How to Build a Social Network

Intro

Hi! This is a little microproject I want to do: I want to compress my years of experience building the API backend of a top-50 Steam game into a bunch of weird, rambling advice that I can deliver with all of the authority of someone who can't differentiate success due to merit from success due to luck.

You

If you don't know the basics of programming, nothing that we cover here is going to make any sense to you. I'm hoping to target an audience of at least junior-level developers who understand how to code but maybe want some advice on the bigger picture story of how to construct an application.

That's what we're here to talk about!

Fast

We are going to be going through this very quickly.

This is out of necessity - the last time I tried to put something like this together I------ got stuck on character encoding and Unicode for like 8 entire pages. ( The proof is here, peruse at your own risk.)

Character encoding is really neat, and someday I hope to turn those pages into a totally separate presentation, but there's no way we're going to make it through everything if I don't trim some details so that we can make it through this in less than 100,000 years.

Based on the word count and my average elocution speed, I'm estimating that just working through the whole essay is going to take me about two and half hours. And I speak.. relatively quickly.

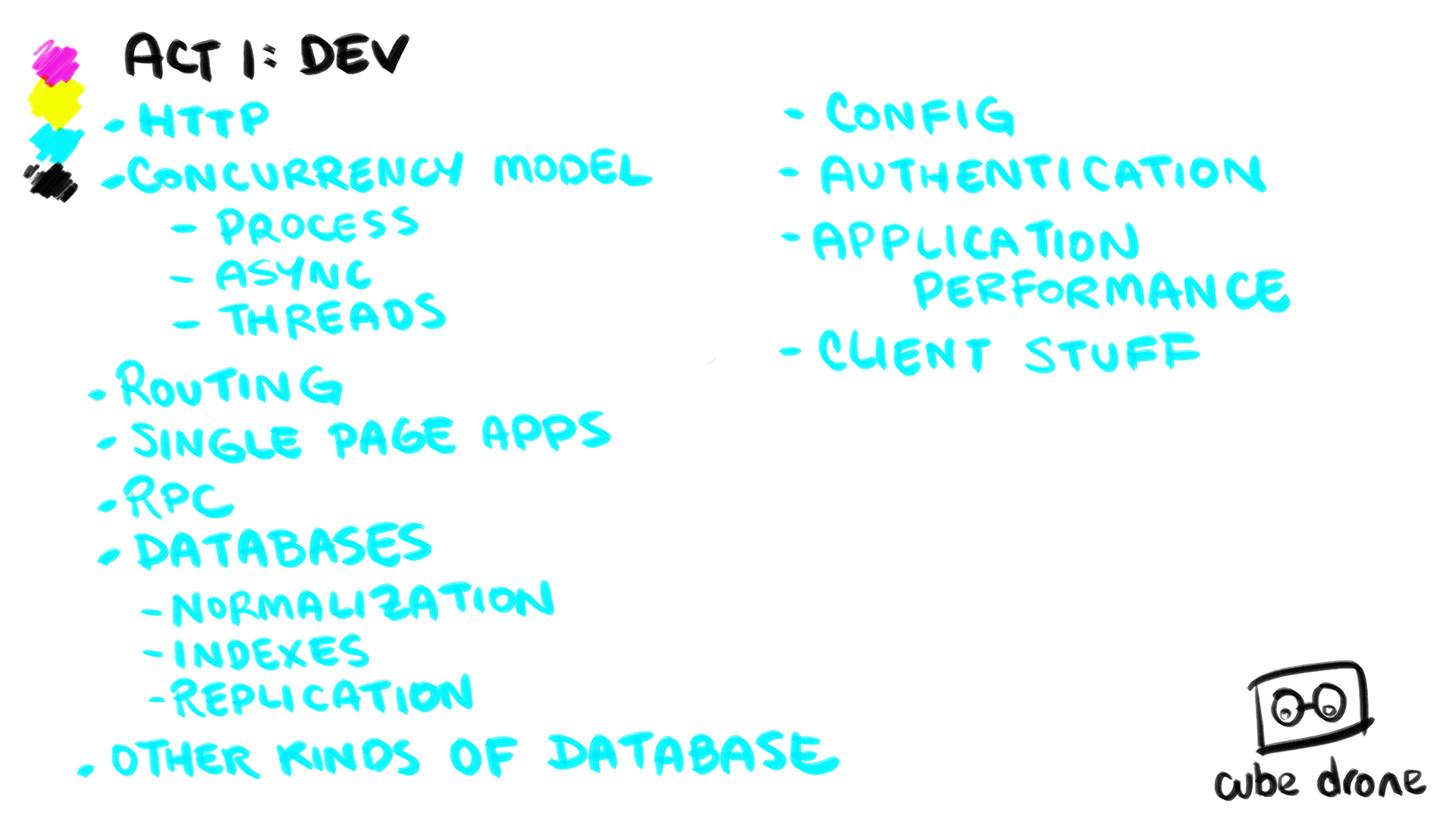

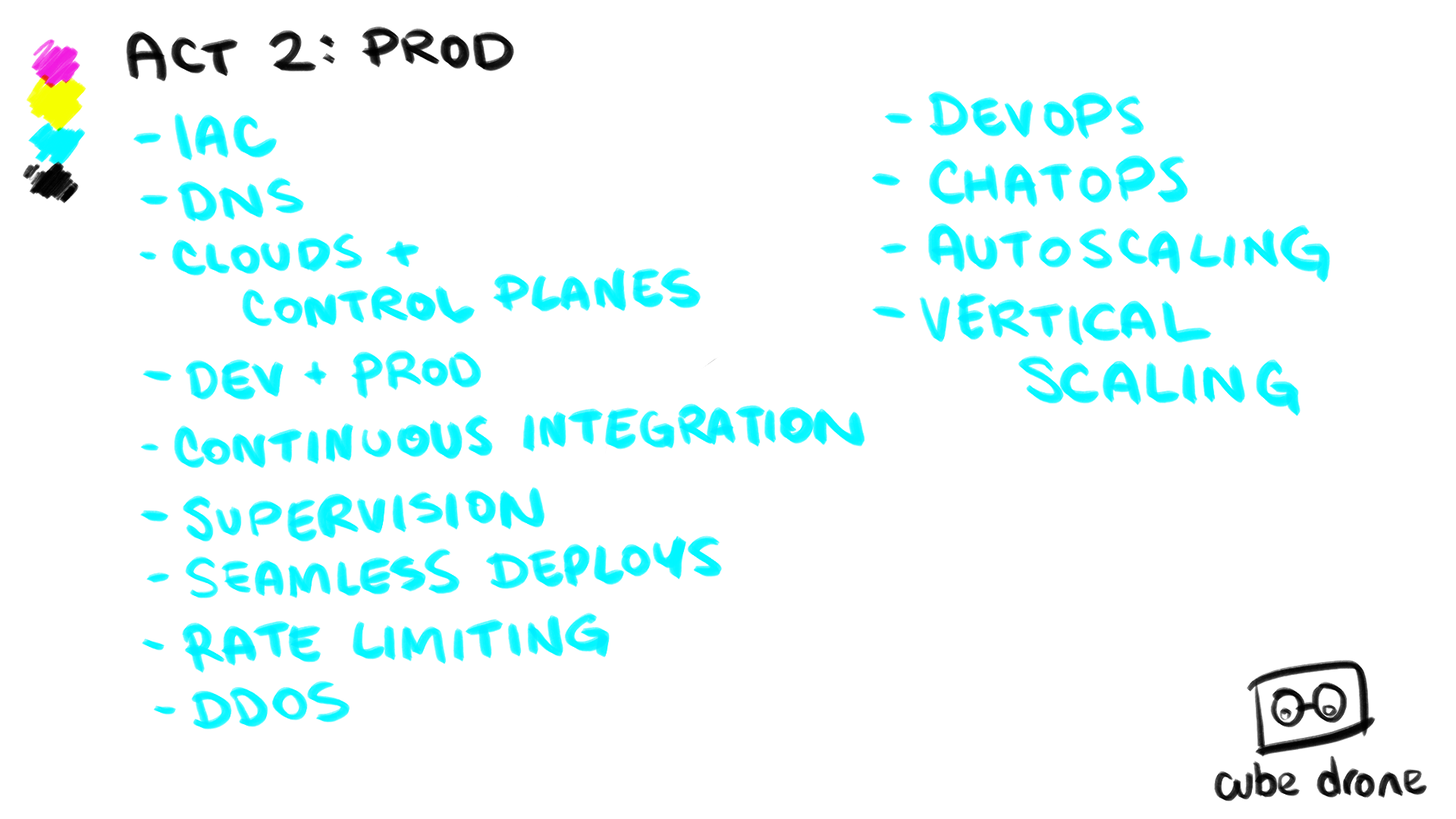

Here, I'm going to pop up the Table of Contents so you have an idea what we're going to cover.

