The Parser Construction Kit is a parser generator that targets the .NET platform, and is written in C#. It was designed with C# in mind. It can use the Microsoft CodeDOM to render parsers in other .NET languages and bits v0.0.1.8 and above should support VB particularly.

PCK has tools to cover three major parsing paradigms:

- LL(1) parsers: The preferred parsing mechanism if it will meet the requirements necessary.

- LALR(1) parsers: A more powerful parser that accepts more grammars, but with some drawbacks compared to LL(1), such as additional complexity, and lack of error recovery and continuation due to the nature of the algorithm.

- Hand written parsers, since these are so often useful in small doses. It would be extremely heavy handed to, for example, parse an integer using an entire context free grammar!

The runtime library required to use the generated parsers, called simply pck (pck.dll) is a small library that provides support for generated LL(1) and LALR(1) parsers, as well as support for hand written parsers using the ParseContext class.

The assorted tools that come with pck can be used for parser and lexer/tokenizer generation.

It can generate FA based lexers/tokenizers and PDA based parsers on the LL(1) algorithm, with an eye toward supporting LL(1) conflict resolution in the future. It can generate LALR(1) parsers based on an LALR(1) via SLR(1) translation. It can easily be extended to support LR(0), perhaps LR(1) and SLR(1) down the road, if desired.

Install simply by taking the binaries and putting them somewhere in your path, or just navigating to that folder whenever you want to use them. Note that pckedit will automatically register itself with .xbnf and .pck extensions, and with the shell on the first time it is run, so it doesn't need to be in the path. If you never want to use the commandline, you don't have to set up the paths.

To keep them up to date, simply close all PCK programs, navigate to the folder where your binaries are - this is required regardless of your PATH variable, and then type pckver /update

You'll want to decide carefully which parser best meets your needs before you begin.

-

Use the LL(1) parser if your grammar can be recognized by it, or unless you're building a hand rolled parser The LL(1) parser is the most flexible and potentially the fastest generated parser, depending on what you're doing. It's also the easiest to use overall, although there's not a lot of difference between the generated parsers in use. Its main drawback is the limited subset of CFG grammars it can support.

-

Use the LALR(1) parser if you need greater power in terms of what your grammars can do. It can be a little more complicated if you're not using the parse tree, but rather the reader directly, though most people won't unless they need to stream. Its main limitation is error recovery. Currently it can't do it, and it will never be as good as the LL(1) error recovery even if it could, because of the way the algorithm works.

-

Use handrolled parsers either for very simple grammars where generated parsers won't really save you time, or for grammars where you need the greatest flexibility and CFG grammars just won't cut it. Its main limitation for anything other than trivial grammars is maintenance and increased potential for bugs.

