I am Rubén Sardón, student of the Bachelor’s Degree in Video Games by UPC at CITM. This content is generated for the second year’s subject Project 2, under supervision of lecturer Marc Garrigó.

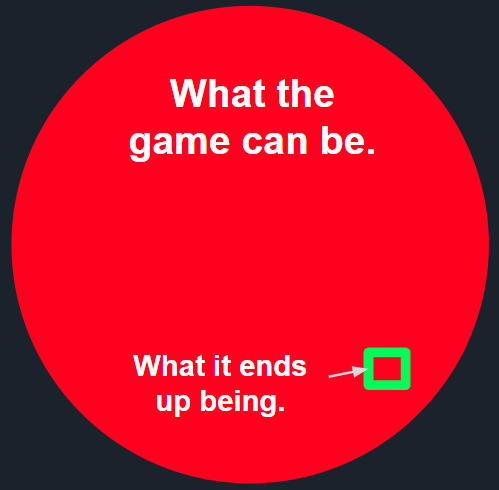

Having a clear idea of a game you are trying to make is impossible. Everyone in the team has a different idea of what the game may end up being. It leads to chaos. The best approach is to start by agreeing on a set of concepts that define what the game is going to be about.

Game pillars are these set of features or concepts that define the game and help guide its design process. These bounds are especially important for teams as they make sure everyone has a clearer idea of the game. They are unchanging concepts and ideas set and agreed upon before designing any feature.

Let's take a look at some nice examples of video games and their game pillars.

- Combat

- Choice

- Narrative

- Characters

In this rpg players decide whether to kill, flee, or befriend monsters that challenge the player in combat. It forces the player to choose as the player progresses though the story. Winning a fight rewards players by letting them stir the story’s direction.

- Music & Rhythm

- Items & Weapons

- Enemies

This game is all about clearing dungeons at the beat of the music. You use many unique weapons to defeat all kinds of monsters. You fight against a huge variety of monsters with different behaviours. The simplicity of just 3 main pillars makes it easier to understand what the game is about yet still allows huge room for complexity.

- Crafting

- Story

- AI Partners

- Stealth

This one is a survival horror game where the player combats enemies and scavenges for crafting materials. These encounters allow for a tactical advantage using stealth instead of just going ham. Crafting compliments player progression through the campaign. The story is pushed mainly through conversations between characters. The player will build a relationship with these characters as he encounters them.

- Exploration

- Movement

- Scavenging

- Options

Here players are given little instruction and set off to explore freely a massive open world and a non-linear story. It always allows the player to approach a challenge any way they want. The main task is to collect different tools. These multipurpose tools allow the player to interact in new or different ways with the world; many make moving easier in a certain way. Improving movement allows for further and more efficient exploration as the player progresses. Other tools like weapons have durability and will break after being used too much. Having limited inventory space and stuff breaking forces the player to look for resources constantly and deciding which to pick up.

- Approachable

- Powerful Heroes

- Highly Customizable

- Great Item Game

- Endlessly Replayable

- Strong Setting

- Cooperative Multiplayer

A hack-and-slash RPG. It's all about stats and mechanics; building your hero to as strong as possible to defeat enemies and bosses. How the player builds its hero sets how he is going to play. As the player progresses he gets exponentially stronger and gameplay becomes way more dynamic. Diablo had very strong and concrete definitions about what the game was going to be. Being highly customizable and endless leads to huge a huge variety of mechanics; and, to counteract this complexity they set approachable as the first game pillar.

It is common to mistake game pillars as Key Selling Points. KSPs are specific concepts or features a customer may be interested in when purchasing a game and game pillars are broader definitions of the game that partake in all design decisions. They are not adjectives, tasks nor technical concepts:

- simple

- complex

- pretty

- dark

- fun

- random

- optimized

- polished

Once we decide and agree on our games’ pillars we can have a more focused approach when coming up with design ideas. At the beginning of designing a game the constraints of what can be done are not clear and especially when entering a new team; game pillars will be the only point of reference. We must analyze all ideas to figure out which suits us better. Check for these when designing or modifying a feature:

- Concordance: Does it contradict pillars? Does it push forward what our game is about?

- Effectivity: How much will it change the game? What problem does it tackle?

- Efficiency: How long will it take to make? Is there time to make it?

- Relevance: How important is it to the game?

At later stages of production, design decisions will become more challenging as systems become more complex. Designers must adapt to production challenges as systems may not end up being what they envisioned. When designing a feature on later stages be sure to include:

- Quality Assurance: How do I check it works?

- Contingencies: If something doesn’t work, how can the design be changed? Could it be discarded?

- Conflicts: Does it contradict or affect any previous systems?

This procedure allows the team to make better decisions for the game. Judging and analyzing your own design ideas grant you and your team a clearer understanding.