We are going to go fast.

Act I: Dev

Client & Server: The Absolute Most Basic of Basics

The first thing to talk about is what a web application looks like.

- You have a browser.

- You type in cube-drone.com/hats.

- The browser automatically adds

http://to the front of that - It uses DNS, the Domain Name System, to resolve

cube-drone.comto an IP address. - It uses HTTP, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol to connect to port 80 on the IP address it got for

cube-drone.comrequestingGET /hats. - The server responds: with a 300 redirection, telling it that actually it should go look at

https://cube-drone.com/hats, because we use encryption in this house young man. - The browser tries again, with that new url.

- Tiiiiiiiiihis time trying port

443, the port for encrypted HTTP traffic. - There's some web application server code on the other end of that connection. It gets the request for

GET /hatsand responds with a 200 OK and a page of HTML. - The browser gets that page of HTML and renders it in glorious beautiful HTML style.

- Inside that HTML is a whole mess of JavaScript.

- That JavaScript executes code to take over the browser window, building and constructing a whole little application inside the browser.

- That in-browser application does a bunch of interesting stuff, up to and including sending remote procedure calls back to the

https://cube-drone.comserver to perform commands and ask for more information. - That's a web application!

So building web applications is largely about programming the parts that are happening on the server over here.

HTTP

HTTP, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol, is all just a bunch of fancy stuff that sits on top of regular ol' TCP/IP.

What's In a URL

put a diagram here, dummy

- Protocol (http, or https - this doesn't have to be http - a url can identify a resource that you connect to with all sorts of different protocols - redis, or postgres, or gopher, or... whatever)

- Hostname (and port, if necessary)

- Path & Query

This divides pretty nicely into "the server we plan to connect to", "the language we intend to speak to it", and "the thing we want that server to get for us"

GET & POST and some more esoteric codes

There are two primary kinds of message you'll send to the server - GETs and POSTs. When you GET a path, you're saying to the server- whatever is there, go get it for me. When you POST to a path, you're saying - here, server, I have something, take it and put it at the path I gave you.

For example, imagine a theoretical comments section - you might GET /blog/1234/comments , which the server would respond to with all of the comments for a specific blog entry - and then you might send a POST to /blogpost/1234/comments containing some structured data that it would then add as a comment.

GET and POST are the important ones - GETs are for getting data, POSTS are for changing data, and that's all you really need to know. There are some more esoteric ones, like DELETE, and PUT, and HEAD, and PATCH, but you mostly don't need to use them. We will talk a little bit more about those later.

Headers

Your GET or POST request don't travel alone - they can also bring a bunch of metadata with them. This metadata comes in key/value pairs called "Headers".

Here are some of the HTTP headers that are included with a request to a website.

Here are some of the Headers that are sent back from the server in our HTTP response.

Cookies

Cookies are also a kind of header - they're a bit of extra data that you can include with a request to a website.

The server can also, when it responds to you, ask you to hold on to a little bit of extra data along with your request, with an expiry date - so, for example, when I hit cube-drone.com, it might respond, saying

"hey, for the next week, every time you send me a request, could you also send me this fourteen digit number?"

That turns out to be wildly useful for authentication, which we'll talk more about soon!

Status Codes

Every HTTP response comes with not just text, but also a three digit number indicating how well the request went.

200 is the number that means "everything went okay". Numbers in the 300 range mean "your data is somewhere else", Numbers in the 400 range mean "you screwed up somehow", and numbers in the 500 range mean that the server that you've connected to has managed to light itself on fire somehow.

So, for example, 301 - that's "moved permanently" - whatever you expected to find at this path, it actually lives somewhere else, and the response will tell you where to look. Your browser will helpfully follow this trail automatically.

That also means, you can set a 301 pointing to another 301, pointing back to the original 301, in hopes that your user's browser will follow that chain forever, trapping your end user in a hell from which there is no escape - but most unfortunately, most modern browsers won't fall for that and will stop following redirects after a while and simply give up.

404 - that's "not found" - it means you screwed up, because you asked for something that just isn't there.

500, that's an "internal server error" - most servers are configured to spit out a 500 if something inside them breaks unexpectedly. It's almost always a sign that not only has something gone wrong, it's someone else's fault. Some programmer, somewhere.

Other Kinds of Software We Won't Be Talking About

So, this talk, is about client-server web applications, in specific.

Here are some things we won't be talking about:

Single User Applications or Video Games

These are just... programs that you give to people. There's no client, there's no server, you give them a program and they run it.

P2P

More and more of the internet is running off of peer-to-peer protocols - bittorrent, Tor, IPFS, Dat, and the very stupid world of blockchain are all capable of running entirely without a server - applications built using these protocols are incredibly powerful and increasing in popularity - but the model for developing them is significantly more complicated than the one for traditional client-server architectures.

Play by Mail

It's possible to run the entire client/server communications network over mail, or - if you prefer- carrier pigeon. If you use a carrier pigeon to send me some mail with a HTTP request on it, I could easily respond with some more mail containing a HTTP response - however, this system is almost untenably slow and poop-laden, so we're going to leave it out for the sake of time.

Serverless

This one is worth a little bit more thought. So - various cloud products - Amazon, Google, Azure - they'll offer you whole programming interfaces abstracting away just about everything about web programming. Essentially - they'll write almost everything for you, and you just provide the application logic. Then, you give them the code and they run it in the cloud, they handle the scaling, and they charge you micropennies every time someone hits one of your endpoints.

If you connect this to one of their databases that also scales up automatically for you, your whole application can just exist "on demand", and for prices that are at least competitive with what you'd pay to host your application on a traditional server infrastructure.

I'm not going to go into detail on my thoughts on serverless - it's pretty cool - but what we are going to talk about here are all of the components and practices that Amazon or Google would be replacing for you. If you do end up embracing serverless, it'll help you to know most of this stuff, at least at a high level, anyways.

OS (Linux, Dummy)

So if we're not running our software on the gigantic mega-structure that is someone else's server, what are we running it on?

Well, Linux. Something like 900% of all of the servers in the world are running some variety of Linux. It's free, it's powerful, it's stable, it's lightweight.

The Command Line

When I started with web programming in the mid oughts', I had just come off of a lot of Windows-driven application and even video game development and I was surprised - because a lot of Windows development is really heavily graphical user interface driven.

I came in expecting tools like Visual Studio to handle all of the work of building web applications, with lots of buttons and toggles and bits - but no. Web application development is deeply, fundamentally tied to our old friend, the command line.

I thought this was some real regressive DOS-grade bullshit. But I learned. There a lot of reasons that the command line is the programmer's computer interface of choice - not so clumsy or random as graphical user interface, an elegant weapon, for a more civilized age.

- Writing command line programs is way easier than writing GUI programs

- Composing command line programs together is way easier than sharing data between GUI programs

- Learning command line programs, especially when you're used to them, is lightning quick

Language

One of the the first questions that you'll probably come to when building a web application - any application, really - is "what language should I use"?

If you're learning everything from the ground up? The answer is probably Python or Javascript.

Concurrency Model

The reason that your choice of language matters so much is because different languages have very different models when it comes to managing concurrency.