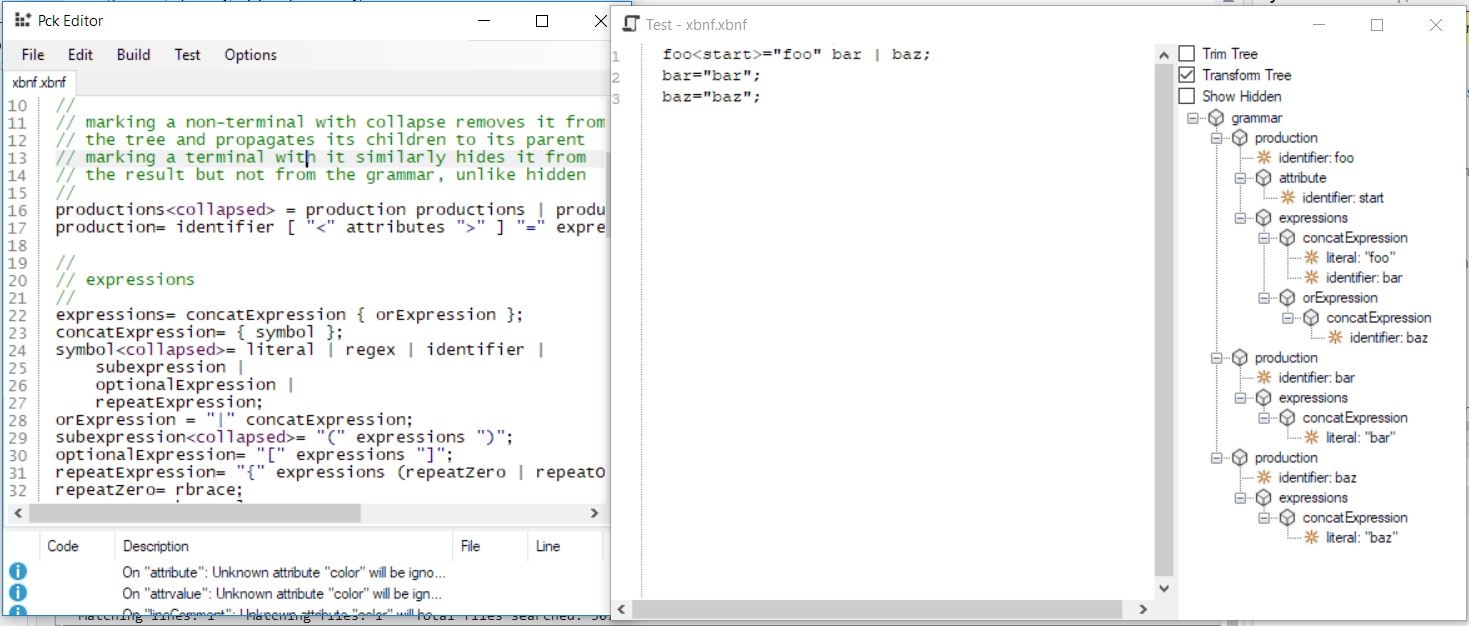

By far, the simplest way to generate a parser on a Windows OS is to use pckedit and create an XBNF grammar, then test or build the parser using the menus.

pckedit is a windows application that acts as a multiple document container for XBNF, pck, and other files, with syntax highlighting. It has menus for code generation and for testing grammars, but otherwise works a lot like notepad++. The menus operate on the current active document so be mindful of that if your menus are grayed. For example, it won't let you turn a PCK spec file into another PCK spec file, nor will it let you build/generate code from anything other than an XBNF or PCK file. Below the documents is a list of warnings and errors for the last operation. The test menu allows you to test your grammars with LL(1) and LALR(1) parsers without generating code. Generation does not create files. Files must be saved explicitly in order to be stored, unlike visual studio, for example.

Aside from pckedit, pckw and pckp (DF and Core versions of the same app, with identical functionality) provide an extensive set of operations available at the command line, including grammar transformation, exporting, and code generation for both types of parser, and for tokenizers.

PCK is designed to let you work with different parser generator tools as well.

The "XBNF" grammar format can be used to construct grammars to pass to parser generators, including YACC, with an extensible translation feature that allows for creation of future grammar and lexer file transformations.

Here's the Pckw/Pckp utility usage screen, which breaks up the different parser / lexer generator tasks into console accessible operations

They're each different builds of the same executable, although Pckw is the windows version, and Pckp is the .NET core version. Functionally they are identical.

Usage: pckw <command> [<arguments>]

Commands:

pckw fagen [<specfile> [<outputfile>]] [/class <classname>] [/namespace <namespace>] [/language <language>]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use (or stdin)

<outputfile> The file to write (or stdout)

<classname> The name of the class to generate (or taken from the filename or from the start symbol of the grammar)

<namespace> The namespace to generate the code under (or none)

<language> The .NET language to generate the code for (or draw from filename or C#)

Generates an FA tokenizer/lexer in the specified .NET language.

pckw ll1gen [<specfile> [<outputfile>]] [/class <classname>] [/namespace <namespace>] [/language <language>]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use (or stdin)

<outputfile> The file to write (or stdout)

<classname> The name of the class to generate (or taken from the filename or from the start symbol of the grammar)

<namespace> The namespace to generate the code under (or none)

<language> The .NET language to generate the code for (or draw from filename or C#)

Generates an LL(1) parser in the specified .NET language.

pckw ll1factor [<specfile> [<outputfile>]]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use (or stdin)

<outputfile> The file to write (or stdout)

Factors a pck grammar spec so that it can be used with an LL(1) parser.

pckw ll1tree <specfile> [<inputfile>]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use

<inputfile> The file to parse (or stdin)

Prints a tree from the specified input file using the specified pck specification file.

pckw lalr1gen [<specfile> [<outputfile>]] [/class <classname>] [/namespace <namespace>] [/language <language>]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use (or stdin)

<outputfile> The file to write (or stdout)

