Embedded devices with limited memory and storage resources are likely to leverage a tool such as BusyBox, which is marketed as the Swiss Army Knife of embedded Linux. BusyBox is a software suite of many useful Unix utilities, known as applets, that are packaged as a single executable file. You can find within BusyBox a fully fledged shell, a DHCP client/server, and small utilities such as cp, ls, grep, and others. You’re also likely to find many OT and IoT devices running BusyBox, including popular programmable logic controllers (PLCs), human-machine interfaces (HMIs), and remote terminal units (RTUs)—many of which now run on Linux.

As part of our commitment to improve open-source software security, Claroty’s Team82 and JFrog have collaborated to perform a deep vulnerability research on BusyBox. Using static and dynamic techniques, Claroty’s Team82 and JFrog have discovered 14 vulnerabilities affecting the latest version of BusyBox. All vulnerabilities were privately disclosed and fixed by BusyBox in version 1.34.0, which was released Aug. 19.

BusyBox consists of dozens of UNIX-like programs which are also known as applets. By calling make config, users can customize applets and compile only applets relevant to them into one unified and easy to use binary.

These programs can be run simply by adding their name as an argument to the BusyBox executable:

/bin/busybox ls

More commonly, the desired command names are linked (using hard or symbolic links) to the BusyBox executable; BusyBox reads argv[0] to find the name by which it is called, and runs the appropriate command, for example just /bin/ls after /bin/ls is linked to /bin/busybox. This works because the first argument passed to a program is the name used for the program call, in this case the argument would be /bin/ls BusyBox would see that its name is ls and act like the ls program.

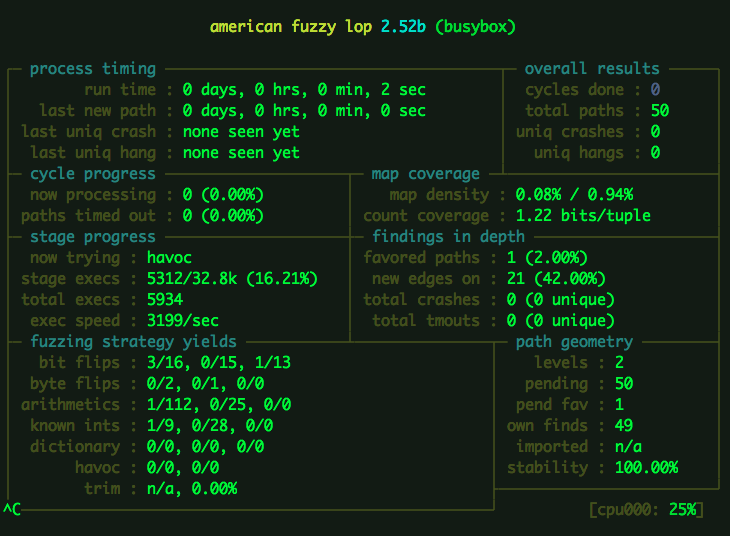

Fuzzing applets with AFL can be very useful for finding memory corruptions within busybox applets. Fuzzing is an automated testing method that directs varying input data to a program in order to monitor output. It is a way to test for overall reliability as well as identify potential security bugs.

The fuzzer we are using is AFL, a fuzzer that uses runtime guided techniques to create input for the tested program. From a high-level perspective AFL works as follows:

- Forks the fuzzed process

- Generates a new test case based on a predefined input

- Feeds the fuzzed process with the test case through STDIN

- Monitors the execution and registers which paths are reachable

Applets can receive input data from multiple sources, including:

- ARGV: for example reading

lsarguments -ls -lat - STDIN: for example

bc-echo 1+1 | bc - Files: for example reading file for processing -

lzma -d /path/to/file.lzma - Network (servers): for example

DHCP, DNS, HTTP, TELNET, and more. - Network (clients): for example

NSLOOKUP, HTTP Client

Depending what we are planning to fuzz, we would need to modify the source code in a specific way so it will fit our needs.