When it comes to web applications, concurrency is non-optional. Imagine if, for example, a web server could only deal with one person at a time. It would be slow.

Handling concurrency is also really complicated - enough so that the concurrency model you choose effects every decision you make afterwards. It's a big deal.

Remember, You're Not Writing A Database

There's a common misconception when it comes to programming languages - the best one is the one that's fastest, right?

Well, not necessarily.

It's possible to write web applications in pretty much whatever language you like. The speed of your web application server isn't going to be your first scaling hurdle - and even PHP will cheerfully run a website for your first 10,000 users, no problem.

Static languages, dynamic languages, they're both fine. Some people like type systems, some people don't, I've definitely seen some pretty compelling evidence that they don't affect your productivity too much either way.

I'm pretty sure that most languages have fairly sane package management at this point - a good package manager where you can save a list of dependencies and automatically install it after pulling the repository - and most popular languages have libraries for just about everything you'll need.

In fact, what you should probably be doing, is writing applications in whatever language you're most comfortable writing code in - fast code is utterly worthless if you don't have any users, and the best way to get some users is with something - anything - that works.

The actual wrong decision here is choosing a language that's more complicated than you need for the task at hand, and wasting a bunch of time struggling with it.

Process Concurrency

"But languages like python, ruby, or PHP don't support concurrency"

Now, for those of you in the know, you know I'm sort-of lying about that - each of those languages has support for async and threads if you go spelunking in them - but let's pretend for just a moment you build a standard flask or django application in Python - that application can really, truly, only process one request at a time. It gets a request, and it has to respond to that request before it can move on to the next one. I've already said that this would be slow - but Python and PHP have been used to power some of the biggest websites on the internet. How do they do that?

Well, your operating system has concurrency built in. When you're launching a Python program in production, you're actually launching dozens of processes, each containing an identical Python program with its own fully independent memory. Then, an external program - an http server - load balances requests to all of these internal processes. In many cases this external program will also manage the whole process lifecycle for these internal processes. This external program is almost always written by people who are very smart about writing high performance code, so you're leaning on them to do a lot of the heavy lifting for you. All of the actual concurrency is provided by your operating system's scheduler - which, thanks to the fact that the processes don't share anything, means that you barely have to think about concurrency at all.

This process-based concurrency model is the simplest, the easiest to deal with. From the point of view of the program you're writing, there is no concurrency. You just have to respond to one request at a time.

If you are just learning, I strongly, strongly recommend a language that scales with a process-based concurrency model, like Python or Ruby. They are not the absolute fastest, but, remember: You're Not Writing a Database.

Async (Co-Operative Multitasking)

However, process-based concurrency is heavy. Each process demands its own space in memory. Ideally, you're writing your server programs to use very little memory on their own, but it is still a concern.

On top of that, a lot of time in web programming is spent waiting on network resources. One of your processes might send a query to a database, and then just wait ... for hundreds of milliseconds. In computer time, that's an eternity. Your operating system's scheduler will check in on that process every now and then, but most of the time it's just going to be waiting for the database to get back to it.

What would be ideal, is, instead of jumping around from waiting process to waiting process, if we could find a way to get a single process to just be busy all the time. That means any time it has to wait on anything, it just remembers that it's waiting for that thing, and goes to do something else for a while.

This is asynchronous programming - a style of programming where you have to intentionally indicate within the code "oop, this bit might take a while, don't come back to this until the thing is done".

Programming like this is hard. You have to relearn a lot of your habits to switch from thinking synchronously to thinking asynchronously - writing your software around the idea that it has to consciously give up control any time it's waiting on something to execute.

This also isn't really concurrency - it all still happens on a single thread of execution - but - this technique allows you to write a single process that stays white hot. Each individual process is able to deal with hundreds of simultaneous requests, because whenever it's waiting on something for request A, it can be working on something for request B, or C, or D, or E. If you have more than one CPU - if you want TRUE concurrency - you still have to scale out using the process model - one process per CPU - but only one process per CPU, because the process itself is handling the mechanics of keeping itself busy.

This is the scheme underlying node.js, or some of python's newer frameworks.

No Shared Memory

The process-based concurrency model is very powerful and flexible - but - if you think about it - it really limits the amount of memory available to each of your processes. Lets say you have a computer with four CPUS, and 16GB of RAM - if you're process scaling with Ruby, and you create 16 processes to jump between, each process only has access to 1 gigabyte of working memory. If you're process scaling with node, and so you only need to create four processes - one per CPU - each process only has 4GB of memory to work with.

Now, one of the reasons this is important is because a lot of process-scaled languages are also garbage collected and very flexible. Which means - memory leaks can accumulate pretty easily in the code. Which means your program can eat all of its working memory, and then die.

Also, and this is key: where do these programs keep everything? They can't keep stuff in working memory - if they do, only one of the many processes actually running on your computer would ever be able to see it. You send a request to log in on this process and then you send another request but you're not logged in on this process, nightmare.

So, for this reason - amongst others - these servers are written according to something called a "Shared Nothing Architecture" - nothing that they need lives exclusively in their own working memory - all they do is connect to external databases that actually store all of the real, important information. If you reboot one of these processes, it ... doesn't matter. Because they aren't storing anything important. This also is super important for the resilience of your systems - it doesn't matter if you reboot any of these servers, they'll just wake up and start handling requests again, as if nothing happened.

Threads and Shared Memory

Remember when I said "we're not writing a database?" That's just - good life advice. Don't write a database. It's really hard.

If we were writing a database, we'd want both full concurrency and access to all of the shared memory the system has to offer. That's when we start to get into the realm of truly concurrent programming models - which means - threads.

And where you have threads, you have synchronization issues. It's a fact of life - any time two CPUs have access to the same part of memory at the same time, you're only moments away from a whole raft of horrifying issues having to do with mutexes and semaphores and race conditions.

Go, Java, Scala, C#, Elixir, Erlang, Rust, C++, and C are all languages that let you go to town with threads and shared memory. Many of them ALSO have access to async coding primitives. You can mix and match.

One way to control that complexity of managing access to mutable shared memory is with immutable data structures and message passing. Immutable data is an enormously powerful technique for concurrent systems, because you don't have to manage access to it - it's always safe to read - the only thing that needs to be consistent is its lifecycle - that data has to be readable as long as there are still threads that might want to read it. A very common pattern for creating stable, manageable concurrent systems is by creating a bunch of little micro-systems that send immutable messages to one another - each thread almost feeling like a little processes within the application itself - this is based on a technique from Erlang, although commonly it is called the Actor model - and you'll find versions of it in many of these languages.

Another way to control the complexity of shared mutable state is with clever data structures. Using tools like atomic operations and copy-on-write, it's possible to build data structures that are highly resistant to being used in ways that will corrupt data.

Another way to control that complexity is just to... embrace the madness. Get deep into mutex town and hope to hell you don't make a mistake. This is a common tactic for C++ programmers, who are crazy, and Rust programmers, who have invented a compiler so complicated that if you can write programs for it, at all, they're probably safe to run.

Needless to say, unless you ARE writing a database, I don't necessarily recommend managing your own threaded concurrency and shared memory. In fact - if you're listening to me, an idiot, and learning things, you're probably not at the point in your career where you are ready to write database code yet.

Git

This deserves just one slide.

Your code... goes in git. On GitHub. If you're fussy and you want to use some other source control system, by all means - but, by default, your code goes in git. On GitHub.

Application Basics

So, now that you've chosen a language, it's time to decide on... a framework.

Framework

Every language has a bunch of different web frameworks, each of them encompassing a single philosophy on how to build a web server.

When I first started building web applications, I tended towards very minimal framewoks, like flask for python, because their simple operation required very little learning on my part, and I could just slam code together until something interesting happened.

Then I started to tend towards more more maximal frameworks like Codeigniter for PHP, Django for Python, or Ruby on Rails for... Ruby - because they were very complete and opinionated and I learned a lot from them about what components actually need to go into a full-fledged product.