<classname> The name of the class to generate (or taken from the filename or from the start symbol of the grammar)

<namespace> The namespace to generate the code under (or none)

<language> The .NET language to generate the code for (or draw from filename or C#)

Generates an LALR(1) parser in the specified .NET language.

pckw lalr1tree <specfile> [<inputfile>]

<specfile> The pck specification file to use

<inputfile> The file to parse (or stdin)

Prints a tree from the specified input file using the specified pck specification file.

pckw xlt [<inputfile> [<outputfile>]] [/transform <transform>] [/assembly <assembly>]

<inputfile> The input file to use (or stdin)

<outputfile> The file to write (or stdout)

<transform> The name of the transform to use (or taken from the input and/or output filenames)

<assembly> The assembly to reference

Translates an input format to an output format.

Available transforms include:

cgtToPck Translates a Gold Parser cgt file into a pck spec. (requires manual intervention)

pckToLex Translates a pck spec to a lex/flex spec. (requires manual intervention)

pckToYacc Translates a pck spec to a yacc spec

xbnfToPck Translates an xbnf grammar to a pck spec.

so - if you want to take an XBNF document

like this

productions<collapsed> = production productions | production;

production= identifier [ "<" attributes ">" ] "=" expressions ";";

expressions<collapsed>= expression { "|" expression };

expression= { symbol };

symbol= literal | regex | identifier |

"(" expressions ")" |

"[" expressions "]" |

"{" expressions ("}"|"}+");

...

and turn into a pck spec (which you have to do before you can do much else with it)

productions:collapsed

expressions:collapsed

symbollist:collapsed

attributelisttail:collapsed

grammar-> productions

productions-> production productions

productions-> production

production-> identifier lt attributes gt eq expressions semi

production-> identifier eq expressions semi

expressions-> expression expressionlisttail

expressions-> expression

expression-> symbollist

expression->

symbol-> literal

symbol-> regex

symbol-> identifier

symbol-> lparen expressions rparen

symbol-> lbracket expressions rbracket

symbol-> lbrace expressions rbrace

symbol-> lbrace expressions rbracePlus

...

you'd use the command line like

pckw xlt xbnf.xbnf xbnf.pck

now, before you can use it with an LL(1) parser (including Pck's, or say Coco/R) you have to "factor" it

from the command line

pckw ll1factor xbnf.pck xbnf.ll1.pck

you can then generate the code for it or export it whatever you like

pckw fagen xbnf.ll1.pck XbnfTokenizer.cs

pckw ll1gen xbnf.ll1.pck XbnfParser.cs

or you can pipe these operations. Like, turn an xbnf grammar into a parser:

pckw xlt xbnf.xbnf /transform xbnfToPck | pckw ll1factor | pckw ll1gen /class XbnfParser > XbnfParser.cs

There's an api for building additional xlt transformations. They're relatively easy to implement, considering. Right now it's just lex and yacc, and partially Gold.

The Gold lexer transformations won't happen until I can implement arden's theorem in c# (any help?)

The XBNF format is designed to be easy to learn if you know a little about composing grammars.

The productions take the form of

identifier [ < attributes > ] = expressions

So for example here's a simple "compliant enough" json grammar that's more than suitable for a tutorial

json<start>= object | array;

object= "{" "}" | "{" fields "}";

fields<collapsed>= field | field "," fields;

field= string ":" value;

array= "[" "]" | "[" values "]";

values<collapsed>= value | value "," values;

value= string | number | object | array | boolean | null;

boolean= true|false;

// terminals

number= '\-?(0|[1-9][0-9]*)(\.[0-9]+)?([Ee][\+\-]?[0-9]+)?';

// below: string is not compliant, should make sure the escapes are valid JSON escapes rather than accepting everything

string = '"([^"\\]|\\.)*"';

true="true";

false="false";

null="null";

lbracket<collapsed>="[";

rbracket<collapsed>="]";

lbrace<collapsed>="{";

rbrace<collapsed>="}";

colon<collapsed>=":";

comma<collapsed>=",";

whitespace<hidden>='[ \t\r\n\f\v]+';

The first thing to note is the json production is marked with a start attribute. Since the value was not specified it is implicitly, start=true

That tells the parser that json is the start production. If it is not specified the first non-terminal in the grammar will be used. Furthermore, this can cause a warning during generation since it's not a great idea to leave it implicit. Only the first occurance of start will be honored

object | array tells us the json production is derived as an object or array.

