Resolution proposal for the first project of the Logic Programming course unit @ FEUP, a game board called Three Dragons, based on the works of Scott Allen Czysz. Official Board and Rules.

- Three Dragons

- Three Dragons 2 made with ❤ by

In order to play the game, execute the following steps:

- On Windows:

- SICStus console

- Open the SICStus console and click on File->Consult;

- Choose the three_dragons.pl file from the source code folder;

- SICStus executable

- Add the executable to the environment variable path;

- Open a terminal window and execute

sicstus; - Execute

consult([path to the source code]/three_dragons.pl)..

- SICStus console

- On Linux:

- Open a terminal window and execute the following command sisctus-4.6.0.;

- Write

consult([path to the source code]/three_dragons.pl).;

- Run

play.to play the game.

AKA game description

Three dragons is a board game heavily inspired by ancient games such as Petteia, Tablut and Hnefatafi with some interesting additions:

- Pieces have strength and can capture pieces with lower strength

- There are "dragon caves", which can summon "dragons", more on that below

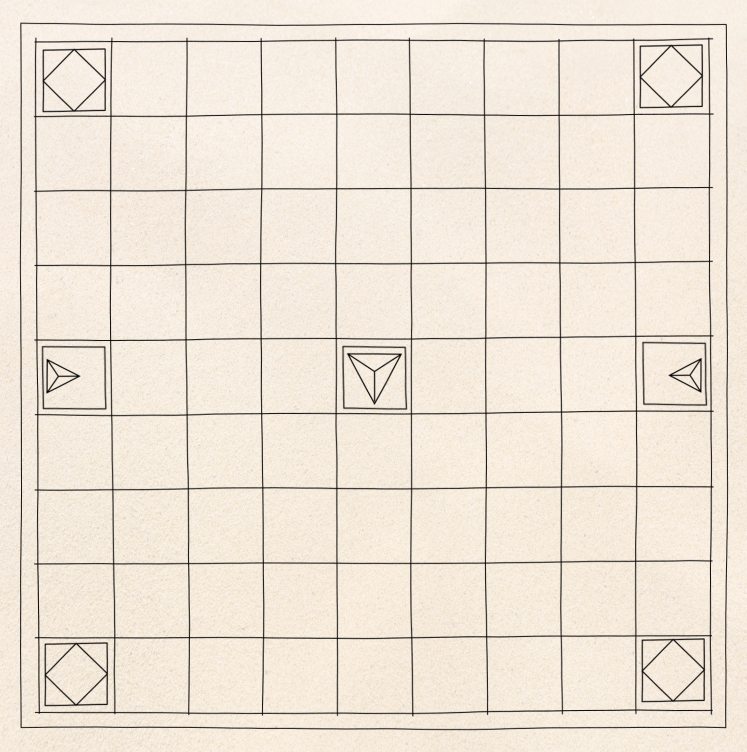

The game is named by the three triangular symbols across the center of the board representing dragon caves. In the four corners there are "mountains" that cannot be occupied by player pieces nor moved across. The same precedent is applied to the dragon caves.