And.. now.. I'm back to preferring very minimal frameworks because now I'm very opinionated about how I want my code to go together, and I'd rather build everything, myself, from the ground up.

So... I don't know - spend some time learning about the different philosophies behind some of the different frameworks, try some out, see what you like.

Routing and Request, Response

The one feature that I have never, ever seen a a web application framework leave out is routing. It feels like, almost, the minimum thing a web application framework needs to be .... is routing.

As we covered a little earlier, the role of a web server is to take HTTP requests and turn them into HTTP responses - and so, the beating heart of a lot of application code is a table that looks kinda like this:

* GET / => fn home()

* GET /register => fn register_page()

* POST /register => fn register()

* GET /login => fn login_page()

* POST /login => fn login()

Just... a mapping between URL paths and the functions that are responsible for responding to requests for that path.

How these functions operate can vary wildly from environment to environment, but ultimately they're responsible for taking a request and converting it into a response.

Uh, PHP is kind of a funny special case in this sense, because, at least the way I remember it, PHPs routing is automatic - you have PHP files in a file tree and the server automatically routes requests to the file matching the query - so, if you have GET /home/register.php then it's going to look in your PHP folder for /home/register.php and execute whatever it finds there.

As far as I know, PHP is the only "modern" language that does anything like this. It saves you the trouble of having to maintain a routing table, but at the cost of generating that routing table automatically in ways you may not approve of.

Local Environment Setup & Automation

Django and Rails won me over to this way of thinking, but I think it's great and it belongs everywhere: some frameworks provide a command line application with the framework that you use to run automations against your system.

So, you might type... django run and it'll boot up your django application, or django create potatoModel and it'll create an empty potato model for you.

I haven't written django in a really long time - probably almost a decade - but I'm still actively including little automation-focused command line applications with everything I write, because the convenience of being able to type jake run and have my application set up all of its dependencies and boot itself up is huge.

There is no space in my head for storing complicated setup arguments or scripts. If I run my little command line app, it'll tell me all of the things it can do, and then I don't have to remember anything.

The various make clones - make classic, rake, jake, and python's invoke - are all pretty good for this.

Classic Websites vs. Single-Page Applications

One of the earliest things you're going to need to decide about your application is whether it's going to operate as a classic web application or a Single-Page Application.

Website: Classic

The way that websites used to work, long ago, was that each individual page request would result in your getting a different HTML page. If you hit /subscribers/jeremy, the system would go find a subscriber named Jeremy in its database, build a HTML page for you, and return that HTML page. If you wanted to post a comment on /blog/comments, that page would have a HTML Form element on it, and that HTML Form element, after you filled it out, would trigger a HTTP POST request, followed by a full page load of whatever HTML came back from that POST request. In fact, every single interaction would involve a full page reload.

This way of doing things often felt a little sluggish - think Craigslist, or PHPBB - and it is a terrible choice for a website with a lot of interaction - buut - it's a really powerful technique for websites that don't have a lot of complex interactions. If all your application needs to do is pull database records and display them neatly, this is easily the best way to go.

The simple nature of websites that are just websites also plays particularly well with search engines, which find this kind of content the easiest to index.

Progressive Enhancement

Of course, you could take a classic website and include snippets of JavaScript functionality to liven things up, add basic application features, and build buttons and menus that perform more interactive functionality. If you do this, while still keeping the site largely working like a Classic Website, you're engaged in Progressive Enhancement - you've got a classic website with some UI features, but everything still works like a regular website. Old reddit worked this way, I personally liked it better than the new reddit.

Single-Page Applications

Nowadays the most popular way to build complicated websites is to skip the "website" part entirely: when you go to any url under modern reddit.com, for example, the site doesn't engage in routing the way that we described it earlier, at all. Instead, reddit routes everything to the same result: the entire JavaScript source code for a complete application.

This divides your web program into two programs: the Javascript client, which runs on your users' computer, in their browser, and your server, which provides the "Application Programming Interface", or API.

The client application boots up and starts running immediately, then, it uses its own internal routing rules to determine what to display to you based on the URL that it can see. If that requires information from the servers, (it will), it'll get that information by performing remote procedure calls against API urls on the reddit servers. These calls will still communicate using HTTP, but they won't send HTML - instead, they'll communicate using a object serialization protocol like JSON.

It Doesn't Have to be JSON But It's Always JSON

There are literally no rules about what language the JavaScript application you've loaded needs to use to communicate with the backend server. It could send binary data, or plaintext, or XML - but in practice, the "Javascript Object Notation" is the de-facto standard for all non-HTML web communication.

It became popular because it is just a subset of JavaScript, which means that JavaScript can parse it essentially for free - which means you don't have to send the user's computer a whole bunch of code for deserializing data.

Templating

Many web application frameworks include a templating system, which is a system for rendering arbitrary data into HTML.

You'll note that in the "Single Page Application" style of web development, there's not actually too much need to engage with templates on the server side - all your server will be doing is sending the user an application, and then communicating with that application back and forth using Remote Procedure Calls - so... any HTML befingerpoking is gonna be happening inside the JavaScript application, not from your server code.

Modern frameworks... don't bother themselves with templating nearly to the extent that older frameworks did.

Remote Procedure Calls (RPC)

On the other hand, modern frameworks do a LOT of remote procedure calls over HTTP.

There are potentially countless different ways to do RPC over HTTP - more schemes than you can shake a stick at - but practically the most popular method is REST.

Let's talk about a few schemes:

XML-RPC and SOAP

These were early standards for doing RPC calls over HTTP. They used a lot of XML rather than JSON, and tended to be very popular with Java programmers, which made them very unpopular with everyone else. We ... don't talk about them much anymore.

REST (FIOH)

REST stands for "Representational State Transfer", and if you spend any time looking into the philosophies of Representational State Transfer you will be overwhelmed with a sudden desire to throw yourself into traffic. The ideas of Representational State Transfer don't actually map to API design, at all, really. REST is a philosophy about how hypermedia should work, so, if you're designing a new HTML, you should read about REST - but you're not designing a new HTML, because we already have HTML. Which is doing fine.

The name REST is all wrong if you're using it to describe doing RPC over HTTP, it should have been called FIOH.

"Fuck it, Overload HTTP".

I've stolen this term from a very good blog post . (Which I've linked below)

The way that Fuck it, Overload HTTP works, is that you just map all of your HTTP paths to different things your system can do.

So, if you POST some JSON to /register with your email and password in it, it could create a user account. A POST to /login might log you in, and a GET from /employees/12834 might retrieve the employee data from employee #12834.

With a little bit of skill and thought you can map your entire application's programming model to HTTP calls against specific URLs. Lots of programs are written this way.

And remember those esoteric HTTP verbs from before, like DELETE and PUT and HEAD and PATCH? You can use those here, too, if you want. Or don't. It's totally up to you!

GraphQL

One thing you will quickly discover writing apps in the FIOH style is that writing expressive queries in HTTP urls is really hard - and, for security reasons, you're not allowed to just pass structured query language directly through your web server into your database.

So, some folks at Facebook built GraphQL, which is a whole query language that you can offer over HTTP, as part of your API. If a lot of your API is devoted to queries, GraphQL can probably replace a lot of it with a query language.

I don't really have a lot of thoughts about GraphQL. If you need to write an API that's capable of processing really complicated queries, maybe it's the right tool for you!

WebSockets

This is something that Single Page Applications can do that classic websites definitely can't: they can open a WebSocket against the backend server.

Unlike HTTP request/response, where every interaction with the server is going to involve a request and response, a WebSocket is a full bidirectional communication pathway between the client and server - the connection stays open, and either side of the transaction can send messages whenever they want.

This is most useful when programming real time systems - chat clients, for example. Building a chat client using request response would require that your client application regularly poll the server - do you have any new information for me yet? What about now? What about now? Using a websocket, the server can wait, and push messages to the client when it actually has something to send.

There are drawbacks to this, though - maintaining a WebSocket connection on the server side is much more heavyweight than just responding to simple http requests.

