- Identify common Big O runtimes: constant, linear, quadratic and logarithmic

- Research the Big O runtime of built-in methods

In the last lesson, we defined Big O notation as a way to classify algorithms and give a summary of their time or space complexity based on the size of the inputs. We also learned how to calculate the Big O time complexity of an algorithm by counting the number of steps, and the space complexity by examining what memory is needed to store data.

In this lesson, we'll show a few other common Big O runtimes, and discuss how different types of inputs impact our ability to write more efficient code.

One of the algorithms we discussed in the previous lesson, findSock, looked

like this:

function findSock(laundry) {

for (const item of laundry) {

if (item === "sock") return item;

}

}We summarized the time complexity of our function like this:

Given an input array of n elements, the worst case scenario is that the

algorithm needs to make n iterations. In Big O notation, we can express this

as O(n), which is also known as linear time.

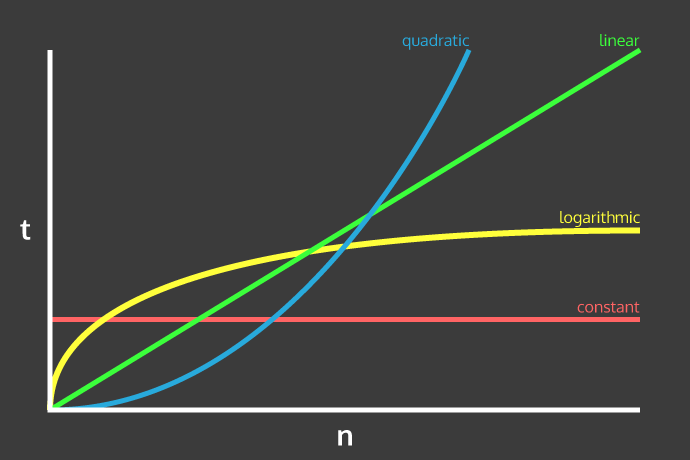

If you were to chart this on a graph, where the x-axis represents the number of

elements and the y-axis represents the units of work that your computer has to

do, our findSock algorithm's time complexity would follow the green line on

the graph below:

These are four of the most common Big O formulas, along with examples:

| Big O | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

| O(1) | Constant | Accessing a value in an object by its key |

| O(log n) | Logarithmic | Binary search (more on this soon!) |

| O(n) | Linear | Iterating through every element in an array |

| O(n²) | Quadratic | Nested iteration |

On this graph, the steeper the line is, the worse the algorithm's performance

is. We've already seen a couple examples of linear runtimes (our findSock and

average algorithms both have O(n) runtime) so let's take a look at some

examples of algorithms that have logarithmic, constant, and quadratic runtimes.

Let's revisit our sock finding example and see if we can devise a faster algorithm for finding the sock in our laundry. In our first example, the sock was in an unsorted pile of laundry, so our only hope of finding it was to go through each item in the laundry pile piece by piece.

What if our laundry were laid out on the floor in alphabetical order? Well, having our laundry sorted would give us a better way to approach this problem!

Consider a representation of our laundry as a sorted array:

["belt", "blouse", "pants", "shirt", "shorts", "sock", "underwear"];If we know that our laundry pile is sorted alphabetically, we don't need to start searching from the beginning. We could make a more efficient search algorithm by starting in the middle instead:

check the item in the middle of the pile

if the item is after our sock in the alphabet

check the first half of the pile

otherwise, if the item is before our sock in the alphabet

check the second half of the pile

otherwise, if that item is our sock

put the sock onThis strategy is like opening a dictionary (or a phone book) to try and find a particular word. If you open to a page that's after the word in the alphabet, you know your word is earlier in the dictionary, so you can quickly narrow down your search.

Here's a visualization of those steps:

["belt", "blouse", "pants", "shirt", "shorts", "sock", "underwear"];

// ^

// is this our sock?If that item isn't our sock, we can throw out the first set of items (since we know that "sock" comes later in the alphabet than "shirt"), and start in the middle again:

["shorts", "sock", "underwear"];

// ^

// is this our sock?Now we found our sock significantly faster, by cutting the size of our input in half each time we search! This is only possible because our input was sorted.

