This is a reproduction study of:

The emergence of grid cells: intelligent design or just adaptation?

Emilio Kropff and Alessandro Treves, 2008

Written by David McDougall

Kropff & Treves [1] describe a method of producing grid cells. It appears to be supported by biology [2]. The gist of it is to make a spatial pooler [8] with two new mechanisms: stability and fatigue. The spatial pooler's overlap is stabilized by putting it through a low pass filter, which smooths over input fluctuations and removes spurious input fluctuations. Each cell also has a fatigue which slowly follows its activity, catches up to it and turns it off. The fatigue is equal to the overlap passed through a low pass filter.

- The effect of the stability mechanism is to cause the cells (or SP mini-columns) to learn large, contiguous areas of the input. As the sensory organ moves around the world, the stability mechanism causes the cells to represent large & contiguous areas of the world by forcing cells to react slower than their sensory input is changing.

- The fatigue mechanism shapes the contiguous areas of the grid cell receptive fields into spheres which are then packed into the environment. As the sensory organ passes through areas of the world, grid cells get tired and fall behind in the competition for a short while.

Grid cells are implemented as an extension to Nupic [4] as a subclass of the SpatialPooler (SP) class. The SP is modified in three ways:

- Stability and fatigue dynamics are applied to the overlap.

- The overlap is divided by the number of connected synapses to each grid cell.

- Synapses only learn when either the presynaptic or postsynaptic side changes its activity state. This filters out duplicate updates on sequential time steps. This is causes the grid cells to only learn when the agent is moving around, a stationary agents grid cells will not learn.

$ ./grid_cell_demo.py [--train_time number_of_steps]

Compare these results to Kropff & Treves, 2008, Figure 1.

The model is trained in a 200x200 arena by randomly walking. The simulated agent moves at a constant speed of 1.4 units per step. When it reaches one of the arenas boundaries it is turned to face back into the arena. The model is trained for 1 million steps, which took 64 minutes.

Figure 1: Example of random walk. This figure contains only 10,000 steps, as at 1,000,000 steps the path fills the image to solid black.

Figure 1: Example of random walk. This figure contains only 10,000 steps, as at 1,000,000 steps the path fills the image to solid black.

Each location in the arena is represented by 75 place cells. There are 2,500 place cells in total, for a sparsity of 3%. Nupic's coordinate encoder models these input cells.