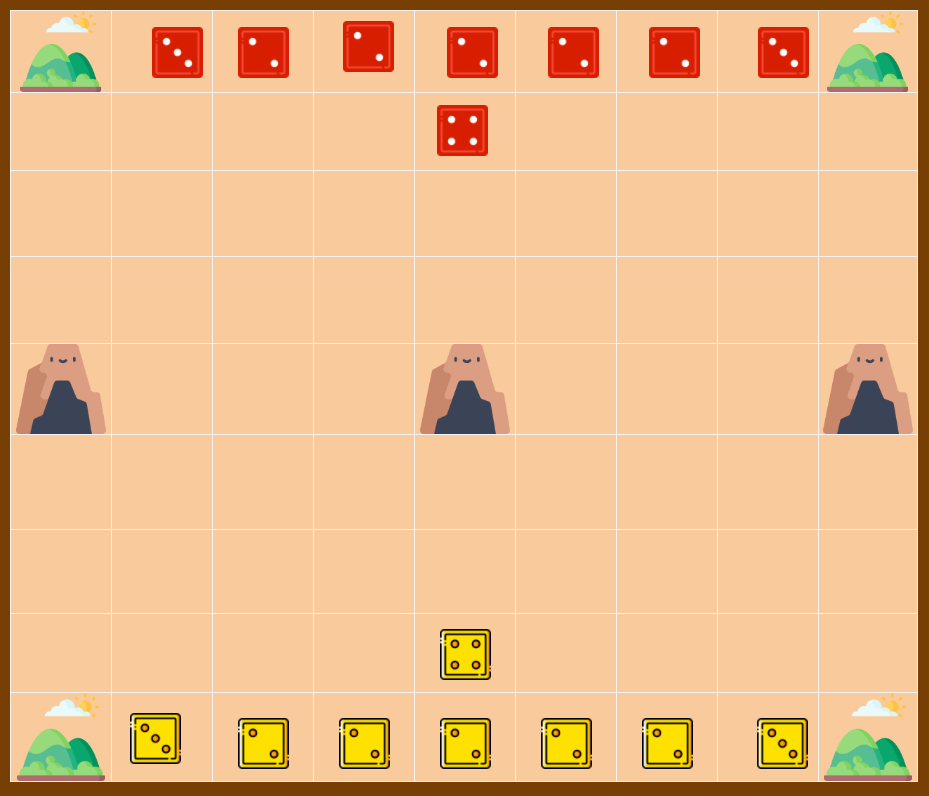

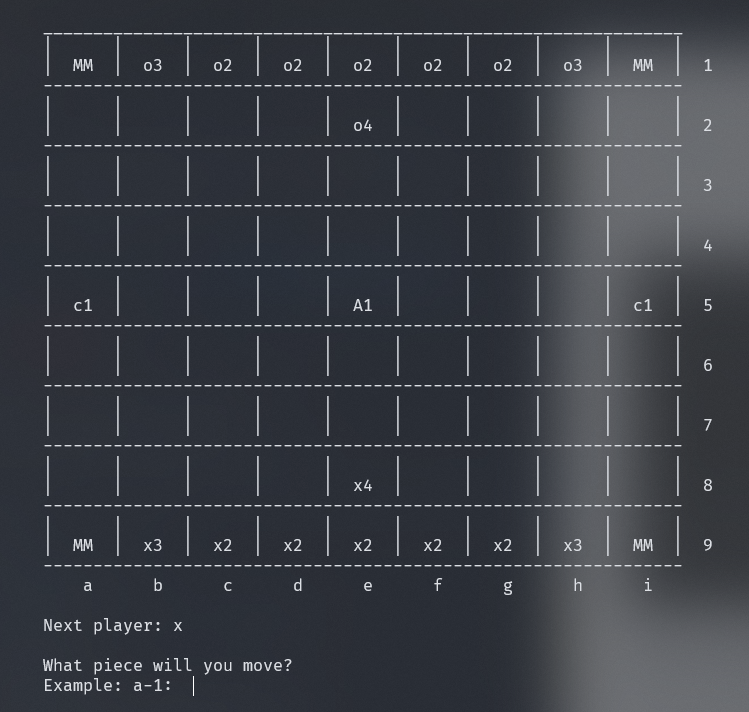

The initial disposition of the board, according to the official rules is as so:

Each player starts with 8 pieces, 5 with strength 2, 2 with strength 3 and 1 with strength 4.

Pieces move like a rook in chess, orthogonally, and any number of squares.

Pieces can be captured in two ways:

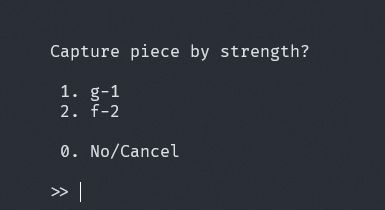

- by strength: a piece (1) with higher strength can capture another (2) with lower strength. The piece (1) will after loose a level of strength;

- by custodial: a piece is surrounded on both sides either by 2 enemy pieces or an enemy piece and an obstacle (dragon cave or mountain).

