The contents of this readme is public domain where possible. And if licensing is required, it may be licensed under the MIT, NewBSD, ISC, Zlib, MIT0 or CC0 licenses.

Included are the URLs directly to the headers themselves. You can "Copy Link Location" then wget or curl it into where you need it.

Single-file-header only libraries are intended to make it easy to add funcitonality to a C project without extra build steps and most of the time come with zero dependencies.

The pattern is typically:

In one .c file in your project:

#define PACKAGE_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "package.h"

Note: if you are doing this from a header file, be sure to #undef PACKAGE_IMPLEMENTATION afterwards.

If you need the header file to use it in other .c files in your project, just include the package, directly.

#include "package.h"

Note that some header-only libraries are actually .c files. But that's ok, you can just #include the c file in your code.

| Name/Package/Page | Description | File/URL |

|---|---|---|

| stb | Easily write .bmp, .png, .tga, .jpeg files from C | stb_image_write.h |

| stb | Load .ttf files and get raster pixel data | stb_truetype.h |

| stb | Load .png, .pnm, .jpg, .bmp, .psd, .tga, .gif, .hdr, and .pic files | stb_image.h |

| olive.c | Tiny graphics library for working on pixel buffers | olive.c |

| frog_utf.h | Utilities for converting between characters, UTF-8, UCS, etc. | frog_utf |

Single-file headers I wrote:

| Name/Package/Page | Description | File/URL |

|---|---|---|

| rawdraw | Window / opengl context creation, input management on many platforms (like SDL but 1/1000th the size) good for Android, Linux, Windows, Web | rawdraw_sf.h |

| hufftreegen_sf | Create huffman trees of bitstreams, and the means to decode them | hufftreegen.h |

| cnrbtree | Arbitrary header-only (with macro magic) red-black tree | cnrbtree.h |

| cnhash | C Hash table/map implementation | cnrbtree.h |

| mini-rv32ima | Header-only RISC-V Emulator capable of booting nommu linux | mini-rv32ima.h |

| heatshrink-sfh | Very stripped down implementation of the heatshrink LVSS decompression algorithm | heatshrink_sf.h |

| rtgz-tinf-util | Custom deflate decompressor, and custom compressor for targeting tiny decode windows | tinf_sf.h |

| csgp4 | SGP4 Orbital Mechanics Header-Only file (portable to HLSL) for computing satellite positions at times | csgp4.h |

