const car = {

numberOfDoors: 4,

drive: function () {

console.log(`Get in one of the ${this.numberOfDoors} doors, and let's go!`);

}

};

const letsRoll = car.drive;

letsRoll();Answer : this refers to the window object

Explanation : The Window Object

This object is provided by the browser environment and is globally accessible to your JavaScript code using the identifier, window. This object is not part of the JavaScript specification (i.e., ECMAScript); instead, it is developed by the W3C.

Since the window object is at the highest (i.e., global) level, an interesting thing happens with global variable declarations. Every variable declaration that is made at the global level (outside of a function) automatically becomes a property on the window object

Similarly to how global variables are accessible as properties on the window object, any global function declarations are accessible on the window object as methods:

function learnSomethingNew() {

window.open('https://www.udacity.com/');

}

window.learnSomethingNew === learnSomethingNew

// trueDeclaring the learnSomethingNew() function as a global function declaration

(i.e., it's globally accessible and not written inside another function) makes it accessible to your code as either learnSomethingNew() or window.learnSomethingNew().

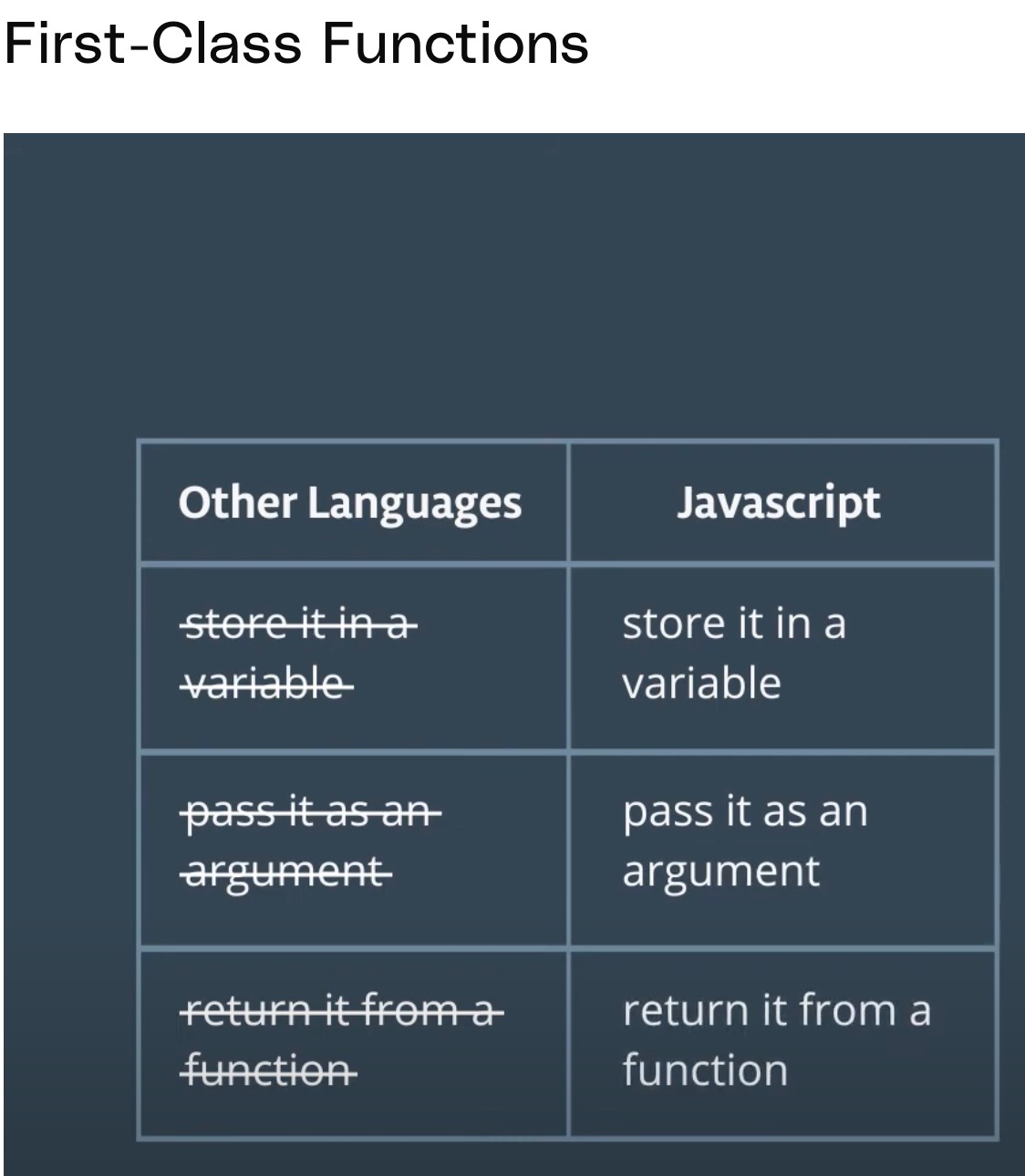

If a programming language has

first class functionthen ,in that language a function has equal status to any other data structure eg : string , int , boolean etc ...

This means that you can do with a function just

about anything that you can do with other

elements, such as numbers, strings,

objects, arrays, etc. JavaScript functions

can

1. Be stored in variables

2. Be returned from a function.

3. Be passed as arguments into another function.

A function that returns another function is known as higher-order function. Consider this example:

function alertThenReturn() {

alert('Message 1!');

return function () {

alert('Message 2!');

};

}Since alertThenReturn() returns that inner function, we can assign a variable to that return value

const innerFunction = alertThenReturn();

We can then use the innerFunction variable like any other function!

innerFunction(); // alerts 'Message 2!'

Likewise, this function can be invoked immediately without being stored in a variable. We'll still get the same outcome if we simply add another set of parentheses to the expression

alertThenReturn();:

alertThenReturn()();