When a capture is made, the losing piece should be removed from the game.

The game ends when one of the players only has one piece left, hence the other player is declared the winner.

Dragons are regular pieces that can only be spawned whenever its cave is surrounded by all orthogonal sides. Only one dragon can be spawned from each cave. The side caves spawn a dragon with strength 3, while the main cave spawns a strength 5 dragon.

In its essence, the game state is no more than an array that contains the state information. The array is stored as follows [Board, Player, PlayerPieces, OpponentPieces, CaveL, CaveM, CaveR], where

- Board is a matrix that stores the board;

- Player is the current player;

- PlayerPieces is the number of pieces of the current player;

- OpponentPieces is the number of pieces of the opponent of the current player;

- CaveL, CaveM, and CaveR are designations of the three current caves, storing the number of dragons that can enter the game independently.

For ease of use, helper rules were implemented, where one can either get from or update a game state, such as:

% [...]

% gets the game state's board and current player to the Board and Player variables respectively

game_state(GameState, [board-Board, current_player-Player]),

% [...]

% updates the GameState1's current_player, player_pieces and opponent_pieces into NewGameState

set_game_state(GameState1, [current_player-NextPlayer, player_pieces-PlayerPieces, opponent_pieces-OpponentPieces], NewGameState).

% (the code above can be seen in the play. rule)The game board is represented through a matrix or, in Prolog, a list of lists.

| ?- init_board(X).

X = [['MM',o3,o2,o2,o2,o2,o2,o3,'MM'],[' ',' ',' ',' ',o4,' ',' ',' ',' '],[' ',' ',' ',' ',' ',' ',' ',' '|...],[' ',' ',' ',' ',' ',' ',' '|...],[cc,' ',' ',' ','AA',' '|...],[' ',' ',' ',' ',' '|...],[' ',' ',' ',' '|...],[' ',' ',' '|...],['MM',x3|...]] ?The current player is stored in a single atom, and exchanged between plays.

% global atom recognition

player1(x).

player2(o).

% the next player based on the last one

next_player(x, o).

next_player(o, x).The game board's width and height can be updated (defaulting at 9), future proofing the game in case new variants appear:

board_width(9).

board_height(9).In order to build a dynamic initial game state, one has to take in consideration the current dimensions of the board itself. Consequently, the building of the board is not simple. Its most high level rule can be seen below:

init_board(Board) :-

% initializes the top half of the board

second_player(Second),

init_board_half(Second, Half1),

% initializes the middle row

init_middle_row(MiddleRow),

append(Half1, [MiddleRow], Board1),

% initializes the bottom half

first_player(First),

init_board_half(First, Half2Reversed),

reverse(Half2Reversed, Half2),

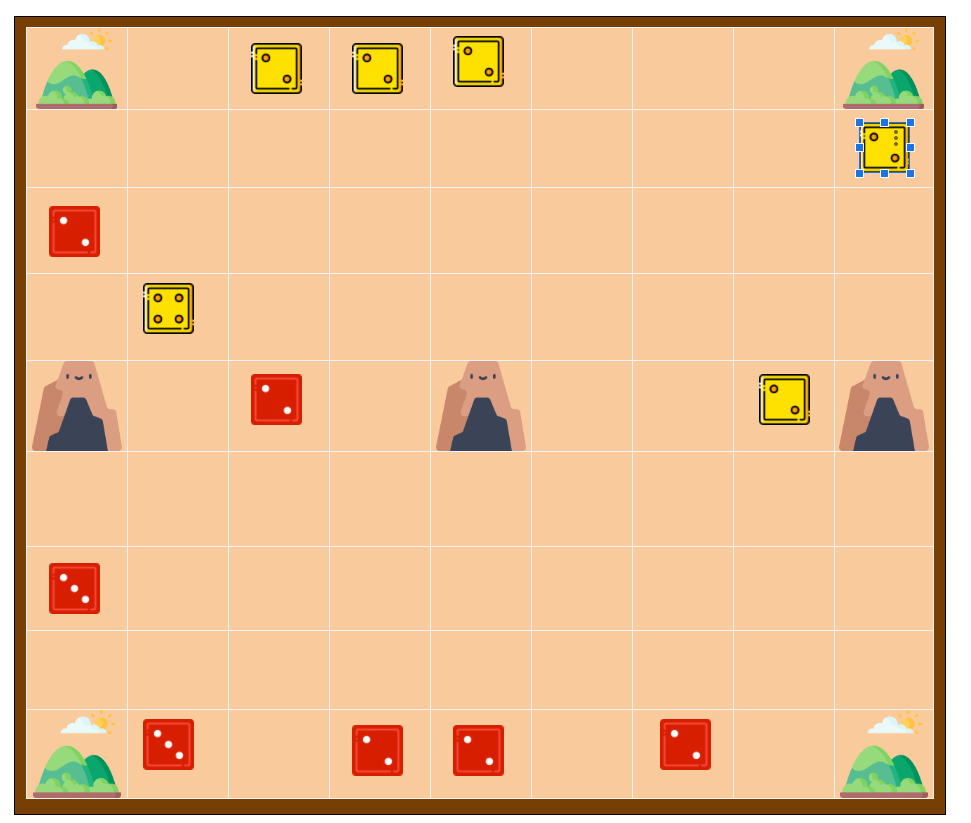

append(Board1, Half2, Board).As stated in the assignment, the intermediate and end game board examples are expected to be hard coded, instead of calculated. (For the sake of fidelity, all the present examples were taken from a real game of Three Dragons played amongst the members of this group).

These operations are performed as such:

show_intermediate_state :-

write_header,

inter1_state(GameState),

first_player(Player),

display_game(GameState).

inter1_state(GameState) :-

empty_board(Tmp),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp, 1, 3, Tmp1),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp1, 1, 4, Tmp2),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp2, 1, 5, Tmp3),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp3, 2, 9, Tmp4),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp4, 3, 1, Tmp5),

insert_matrix(o4, Tmp5, 4, 2, Tmp6),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp6, 5, 3, Tmp7),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp7, 5, 8, Tmp8),

insert_matrix(x3, Tmp8, 7, 1, Tmp9),

insert_matrix(x3, Tmp9, 9, 2, Tmp10),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp10, 9, 3, Tmp11),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp11, 9, 5, Tmp12),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp12, 9, 7, GameState).For this operation to be possible, it was required to implement a rule that would create a board with no more than the static elements, this is, without the playable pieces. This rule's called empty_board/1 in the example given and runs in the exact same way as the init_board/1 example stated above, but writing an empty cell in all the correspondent playable pieces.

It was also required to implement a way to insert elements in a list of lists in a friendly approachable way, such rule is stated below (if you want to have a more clear grasp on what's happening, you can take a look at the actual code where it is formally documented: here):

insert(Element, [_|T], 1, [Element|T]).

insert(Element, [H1|T1], Position, [H1|T2]) :-

Position1 is Position - 1,

insert(Element, T1, Position1, T2).

insert_matrix(Element, [MH|TH], 1, Column, [Res|TH]) :-

insert(Element, MH, Column, Res).

insert_matrix(Element, [HT|MT], Row, Column, [HT|Res]) :-

Row > 1,

Row1 is Row - 1,

insert_matrix(Element, MT, Row1, Column, Res).The intermediate state example given above produces (and was taken from) this exact game board state:

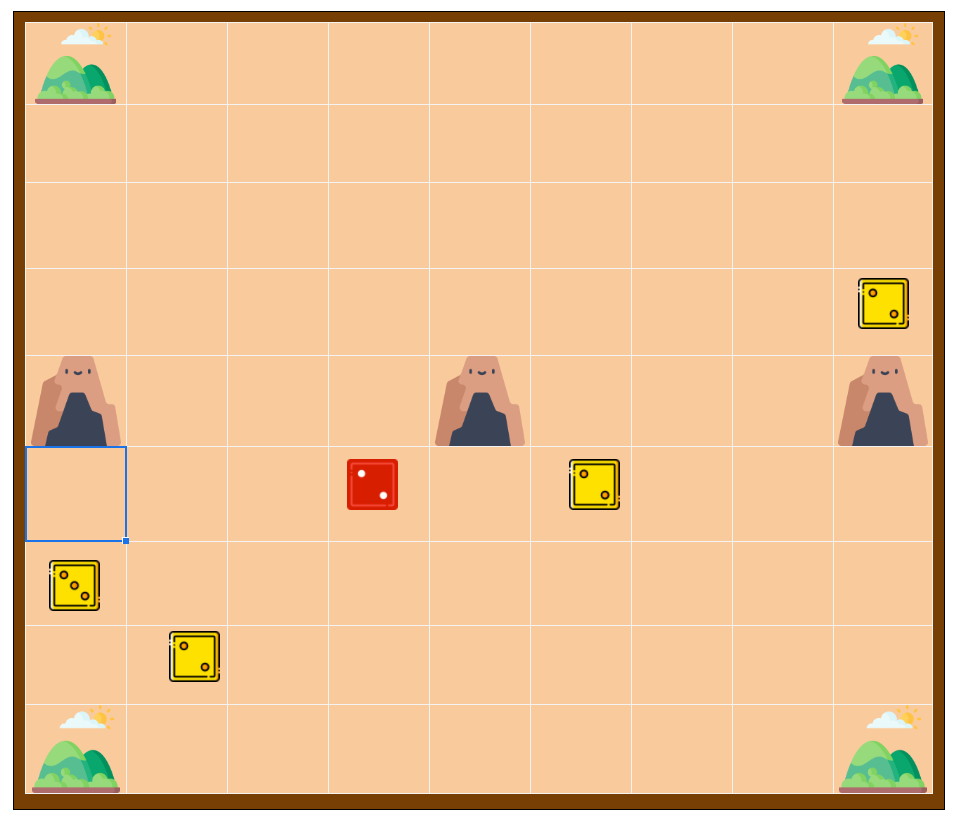

The operations around the final game board example are exactly the same as the one in the intermediate example.

show_final_state :-

write_header,

final1_state(GameState),

write_end_board(GameState, o).

final1_state(GameState) :-

empty_board(Tmp),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp, 4, 9, Tmp1),

insert_matrix(x2, Tmp1, 6, 4, Tmp2),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp2, 6, 6, Tmp3),

insert_matrix(o3, Tmp3, 7, 1, Tmp4),

insert_matrix(o2, Tmp4, 8, 2, GameState).Resulting in:

Note: remember that the game ends when one of the players has only one piece

More details on the looks are given below (Visualization of the Game State), and, internally, the pieces' implementation the most complex of the implementations:

color_value(o1, o, 1).

color_value(o2, o, 2).

color_value(o3, o, 3).

color_value(o4, o, 4).

color_value(o5, o, 5).

color_value(x1, x, 1).

color_value(x2, x, 2).

color_value(x3, x, 3).

color_value(x4, x, 4).

color_value(x5, x, 5).These color_value facts work both ways, upon a piece, o1 for example, one can easily find its owner and value, being them o and 1 respectively in this example. If one owns a piece owner and its value, color_value can returns its internal representation as well.