- dwillmore's bit math

- Stanford bit twiddling hacks

- cnlohr's assembly notes

- hexagon math grids and equations for how to work with hexagons

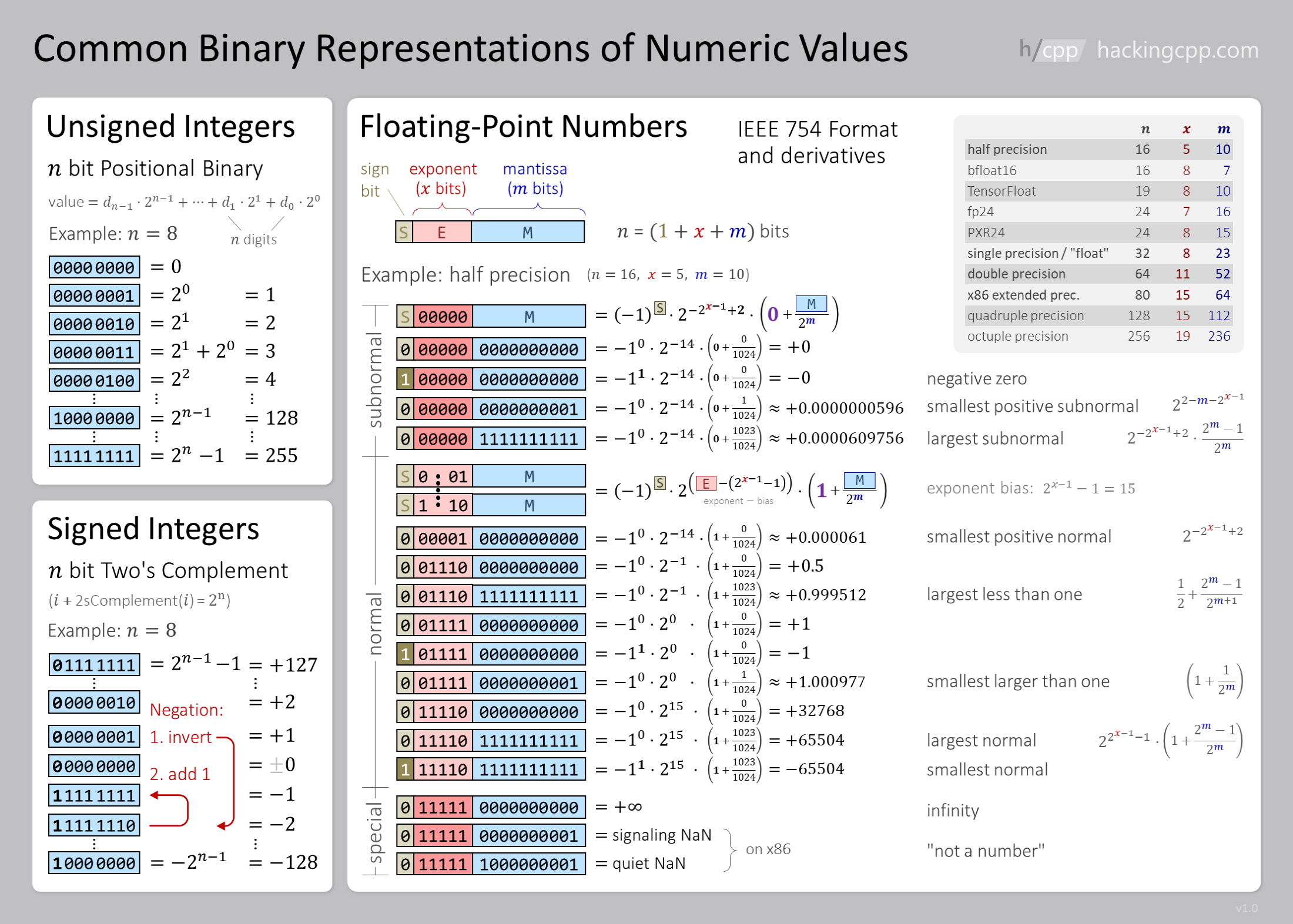

All modern comptuers store numbers in two's complement. Basically for unsigned numbers, you can binary count up.

For an 8-bit number (like a uint8_t):

0 = 00000000

1 = 00000001

2 = 00000010

3 = 00000011

...

254 = 11111110

255 = 11111111

So, when you overflow, you go from 255 back to 0.

For signed numbers, the MSB (most significant bit) indicates if the number is negative, so you get:

0 = 00000000

...

127 = 01111111

...

-128 = 10000000

...

-1 = 11111111

So, counting goes 0, 1, 2, 3 ... 127, -128, -127, -126, ... -2, -1, 0.

This means:

- There is one more negative number than positive numbers.

- 0 is just all 0's.

- If you typecast an unsigned number that is >128 to a signed number, it will become negative.

For sign-extension, compilers can automatically fill out a sign. For instance:

int8_t i = -127; // 0b10000001

int j = i; // 0b11111111111111111111111110000001

// j is still -126, even though the compiler had to fill out a lot more 1's in the beginning.

There are times when you will want to use other non-8-bit-values for numbers. You can also force sign extension in these situations.

int32_t k = 0b1011; // -5 in 4-bit, but k=13

k = (k << (32-4) >> (32-4));

// k is now -5.