On top of that, remember our shared-nothing process scaling model? This significantly complicates that, because our websocket connection represents a permanent connection to a server. The socket needs to stay connected to the same process each time it connects to your backend, and that process needs to be able to simultaneously manage connections to hundreds of different clients.

This is really hard without services that can manage some concurrency - you know, these guys (node, elixir, rust, C++, etc). So, socket-heavy architectures tend towards more consolidation and more concurrency - larger servers, using threads and shared memory - which is why backends in Elixir or Rust are often popular for real-time systems.

WebRTC

Another way for Single Page Applications to communicate is with WebRTC - or Web Real-Time-Communication, a protocol that allows clients to communicate amongst themselves in a peer-2-peer fashion, useful for exchanging high speed audio and video data.

We're not talking about p2p today. Like I said before, that's out of the scope of this presentation.

Just Use FIOH

At least, for now, the dominant way to do things is REST - or, FIOH, if you'd prefer.

MVC

Okay, jumping back to our web framework - one of the things that many web frameworks provide is a recommended structure for your codebase.

Django and Rails, for example, are built around Model-View-Controller architectures, where your code is divided into

- Models, responsible for mapping database tables to application objects

- Views, responsible for mapping application objects to HTML using templates, and

- Controllers, which are the parts that actually handle the request/response, and tie Models and Views together to build the application's functionality

Pipelines and Middleware

Rust's warp and Node's express are built around more of a Pipeline model - a request is passed in and then the request and response are successively modified in stages until the response is ready to give back to the user.

A very common concept in web frameworks is the idea of "middleware" - once you build a pipeline stage that does something like "rate limiting" or "checking authentication", it's easy to roll it out across dozens of different endpoints.

Backing Services

And now we need to talk about some of the backing services you are almost certainly going to need to connect to, to turn your application into an application.

The Database

The beating heart of every modern web application is some kind of database.

It is the permanent store of information at the center of everything.

Database Authentication

Most commercial databases have a built-in authentication system. This authentication system is to authenticate access directly to the database itself - it's important not to confuse the database's authentication with your own application's authentication.

If people want to log in to your website, they'll be interacting with auth code that you wrote. Database Auth controls who is allowed to connect to the database and what they are allowed to do - so, pretty much, just your application, and you.

Some databases don't ship with any authentication at all - or, authentication is turned off by default. Everybody who can find the database on the network can do whatever they want with it. It's really important that - if you make a database accessible on a public network, you must authenticate access to it. Again, this feels so obvious that I'm embarrassed to say it, but, every year there are reports of hackers just cruising in to completely open systems with real production data on them.

Database Protocols

The way that you connect to your database is rarely simple HTTP requests. Instead, databases usually interact via some protocol of their own design - very often a binary protocol rather than a plaintext one.

Postgres, for example, communicates using the Postgres Wire Protocol. Mongo communicates using the Mongo Wire Protocol.

Communicating with these databases almost always involves finding someone's implementation of the database protocol for your language of choice. Very often, there are many competing implementations of the database libraries - you'll have to evaluate these and choose ones that work well for your purposes.

Remember when looking for database libraries, you're evaluating them based on

- How popular are they? Are lots of other people using these libraries?

- Are they maintained? When was the last time the library maintainers changed anything?

- Are they documented? Can you understand how to use the library?

- Do they use a programming model that makes sense in the language that you're working in?

- Do they support connection pooling? Reconnect logic?

- Do they have the official blessing of the database company, or are they officially published by the makers of the database?

Not Talking about SQL

The dominant way to interact with databases is using a Structured Query Language.

A full discussion of how modern SQL and NoSQL databases work is outside of the scope of this presentation. It's a big, big topic that deserves a whole presentation on its own.

Tl;dr: In your database, you have tables of data, and you'll issue queries that request and update rows against those tables. To learn more, read a database manual.

Normalization

(joke on slide: "All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection")

Okay, I need to talk about normalization a little.

Just to introduce the topic, let's imagine we have a table with some users in it:

| id | user | country | ip | type | perms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dave | USA | 203.22.44.55 | admin | write |

| 2 | chuck | CA | 112.132.10.10 | admin | write |

| 3 | biff | USA | 203.22.44.55 | regular | read |

This table has an id, uniquely identifying the user, a username, a country code, an IP address, a user type, and user permissions.

Maybe you're looking at this and thinking: hey, this table has some problems.

Like - if all admins have "write" permissions, and all regular users just have "read" permissions, why not separate out the admin stuff into its own table. We can just store the ID of the rows we're referencing.

| id | user | country | ip | type_id |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dave | USA | 203.22.44.55 | 1 |

| 2 | chuck | CA | 112.132.10.10 | 1 |

| 3 | biff | USA | 203.22.44.55 | 2 |

| id | type_name | perms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | admin | write |

| 2 | normal | read |

Look, we did a normalization! Now if we want to update our admin permissions, or change a type, or add a new type, we only have to make that write one place, instead of hundreds of times across our entire table.

And the only expense was that we made our read a little more complicated - now in order to get all of the information we used to have in one table, we need to JOIN the type_id against the new table we've just created. Now our queries are against two tables instead of just the one.

Awesome! But... we can go further. Let's normalize harder. We can split out the country, and the IP data, too.

| id | user | country_id | type_id |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dave | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | chuck | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | biff | 1 | 2 |

| id | type_name | perms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | admin | write |

| 2 | normal | read |

| id | country | full-country-name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | United States of America |

| 2 | CA | Canada |

| id | user_id | ip_id |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 |

| id | ip |

|---|---|

| 1 | 203.22.44.55 |

| 2 | 112.132.10.10 |

UNGH. Can you feel that. It's SO NORMALIZED. We've got a many-to-many relationship so that users can have lots of IP addresses, but those IP addresses live in their own table, just in case one of them changes.

We've also got our countries neatly organized into their own table, in case the country name changes.

We get all of this, and the only expense is that our queries get just a touch more complicated, because now they're querying not one but five different tables.

Denormalization

(joke on slide: except too many layers of indirection)

Uh, you might have noticed that that last example was a bit ridiculous.

It's possible that country codes don't need to be normalized into their own table.

In fact, country codes change very, very rarely, if at all - and - it turns out, doing a full-table find-and-replace once every 5-10 years might be less complicated than doing every single query for the entire lifetime of your application across two tables instead of just one.

That goes doubly for maintaining a whole extra table for IP address normalization, which I definitely just did as a joke.

The driving factor behind normalization comes from a good place, a place of good engineering that lives deep within your gut, but - it's really possible for the desire for properly normalized systems to lead us down paths that actually make our designs worse, and harder to maintain.

There's a lot of value in simplicity, honestly, the first table I showed you was probably the easiest of the lot to actually understand and work with.

When I worked at a major telecom over a decade ago, every single row in every single table was normalized - like in my second example, the joke example. It meant that no matter what sort of data you wanted to update, you were guaranteed that you'd only ever need to update it in one place at a time - or, more likely, you'd have to create a new row and write a reference to that new row. Individual SQL queries would often run 400, 500 lines, just to pull basic information out of the system.

Don't do that. It's bad.

Avoid Unnecesary Joins

Joins make reads slower, more complicated, and harder to distribute across machines.

Up until fairly recently, MongoDB just didn't allow joins at all. Google's first big cloud-scale database, BigTable, was so named because it just gave you one big table. No normalization, just table.

Normalization is still a enormously useful technique for how you design the layout of your data, but be aware: you probably need a lot less of it than you think.

Locks

Each row in your database can only be written to once at a time. Your database provides its own concurrency control around records, so that you don't accidentally corrupt them by writing them simultaneously.

However, one thing to be aware of is how and how much of your database locks with every write.

There are modes, for example, of

Indexes

"My queries are slow".

Again, database indexing is a huge, huge topic, more than I can cover here without going into just even significantly more detail.

