Developed by Deep Tronix 2018~2021

A (hopefully comprehensive) guide to the library.

The main goal of this library was to recreate the most popular dithering algorithms (filters) developed and used back in the days where this technique was used the most. It aims to get you from the RAW image to the dithered one as quickly as possible (meaning in complexity of using the library, but also in code optimization).

To do so, I researched the web; back in 2018, when I started this project, a website (no longer alive today) explained in detail the different error-diffusion filters and their corresponding weights.

I managed to save a copy of the content; it can now be found here.

This youtube lecture is also noteworthy, regarding an intuitive and more graphical understanding of dithering and halftoning.

Following that document, I managed to develop the different algorithms, now collected in the presented library.

Dithering is nowadays a technique only used in 2 scenarios:

- the display/printing hardware is color-limited, but the processor has spare processing time

- The requirement to be fulfilled is the “old-style”, vintage look, like the one from old newspaper.

Let's start with the most common and, to me, most pleasing dithering techniques.

The core of the error diffusion algorithms is a function called “_GPEDDither”, which stands for “General Purpose Error Diffusion Dithering” (the underscore highlights that it is under the private section).

As a way to keep in order the various algorithms, I decided to call it only from specific functions, which have the names of the filter applied. The available error-diffusion dithering algorithms are:

- Floyd-Steinberg

- Jarvis, Judice, and Ninke

- Stucki

- Burkes

- Sierra3

- Sierra2

- Sierra-2-4A

- Atkinson (not found in the document, but available here)

- a personal filter, of which the coefficients can be customized, for example by taking inspiration from other filters. By default, the values are set up so as to emulate a simplified and more “constrasty” version of the Atkinson filter.

Since the GPEDDither function is the same for all the algorithms used, there are two key points to notice:

- The function cannot easily be optimized any further, without knowing either the microcontroller's instruction set or other simplifications. For this reason, the function is clearly not as efficient as a filter-specific version of the same.

- The filter coefficients are stored in an array (actually, a matrix) in the “Dither.h” file; the arrangement can seem a little confusing at start, hence I decided to dedicate the next section to explain it, and also allow for editing.

- A "quantization_bits" input parameter is available if you have a display that supports gray shades. In this case, dithering allows for much smoother gradients that would otherwise result in harsh gray-shading lines.

In order to take full advantage of the capabilities of this gray shading+dithering technique, you are supposed to enter a number of bits equal (greater wouldn't make a difference) to the bits of gray-shading available in your display (e.g.: using my EPD gray-shading library, which allows for 8 gray shades, you should use one of the dithering functions with quantization_bits set to 3).

Note: all of the functions seems ready to also accept color inputs (on many lines, green and blue color variables have been commented out, but are there); however, I could not test the library with those parameters for a lack of time and hardware resources, so I decided to leave them disabled.

Coefficient arrangement for different error-diffusion algorithms (found in Dither.h):

Example:

const int8_t _filters[filter_types][max_filter_entries] = {

{16, 7, -1, 3, 5, 1, END}, // Floyd-Steinberg filter

{8, 1, 1, -1, 1, 1, 1, -1, 0, 1, END}, // Atkinson filter

…

};

Array observations:

- located under the 'private' label, so it's not accessible from outside the library

- It's defined as const, which means it's not editable on-the-fly. It's stored on program flash

- It's signed, since positive values are used as coefficients and negative ones as position markers

- Filter entries are related to their corresponding algorithms through the macro names-to-line number (e.g.: FSf (Floyd-Steinberg filter), JJNf, …, ATKf). If order is changed or entries deleted, the corresponding macro lines are to be changed accordingly.

Values arrangement explanation:

- The first value (location '0' of each matrix line) is the DIVISOR. This value is used to “normalize” the weights applied. Note: The GPED function will try to optimize on its own divisions by power of two into bitshift operations whenever possible. This comes at the cost of checking, at each pixel, if this condition is satisfied. If you know you will be using a known power of two divisor, or a MCU with hardware division, you can remove the lines of code that choose the division method.

- Each successive value is either:

- a positive value: this represents an error-diffusion weight. The neighbouring pixels to the one currently analyzed will be multiplied by this amount (and then divided as in point 1) )

- a negative value: the fact that is negative represents a “linefeed” command (meaning the next pixels to be processed are from the line below). The absolute value is the amount of pixels by which the horizontal “cursor” needs to move (to the left).

- The constant labeled 'END', which indicates the filter has been exhausted.

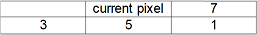

Example #1: Floyd-Steinberg error diffusion (note: by “pixel examined” we mean the current pixel, the one whose error is distributed amongst the neighboring ones)

Filter entries: {16, 7, -1, 3, 5, 1, END}.