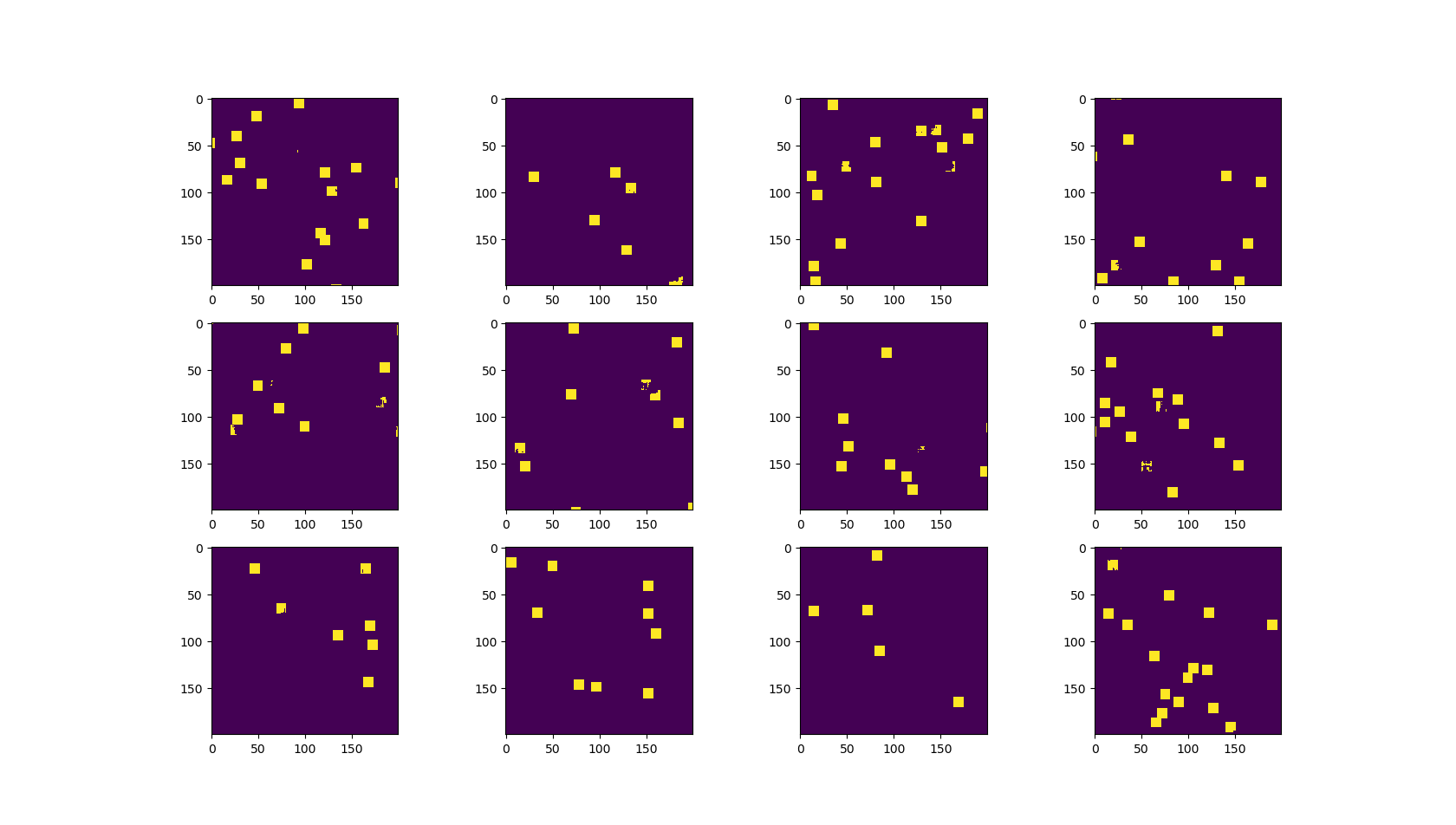

Figure 2: Example place cell receptive fields. Each plot is for a randomly selected place cell. The place cell activates when the agent moves into the yellow areas of the arena.

Figure 2: Example place cell receptive fields. Each plot is for a randomly selected place cell. The place cell activates when the agent moves into the yellow areas of the arena.