But, I have a few things to say:

Running a Query from an Application Server on Production Without an Index: It's Never Okay

The only time it's really acceptable to run an unindexed query is when you're spelunking for data on your own, and even then, you're taking your life into your own hands. Letting an unindexed query into the hands of your users is a mistake - worst case scenario, malicious users will find that query and hit it again and again and again until your database server lights itself on fire and falls into the ocean.

Covered Queries are Great

If you only request information out of the database's index, the database doesn't have to read anything from disk. This is a huge optimization - take advantage of it when you can.

Indexes Live in RAM

This is a bit of a broad generalization, but indexes are huge data structures that live in RAM. Every new index on a large database table fills up RAM on the database you're writing to.

Most systems accumulate data a lot faster than they delete data - many systems don't delete data at all, or only do it if required by law - what that means is that the indexes will only ever get bigger, bigger and bigger and bigger, until eventually they don't fit on one computer any more.

Every Index Slows Down Writes

When you write something, anything to your database, a huge number of indexes need to be updated as well.

Now, it might seem like I'm being a bit contradictory here - you should have indexes for every query, you should pull as much information from indexes as you can, but also, your indexes slow down writes and grow unbounded until they fill your database server's RAM and blow up prod. But yes, all of those things are true at the same time.

Schema Evolutions/Migrations

If you're using a SQL-based database, you are going to be asked to define your table layout up-front. This is your database schema, describing the shape of data in your database, as well as the indexes that must be created.

Once your table is live, the only way to make changes to that table is to write schema-changing ALTER queries against the table.

Many languages and environments provide a system that allows you to define a starting schema for a table, and then represent any changes to that schema in code. This means that the state of your table schema at any given time is fully represented in your codebase's history. These systems are usually called Evolutions or Migrations.

I honestly can't imagine operating software against a SQL database without using a tool like this. They're very useful.

Mongo is Web Scale

There are a lot of database products out there! It's an exciting and interesting market and totally worth exploring to find the product that best fits the project that you're planning on building.

I'm fond of Mongo - because it doesn't enforce a schema on any of its documents.

One of the most important things to learn about when you're evaluating a new database is: what happens when I need more than one database server?

You don't need to distribute your data for scale up front. That is way premature optimization. Any database will get you to your first 10,000 users without needing to be distributed.

You do, however, need a failover plan, on day one. If your database goes down, what do you do? If your answer is "spend six hours loading a backup", that's fine - you just need A plan for this, because it will happen - and six hours of downtime is a lot of downtime.

Distributed Reads, Replication & Failover

One of the most basic and important ways to replicate data across servers - one that's available in just about every database - is replication to a secondary server.

This is a scheme where our primary server acts as a regular database, but it also streams all of its writes to backup servers. These backup servers cannot accept writes, except from the primary - if they did, there wouldn't be a way for any other servers to get those writes.

These backup servers are useful for two purposes - first of all, if something bad happens to your primary database, your primary database can fail over to one of the backup servers, which takes its place as the new primary.

The second thing that you can do here is perform slightly stale reads from the backup servers.

Most services do a lot more reads than writes, so distributing reads to secondary servers is actually an enormously effective scaling strategy - and this is one of the simplest models for database replication, so it's win-win!

However - if you think about it - because every write is distributed, first to the primary, then to all of its secondaries, each database in the cluster is absorbing the full brunt of all of the writes being taken on by your databases - this strategy can't scale writes at all.

But - we're not scaling yet. We're just providing a failover strategy - so that if our database goes down, well, there's another one, right there, waiting to take on the load.

Primary and Secondary

Up until fairly recently, the accepted term for the Primary and Secondary servers in a replication scenario were "master" and "slave".

This... sucks, but you might still encounter the terminology when exploring database products. Prefer primary and secondary.

Whoops, I Distributed Too Much Read Load and Now I Don't Have a Failover Strategy

One concern - let's imagine you're distributing read load to all of your secondaries, and they're all operating at just under 100% load.

Then, something happens to your primary, or even one of the secondaries: there's nowhere for that load to go. So instead your servers start to fail.

Guess what! You just triggered a cascading failure.

Whoops, The Secondaries Aren't Able To Keep Up With Writes and Now I'm Reading Super Stale Data

The secondary servers should be able to write exactly as fast as the primary server, but if they are dealing with so many reads that writes start to slow down, it's possible that they could start falling behind at processing their write load.

If the secondary servers start to fall behind, the data on these servers will start being more and more out-of-date. Things could get weird.

Whoops, I Read from Stale Data and then Wrote That Data Back To the Database, Overwriting Newer Data

Yeah, I've made a lot of mistakes with replication.

Distributed Writes (Sharding)

Replication can distribute read load, but how do we distribute write load? Since we're writing everything to every server in our cluster, write load is just going to grow and grow until our servers fall over - or we stop being popular.

One way is simply... not to write everything to every server.

If, for example, we have tables that don't join against other tables - say, EmployeeData joins against User, and ThumbnailFile joins against File, but these tables have no natural, in-database links.

There's nothing that stops us from simply hosting these tables on different databases. This is one of the strengths of databases that discourage joins - each individual collection can live on a totally different server cluster - it doesn't matter.

Beyond that, we can start looking at how even individual tables can be segmented across servers.

Take, for example, a UserPreferences table. Let's imagine that we have a whole bunch of user-id to user preference mappings in a big table.

| id | user_id | key | value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12344 | darkMode | on |

| 2 | 12344 | fabricSoftening | off |

| 3 | 34566 | darkMode | off |

Well, it would make a lot of sense to keep all of the data for a single user on a single database server - because all of our queries are going to query user preferences for a single user.

So our sharding might distribute users like this:

database A: users with an ID that starts with 1,2,3,4

database B: users with an ID that starts with 5,6,7,8

database C: users with an ID that starts with in 9,0

Then, whenever we write a user, we check which database to write it to, first, and only write to that database. Whenever we query userPreferences, well - we're only every querying userPrefences for one user at a time - so we'll run the query only against the server that matches the user we're querying for.

You'll note that both of the sharding schemes I've talked about here don't even require any cooperation from the database itself - you can literally just write your application to use a different database connection for different tables, or shard your data right at the application level. However - many database providers will give you tools to manage these strategies at the database level - which is convenient.

Let's look at some problems with our sharding strategy.

Lets look at how I distributed writes: using the first digit of the users' ID. There are two different problems with this strategy - first of all, let's imagine our user IDs are monotonically increasing over time - a common strategy for allocating IDs is just to count up, so every ID is going to be one higher than the last ID. That means that when we're writing new users to our database, we'll be writing users like this:

10901 (Database A)

10902 (Database A)

10903 (Database A)

10904 (Database A)

10905 (Database A)

...

Well... that's not distributed at all. We've distributed all of our writes to Database A. Eventually, we'll write 10,000 users and start distributing all writes to Database B instead, and then Database C, and so on!

This is a common problem with monotonically increasing values and shard keys - and a common resolution is to either select non-monotonically increasing ID values, or hash the IDs before we use them as shard keys.

10901 - 220A2BA5 - (Database A)

10902 - FB2C68A8 - (Database B)

Here, 10901 hashes to 220A, and that's very different from the next value's FB2C, so they'll distribute evenly across databases - in fact, we could have just used these hash values as the key in the first place.

Back to our sharding strategy:

database A: users with an ID Hash that starts with 0,1,2,3,4,5,6

database B: users with an ID Hash that starts with 7,8,9,A

database C: users with an ID Hash that starts with B,C,D,E,F

It still has a problem, which is that the sharding rules are unevenly distributing load across the databases. Database A in this scheme is always going to be working a little harder than the other databases. In fact, you'll note that you can't evenly divide the 16 characters of hex across 3 databases, because math - but this is resolvable by simply... using a longer shard key and sharding across ranges.

database A: users with an ID Hash from 0-33

database B: users with an ID Hash from 33-66

database C: users with an ID Hash from 66-99

Okay, now that we're at this point, how do we add a new server to the shard map? The answer to that question is it's a real pain in the ass. Schemes like consistent hashing can help, but by and large this is the value that having a database that manages its own shards brings to the table: it can rebalance shards when new shards enter the pool, without you having to manage that yourself.