- 16: each value, after being multiplied by its weight, will be divided by 16

- 7: the first weight, by which the pixel to the right of the one being examined will be multiplied

- -1: command “go to next pixel row” , by 1 pixel to the left of the one examined

- 3: the second weight applied to the pixel 1 line below, 1 column to the left of the one examined

- 5: the third weight applied to the pixel 1 line below, at the same column of the one examined

- 1: the fourth weight applied to the pixel 1 line below, 1 column to the right of the one examined

- END: value compared beforehand, used to terminate error distribution work.

( :16 )

Example #2: Burkes error diffusion

Filter entries: {32, 8, 4, -2, 2, 4, 8, 4, 2, END}.

- 32: the division factor

- 8: row 0, column 1 weight

- 4: row 0, column 2 weight

- -2: linefeed: go to next line (row = 1), start at column -2

- 2: row 1, column -2 weight

- 4: row 1, column -1 weight

- 8: row 1, column 0 weight

- 4: row 1, column 1weight

- 2: row 1, column 2 weight

- END: terminate error distribution.

( :32 )

Note: when some pixels are skipped (like in Atkinson dithering), or if the next pixel to be processed is one line below, but at the same column of the one being examined, weights with value '0' are used to skip the step.

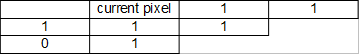

Example: Atkinson dithering; filter entries: {8, 1, 1, -1, 1, 1, 1, -1, 0, 1, END}

( :8 )

The reason behind this function is optimization. With this function, the goal is to improve the overall image perception, even when a low cost processor is being used. After all, this technique was born in times where both processing power and display color accuracy were highly limited.

The cost of such high level of optimization is payed with the limited range of customization of the output image look; the main constraints with this approach are:

- No choice of output bit-depth: the output is a fixed 1-bit (actually, 0/255) value

- Only 1 compatible filter choice: a (modified) Floyd-Steinberg filter

The function rewards the user who chooses to accept these limitations in favor to the time taken to exhaust the image array.

This function takes, on average (and with a sufficiently good compiler) about 90 clock cycles per pixel processed; this translates to about 10-20 times less clock cycles than the aforementioned GPED function (for a Floyd-Steinberg filter; other filters take longer proportionally to their number of weights).

For example, an ATMega2560 running at 16MHz will process a 128x32 BW image in about (90 * 128 * 32) / (16 * 10^6) = 23ms, while the same image processed using the GPED function could take up to roughly 400ms.

A “modified Floyd-Steinberg” filter was mentioned. To further reduce clock cycles usage, the filter applied to the neighboring pixels (in the arrangement explained in the GPED filter section) is as follows: {2, 1, -1, 0, 1, END}

( :2 )

However, there have been noticed some artifacts (especially on images bigger than about 8000 total pixels) due to the simplicity (and somewhat recursivity) of the weights location, hence a macro located in the file “Dither.h”, named “fastEDDither_remove_artifacts” can, at the cost of some additional clock cycles per pixel, alter slightly the structure so that it gets closer to the real FS filter matrix. The new filter matrix will then be: {2, 1, -1, 0, 0.5, 0.5, END}

( :2 )

These filters, although depicted here in a similar fashion as the GPED matrix, are not explicitly visible as a parameter in any part of the two library files; this is because they are implemented as bit shift operations deeply embedded inside the fastEDDither function. So do not expect to be able to change the values applied as easily as in the GPED dither approach.

The two main algorithms developed in this library make use of a clustered and a dispersed (Bayer) convolutional matrix pattern.

In order to use this algorithm (whose function is called “patternDither”), one of the matrix-filling functions must be called beforehand in order to put the coefficients at their correct locations.

In order to do so, you are provided with two functions, called “buildClusteredPattern” and “buildBayerPattern” which, according to the macro “_size” found in “Dither.h”, fill the entries of the matrix, and allow the dithering function to be used. If neither of the two filter-filling functions gets executed before the patterDither function, this last one will stop immediately and return “-1”.

Still, as soon as one of those functions is executed, the matrix entries will be saved in RAM so no additional call needs to be made, until power is lost or RAM is corrupted in other ways (e.g.: going to deep-sleep). A valid approach, then, would be to call either “buildClusteredPattern” or “buildBayerPattern” in the first section of the main, and then only use “patternDither” in the while(1){} section.

The “_size” parameter dictates how many row/columns of the (square) convolutional filter matrix are to be used.

Theoretically, the number of output gray shades obtainable for a given choice of “_size” is:

[1 + (_size)^2]. Literature papers and experiments show, however, that matrices bigger than 3x3 yield unnoticeable improvements. In contrast, the higher the _size of the matrix, the bigger the final dithered (clusters of) “pixels”, leading to a lower overall resolution.