Even in the worst case scenario (our sock not being in the pile), we'd need at most 3 iterations to look through an array of 7 items:

["belt", "blouse", "dress", "pants", "shirt", "shorts", "underwear"];

// ^

["shirt", "shorts", "underwear"];

// ^

["underwear"];

// ^This approach benefits us more and more the larger our input size gets, since we can cut the area we're searching approximately in half on each iteration. What if we had 1000 items to look through? With a linear search, the worst case is that we'd need 1000 steps; with this new approach, we'd need just 10:

500 n / 2

250 n / 4

125 n / 8

72 n / 16

36 n / 32

18 n / 64

9 n / 128

4 n / 256

2 n / 512

1 n / 1024Here's how our algorithm for finding a sock would look in code:

function findSock(sortedLaundry) {

let start = 0;

let end = sortedLaundry.length;

while (start <= end) {

let mid = Math.floor((start + end) / 2);

if (sortedLaundry[mid] === "sock") return "sock";

if (sortedLaundry[mid] < "sock") {

start = mid + 1;

} else {

end = mid - 1;

}

}

}The algorithm we just came up with is an implementation of a binary search algorithm — it's a great algorithm to keep in mind for quickly finding elements in a sorted array!

We can summarize the time complexity of our function like this:

Given an input array of n elements, the worst case scenario is that the

algorithm needs to make log n iterations.

In Big O notation, we can express this as O(log n), which is also known as

logarithmic time.

While all this notation might look intimidating, you truly do not need to know

much about math to understand this. What's important to know is that

logarithmic time is more efficient than linear time. In math terms,

logarithmic time is really log base 2, and that 2 comes from the "cut in half;

cut in half; cut in half" part of the procedure.

As you saw in the previous example, the way the input data is stored plays a

big part in determining how efficient we can make our algorithm. For finding

an element in an unsorted list, the best we can do is O(n); with a sorted

list, we can be more efficient and achieve O(log n) runtime.

Let's take this idea of storing our laundry to another extreme. What if instead of having our laundry in an unsorted pile, or laid out in alphabetical order, we had an elaborate dresser, where each item of clothing had its own labeled drawer? Well, then finding our sock would be very easy! Our algorithm would look like this:

open the sock drawer in the dresser

if the sock drawer isn't empty

put on the sockThink about it for a moment: what kind of data structure have you encountered in JavaScript that serves a similar purpose, and allows us to access data just by knowing how that data is labeled?

That's right: an object! Looking up a key on an object is a very fast operation — we can consider it a constant time, or O(1), operation. So if our laundry data is stored in an object instead of an array, here's what our algorithm could look like:

function findSock(laundry) {

if (laundry.sock) {

return "sock";

}

}

findSock({

shirt: true,

shorts: true,

sock: true,

pants: true,

});We can summarize the time complexity of our function like this:

Given an input object of n key-value pairs, the worst case scenario is that

the algorithm takes 1 step to find the correct element.

In Big O notation, we can express this as O(1), which is also known as

constant time. No matter how large the input is, we can always find the

element with just one step!

The last runtime we'll discuss is quadratic time, or O(n²). To demonstrate

this, we'll need to modify our algorithm problem slightly. Instead of finding

just one sock, what if we needed to write an algorithm to find a pair of

matching socks? Let's assume again that we're dealing with an unsorted pile of

laundry. Here's how our algorithm might look:

take one item from the pile

compare it to the other items in the pile

if they match

put on the pair of socksAs you can see, we'll need to look through our laundry pile multiple times in order to find the matching pair of socks! We'll need to compare each item from the pile with all the other items in order to find the match:

["sock 5", "sock 2", "sock 1", "sock 3", "sock 1"];

// first sock: sock 5

// does it match sock 2? nope

// does it match sock 1? nope

// does it match sock 3? nope

// does it match sock 1? nope

// second sock: sock 2

// does it match sock 1? nope

// does it match sock 3? nope

// does it match sock 1? nope

// third sock: sock 1

// does it match sock 3? nope

// does it match sock 1? yep! we're doneSince we have to compare every sock in the pile against all the remaining socks, in terms of designing this algorithm, we'll essentially need to write a nested loop. Here's how we could approach this problem with code:

function findPair(laundry) {

// look through each item in the pile

for (let i = 0; i < laundry.length; i++) {

// look through the rest of the pile

for (let j = i + 1; j < laundry.length; j++) {

// check if it matches the first sock

if (laundry[i] === laundry[j]) {

return [laundry[i], laundry[j]];

