the Dockerfiles in our repository. The “Build Hello World” container runs make . Make runs the steps in the Makefile discussed above. The “Lint Hello World” container runs go vet against the Go source code in our repository.

# actions/build/Dockerfile

FROM golang:1.11.4-stretch

LABEL "com.github.actions.name"="Build Hello World"

LABEL "com.github.actions.description"="Run make to build the Golang binary."

CMD make# action/lint/Dockerfile

FROM golang:1.11.4-stretch

LABEL "com.github.actions.name"="Lint Hello World"

LABEL "com.github.actions.description"="Lint the hello world application using go vet."

CMD cd hello && go vetWith everything set up, we’re ready to deploy the API. You can make a change to README.md, commit, and push. Open the Actions panel in the repository and you can watch as the actions queue and begin work. You can open the logs and watch the log output as well. When an Action completes successfully you’ll see a green checkmark on each of the Actions.

Next, view the logs of the “Deploy Hello World” Action.

Serverless: Stack update finished...

Service Information

service: go-github-actions

stage: dev

region: us-east-1

stack: go-github-actions-dev

api keys:

None

endpoints:

GET - https://xxrefpqkp2.execute-api.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/dev/hello

functions:

hello: go-github-actions-dev-hello

layers:

None

Serverless: Removing old service artifacts from S3...

### SUCCEEDED Deploy Hello World 23:54:39Z (1m23.488s)

The URL for your API is listed in endpoints. Open the url and you’ll see the following:

{"message":"Hello From Two Bulls!"}Voila! A serverless API deployed by GitHub Actions.

There are a few limitations to be aware of when using GitHub Actions. First, it is still in a limited public beta, so changes to APIs, features, and limits can be expected to change.

- Run for 58 minutes (queueing AND execution time)

- Each workflow can run up to 100 actions

- Two workflows concurrently per repository

You can read the full list in the official documentation.

As hinted at earlier, Actions mitigates some potential security issues by allowing version-pinning and explicit access control to secrets. When using external actions you need to trust the author. When integrating an external Action you should ask a few questions:

- Is there a way to know that an Action is compromised from a security perspective?

- How much access does an external action need?

- What is the external action doing with your secrets if you grant access?

These problems are not necessarily unique to GitHub Actions, but instead, are a wider problem in the social coding era. A few potential mitigations for this problem would be alerts about compromised external Actions and a freeze on Workflows using compromised Actions. But until those features are implemented, be sure to trust the Actions that you're using.

Today you learned about GitHub Actions and deployed a serverless API. GitHub Actions is extremely flexible and this just scratches the surface of what is possible. Because of the diversity of events available, Actions can integrate with GitHub Issues and with external communication tools like Slack. You can build automation for lots of common tasks. But most importantly, you can share that automation and use automation that others have already built.