Okay, new problem: what happens when we want to query for all userPreferences that are darkMode, regardless of user ID. We just want to count all the darkMode users in our application.

Well - the only way to do that is to split up the query, make it against every server in the cluster, and then, once we've gathered results from every server in the set, we merge them together. This is, notably, very expensive - sharding starts to become a losing strategy when you are working with data that doesn't have queries that clearly divide across servers.

Distributed Writes (Multi-Primary)

The common thread in both replication and sharding is the idea that there's still only one server at a time responsible for writes to any given unit of data. This dramatically simplifies enforcement of consistency around your data - so long as there is one source of truth about any given record in your database, you can trust that you'll never have to deal with write conflicts. There can't be two different histories for any given item, because all of the writes are ultimately resolved in one place.

However, some products allow writes from any server in the cluster. This introduces the obvious problem: what if two different servers write the same record at the same time? They've introduced a conflict, and with no authoritative primary server, there's no simple way to resolve this conflict.

You could just give write preference to whichever write happened first, discarding any conflicting write that happens after the write it conflicts with - but that wanders into the problem of "well, now all of the servers have to agree about exactly what time it is" - which, if you have learned a bit about distributed systems, is near impossible.

For a really long time, nobody even attempted to write databases that depended on strict synchronized time guarantees because they are so hard to do effectively. Google actually announced that they had built a database that resolved conflicts using synchronized clocks - which they accomplished by building atomic clocks directly into their data centers and carefully routing network connections to those clocks to keep clock skew to an absolute minimum. If you are not Google, this solution may be impractical - however, they proved that time-synchronization-based-conflict resolution is, in fact, possible - and an open-source version of that same solution, CockroachDB, is available today. This ties the performance of your write system to the quality of clock synchronization that you're able to achieve - which, even with the inaccurate tools available to us atomic-clock-lacking plebs, is still good enough for most production systems.

I think that's funny because clock-synchronization based solutions were once dismissed as impractical in all of the distributed systems textbooks.

Other systems achieve multi-primary writes by sacrificing consistency - at some point they'll just have to guess which write was the correct one, and you have to hope that the system guessed right.

Still other system achieve multi-primary writes by using specialized data structures - Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types, or CRDTs - these data structures contain complicated rules for how to resolve all possible conflicts in their writes. The data structues themselves are based on some very math-laden papers describing a system called Operational Transformation, and they were designed initially to resove conflicts in spaces where users would definitely and unavoidably be trying to write the same data at the same time - synchronized documents - Google Docs, essentially. The consistency offered by these rules is predictable - given the same set of inputs, the data will always come out the same way - but that doesn't necessarily mean that the automatic conflict resolution is always seamless or what a human would expect.

Systems offering multi-master replication - systems like Cassandra, CockroachDB, DynamoDB, BigTable, Google Cloud Spanner - are almost always the most scalable, full stop, no question - but, with that, they bring a lot of the additional complexity of managing cluster-first databases.

It's often much better to build your products on the comparatively simple primary/secondary databases we all know and love, and not move to a multi-primary database until you have lots of people and money to manage the extra complexity involved.

UUID

In many systems, its possible to know, when you do a write, what the highest ID value is in your database right now, and then, write to the next highest ID - if you're creating a user and the last user created was 19283, your next user can be 19284.

However, some databases - multi-master in particular - can't offer this guarantee - if you want to be able to tee up writes without that back and forth between you and the database, you'll have to be able to provide an ID that you can guarantee doesn't already exist in the system.

This is where the UUID comes in handy. They're long, and random, and look like this:

6ead48e0-c795-49bd-9e28-bdee980caf87

The magic of the UUID is just in how random they are. They're 128-bits of randomness - If you generate 2 UUIDs, they won't be the same. If you generate 1 million UUIDs, they won't be the same. The chance of a collision in the UUID space is so microscopic that you'd have to generate a billion UUIDs per second for about 85 years to see one.

UUIDs aren't totally collision-proof - collisions, though, are usually the fault of failures in the implementation of the randomness that goes into generating them rather than in the space that they occupy, which is unimaginably vast. This makes them an awesome choice for identifying any data that you want to have a non-monotonic, unique, well-distributed identifier for. This also makes them pretty excellent shard keys.

Other Backing Services!

The database is such an important part of modern web applications that it would be silly not to talk about them. You, of course, can run web applications without databases - but few do. That shared nothing model means that you have to work around having essentialy no permanent memory between requests, so the utility of an application that can only remember the last 5 milliseconds is limited.

Databaseless applications might do something like perform a single task on every call - a random character generator for a game could split out a totally new and different random character every time you visit it without needing to remember anything. Proxy servers, being as they just forward requests to a third party and then get back to you, also don't need any permanent memory.

This variety of service, when it's useful, can be scaled very easily, which is nice.

But... well, most services require more stuff than that, and databases alone can't provide everything that the services require. You might need file storage, or message queues, or you might have data that doesn't fit cleanly into a tabular data storage system.

So, let's talk about some of the other things you might connect your web server to:

Files

You're going to need to store more than just data in your web service. There's a chance that you'll also have to deal with files. User thumbnails are a particularly common type of file to have to deal with.

You'll also be backing up your database - presumably - and you'll need a place to keep those backups.

Most databases are configured to store a lot of very structured, little data, not a lot of very unstructured big data - they're more intended for user records than audio files.

Storing files can be very simple, or very complicated.

The simple way to store files is just to stash them on a server, making sure to back them up to a secondary server, every now and again, and serving them using something like the NGINX web server.

You can get a little more complicated than that - sync the files to multiple servers, and load-balance access to those files using NGINX again.

These strategies start to tap out a little bit once you're storing more files than you can fit on a single server - somewhere in the 20-1000 gigabyte range you're gonna have to start thinking about infinite file storage.

A lot of cloud providers offer infinite file storage, with backups, and access-controls, and load-balanced hosting of those files - products like S3, Google Storage, or Wasabi - this is something you'll probably set up with them rather than running it in house, because it's a complicated thing to set up and manage.

There are also in-house protocols, like Ceph, you can use to set up this kind of thing on your own, but they're very complicated products - generally intended to be set up at the service provider level rather than by anybody who comes along and wants to spin up an individual product on their own.

RAM

Databases, even multi-master ones- still have to write everything to disk, and back it all up.

There's some data that you don't need to do all of that for. Ephemeral data.

And there are databases out there that don't store anything. They just boot up, exist in your machine's RAM, and when you turn them off, they stop storing anything.

These databases are stupidly fast. I mean, obviously - they don't have to write any data, they just have to keep it floating around until you need it.

This is particularly useful for cache - when you have complicated procedures that take a lot of server time to complete and you want to save their result for a few seconds, or a few minutes, or a few days so that nobody else has to perform that complicated procedure again.

Some classes of data are legitimately pretty ephemeral and come with limited consequences if they get eaten in a server crash - user sessions are very temporary and need to be accessed on every single user interaction, so fast ephemeral storage is a good place for them.

This is the wheelhouse of services like Redis, and memcached.

It's important to note here that the gap between ephemeral services like Redis and multi-master database services like Cassandra has been narrowing over time. If you're configuring your database servers to perform most operations directly out of index anyways, you don't gain much speed by skipping the write step - I have a friend who just uses DynamoDB for everything because, correctly configured, it offers single-digit-millisecond response times. On the other side of the table, Redis can be configured to stream all of its writes to disk, giving users recovery options and backup options if their servers ever do go down.

So, fast databases can act like cache, and recoverable cache can act like a database.

Queues

Your web servers should not be doing CPU intensive processes. Or long-running processes. Both of these interfere with their ability to do the one thing that they are supposed to be doing, all of the time: quickly responding to as many requests as humanly possible.

So, when we have a long-running or CPU intensive process, we need to do it somewhere else - which means that we need a way for our servers to queue up background tasks.

We can just use our databases or our cache to resolve this problem - but, there are, of course, products designed specifically for this use case - message queues. Products like RabbitMQ, designed to hold on to messages, and have lots of servers subscribe to those messages.