Depending on the type size, you have different constraints. Here is a quick table for different values:

| bits | Signed Minimum | Signed Maximum | Unsigned Minimum | Unsigned Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | -8 | 7 | 0 | 15 |

| 8 | -128 | 127 | 0 | 256 |

| 16 | -32,768 | 32,767 | 0 | 65,535 |

| 24 | -8,388,608 | 8,388,608 | 0 | 16,777,216 |

| 32 | -2,147,483,648 | 2,147,483,647 | 0 | 4,294,967,296 |

| 64 | -9.223372037×10¹⁸ | 9.223372037×10¹⁸ | 0 | 1.844674407×10¹⁹ |

IEEE754 is a way of representing numerical values in 32- or 64- bits (float or double) so that you don't need to deal with all the fixed point stuff outlined in Fixed Point Math. It does this by using something like Scientific Notation.

But, instead of using base-10, it uses binary. So it has a sign (plus or minus), an exponent (8 bits) and a mantissa (23 bits), or 1/11/52 for double-precision floating pint.

A float value is organized as follows:

SEEEEEEEEMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM

So, for instance, it can represent small numbers with precision, like 0.0001 and 0.00010001, but, if you are using a number like 10000.0, and try to add 0.000001, it will still be 10000.0. This is called 'floating point error'.

It gets worse with bigger numbers, for instance, if you take 16777214.0f (2^24-2), and add 1, you get 16777215.0f, if you add 1 again, you get 16777216.0f, but if you take that and add 1, you still get 16777214.0f. You can add 1 an unlimited number of times, but it will still be the same number. It doesn't increase until you add 2 to it.

Many smaller processors do not have hardware support for floating-ppint, and if you use float on an AVR, it's going to emulate all the float values in software with integer math, which will cause it to go VERY slowly, and use a LOT of flash, one alternative is to use the afore-mentioned Fixed Point Math. And even on processors or systems like GPUs with double prcision hardware, they will run much slower.

BAMs are a way of representing rotations that effectively use natural integer overflows, as well as fully utilizing a binary space, which is great for storing or transmitting rotations. There is no standard for how many bits BAMs use to encode rotation, but using fewer bits will make for chunkier rotations.

The idea is you split a circule of rotation up into equal-rotation segments equal to the number if discrete values your type can represent. For instance, if you made it so you can define 256 unique rotations amounts, you would say the rotation goes from "0 to 255 BAMs".

BAMs work the exact same in signed and unsighed numbers. For instance, a circle from 0 to 255 BAMs if converted to an int8_t would go from -128 to 127 BAMs. Conveniently, wrapping over from 127 to -128 BAMs, the rotation expressed by -128 BAMs is identical to that of 128 BAMs. So you can typecast freely.

Computationally, BAMs are very powerful because normal wrap-around logic, such as given one angle, 15°, what is the difference in angle to 300°? Normally you'd need to check if you wrapped over 360°, then subtract 360°, etc. But with BAMs, you can just subtract, and typecast. Say 15 BAMs to 250 BAMs? (int8_t)(15-250) = 21 or (int8_t)(250-15) = -21.

There are a lot of "rollover" bugs in coding clocks and time deltas, but conveniently, two's complement overflow behavior makes it possible to very easily use, for instance, 32-bit clock timestamps in situations where they will wrap around without any special or tricky handling logic.

This is especially useful in situations with a systick counter likein many ARM and RISC-V processors. Instead of altering the timer value, you can always look relative.

The principle is you use three different types:

typedef int32_t timestamp; // Do this so the default delta behavior is handled well.

typedef int32_t relative_timestamp;

typedef uint32_t elapsed_time; // Used for getting extra headroom, as it can represent a time space of twice as large.Operations you will need to perform:

Check if an event has passed:

timestamp now = GetCurrentTimestamp();

timestamp target_time = some_other_time;

if( now - target_time > 0 )

{

// The event has now passed, do something at this time.