The object production contains several literals and a reference to fields

-

( )parentheses allow you to create subexpressions likefoo (bar|baz) -

[ ]optional expressions allow the subexpression to occur zero or once -

{ }this repeat construct repeats a subexpression zero or more times -

{ }+this repeat construct repeats a subexpression one or more times -

|this alternation construct derives any one of the subexpressions -

Concatenation is implicit, separated by whitespace

The terminals are all defined at the bottom but they can be anywhere in the document. XBNF considers any production that does not reference another production to be a terminal. This is similar to how ANTLR distinguishes the terminals in its grammar.

Regular expressions are between ' single quotes and literal expressions are between " double quotes. You may declare a terminal by using XBNF constructs or by using regular expressions. The regular expressions follow a POSIX + std extensions paradigm but don't currently support all of POSIX. They support most of it. If a POSIX expression doesn't work, consider it a bug.

The collapsed element tells Pck that this node should not appear in the parse tree. Instead its children will be propagated to its parent. This is helpful if the grammar needs a nonterminal or a terminal in order to resolve a construct, but it's not useful to the consumer of the parse tree. During LL(1) factoring, generated rules must be made, and their associated non-terminals are typically collapsed. Above we've used it to significantly trim the parse tree of nodes we won't need including collapsing unnecessary terminals like : in the JSON grammar. This is because they don't help us define anything - they just help the parser recognize the input, so we can throw them out to make the parse tree smaller. The LL(1) parser can remove collapsed nodes during the underlying read if ShowCollapsed is set to false. This can significantly speed up parsing for large documents with lots of collapsed nodes. This performance feature is unavailable in the other parsers, but the parse trees they generate will have the collapsed nodes removed.

The hidden element tells Pck that this terminal should be skipped. This is useful for things like comments and whitespace. Hidden terminals can be shown if the parser has ShowHidden set to true, if the presence or location of comments is neede during a parse for example.

The blockEnd attribute is intended for terminals who have a multi character ending condition like C block comments, XML CDATA sections, and SGML/XML/HTML comments. If present the lexer will continue until the literal specified as the blockEnd is matched.

The terminal attribute declares a production to be explicitly terminal. Such a production is considered terminal even it it references other productions. If it does, those other productions which will be included in their terminal form as though they were part of the original expression. This allows you to create composite terminals out of several terminal definitions.

Other attributes can be applied, but they will be ignored. They can be retrieved however, during the parsing process using GetAttribute, as the parser exposes them.

Consider the following simple expression grammar, expr.xbnf:

expr = expr "+" term | term;

term= term "*" factor | factor;

factor= "(" expr ")" | int;

add="+";

mul="*";

lparen="(";

rparen=")";

int= '[0-9]+';

Generate a parser

pckw xlt expr.xbnf /transform xbnfToPck | pckw ll1factor | pckw ll1gen /class ExprParser /namespace Demo > ExprParser.cs

Generate a tokenizer

pckw xlt expr.xbnf /transform xbnfToPck | pckw ll1factor | pckw fagen /class ExprTokenizer /namespace Demo > ExprTokenizer.cs

What we just did is take the XBNF, turn it into a PCK spec, factor it, and then generate code from it (twice) We have to factor it for the tokenizer as well or the symbols in the parser and tokenizer won't match up so we do it both times.

Now, create a new .NET console project, add a reference to pck, add the two newly generated files, and reference the Demo namespace in your using directives

In theMain() function write

var parser = new ExprParser(new ExprTokenizer("3*(4+7)"));

This will get you a new parser and tokenizer over the expression 3*(4+7)

A note about parsing from files and streaming sources:

The tokenizers expect IEnumerable<char> which is great if you have a string or a char array, but TextReader does not expose one. Simply use the FileReaderEnumerable, ConsoleReaderEnumerable or UrlReaderEnumerable to read input from one of the three sources or expose IEnumerable<char> from the source yourself. The prior classes capture input from a file, the console stdin or an URL, respectively, and make it simple to foreach repeatedly over the characters therein. That's the ideal. Sometimes you can't repeat an enumeration, and it's okay to throw in an implementation that doesn't support it, such as a non-seekable stream with no "getter" method to refetch the stream, like the console.