On lower-end uCs, though, it's recommended to use values of _size powers of two (so either 2 or 4); this is because the compiler will be able to optimize modulo operations performed in the patterning function.

Example usage:

image.buildClusteredPattern(); // build a clustered pattern (fill the convol. matrix)

*...some code, or nothing...*

image.patternDither(img_array); // dither the image array

// no need to call build___Pattern ever again

No dithering library would be complete without this algorithm, which represents the very first approach used to dither.

The only thing this algorithm does is compare the value of the current pixel with a random value. The output value, with which the pixel is substituted is obtained as the result of the comparison itself.

The implementation presented of this algorithm, though, has a couple of degrees of choice:

-

a variable “time_consistency” can be fed alongside the input image array as a function parameter, which if set to “true” makes use of a pre-filled random array of values; this both increments speed (since random value generation on the fly would otherwise be obtained using timers and delays), but also makes this dithering approach more time-consistent (frame-by-frame), especially useful for animations. This variable is already set up to be used, true by default, as can be seen in the definition of the function “randomDither” in the “Dither.h” file.

-

a second variable “threshold” can be set, which essentially offsets the comparison either positively or negatively, with a value inside the interval [-128 : +127]. A positive threshold will make the image appear darker.

This variable is also already set by default in the function definition, but is set to 0 in order not to modify the look of an image if not explicitly expressed. -

The parameter “_rnd_frame_width” found in “Dither.h” will dictate how long the array of pre-filled random values is going to be. This is crucial in order to avoid artifacts, that will emerge if too short of an array is used (basically, the comparison numbers inside each image line will be repeated). A value equal or greater than the image width is recommended; the only cost for higher values of this variable is the use of RAM memory (the array type is uint8_t). Due to code optimization, the only values allowed for this variable are powers of 2 (64, 128, …); this way the modulo operations can be done via bit shifting.

-

The parameter “_use_low_amplitude_noise” found in “Dither.h” will tell the compiler which noise generation approach to use once running. Performance-wise, setting this variable to either true or false will yield the same results. On the image quality side, though, it's been noticed that, except very specific cases, low amplitude noise performs better than high amplitude noise. This is probably due to the fact that low amplitude noise resembles more a Gaussian (Normal) probability distribution, and after a “low-pass filter” (your eyes at a distance), the image is more pleasing. We recommend to leave this variable set to true, unless you specifically notice dithering results to be almost not affected.

Example usage:

- image.randomDither(img_array); // dither with time consistency enabled and 0 offset

- image.randomDither(img_array, false); // dither with time consistency disabled and 0 offset

- image.randomDither(img_array, true, 15); // dither with time consistency enabled and +15 as offset

- image.randomDither(img_array, false, -10); // dither with time consistency disabled and -10 as offset

This function could actually be omitted; thresholding is not a part of dithering algorithms, but it was added to the library mainly to be used in comparison with the dithering functions. Sometimes, also, on particular screens and modes of operation (e.g.: animations), thresholding might actually perform better than dithering. Take this (real) case study: on an e-paper display, where pixels take no less than 250ms to settle to their new color, an animation is asked to be played.

If error diffusion algorithms are used, single pixels change frequently from frame to frame and hence cannot settle and correctly represent the color. Even pattern dithering, which supposedly is more appropriate for this task, is not time-consistent enough. The image always appears too faint (low contrast). In this case, it's been noticed that both random dither and thresholding produce a better image which, even though has some details removed due to lack of output color accuracy, is still recognizable and, most importantly, has high contrast ratio.

Besides, given the lack of processing resources needed to perform thresholding on each pixel, this function operates extremely quickly on image arrays, with a cycle count per pixel processed of about 20 (¼ the time taken by fastEDDither).

This function allows for thresholds different from 128; this is the default value, but a different one can be given as the second parameter to the function to change its value.

Example usage:

- image.thresholding(img_array); // apply thresholding to image, at level 128

- image.thresholding(img_array, 140); // apply thresholding to image, at level 140

Here we list the other functions, some used in the library, others ment to be used it your implementation (e.g.: color bit depth conversion, indexing, …), others still already set up for future expansion of the library (such as support for different, higher output bit depths than 1).

NOTE1: all of the color conversion function operate on a single pixel. If you have to convert an entire image before dithering or displaying/printing, you need to step through each pixel and convert them one by one.

NOTE2: Not all the available functions have been tested, since I didn't have the hardware to do so. If you notice weird results, blame them before anything else.

void Dither(int width, int height, bool invert_output);

This function is the object constructor, and can be provided with the image width and height. Still, if only some helping functions of the library need to be used, that don't require the definition of a specific width and height, you can call this constructor without any parameter.