}Get time since an event has happened.

elapsed_time elapsed = GetCurrentTimestamp() - some_other_timestamp;

// elapsed is total time between two eventsTypical rule-of-thumb numbers:

| What | Maximum Represented Delta Time |

|---|---|

| Microseconds, int32_t | 35 minutes |

| Microseconds, uint32_t | 71 minutes |

| Milliseconds, int32_t | 24.85 days |

| Milliseconds, uint32_t | 49.7 days |

| Seconds, int32_t | 68 years Serious issues may happen on January 19, 2038 |

| Seconds, uint32_t | 136 years |

Please note, that if you follow rules above this table, there is no ill effect from wraparound.

And for precision numbers, if you represent a timestamp as a float, after 1.5 days, the time quanta becomes about 10ms.

While historically, the need for multiple charsets was handled by replacing existing charsets, which caused mojibake, in early 1992 UTF-16 was introduced which allowed for the repesentation for many new chars (though it is still limited in implementations that only support UCS-2). This was adopted by platforms such as java, javascript and C# for string representation.

UTF can use variable-length codepoints, where as UCS is fixed-length codepoints. UCS-4 is identical to UTF-32. But, UCS-2 cannot represent as many characters as UTF-16. One other note is some people will convert unicode to UTF-32 or UCS-4 so that it is easier to count characters. Or more specifically, each grapheme.

Wikipedia uses the following string as an example: "ab̲c𐐀" where it uses (U+0332 ̲ COMBINING LOW LINE) to modify "b" as well as an extended char "𐐀". It is 4 characters: a, b̲, c, 𐐀. But, 5 graphemes: a, b, _, c, 𐐀. This means it is represented by 5 unicode code points U+0061, U+0062, U+0332, U+0063, U+10400. If you encode it as UTF-32/UCS-32 using the following codes: 0x00000061, 0x00000062, 0x00000332, 0x00000063, 0x00010400. But it would take six UTF-16 characters to represent: 0x0061, 0x0062, 0x0332, 0x0063, 0xD801, 0xDC00. Or, nine bytes: 0x61, 0x62, 0xCC, 0xB2, 0x63, 0xF0, 0x90, 0x90, 0x80

UTF-8 was developed which allows for treating all strings as strings of 8-bit characters, while representing the whole space. This has unfortunately caused a divergence in computing where many systems continue to use UTF-16 (or UCS-2), instead of UTF-8. UTF-8 can represent regular latin chars as a single-byte. For more exotic characters, it can use multiple bytes to represent all 1,112,064 possible code points.

There is one major note here. With UTF-8, the number of characters represented in a string is different from the naive strlen of a string. For this reason, for dealing with unicode strings, where you care about the number of characters, you will need to use a library like to compute length of string, which can be done using a library like frog_utf.

UTF-8 uses multiple bytes to represent individual code points in the following way (from wikipedia):

| First code point | Last code point | Byte 1 | Byte 2 | Byte 3 | Byte 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U+0000 | U+007F | 0xxxxxxx | N/A | ||

| U+0080 | U+07FF | 110xxxxx | 10xxxxxx | N/A | |

| U+0800 | U+FFFF | 1110xxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | N/A |

| U+010000 | U+10FFFF | 11110xxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx |

In general UTF-8 has few if any serious downsides, and in the opinion of the editor UTF-8 is the only serious contender for charsets moving forward, unless you are specifically operating within a dead ecosystem. There is a more in-depth discussion here: utf8everywhere.org.

- Heap/Stack/Global memory.

- Virtual Clocks

- Sampling Rates / Bandwidth

- Compression Algos (LZSS + Huffman + VPX)

- Maybe something else complex numbers.

- High Level View of Cryptography (Hashing + Signing + ECC/DH + Symmetric)

- https://austinhenley.com/blog/cosine.html

- Complex phasor explaination

- Kicad board layout defaults.