So for example:

var parser = new ExprParser(new ExprTokenizer(new ConsoleReaderEnumerable()))

would pull from stdin, but the parser won't consider itself done until you hit ctrl-Z which is the console signal for end of input.

var parser = new ExprParser(new ExprTokenizer(new FileReaderEnumerable(@"myexpr.txt")))

would pull from "myexpr.txt" in the current working directory.

As far as lifetime, there is no need to close these explicitly, as they only hold the stream for the duration of the enumerator lifetime. Their enumerators must be disposed of with Dispose() or you risk leaving a stream open and possibly locked. foreach will do this automatically, as will the parser class and tokenizer class where appropriate so you don't have to worry about it as long as you call Close() or otherwise dispose of the parser itself.

Anyway, moving on, there are a couple of ways from here in which you can use the parser, wherever your input comes from.

If you want streaming access to the pre-transformed parse tree, you can call the parser's Read() method in a loop, very much like Microsoft's XmlReader:

while(parser.Read())

{

switch(parser.NodeType)

{

case LLNodeType.Terminal:

case LLNodeType.Error:

Console.WriteLine("{0}: {1}",parser.Symbol,parser.Value);

break;

case LLNodeType.NonTerminal:

Console.WriteLine(parser.Symbol);

break;

}

}

A lot of times that's not what you want though. You want a parse tree, and you want the collapsed nodes and such to be gone.

So instead of the above, you can use

var tree = parser.ParseSubtree(); // pass true if you want the tree to be trimmed.

// write an ascii tree

Console.WriteLine(tree); // calls tree.ToString()

tree and each of its nodes contains all of the information about the node at that position in the parse.

Generating and using the LALR(1) parser is very similar:

Generate a parser

pckw xlt expr.xbnf /transform xbnfToPck | pckw lalr1gen /class ExprParser /namespace Demo > ExprParser.cs

Generate a tokenizer

pckw xlt expr.xbnf /transform xbnfToPck | pckw fagen /class ExprTokenizer /namespace Demo > ExprTokenizer.cs

Note that we didn't factor the grammar since there is no need to do so with LALR(1)

And now, almost like before:

while(parser.Read())

{

switch(parser.NodeType)

{

case LRNodeType.Shift:

case LRNodeType.Error:

Console.WriteLine("{0}: {1}",parser.Symbol,parser.Value);

break;

case LRNodeType.Reduce:

Console.WriteLine(parser.Rule);

break;

}

}

or

var tree = parser.ParseReductions(); // pass true if you want the tree to be trimmed.

Console.WriteLine(tree);

If you've ever tried to use TextReader or IEnumerator<char> to parse a document, you've probably run into these common frustrations: The enumerator doesn't have a way to check if you're at the end of the enumeration after-the-fact, and the text reader's Peek() function is unreliable on certain sources, like NetworkStream. Both of these limitations require extra bookkeeping to overcome, complicating the parsing code and distracting from the core responsibility - parsing some input!

Another significant limitation is lack of lookahead. You can peek at the one character in front of you and that's it, typically, but sometimes, you just need to look ahead further to complete a parse.

There's also nothing to help with error handling and reporting during a parse.

ParseContext can help with all of this, plus has a number of useful helpers for skipping over whitespace and comments, parsing numbers and strings, etc.

ParseContext works quite a bit like TextReader in that it returns input characters as an int. It signals end of input with -1. Unlike the TextReader, it also signals before start of input with -2, and disposed with -3.

Advance() works like the Read() function does on the TextReader class. It advances the input by one character and returns the result as an int.

However, we'll most often be getting our current character from the Current property, which is an int that always holds the character under the cursor (or one of the negative number signals as outlined above) while simply using Advance() to move through the text. Either one works fine. Use whichever suits you in the moment.

To peek ahead in the input without advancing the cursor, we have the Peek() method which takes an optional int lookAhead parameter that indicates how many characters to look forward. Specifying zero simply retrieves the character under the cursor. In any case, the cursor position remains unchanged. This method is safe for non-seekable sources like NetworkStream.

For tracking the position of the input cursor, we have Line, Column, Position, and TabWidth. The first three report the location of the cursor while the latter should be set to the width of the tab on the input device. Doing so ensures that Column will be reported properly in the even of a tab. The default is 8, and they work like tab stops do on a console window, with the screen laid out in virtual columns, meaning an actual tab isn't always the same number or "spaces".