}

}

}

}

findPair(["sock 5", "sock 2", "sock 1", "sock 3", "sock 1"]);For every n elements in the input array, we need to check it against the

remaining n elements. So as our input grows, our algorithm's runtime gets

worse by a power of two (n * n, or n²). We can summarize the time complexity

of our function like this:

Given an input array of n elements, the worst case scenario is that the

algorithm needs to make n² iterations.

In Big O notation, we can express this as O(n²), which is also known as

quadratic time. In some cases, this is the best runtime you can hope for,

but in general it's best to try optimize solutions where you have an O(n²)

runtime.

One major factor to consider when determining the runtime complexity of an algorithm is how well a language's built-in methods perform. For example, we stated earlier that "looking up a key on an object is a O(1) operation" in our discussion of constant time. But why is that the case?

When we make assertions like this, we're summarizing some of the lower-level work that JavaScript is doing under the hood when it comes to certain common operations, like looking up a key on an object. In reality, it's more complicated. Here is a general summary of common runtimes for operations involving objects:

| Method | Big O |

|---|---|

| Access (looking for a value with a known key) | O(1) |

| Search (looking for a value without a known key) | O(n) |

| Insertion (adding a value at a known key) | O(1) |

| Deletion (removing a value at a known key) | O(1) |

Arrays are another common data structure that you're quite familiar with at this point. Just like with objects, arrays have certain runtime costs for common operations, which we can summarize as follows:

| Method | Big O |

|---|---|

| Access | O(1) |

Search (.indexOf()) |

O(n) |

Insertion: End (.push()) |

O(1) |

Insertion: Beginning (.unshift()) |

O(n) |

Deletion: End (.pop()) |

O(1) |

Deletion: Beginning (.shift()) |

O(n) |

Creation from existing array (.slice()) |

O(n) |

For a more in-depth look at how we derived these runtimes, check out our Underneath Arrays lesson to learn more (you'll also see this lesson later on in the Canvas Data Structures and Algorithms course).

Further complicating matters for us is that the actual under-the-hood implementation of each of these methods depends on what JavaScript engine (Chrome V8, FireFox's SpiderMonkey, etc) our algorithm is running on. JavaScript itself is based on the ECMAScript specification, and each engine can interpret the spec in different ways, so to really be sure what a method is doing under the hood, you'd have to do quite a lot of digging!

Note: For the brave and the curious, one helpful resource when it comes to investigating JavaScript's built-in methods is the ECMAScript specification itself, which describes a general set of steps that every single JavaScript method should adhere to, regardless of what engine the method is implemented in.

For example, check out the specs for

.push()and.unshift(). Which of these methods looks like it involves more steps? Why might adding an element to the beginning of an array have a worse runtime than adding to the end?If you're ever curious how a JavaScript method works under the hood, the spec is a good resource (fair warning: it's certainly not light reading). Helpfully, the MDN docs include links to the ECMAScript spec at the bottom of each page.

We've covered a lot of material in the last couple lessons, so let's recap once more:

- Big O notation is used to classify algorithms according to how their runtime or space requirements grow as the input size grows.

- To calculate the time complexity of an algorithm using Big O notation, count

the number of steps the computer will take to run our code and then remove any

constants (so

O(2n + 1)becomes justO(n)). - To calculate the space complexity of an algorithm using Big O notation, check what variables are needed to store data in memory, and also remove any constants.

- Some common Big O functions with examples are:

- Constant time:

O(1)(looking up a value in an object) - Logarithmic time:

O(log n)(binary search) - Linear time:

O(n)(looping through an array) - Quadratic time:

O(n²)(nested loops)

- Constant time:

- You should be aware of the runtime cost associated with common methods on objects and arrays, such as access, insertion, and deletion.

Make sure to take a break before continuing onward - there's a lot of information to digest here! In the next few lessons, we'll practice writing more algorithms and talk through how to calculate their time complexity using Big O.