// alerts 'Message 1!' then alerts 'Message 2!'A function that is passed as an argument into another function is called a callback function.

A JavaScript closure makes it possible for a function to have "private" variables.

const myName = 'Andrew';

function introduceMyself() {

const you = 'student';

function introduce() {

console.log(`Hello, ${you}, I'm ${myName}!`);

}

return introduce();

}

introduceMyself();

// 'Hello, student, I'm Andrew!'

// this closure retails the scope of it's

// creation i.e where myName = 'Andrew'

// in global scopeWe know that the variables of a parent function are accessible to the nested, inner function. If the nested function captures and uses its parent's variables (or variables along the scope chain, such as its parent's parent's variables), those variables will stay in memory as long as the functions that utilize them can still be referenced.

function myCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function () {

count += 1;

return count;

};

}

/*The existence of the nested function

keeps the count variable from being

available for garbage collection,

therefore count remains available

for future access.*/We need to be super cautious while creating closures because all the reference variables of that closure's scope will not be garbage collected till you are using it i.e , till there is a reference to that closure

A function that is called immediately after it is defined

-

One of the primary uses for IIFE's is to create private scope (i.e., private state).

-

Because the function expressed is called immediately, the IIFE wraps up the code nicely so that we don't pollute the global scope.`

-

If you simply have a one-time task (e.g., initializing an application), an IIFE is a great way to get something done without polluting your the global environment with extra variables.`

Ex 1:

(function (name){

alert(`Hi, ${name}`);

}

)('Andrew');

//// alerts 'Hi, Andrew'

-------------------------------------

Ex 2 :

(function (x, y){

console.log(x * y);

}

)(2, 3);

// 6The second pair of parentheses not only immediately executes the function preceding it -- it's also the place to put any arguments that the function may need!

We pass in the string 'Andrew', which is stored in the function expression's name variable. It is then immediately invoked, alerting the message 'Hi, Andrew' onto the screen.

Again , in Ex 2: -- the arguments passed into the anonymous function (i.e., 2 and 3) belong in trailing set of parentheses.