An additional parameter, "invert_output" is used if the output of choice is not a display, but rather a printer (in which case, black and white colors are often swapped; although most printers will treat '1' as black by themselves). This parameter can be omitted, and it will be disabled by default.

See the provided example to see how it's used.

void updateDimensions(uint16_t new_width, uint16_t new_height);

This function can be used to update the image dimensions; if you only need to update one dimension, not knowing what the original dimensions are, you can use the following 'get' methods to interrogate the internal private variables.

uint16_t getWidth();

Returns the current image width dimension.

uint16_t getHeight();

Returns the current image height dimension.

void reRandomizeBuffer();

Takes the internal random buffer which is used for the function "randomDither" (in particular, when 'time_consistency' is enabled) and populates it with new random values. Can be useful if you want a temporal consistent random dithering, but need to sometimes change the random pattern applied.

uint32_t index(int x, int y);

Takes the two values for x and y coordinates (x = 0 → pixels to the far left; y = 0 → pixels at the top) and, implicitly, the values of image width and height provided in the constructor.

Returns the array index corresponding to the pixel at location (x, y).

NOTE: this function operates assuming a byte-aligned image array. If you are working with 16 or 24 bit images, the pixels are not correctly indexed. For those images, use the overloaded function below.

uint32_t index(int x, int y, uint8_t pix_len);

Takes the two values for x and y coordinates (x = 0 → pixels to the far left; y = 0 → pixels at the top) and also how many bytes each pixel is represented by. Implicitly, takes the values of image width and height provided in the constructor. The parameter “pix_len” is in range [1, 2, 3], which correspond to [8, 16, 24] color bit depths.

Returns the index of the first pixel byte at location (x, y) of the image.

uint8_t color888ToGray256(uint8_t r, uint8_t g, uint8_t b);

Input arguments are the RGB colors of a pixel, in the format RGB-888.

Returns the average of the 3 pixels (hence, the resulting image will be gray scaled).

void colorGray256To888(uint8_t color, uint8_t &r, uint8_t &g, uint8_t &b);

Input argument is a gray scale, 8bit pixel.

RGB values are also parsed as inputs and accessed (and modified) by address.

Note: obviously, this function cannot restore individual R, G and B components. Keep in mind that the purpose of all of these functions is just to make pixels compatible with algorithms and displays.

bool colorGray256ToBool(uint8_t gs);

Input argument is a gray scale, 8bit pixel.

Returns a boolean value, formally equal to a threshold applied with comparison value 128.

void color565To888(uint16_t color565, uint8_t &r, uint8_t &g, uint8_t &b);

Input argument is a color, RGB-565 pixel.

RGB values are also parsed as inputs and accessed (and modified) by address.

uint16_t color888To565(uint8_t r, uint8_t g, uint8_t b);

Input arguments are the RGB values.

Returns the 16bit, RGB-565 value.

void color332To888(uint8_t color332, uint8_t &r, uint8_t &g, uint8_t &b);

Input argument is a color, RGB-332 pixel.

RGB values are also parsed as inputs and accessed (and modified) by address.

uint8_t color888To332(uint8_t r, uint8_t g, uint8_t b);

Input arguments are the RGB values.

Returns the 8bit, RGB-332 value.

void colorBoolTo888(bool color1, uint8_t &r, uint8_t &g, uint8_t &b);

Input argument is a single boolean value.

RGB output values (in RGB-888 format) are also parsed as inputs and accessed (and modified) by address.

This function is mainly used for final display output.

bool color888ToBool(uint8_t r, uint8_t g, uint8_t b);

Input arguments are the RGB-888 colors.

Returns a single boolean value obtained as the average of three colors, and thresholded at 128 ( true when >= 128 ).

This function is mainly used for final display output.

inline void quantize(uint8_t quant_bits, uint8_t &r, uint8_t &g, uint8_t &b);

Quantization function used to limit the input values to the closest quantization level.

Input argument quant_bits defines how many bits will be used to quantize the input values; r, g, b values are parsed and modified by address.

Defined as 'inline' in order to avoid too much overhead, since the function is very short and not supposed to be used outside the library.

inline void quantize_BW(uint8_t &c);

Simplified quantization function, used only in fastEDDither to speed things up since the quantization output bit depth is predefined and fixed at 1.

uint8_t _twos_power(uint16_t number)

Used to get the exponent of a power of two number. Basically, operates the logarithm in base two of a known-to-be-power of two number.

uint8_t _clamp(int16_t v, uint8_t min, uint8_t max)

Used to clamp an input value between two positive, 8 bits, values (always 0 and 255 in this library).