- This Kahan trick for avoiding precision problems with floats: https://pharr.org/matt/blog/2019/11/03/difference-of-floats

- Magnet Wire Bodge Wire Trick

- Useful relationships

- ENOB to bits

- RMS / P-P

- Power

- Capacitance

- Inductance

You don't need to xor by some massive number and shift down, you can just abuse signed math.

For instance with int64_t.

unsigned msb = ((int64_t)value) < 0;There are two common library mechanisms for doing rand. Depending on your system a different one will be more useful than the other: musl rand() change.

static unsigned seed;

int rand(void)

{

return (seed = (seed+1) * 1103515245 + 12345 - 1)+1 & 0x7fffffff;

}vs

static uint64_t seed;

int rand(void)

{

seed = 6364136223846793005ULL*seed + 1;

return seed>>33;

}Be sensitive to consider your architecture specific need here.

Another example is using a Linear Feedback Shift Register to compute random noise, which has some very interesting numerical properties. Such as containing a well behaved pattern that repeats only on the period and only reproduces bit-wise substrings with optimal entropy. It does have one major drawback, in that the data does not appear to be white noise when reading the uint32_t's. While it gives you every one of the 2^32-1 outputs, it will apper correlated.

uint32_t lfsr = 0xACEA1EACU; // Any non-zero start value will do.

void srand( uint32_t s ) { if( !s ) s = 1; lfsr = s; } // State can't be 0.

uint32_t rand()

{

unsigned msb = (int32_t) lfsr < 0;

lfsr <<= 1;

if (msb) lfsr ^= 0x5E000001;

return lfsr;

}Or if you're in a situation where &1 is faster, you can run the LFSR forwards.

uint32_t rand()

{

unsigned lsb = lfsr & 1;

lfsr >>= 1;

if (lsb) lfsr ^= 0x8000007A;

return lfsr;

}Please note, that the individual returned values are heavily correlated, as they are constantly decaying downward. If you want good random data take the LSB of the output of the above function.

For shaders, two great options are hashwithoutsine, the HLSL implementation of it and texture assisted noise from Toocanzs.

First, get the approximate square root from the next power-of-2, then refine it.

int apsqrt( int i )

{

if( i == 0 ) return 0;

int x = 1<<( ( 32 - __builtin_clz(i) )/2);

x = (x + i/x)/2;

// x = (x + i/x)/2; //May be needed depending on how precise you want. (Below graph is without this line)

return x;

}If you need an IIR to compute a high or low-pass filter on your data, here is a solution that gives it to you with just a "running average" state.

This is an IIR filter, which means that as time goes on old values matter less and less.

You will need to tune IIR_AMOUNT to your liking, higher values will be more damped, lower values will be faster to respond.

For removing DC offset, or computing high-pass, take your value, and subtract the filtered value.

#define IIR_AMOUNT 8

static int ifilt; // Accumulates the average.

// Note, the ifilt average will be (1<<IIR_AMOUNT)*average, so

// if IIR_AMOUNT is 8 and you are using values > 255, and ifilt

// is a uint16_t, then, it will OVERFLOW.

int v = rand() % 1000;

ifilt = ifilt + v - (ifilt>>IIR_AMOUNT);

int filtered_value = ifilt>>IIR_AMOUNT;Sometimes if you have a discrete series you may want to find the "center" of a signal causing it. This is particularly useful when looking at DFT bins, a touch sensor. Or, trying to find an impulse. In general this works very well with normal distributions, but can work with any distribution that is symmetric, or even vaguely symmetric.

You can search the list of entries to find the tallest peak, then once found, look at the peak to the left and right. You can then use the following formula to say "The center is d below the highest cell" or "The center is d above the highest cell"

int n = the highest value in a local data set;

float lowercell = data[n-1];

float center = data[n];

float uppercell = data[n+1];

float d = (uppercell-lowercell)*0.5/min( uppercell-center, lowercell-center );So, you want to do math, and you feel like you want to use floating point. Maybe you don't. Fixed point math gives you MORE accuracy with the same number of bits, and in most situations (especially embedded, even when the processor has an FPU) goes faster than floating point math.