Say that we want to create a button on a page that alerts the user on every other click. One way to begin doing this would be to keep track of the number of times that the button was clicked. But how should we maintain this data? We could keep track of the count with a variable that we declare in the global scope (this would make sense if other parts of the application need access to the count data). However, an even better approach would be to enclose this data in event handler itself!

For one, this approach prevents us from polluting the global with extra variables (and potentially variable name collisions). What's more: if we use an IIFE, we can leverage a closure to protect the count variable from being accessed externally! This prevents any accidental mutations or unwanted side-effects from inadvertently altering the count.

<html>

<body>

<button id="button">

Click Me

</button>

<script src="button.js"> </script>

</body>

</html>const button = document.getElementById('button')

button.addEventListener('click',(function(){

let count =0;

return function(){

count++;

alert("The count is " + count)

}

})())-

These are special functions that are called before the creation of a new class.

-

They do not need to return the reference to the object , as it's done automatically in this special function

Eg :

function SoftwareDeveloper() {

this.favoriteLanguage = 'JavaScript';

}

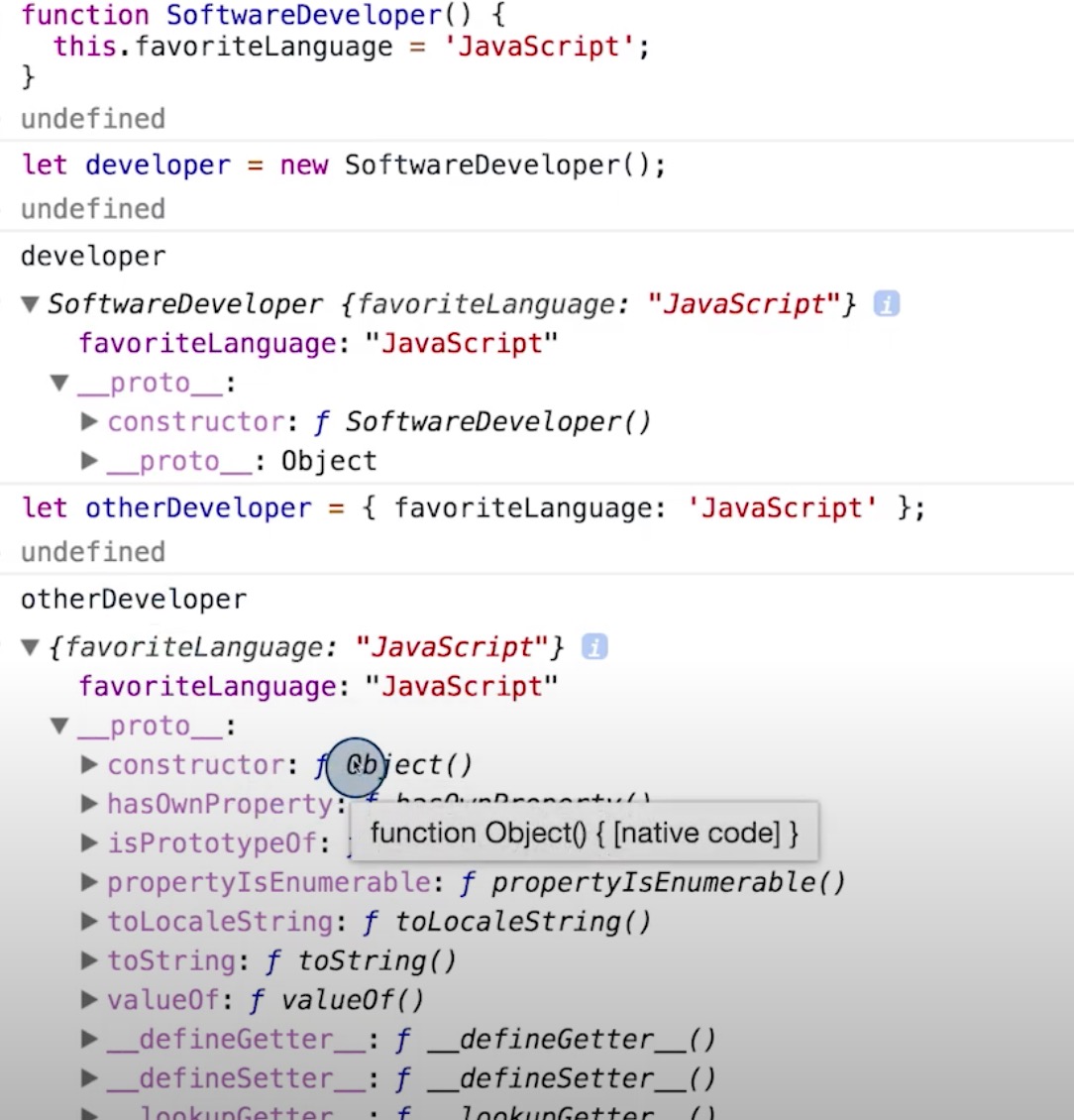

- In the previous code , theSoftwareDeveloper function is a

constructor function, which is not returning anything , but when called with new , it returns the reference to a newly created object withfavoriteLanguage as Javascript

const developer =new SoftwareDeveloper()

// here , developer has access to the

// current objectDifference between an object created using a constructor function vs one created using the object literal notation

The constructor of the object literal is Object , whereas that of the one using the constructor function , is the name of the constructor

Capitalizing the first letter of a constructor function's name is just a naming convention. Though the first letter should be capitalized, inadvertently leaving it lower-cased still makes the constructor function (i.e., when invoked with the new operator, etc.).

i .e :

function softwareDeveloper() {

this.favoriteLanguage = 'JavaScript';

}

const developer = new softwareDeveloper();

console.log(developer.favoriteLanguage)

console.log(developer)

// this still works the same waywhen invoking a constructor function with the new operator,

thisgets set to the newly-created object

function Cat(name) {

this.name = name;

this.sayName = function () {

console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`);

};

}

const bailey = new Cat('Bailey');

----

Actual Object Created :

