- Introduction

- Ethical considerations

- What is 'stalkerware'?

- What are 'dual use' apps?

- How does stalkerware work?

- Who are the players?

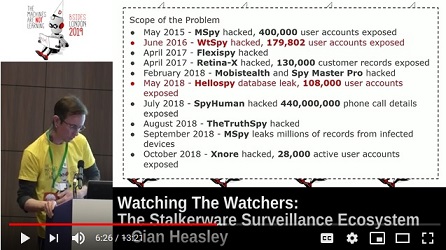

- Insights from leaks

- Signs of infection

- What is to be done?

- Further reading

In 2017 Rasheeda Johnson Turner was arrested in Los Angeles for hiring a hitman to kill her boyfriend in order to cash in on his life insurance policy, she had installed monitoring software on her boyfriend's phone so that she could inform the hitman of his movements. Last year during the trial of drug cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán it emerged that he had installed the "FlexiSpy" stalkerware app on 50 "special phones" as he called them, which he gave to his inner circle so that he could monitor their communications unbeknownst to them.

Prosecutors in the triple homicide case against Luis Toledo were able to prove that he had installed stalkerware called "SMS Tracker" on his wife's phone before her death, what he discovered motivated him to kill not only her but her 8 and 9 year old children as well. Toledo is currently serving three consecutive life prison sentences for the murder of his family.

Cooperating with Europol and Eurojust, law enforcement in Germany, France, Britain, Belgium, Switzerland and the US carried out raids on users of 'DroidJack' in 2015, a sort of combination RAT (remote access trojan) and stalkerware, an arrest in the UK was covered by the BBC at the time.

Carlos Enrique Perez-Melara was added to the FBI's most wanted list in 2013, for creating and marketing "Loverspy", stalkerware that masqueraded as an electronic greeting card but was in fact malware designed for harvesting victim's messenger app content, emails and monitoring their webcam, transmitting the data back to the software's purchaser.

Kristin Newell Nyunt pled guilty in 2014 to two counts of wiretapping for installing "Mobistealth, StealthGenie and mSpy, on a police officer’s cell phone in an attempt to gather sensitive law enforcement information". In 2011 Lisa Harnum was thrown from the 15th floor balcony of her Sydney apartment by her boyfriend Simon Gittany after he learned of her plan to leave him from text messages he intercepted using "MobiStealth", a mobile surveillance app.

These are some of the cases that have made the news, but with hundreds of thousands of customers purchasing these apps from dozens of companies there must be much that is going undetected or unreported.

This repo is a place to keep the results of my analysis of various types of Android stalkerware.

This research is a result of my personal revulsion at the industry that has formed around enabling people to spy on their spouses, their children and their co-workers, profiting off of some of the worst, most paranoid impulses that humans can have is morally reprehensible and in many instances a violation of the law.

My interest in researching stalkerware began last year, after a talk at my local DC44131 meet up by Dan Nash, you can find his talk on stalkerware at BSides Belfast here.

I currently have no plans to expand into iPhone stalkerware analysis, however almost all of the companies featured here offer iPhone versions of their software which most likely operate in a similar fashion in regards to transmission of data, etc.

As I gather more data repo this will be updated regularly.

If you are a researcher or journalist who wants to write about this subject and you think I can be of assistance please get in touch either via nscrutables@protonmail.com or through my Twitter, DMs are open.

In undertaking this research I have become really painfully aware of the genuine ethical issues that accompany investigating this subject. Victims of stalkerware have already been harmed by the installation of the software, probably by someone close to them, and the invasion of their privacy, their intimate moments have been recorded and shared without their knowledge. It is important that in trying to combat this threat we do not inadvertantly make it worse.

As these apps are designed to collect every scrap of information from devices, from Facebook to contacts, URLs visited and photos taken, leaks are almost uniquely damaging for victims.

Examining data leaks for this research I have stumbled across screenshots of phone calls to child protective services, private family photos, WhatsApp chats and fine location GPS data that enabled me to see people's precise home addresses. The incredibly personal nature of this data is what makes stalkerware so insidious and also what makes researching it a balancing act.

If you decide to post data from your findings be aware of the need to consider the wellbeing and privacy of the victims and also be very wary of posting code that might enable other people to easily replicate these services. The apks themselves are obviously already out there, but the back ends to these sites are potentially dangerous in the wrong hands.

A paper that helped solidify and frame the questions I found myself asking is Ethical issues in research using datasets of illicit origin, recommended reading.

As we become more and more dependent on smartphones in our everyday existence they become a vast and oftentimes exhaustive repository of information about us and our lives that are a tempting target for governments and unscrupulous individuals alike.

The history of stalkerware is in parallel to, and develops along with, the history of smartphones themselves. Back in 2006 The Register noted mobile malware called "Mobispy-A" that "records incoming and outgoing SMS messages as well as call logs for dialed and received calls". As part of it's functionality the "malware sends this data to an account on a server", the author notes that "only the purchaser of the commercial software on which Mobispy-A is based has access to this account, which is in any case limited to monitoring call records of one phone."

'Stalkerware' is the term that has been coined for consumer level malware that is generally targeted at specific people and built to operate covertly on mobile devices to enable the collection and monitoring of victim's communications and data. The word 'stalker' is used because this software is linked to domestic violence, although the providers of the apps themselves will frequently attempt to brand their products as "child safety monitoring" or "employee monitoring" tools. These apps are also sometimes placed under the umbrella term "intimate partner surveillance" or IPS. "The Spyware Used in Intimate Partner Violence" is an excellent paper on the marketing of stalkerware and the efficiency of various methods of detecting it.

Some of these apps also enable the user to send SMS messages from the victim's phone, add logged phone call records to the device's call log, or upload files to the victim's device.