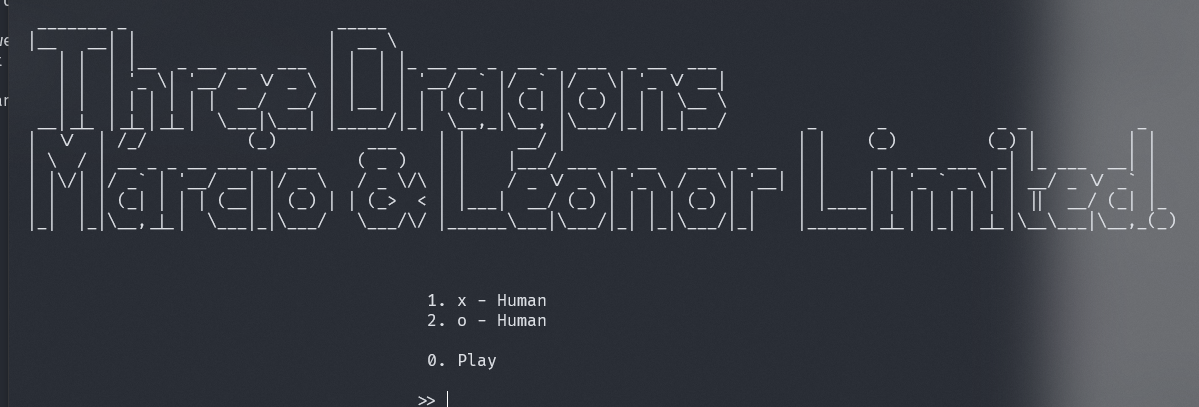

The main menu is simply able to update the type of player and start the game. For that, under src/io/menu.pl there is a set of rules that ease menu handling that, given the length limits, won't be explored in this README.

Example of menus being used below:

The menus accepts index and value input. For example, in this last example, input 1. and g-1. would result in the same.

The visualization of the game state predicate is implemented as follows:

write_board(Board, NextPlayer) :-

write_border,

write_pieces(Board),

write_next_player(NextPlayer).Starts by writing the top border of the board (merely underscores), draws the board itself, and ends by giving an indication about the next player. When a game ends, it displays the winner instead of the next player.

The drawing of the board also follows a very intuitive and textbook implementation:

write_pieces([], 0) :- nl.

write_pieces([H|T], Rows) :-

write('|'), write_array(H), nl,

write_line,

Rows1 is Rows - 1,

write_pieces(T, Rows1).Writing the pieces of a single row separated by some margin and a |. For now, the pieces' representation follows a simple idea: displaying its owner and level, such that x2 is the representation of a piece owned by the player x and with level 2. The static board elements are:

- Mx for the mountain

- cx for the small caves

- Ax for the large cave

where x is the number of dragons left in the given cave.

As is implemented in the code snippet below:

empty(' ').

mountain('MM').

possible_move_representation('<>').

caves_row(5).

left_cave_col(1).

middle_cave_col(5).

right_cave_col(9).

cave('c1', 1, 1).

cave('c0', 0, 1).

cave('A1', 1, 5).

cave('A0', 0, 5).

cave('c1', 1, 9).

cave('c0', 0, 9).The caves hold, in the second argument, the number of possible spawns left.

A line, which is no more than a bunch of hyphens (calculated accordingly to the board width), is displayed dividing the rows.

Below lies the current representation of the initial state of the board:

The valid_moves/3 predicate is implemented as below:

valid_moves(GameState, Player, ListOfMoves) :-

game_state(GameState, board, Board),

all_valid_moves(Board, Player, 1-1, ListOfMoves).This predicate uses the game_state/3 to fetch the current board and calls the all_valid_moves/4:

all_valid_moves(_, _, Row-_, []) :-

board_height(Height),

Row > Height.

all_valid_moves(Board, Player, Row-Col, ListOfMoves) :-

Col1 is Col + 1,

board_width(Width),

Col1 =< Width, !,

possible_moves(Board, Player, Row-Col, List1),

all_valid_moves(Board, Player, Row-Col1, List2),

append(List1, List2, ListOfMoves).

all_valid_moves(Board, Player, Row-Col, ListOfMoves) :-

Row1 is Row + 1,

possible_moves(Board, Player, Row-Col, List1),

all_valid_moves(Board, Player, Row1-0, List2),

append(List1, List2, ListOfMoves).This predicate calculates the cells a piece can go from a specific cell. It checks if the cells are inside the board and if they are empty with the possible_moves/4. It also appends the lists with the results in a final list, ListOfMoves.