{

name: 'Bailey',

sayName: function () {

console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`);

}

}when you say this in a method, what you're really saying is "this object" or "the object at hand.

-

First, calling a constructor function with the new keyword sets this to a newly-created object

function Cat(name) { this.name = name; this.sayName = function () { console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`); }; } const bailey = new Cat('Bailey'); ---- Actual Object Created : { name: 'Bailey', sayName: function () { console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`); }}

-

On the other hand, calling a function that belongs to an object (i.e., a method) sets this to the object itself

const dog = { bark: function () { console.log('Woof!'); }, barkTwice: function () { this.bark(); this.bark(); } }; -

Third, calling a function on its own (i.e., simply invoking a regular function) will set this to window, which is the global object if the host environment is the browser.

function funFunction() { return this; } funFunction(); // (returns the global object, `window`)

-

The fourth way to call functions, allows us to set

thisourselves using

-

Call - This is called on a function, where the first argument is the thing you want this to be bound to and the next few arguments are the original argument variables of the function that are to be called

Eg 1 : function add(a,b){ return a+b } const result = add.call(this,2,4) // 6 Here ,the first argument is the context of this, the second and third arguments are the args that the function was called with ---- Eg 2 : Using call() to invoke a method allows us to "borrow" a method from one object -- then use it for another object const mockingbird={ title:"To kill a Mockingbird", describe:function(){ console.log(` ${this.title} is a classic novel`) } } mockingbird.describe() // Result : To kill a Mockingbird is a classic novel const harrypotter={ title:"Harry Potter" } mockingbird.describe .call(harrypotter) Result : Harry Potter is a classic novel Here, using call , we can see that we changed the context of this to the harrypotter object , instead of the mockingbird object where it was originally created -

Apply ( )

The apply() method does the same this as the call method, albeit with differences in how arguments are passed into it.

Eg:

So, when to use apply over call ?

function add(a,b){ return a+b } const result = add .apply(this,[2,4]) //the only difference using call is , //that we're passing args in an array //rather than individually

call() may be limited if you don't know ahead of time the number of arguments that the function needs. In this case, apply() would be a better option, since it simply takes an array of arguments, then unpacks them to pass along to the function.