Messages, once enqueued, can be delivered just once, or redelivered until they're guaranteed to have been processed, eventually rolled into a dead letter queue if they fail repeatedly, there are lots of tools for managing these messages.

Streams

Streams and Queues are only subtly different as data structures, but they serve different purposes.

A lot of data - logs, for example - can be streamed, just sort of written very quickly in order. Many different consumers can then keep a pointer to where they were reading on the stream, and just read whenever they want, updating the pointer as they go.

This data is still structured like a queue, like the message queues we just talked about, but there are no guarantees that data will be read out of the stream, or delivered at all.

Streams are more popular for things like structured log data, where lots of consumers might potentially read from a stream. Systems like Apache Kafka and Redis provide Streams.

Time Series Database

An even more specialized instance of a streaming database is a time-series database. Time series databases are intended for the problem of analytic data - writing absolutely enormous amounts of information and then, compressing that data over time so that even more data can be stored - you are probably more interested, for example, in high-granularity diagnostic information for the last five minutes, and lower-granularity diagnostic information for the last five years.

Products like InfluxDB, Prometheus, and VictoriaMetrics provide time-series databases.

Search Databases

Another specialized database type that you might add to your infrastructure is a search database.

These operate like a kind of specialized index server that provides extra indexes for your database. When you write to your database, you'll also write index updates to your search index provider. Then, when users search your data, they can use the more powerful search features in the search provider - this often produces faster and more accurate search results than the results that you'll be able to achieve with simple database queries.

Products like ElasticSearch provide search capabilities.

I Love Redis

I just want to toss a little special extra love towards Redis - with relatively sane clustering, incredibly fast memory-based operation, optional backups, and support for queues, streams, and search, it can do a lot of things, pretty well. You should probably not use Redis as your primary database - it's really not designed for that -but as a secondary database it can pull a lot of weight in your infrastructure.

Some Sane Defaults

If you're looking for a sane set of defaults for a new product, consider

- Postgres for your primary database, expandable to CockroachDB if you need something much more scalable.

- Wasabi for your files and backups.

- Redis for your cache, streams, queue, and search.

- VictoriaMetrics for your metrics, as a time-series database.

Of course, you shouldn't introduce services until you know that you'll need them.

Also, by the very nature of time, this segment may be badly outdated by the time you're actually hearing it - so, before taking my word for it, you should absolutely go do this research yourself.

Local Environment Automation

Now that you've selected language for your web service to run in, and a suite of technologies for your web-service to connect to, your next step is to painstakingly and by hand install and configure all of those technologies on your computer one at a time - wup, no, that's not it.

Your actual first step is to use your local automation framework to set up and tear down your entire local environment. Here, tools like virtual machines and docker containers are your friend.

I used to do this with invoke and Vagrant, now I do it with jake and Docker Compose. You can do it with pretty much whatever you want - so long as you can open your project on an arbitrary computer and have it set up its environment for you, you're good to go.

As a freebie, you are allowed to expect that your language and virtualization tools already exist on the target computer. Make sure to call out those local installation dependencies in your repository's README.

Connect & Config

The first thing your application will do when it boots up is to connect to a variety of services - databases and the like - and then set up its router and start routing requests.

This is an important step - building database connections is an expensive task, so your system definitely should not be building a fresh database connection for every request - instead, when your system boots up, that's when it builds all of the connections it's going to need for the lifetime of the process.

Because our servers are ephemeral - shared nothing - it's good to try to keep this connection step fast - that way, if something bad happens, the servers can just quickly reboot, reconnect to its backing services, and go on their merry way - in fact, you can set up your application to just fail with an error code if it ever loses a critical connection - instead of building reconnection logic, your application's supervisor will just reboot the application again and again, until it eventually manages to reconnect properly.

If we're connecting to a lot of other services, though, we need their locations, their credentials.

Obviously, we shouldn't hard-code these locations into our product. I feel like that's such a basic observation that I almost feel silly saying it.

Prefer URLs for Locating Resources, Uniformly

Have you ever seen a block of code that looks like this?

database_protocol = 'postgres';

database_host = 'localhost';

database_port = 1234;

database_user = 'gork';

database_password = 'mork';

database_name = 'application'

Yeah, that's a line of details that you'll need to connect to a database, and six whole different variables.

If only there were some sort of uniform way to represent the location of a resource.

Of course, what I'm leading you to is that this is another use of our old friend the URL. We can take that whole set of connection details and squish it together into one neat, tidy URL:

postgres://gork:mork@localhost:1234/application

URLs are great when it comes to providing the unambiguous, complete location for a resource somewhere on the internet - which is - exactly what you want to provide when you're connecting to backing services.

Config Files

A common strategy for managing your configuration details on start-up is to maintain a set of reasonable defaults, then, parse a config file located somewhere in the system. The config file might be represented in INI, or XML, or JSON, or YAML, or TOML, really any user-editable serialization format should do the trick.

Of course, you don't necessarily want to hardcode the location of the config file - then you won't be able to run two copies of the same application on the same system - and you might want to change individual variables up when you boot up the application.

For this, we want something a little more flexible than config files.

Environment Variables

So - and I'm biased here, I think this is the best way to set up configuration information for your app - you can just pass in all of the configuration as key-value arguments when you boot up the application.

You can either do this by setting up and parsing arguments passed to your server software when it boots up - like

>>> myserver --databaseUrl=postgres://blahblahblah

or, and this is extremely well supported on Linux systems, you can pass them in as environment variables:

>>> MYSERVER_POSTGRES_URL=postgres://blahblahblah myserver

One of the really nice things about environment variables is that you can set them permanently for a bash session - so if you're coding and you want to change the postgres environment for your next ten runs of the application, you can set that environment variable and it'll be passed, automatically, to your application.

A lot of testing frameworks, application supervisors and containerization solutions for deployment also give you fine-grained control over which environment variables are passed in to your application when it boots - making this a super well-supported way to handle flexible configuration for your application.

Database Config

All of these solutions are well and good for taking hardcoded variables and instead passing them in when you boot up your application.

However - these values are locked at boot time. Your application is likely to be put up and left running for weeks or months at a time - you don't always want to have to reboot and rerun all of your servers to make a simple config change.

So, for variables that you want to be able to change frequently, I recommend storing that information in your database, in a configuration table. You probably shouldn't do this with database connection details, but for a lot of other things it's super useful - in particular, this supports feature flags really well.

One thing about config, though, is that these variables tend to be hit very, very frequently. I don't usually advocate keeping anything in your servers' local memory - but - because config is small - I think that the best way to maintain a fast, reliable config is to have every process in your entire cluster cache a full copy of the entire config object in local memory and refresh it periodically.

That might not be necessary, though - how you deal with config is up to you.

The Config Heirarchy

Okay, so, for every hardcoded variable in your system, there's a potential four-step heirarchy of where that value could come from, each overriding the next:

- Default

- Config File

- Environment Variable

- Database Config

And you don't need all of these for every application - I think that Config File and Database Config are both a little heavyweight for little applications, and the Database Config doesn't necessarily need to be able to override everything in the Config File - especially connection urls.

Authentication

Now you've got your services all set up, you're booting up a web server, and you're connecting to them! Now what?

Well, now you have to write the same awful thing that constitues 90% of all web programming forever: authentication. That's what we do here, we tirelessly reinvent wheels, and this is a wheel you'll have to reinvent, too.

People are going to need to register to use your site, login, log out, recover their accounts, all of the basics.

Passwords

So, a user creates an account by giving you a username and password.

Well, we already have a problem, just up front, we can't store a password in our database. What if someone gets access to our database? What if we get access to our database? Aside from credit card numbers, passwords are some of the most sensitive user data we can get access to, so we have to be unusually careful with them. (As for credit card numbers: just don't store those - if you think you're in a position where you need to, you probably don't. )

There is an interesting property of hash functions that we take advantage of to store passwords without actually storing those passwords.