To start fuzzing busybox with AFL you'll need to compile it with AFL. First make sure you have AFL installed:

wget http://lcamtuf.coredump.cx/afl/releases/afl-latest.tgz

tar xzf afl-latest.tgz

cd afl*

make && sudo make install

echo "AFL is ready at: $(which afl-fuzz)"Next, we need to obtain the latest version of busybox and compile with AFL. Choose one of the available busybox versions listed here. In our research we worked with 1.33.1 stable because at the time it was the latest version available.

First let’s compile busybox without AFL:

wget https://git.busybox.net/busybox/snapshot/busybox-1_33_1.tar.bz2

tar -xvf busybox-1_33_1.tar.bz2

cd busybox*

# DO: run one of the configurators (e.g. "make oldconfig" or "make menuconfig" or "make defconfig"). We will use the default settings.

make # to make sure busybox is compiled successfully

echo 1+1 | ./busybox bc

echo 1+1 | ./busybox_unstripped bc

cp busybox busybox_orig

cp busybox_unstripped busybox_unstripped_origNow you should have a busybox and busybox_unstripped binaries. We would want to save a copy of them so we will have the original binaries in case we want to play with them later.

Next let’s compile a busybox with AFL. To do so, we would need to edit Makefile and change the compiler to afl-gcc or afl-clang. We will

To compile with afl-gcc, In Makefile:

- Under

# Make variables (CC, etc...)editccto:CC = afl-gcc

To compile with afl-clang, In Makefile:

- Under

# Make variables (CC, etc...)editccto:CC = afl-clang

- And edit LDFLAGS:

LDFLAGS="-Wl,--allow-multiple-definition" make -j12

Now save Makefile and re-run make install.

Directory structure:

- busybox (binary)

- fuzz (dir) <-- we will be in this directory

- input (dir)

- output (dir)

To verify that the new busybox binaries were compiled correctly with AFL, let’s run a simple AFL instance.

mkdir fuzz && cd fuzz

mkdir input

mkdir output

echo "1+1" > ./input/test.txt

afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busyboxAt this point it won’t do much because we are trying to send fuzzed inputs through STDIN and the code flow doesn’t reach any applet which is specified through ARGV.

But if we will run:

afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox bcWe will fuzz the bc applet as it takes input from STDIN.

As mentioned above, there are 4 main ways to deliver inputs to busybox, but the applet to be used is determined by ARGV in place 0 or 1 depending how we are using BusyBox. In the normal use case, we will call busybox as follows:

busybox APPLET ARGS

For example, busybox ls -lat.

So a simple example would be to fixate busybox to always call ls and take the arguments from STDIN.

By default AFL transfer input data through STDIN. Therefore we want in each fuzzing cycle to read from STDIN and generate a new ARGV array. Let’s patch busybox_main (libbb/appletlib.c) with the following code:

static char in_buf[100000];

static char* ret[1000];

char* ptr = in_buf;

int rc = 0;

// read from STDIN to in_buf

if (read(0, in_buf, 100000 - 4) < 0) {

while (*ptr) {

ret[rc] = ptr;

/* insert '\0' at the end of ret[rc] on first space-sym */

while (*ptr && !isspace(*ptr)) ptr++;

*ptr = '\0';

ptr++;

/* skip more space-syms */

while (*ptr && isspace(*ptr)) ptr++;

rc++;

}

}

ret[rc] = 0;

ret[rc+1] = 0;

argc = rc;

argv = ret;

applet_name = bb_basename(argv[0]);

// choose specific applet name

run_applet_and_exit("ls", argv);

// or take from argv[0] (random)

// run_applet_and_exit(applet_name, argv);By default AFL transfer input data through STDIN, so we don’t need to do much. For example, bc utility takes input from STDIN, so this should work out-of-the-box:

afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox bc

More examples for utilities that support STDIN input:

afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox gunzip -c -afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox unlzma -c -afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox bunzip2 -c -afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox tar -vtO -afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox tar -vxO -

Some applets take input from files. For example awk and grep (first create a.txt):

afl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox awk -f @@ ./a.txtafl-fuzz -i ./input/ -o output/ -- ../busybox grep -f @@ ./a.bin

Fuzzing network servers possess some problems when using AFL. AFL is built to be a file-based fuzzer and adding a network aspect to it is tricky. That’s why we decided to focus on the response-parsing functions of the network servers. For most server attacks the response is the data that attackers control.