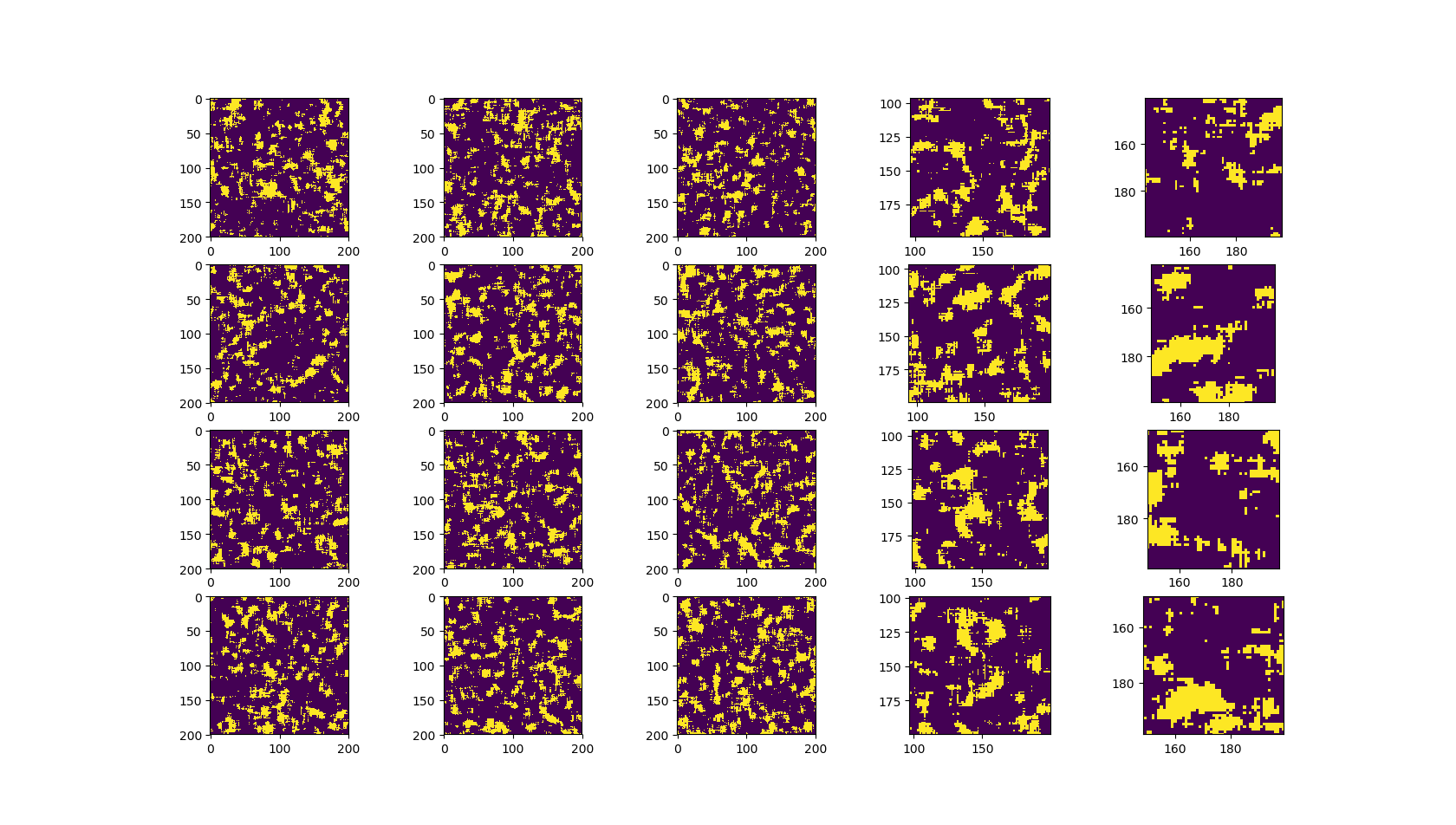

The model is tested by examining which locations each grid cell activates at (AKA its receptive field). The model is reset before measuring each location which removes the effects of movement, stability, and fatigue. Learning is disabled while testing. Figure 3 shows the results of this test performed on an untrained model. Figure 4 shows the results of this test performed on a trained model. Figure 5 shows the autocorrelations of figure 4, which should reveil any periodic components in their receptive fields.

Figure 3: Untrained grid cell receptive fields. Each box is a randomly selected grid cell. Notice that some of these figures are zoomed in.

Notice that the grid cells do not respond to large contiguous areas of the arena. There are many isolated (non-contiguous) activations. The small contiguous area are randomly shaped and have fuzzy, ill-defined borders.

Figure 3: Untrained grid cell receptive fields. Each box is a randomly selected grid cell. Notice that some of these figures are zoomed in.

Notice that the grid cells do not respond to large contiguous areas of the arena. There are many isolated (non-contiguous) activations. The small contiguous area are randomly shaped and have fuzzy, ill-defined borders.