The move/3 predicate is implemented as below:

move(GameState, Row1-Col1-Row2-Col2, NewGameState) :-

game_state(GameState, [board-Board, current_player-Player, player_pieces-PlayerPieces, opponent_pieces-OpponentPieces, caves-Caves]),

get_matrix(Board, Row1, Col1, Piece),

insert_matrix(Piece, Board, Row2, Col2, Board1),

clear_piece(Board1, Row1-Col1, Board2),

check_if_captures(Board2, Row2-Col2, Player, OpponentPieces, Board3, NewOpponentPieces),

summon_dragon(Board3, Row2-Col2, Player, PlayerPieces, Caves, Board4, NewPlayerPieces, NewCaveL-NewCaveM-NewCaveR),

reset_caves(Board4, Row1-Col1, Caves, NewBoard),

set_game_state(GameState, [opponent_pieces-NewOpponentPieces, player_pieces-NewPlayerPieces, cave_l-NewCaveL, cave_m-NewCaveM, cave_r-NewCaveR, board-NewBoard], NewGameState).It first uses the game_state/2 predicate to fetch the board, the current player the player pieces, the opponent pieces and the caves.

After that, it fetches Piece, the piece that is going to move and inserts it in the new cell in Board1. It removes the piece in the old cell in Board2.

In check_if_captures/6 predicate, it checks if there's a possibility to capture an enemy piece and if so, it asks the human user if it wants to. The new board is returned in Board 3 such as the new number of enemy pieces in NewOpponentPieces.

In summon_dragon/8, it checks if a new dragon is summoned and if so, the new board is returned in Board4, such as the new player pieces in NewPlayerPieces and the caves in NewCaveL-NewCaveM-NewCaveR.

In reset_caves/4, if necessary it resets a cave that was turned into a dragon. The last update of the board is returned in NewBoard.

Finally, the move predicate updates the new information with the set_game_state/3 predicate.

The game is over when a player only has one piece. In order to check if the game is over, the game_over/2 predicate is called and it's implemented as below:

game_over(GameState, Player) :-

game_state(GameState, [current_player-Player, opponent_pieces-1]).This predicate uses the game_state/2 predicate to check if there's only one opponent piece and if so, it returns the Player as winner.

The value/3 predicate is implemented as below:

value(GameState, Player, Value) :-

game_state(GameState, [current_player-Player, player_pieces-PlayerPieces, opponent_pieces-OpponentPieces]), !,

Value is PlayerPieces - OpponentPieces.

value(GameState, _, Value) :-

game_state(GameState, [player_pieces-PlayerPieces, opponent_pieces-OpponentPieces]), !,

Value is OpponentPieces - PlayerPieces.This predicate evaluates the state of the game. The goal for a player is to have more pieces than the opponent and the bigger the difference the better. Therefore, Value is the difference between the number of the player's pieces.

The predicate choose_move/4 is implemented as shown below:

choose_move(GameState, Player, Level, Move) :-

minimax(GameState, Player, Player, Level, _, Move).The minimax has 2 base cases and a recursive step, the code won't be shown here because of visibility purposes, but can be found in src/game/bot.pl.

Essentially, for level 0, the bot will choose a random move and play it. For level 1, it gets the best possible immediate play. The recursive will iterate through levels, calculating level number of plays ahead until it reaches level 1.

For more information on minimax, click here.

After the development of the project, we conclude that prolog as a programming language is not ideal to develop applications based on I/O operations. However, using logic operations is very intuitive.

Our minimax algorithm is not optimized for big levels of depth because there's always a lot of options to calculate.

Also, because we're using the built-in predicate "read", if the user only writes ., the program crashes. It also applies if the user writes for example a-. when choosing a board cell.

All the code in this repository is commented with the assistance of PlDoc.

More info on Prolog documentation with PlDoc right here.