HTTPD Is the easiest applet to fuzz out of all of the network applets. HTTPD includes the option to run it in inetd mode - meaning that it will parse one packet and exit.

To run AFL on the HTTPD server:

afl-fuzz -m none -i ./input -o ./output -- ./usr/sbin/httpd -f -i ./www

To fuzz HTTPD options that are disabled by default run the httpd server with a custom configuration file specifying what features to enable

In order to fuzz the DNS response packet handling we changed the dnsd_main (networking/dnsd.c) function to the following code:

int dnsd_main(int argc, char `argv) MAIN_EXTERNALLY_VISIBLE;

int dnsd_main(int argc UNUSED_PARAM, char `argv)

{

struct dns_entry *conf_data;

uint32_t conf_ttl = DEFAULT_TTL;

const char *fileconf = "/etc/dnsd.conf";

conf_data = parse_conf_file(fileconf);

uint8_t buf[MAX_PACK_LEN + 1] ALIGN4;

ssize_t r;

while (__AFL_LOOP(1000)) {

r = -1;

memset(buf, 0, MAX_PACK_LEN);

r = read(STDIN_FILENO, buf, MAX_PACK_LEN);

if (r < 12 || r > MAX_PACK_LEN) {

// bb_error_msg("packet size %d, ignored", r);

continue;

}

// if (OPT_verbose)

// bb_simple_info_msg("got UDP packet");

buf[r] = '\0'; /* paranoia */

r = process_packet(conf_data, conf_ttl, buf, r);

}

return 0;

}This code only does some essential initializations and then calls the process_packet with a buffer read from STDIN.

Similar to dnsd we reduced the nslookup_main (networking/nslookup.c) to the following:

int nslookup_main(int argc, char `argv) MAIN_EXTERNALLY_VISIBLE;

int nslookup_main(int argc UNUSED_PARAM, char `argv)

{

int res;

unsigned char reply[512];

int recvlen;

while (__AFL_LOOP(1000)) {

recvlen = read(STDIN_FILENO, reply, sizeof(reply));

res = parse_reply(reply, recvlen);

}

exit(0);

}- Run multiple AFL processes in parallel

- Compile with afl-fast (clang) and add

__AFL_LOOPsection - Use dictionaries with relevant keywords (arguments, applets)

- Stop all running services (for example:

cups, apparmor, fail2ban, postgresql, mariadb, rabbitmq-server, redis, firewalld) - Add to the machine more RAM and CPUs if possible

Address Sanitizers (ASAN) track memory actions such as malloc, free, memcpy to provide better detection of memory corruption errors. A program compiled with ASAN will exit with a signal when a memory corruption is detected, so AFL is able to detect that as a crash.

Fuzzing a binary compiled with ASAN helps find memory corruption bugs even in cases where the regular binary won’t crash(Some cases of a small heap read overflow for example).

Busybox provides the option to compile with ASAN using the menuconfig:

Go to Settings --> Enable runtime sanitizers (under Debugging Options)

Address Sanitizer are useful, but also make the program much slower so compiling with ASAN is a trade off between speed and better corruption detection.

We recommend to prepare a separate version compiled with ASAN for the triage process and not use it while fuzzing.

Since busybox can control some aspects of the operating system, it is recommended to run all fuzzing instances under a contained and restrictive environment. This can include running inside a container and/or a chroot jail with limited access to the real OS resources.