Here is a demo program showing many principles of fixed point math:

#include <stdio.h>

void SumDemo()

{

// Assumed a fixed point of 16-bits . 16-bits

int a = 132345; // 2.019424438 (number / 65536 (or 2^16))

int b = 7491; // 0.114303589

int sum = a + b;

printf( "Sum: %f\n", sum/65536.0 ); //2.133728 (correct)

}

void ProductDemoPrecise()

{

// When multiplying fixed point numbers, shift the

// result down by 16 to get your final answer in the

// same fixed-point system you're in.

int a = 132345; // 2.019424438

int b = 7491; // 0.114303589

int product = (a * b + 32768)>>16;

// Adding 32768 fixes rounding, but most of the time you

// don't actually need it.

printf( "Product: %f\n", product/65536.0 ); //0.230820 (correct)

}

void ProductDemoOverflow()

{

int a = 132345; // 2.019424438

int big_b = 4442414; //67.785858154

int product2 = (a * big_b)>>16; // This will overflow.

printf( "Product 2: %f\n", product2/65536.0 ); //-0.111588 (WRONG!)

// At the cost of a tiny bit of imprecision, you can shift down before.

int product3 = (a>>8) * (big_b>>8);

// You can tune where the >>'s go, as long as they add up to 16

// and no one calculation overflows.

printf( "Product 3: %f\n", product3/65536.0 ); //136.629456 (Correct)

}

void FixedNatural()

{

int a = 132345; // 2.019424438

int multiplyby = 18;

int product = a * multiplyby;

//36.349640 (correct)

printf( "Product of Fixed + Natural = %f\n", product / 65536.0 );

}

void Division()

{

// Division is exactly like multiplication just in reverse.

int a = 132345; // 2.019424438

int b = 7491; // 0.114303589

int division = ((a<<12) / (b>>4));

// Try to:

// 1 - avoid overflows

// 2 - maximize the precision of the numerator

// 3 - shifts must add up to 16 (numerator is +, denominator is -)

printf( "Division: %f\n", division/65536.0 ); // 17.674072 (Close)

}

int main()

{

SumDemo();

ProductDemoPrecise();

ProductDemoOverflow();

FixedNatural();

Division();

}A lot of times, you will want to use a sinewave, or need to do DFT for specific tone.

And sin/cos may not be fast. Well, good news, goertzels is to the rescue. You can generate a sin/cos without any sin or cos!

Note that in the below sample, the power will be 0, because the sample is 1.0, so it is treated as a "DC offset" and thus gets nulled out.

Also, goertzels does not need to compute an I and a Q to detect power.

Note that you can store the "coeff" in a table for lookup, it is fixed per the frequency you are observing.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

int main()

{

const float omegaPerSample = 0.015708; // pi / 200

const int numSamples = 400; // enough to go from 0 to 2pi

float coeff = 2 * cos( omegaPerSample );

int i;

// TRICKY: When you want a sinewave, initialize with omegaPerSample. This

// is crucial. The initial state will have massive consequences.

float sprev = omegaPerSample;

float sprev2 = 0;

for( i = 0; i < numSamples; i++ )

{

// If you wanted to do a DFT, set SAMPLE to your incoming sample.

float SAMPLE = 1.0;

// Here is where the magic happens.

float s = SAMPLE + coeff * sprev - sprev2;

sprev2 = sprev;

sprev = s;

printf( "%f\n", s );

}

// For DFT, your power will be:

float power = sprev*sprev + sprev2*sprev2 - (coeff * sprev * sprev2);

printf( "%f\n", power );

}Below is an example using Goertzel's Algorithm to extract the phase and magnitude of a sinewave of an incoming signal, against a specific target frequency. If you think this is magical, that makes two of us.