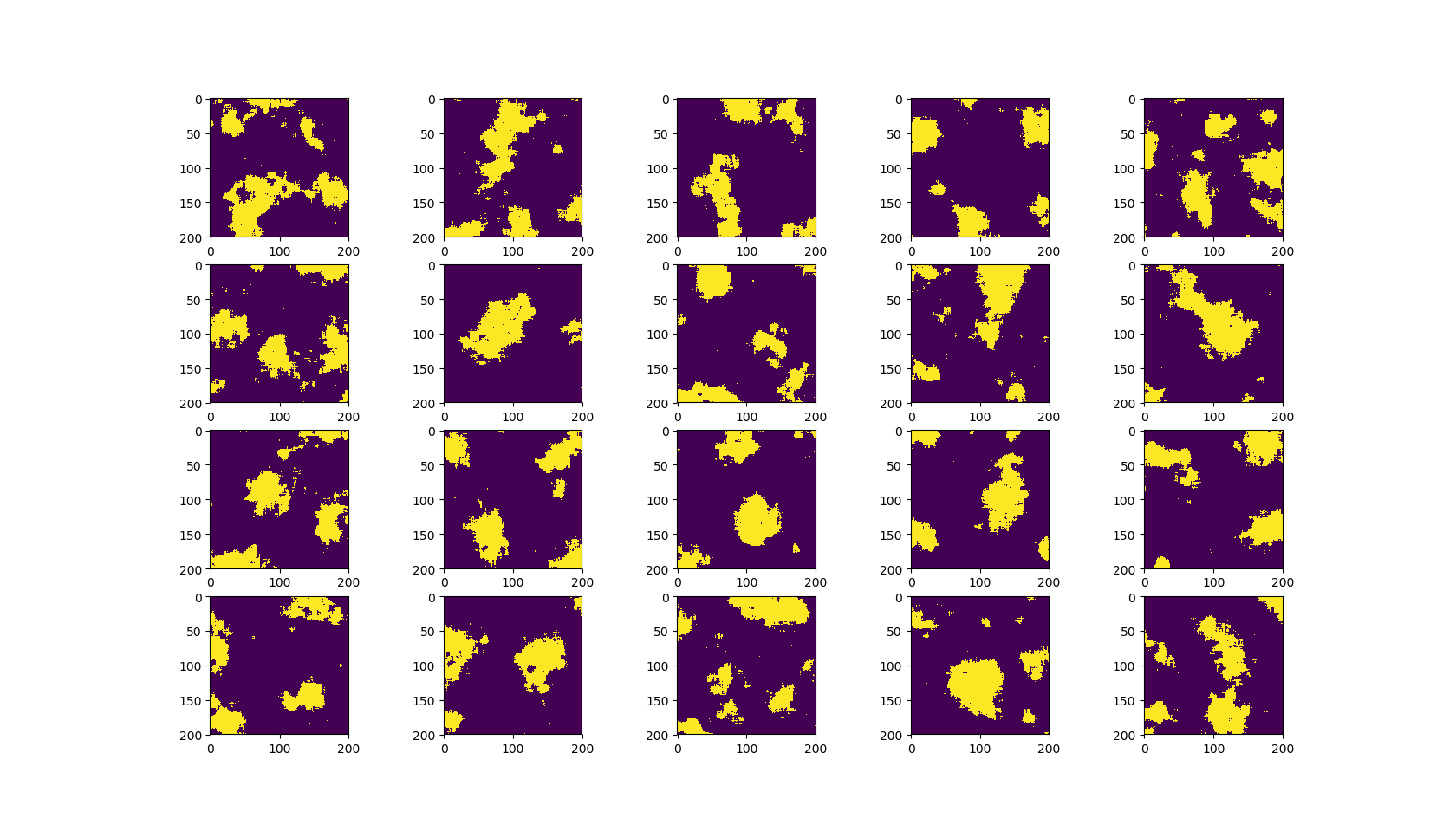

Figure 4: Trained grid cell receptive fields, randomly sampled. Notice that the grid cells respond to large contiguous areas. Many of the receptive fields are approximately round, the same size, and have sharp, well defined borders.

Figure 4: Trained grid cell receptive fields, randomly sampled. Notice that the grid cells respond to large contiguous areas. Many of the receptive fields are approximately round, the same size, and have sharp, well defined borders.

Figure 5: Autocorrelations for the grid cells shown in figure 4.

Several of these figures show a clear hexagonal pattern. Others show stripes, a pattern which (Kropff and Treves, 2008) predicts as a theoretical sub-optimal solution. Ideally, the surrounding periodic maxima would be as strong as the central maxima but this has not happened.

Figure 5: Autocorrelations for the grid cells shown in figure 4.

Several of these figures show a clear hexagonal pattern. Others show stripes, a pattern which (Kropff and Treves, 2008) predicts as a theoretical sub-optimal solution. Ideally, the surrounding periodic maxima would be as strong as the central maxima but this has not happened.

Increasing the training time and doing parameter optimization would be the next steps for this model. There is a standard metric for a cells 'gridness' [1][3] which makes possible methods of automated parameter searching such as swarming and evolutionary searches. It consists of the autocorrelation of the grid cells receptive field and some image processing to look for the grid pattern.

Hypothetical recurrent connections between grid cells could help align [5][6] and tessellate the grid. Collateral connections from many sources of input could aide in grid cell function, such as head direction cells and actions.

Before I do any of that though, I have a different experiment which I intend to perform. I will attempt to use the stability mechanism to induce view-point invariance in the L2/3 spatial pooler [7].

[1] The emergence of grid cells: intelligent design or just adaptation? Emilio Kropff and Alessandro Treves, 2018. DOI 10.1002/hipo.20520

[2] Tuning of Synaptic Integration in the Medial Entorhinal Cortex to the Organization of Grid Cell Firing Fields, Garden, Dodson, O’Donnell, White, Nolan, 2008. DOI 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.044

[3] Sargolini F, Fyhn M, Hafting T, McNaughton BL, Witter MP, et al. 2006b. Conjunctive representation of position, direction and velocity in entorhinal cortex. Science 312:754-58

[4] Matthew Taylor, Scott Purdy, breznak, Chetan Surpur, Austin Marshall, David Ragazzi, ... zuhaagha. (2018, June 1). numenta/nupic: 1.0.5 (Version 1.0.5). Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1257382

[5] Grid alignment in entorhinal cortex, Bailu Si, Emilio Kropff, Alessandro Treves, 2012

[6] Self-organized grid modules, Urdapilleta, Si, Treves, 2017. DOI: 10.1002/hipo.22765

[7] A Theory of How Columns in the Neocortex Enable Learning the Structure of the World, Hawkins Jeff, Ahmad Subutai, Cui Yuwei, 2017. DOI: 10.3389/fncir.2017.00081

[8] Cui Y, Ahmad S and Hawkins J (2017), The HTM Spatial Pooler—A Neocortical Algorithm for Online Sparse Distributed Coding. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 11:111. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2017.00111