For error reporting, we have the Expecting() method which takes a variable list of arguments that represent the list of inputs allowed to be present under the cursor. This can include -1 to signify that end of input is one of the allowable values, while passing no parameters is a way to indicate that anything except end of input will be accepted. In the event that the current character is not accepted, an ExpectingException is thrown that reports a detailed error message.

We have an internal capture buffer based around a StringBuilder which we can use to hang on to the input we've parsed so far. This is represented by the CaptureBuffer property. On the ParseContext, we also have CaptureCurrent() which captures the current character under the cursor, if there is one, ClearCapture() which clears the capture buffer, and GetCapture() which retrieves all or part of the capture buffer as a string.

For creating the ParseContect, we have several static methods: the Create() method which takes a string or a char array, CreateFrom() which takes a filename or a TextReader and CreateFromUrl() which takes a string URL.

Remember that ParseContext implements IDisposable and it's very important to dispose of it when one is finished if one loaded text from anything other than a string or a char array. A Close() method would be the usual way to do so but I removed it because there are too many members that start with "C" and it was making intellisense arduous. Use Dispose() or the using keyword in C#.

In addition, ParseContext includes several helpers including TrySkipWhitespace(), TryReadUntil() and various other methods for common parsing tasks - even parsing JSON.

For the purpose of this demonstration, we'll reimplement the JSON parsing.

The JSON grammar is pretty simple, and you can see all the particulars at https://json.org.

The parsing implementation is below. Roughly, it's divided into 3 major parts to represent the major components of a JSON tree: A JSON object, a JSON array, and a JSON value.

Notice how easily one can call subfunctions in this parse without having to worry about transferring the current character - something that's difficult to do with an enumerator or a text reader. Overall, this leads to much cleaner separation of the various parsing functions, and an easier time writing them. The comments should explain the particulars:

static object _ParseJson(ParseContext pc)

{

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

switch(pc.Current)

{

case '{':

return _ParseJsonObject(pc);

case '[':

return _ParseJsonArray(pc);

default:

return _ParseJsonValue(pc);

}

}

static IDictionary<string, object> _ParseJsonObject(ParseContext pc)

{

// a JSON {} object - our objects are dictionaries

var result = new Dictionary<string, object>();

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting('{');

pc.Advance();

pc.Expecting(); // expecting anything other than end of input

while ('}' != pc.Current && -1 != pc.Current) // loop until } or end

{

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

// _ParseJsonValue parses any scalar value, but we only want

// a string so we check here that there's a quote mark to

// ensure the field will be a string.

pc.Expecting('"');

var fn = _ParseJsonValue(pc);

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting(':');

pc.Advance();

// add the next value to the dictionary

result.Add(fn, _ParseJson(pc));

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting('}', ',');

// skip commas

if (',' == pc.Current) pc.Advance();

}

// make sure we're positioned on the end

pc.Expecting('}');

// ... and read past it

pc.Advance();

return result;

}

static IList<object> _ParseJsonArray(ParseContext pc)

{

// a JSON [] array - our arrays are lists

var result = new List<object>();

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting('[');

pc.Advance();

pc.Expecting(); // expect anything but end of input

// loop until end of array or input

while (-1!=pc.Current && ']'!=pc.Current)

{

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

// add the next item

result.Add(_ParseJson(pc));

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting(']', ',');

// skip the comma

if (',' == pc.Current) pc.Advance();

}

// ensure we're on the final position

pc.Expecting(']');

// .. and read past it

pc.Advance();

return result;

}

static string _ParseJsonValue(ParseContext pc) {

// parses a scalar JSON value, represented as a string

// strings are returned quotes and all, with escapes

// embedded

pc.TrySkipWhiteSpace();

pc.Expecting(); // expect anything but end of input

pc.ClearCapture();

if ('\"' == pc.Current)

{

pc.CaptureCurrent();

pc.Advance();

// reads until it finds a quote

// using \ as an escape character

// and consuming the final quote

// at the end

pc.TryReadUntil('\"', '\\', true);

// return what we read

return pc.GetCapture();

}

pc.TryReadUntil(false,',', '}', ']', ' ', '\t', '\r', '\n', '\v', '\f');

return pc.GetCapture();

}

While this is a bit fast and loose, it does demonstrate the concept of using ParseContext to implement a recursive descent parser.

Using this should significantly reduce the effort involved in doing so.