This is performing a DFT. If all you are looking for is a single value, DFTs are massively faster than FFTs.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

int main()

{

const float omegaPerSample = 0.015708; // pi / 200

const int numSamples = 400; // enough to go from 0 to 2pi

for( float phase = 0; phase < 3.1415926*2.0; phase += 0.01 )

{

float coeff = 2 * cos( omegaPerSample );

int i;

// TRICKY: When you want a sinewave, initialize with omegaPerSample. This

// is crucial. The initial state will have massive consequences.

float sprev = omegaPerSample;

float sprev2 = 0;

for( i = 0; i < numSamples; i++ )

{

// If you wanted to do a DFT, set SAMPLE to your incoming sample.

float SAMPLE = sin( phase + i * omegaPerSample );

// Here is where the magic happens.

float s = SAMPLE + coeff * sprev - sprev2;

sprev2 = sprev;

sprev = s;

}

// For DFT, your power will be:

float power = sprev*sprev + sprev2*sprev2 - (coeff * sprev * sprev2);

//printf( "Power: %f\n", power );

float coeff_s = 2 * sin( omegaPerSample );

double rR = 0.5 * coeff * sprev - sprev2;

double rI = 0.5 * coeff_s * sprev;

printf( "%f,%f\n", rR, rI);

}

}Use the following command:

coredumpctl gdb

btTo get a backtrace of the most recently crashed program.

gdb --args ./my_program my_argumentsUse strace, you can start it like strace {command} - and it will then output a summary of all system calls to >2.

You can connect strace to an already running process with strace -p {pid number} -f

Use screen (or tmux, but I prefer screen).

screen command-line or screen bash then run your command. Or if you just want to launch it and forget it, i.e. if using /etc/rc.local then use screen -AmdS screen_name comamnd.

To detach from inside a screen, ctrl+a then ctrl+x, to exit, ctrl+a then ctrl+k.

To re-attach to a screen that is running use screen -x - if there are multiple screens, you can use screen -x screen_name note that you can partial match screen_name

A basic Makefile would be:

all : test

test : test.c

gcc -o test test.c

clean :

rm -rf testMakefiles are just:

thing_you_make : things needed to make it

commands you execute to

make the thingThere are some shortcuts in Makefiles. Like:

$@replace withthing_you_make$^replace withthings needed to make it$<replace withthings(or the first thing in the things needed).

That's honestly all you need to know for now.

From from @OwenTheProgrammer, "My makefile doesnt recompile if I save header files!"

# Get all the header files

INC_FILES = $(wildcard $(INC_DIR)/*.h)

# And add them to some dependency list

something: ... $(INC_FILES)You have to make a syscall, but you can use inline assembly to wrap it so that it doesn't have to spend time/effort getting the registers setup correctly.

Be sure to compile with: gcc -Os -nostdlib -Wl,-e"start" -ffunction-sections -fdata-sections -flto -Wl,--gc-sections for optimal behavior, also set start to be your start function.

#include <asm/unistd.h> // compile without -m32 for 64 bit call numbers

// In x86_64 only.

// call write( int fd, uint8_t ptr, int length )

asm volatile

(

"syscall"

: "=a" (ret)

// EDI RSI RDX

: "0"(__NR_write), "D"(/*fd*/fd), "S"(ptr), "d"(length)

: "rcx", "r11", "memory"

);Lastly don't forget to exit!

asm volatile

(

"syscall"

: "=a" (r)

// EDI

: "0"(__NR_exit), "D"(/*fd*/0), "S"(0), "d"(0)

: "memory"

);Because smaller capacitors many times will have much, much lower capacitance once you put a DC voltage (bais) across them.

And they typically have much better current carrying + lower ESR.

Find your specific capacitor here, to get all the data on it. While this link is for Samsung, most capacitor manufacturers have similar properties.