-

Bind :

bind() returns a new function that, when called, has this set to the value we give it.

This is generally used when you want to pass a function as a callback function , and you want to explicitly define what

thiswould be referring to when calling the callback function.Click to see Example of Using Bind

// bind() returns a new function that, when called, has this set to the value we give it.

const dog={ age :5, growOneYear:function(){ this.age++; } } function invokeTwice(cb) { cb() cb() } //invokeTwice(dog.growOneYear) // this will not increment the dog's age // as this will be bound to the global object, // as the state was not preserved // invokeTwice(function() { // dog.growOneYear(); // }) // In the previous case , the closure captures // the State , because of which growOneYear // will be bound to the dog object const bound = dog.growOneYear.bind(dog) // Here the function's context i.e this is // explicitly bound to the dog object invokeTwice(bound) console.log("Dog's age is",dog.age) const driver = { name: 'Danica', displayName: function () { console.log(`Name: ${this.name}`); } }; const car = { name: 'Fusion' }; const driverBound= driver.displayName.bind(car) invokeTwice(driverBound)

-

function Cat(name) {

this.lives = 9;

this.name = name;

this.sayName = function () {

console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`);

};

}

In this example , you're attaching the

sayName function to the constructor function,

so every object created using new Cat() ,

will have a new sayName function created for it.If we attach the same ,

sayNamefunction to the prototype of cat , then all objects created using cat , will have reference to the same function, hence the space for a new function will be saved , plus DRY principle will be followed.

Along with being more efficient, we also don't have to update all objects individually should be decide to change a method.

function Cat(name) {

this.name=name;

}

Cat.prototype.sayName=function () {

console.log(`Meow! My name is ${this.name}`);

};In this example , you're attaching the

sayName function to the constructor function,

so every object created using new Cat() ,

will have a new sayName function created for it.

const myCat = new Cat();

print(myCat)

this will not have sayName() function defined. As it's attached to the prototype, and not this specific object

JavaScript interpreter looks for them along the prototype chain in a very particular order:

- First, the JavaScript engine will look at the object's own properties. This means that any properties and methods defined directly in the object itself will take precedence over any properties and methods elsewhere if their names are the same (similar to variable shadowing in the scope chain).

- If it doesn't find the property in question, it will then search the object's constructor's prototype for a match.

- If the property doesn't exist in the prototype, the JavaScript engine will continue looking up the chain.

- At the very end of the chain is the Object() object, or the top-level parent. If the property still cannot be found, the property is undefined.

hasOwnProperty() allows you to find the origin of a particular property

Upon passing in a string of the property name you're looking for, the method will return a boolean indicating whether or not the property belongs to the object itself (i.e., that property was not inherited)

function Phone() {

this.operatingSystem = 'Android';

}

Phone.prototype.screenSize = 6;

----------------------------------------------------------------

const myPhone = new Phone();

const own = myPhone.hasOwnProperty('operatingSystem');

console.log(own);

// true

----------------------------------------------------------------

What about the screenSize property,

which exists on Phone objects'

prototype?

const inherited = myPhone.hasOwnProperty('screenSize');

console.log(inherited);

// falseObjects also have access to the isPrototypeOf() method, which checks whether or not an object exists in another object's prototype chain.

Using this method, you can confirm if a particular object serves as the prototype of another object.

If the prototype of an object is unknown , then to get the prototype of an object , you use this function

See isPrototypeOf and getPrototypeOf in Action

Each time an object is created, a special property is assigned to it under the hood: constructor

function Longboard() {

this.material = 'bamboo';

}

const board = new Longboard();

If we access board's

constructor property,

we should see the

original constructor

function itself:

console.log(board.constructor);

// function Longboard() {

// this.material = 'bamboo';

// }But when we create an object using the literal

notation , then the constructor is always Object

const rodent = {

favoriteFood: 'cheese',

hasTail: true

};

console.log(rodent.constructor);

// function Object() { [native code] }

--- pending ---