As long ago as 2014 it was reported by NPR that of 70 domestic violence shelters they surveyed, "85 percent of the shelters we surveyed say they're working directly with victims whose abusers tracked them using GPS. Seventy-five percent say they're working with victims whose abusers eavesdropped on their conversation remotely — using hidden mobile apps."

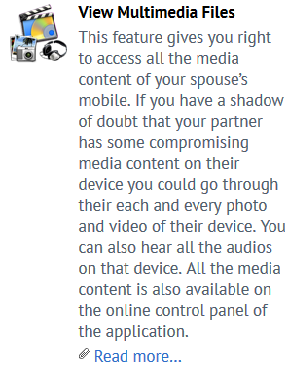

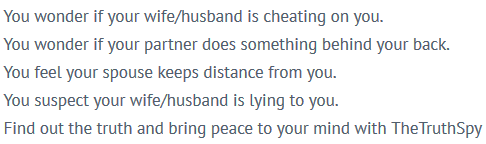

While many of the providers of these apps have modified their marketing techniques, some however, like 'TheTruthSpy' are unrepentantly blatant in their marketing, making no attempt to disguise the sinister purpose of their app.

Marketing for these services often explicitly appeals to paranoid spouses, looking to monetize unhealthy and abusive relationships for financial gain. This, again, from 'TheTruthSpy:

While there has been some media attention focused on this emerging phenomenon, some very well written from motherboard, other sensationalized like below, there has been relatively very little written about stalkerware from a technical perspective.

Breaches of some of the companies that supply this software have helped reveal the scale of the stalkerware issue, they have tens or hundreds of thousands of registered users, each used representing at minimum one infected device.

I see the stalkerware and state sponsored malware industries occupying the same shady ecosystem in a putrid, stagnant backwater of infosec, a small pond in which people with no ethical qualms over arming domestic abusers or abusive dictators with the technological means to victimize people can pretend to be big fish.

I see the stalkerware and state sponsored malware industries occupying the same shady ecosystem in a putrid, stagnant backwater of infosec, a small pond in which people with no ethical qualms over arming domestic abusers or abusive dictators with the technological means to victimize people can pretend to be big fish.

There is actually some evidence to back this up, when stalkerware provider FlexiSpy was hacked a few years ago the resulting leaked data revealed links to Gamma Group, suppliers of state level malware beloved by human rights violators worldwide.

People find these apps via Google ads, despite Google committing to removing adverts that push stalkerware back in 2017, the Play Store and Apple’s App Store but there are also blogs, review sites that make referral commissions and a flourishing scene on YouTube promoting the various apps and their installation.

While most stalkerware companies market directly to consumers through their own websites because of increasing restrictions on what is allowed in the Play Store there are some companies that have found a middle ground between enabling features that could aid in stalking and following Google's rules. The apps that these companies develop and distribute through the Play Store can thus be called 'dual use', they have potential legitimate and legal uses but are also attractive to people wanting to use them to enable illegal surveillance of devices.

Primarily what seems to distinguish these apps from their less legal counterparts, at least in the eyes of Google, is that they do not enable the concealment of the app and its icon from the list of running processes.

Two examples of these kinds of apps are 'Trackview' and 'Track My Phone Pro', both are available in the official Play Store and both support features that make them in many ways indistinguishable from apps that market themselves to paranoid spouses.

'Track My Phone Pro' states that "you can get the location of your mobile, make siren play loud, send a message to your mobile, call a number, enable or disable mobile data, make it vibrate for 5 sec, and even take pic remotely and email pics to your email ID. All this you can do even when your mobile is not with you." From the Play Store page for Trackview the developers describe how the software "turns your smartphones, tablets and PCs into a connected IP camera with GPS locator, event detection, alert and cloud/route recording capabilities".

In the case of 'Track My Phone Pro' the app's developer attaches this statement to the Play Store page.

However the comments for the app show that many users are under no illusion as to how the app can be used.

I've done some form of analysis, primarily using MARA Framework, DroidBox and MobSF, of over three dozen variants of Android stalkerware to date.

Regardless of who is behind the various stalkerware apps, there are some similarities in these apps across the board.

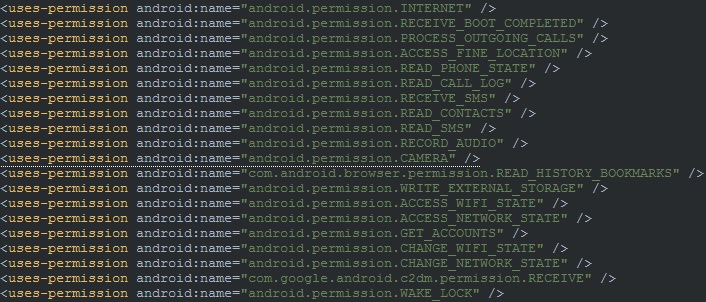

These apps all require that the person installing them has physical access to the phone to be infected, and the ability to unlock that phone for the purposes of installing the app. These apps all carry with them similar requests for permissions in their AndroidManifest files, the file within the app that among other things defines permissions that the app needs in order to access protected parts of the system or other apps.

You can see an example from 'TheTruthSpy' here, most every other stalkerware variant requests much the same permissions.

Most of that is self explanatory, 'GET_ACCOUNTS' allows access to the list of accounts registered to the phone's owner, 'CAMERA' enables the app to covertly take photos or video. 'RECORD_AUDIO' enables eavesdropping (the resulting video and audio files are uploaded to streaming services run by the stalkerware provider in some cases), 'ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION' is particularly worrying in that it enables the app installer to access very precise location data from the victim's phone.

I have mapped GPS data from 250 infected devices taken from a leaked stalkerware provider database here, to give some idea of the global scope of the issue, this is a screenshot as the actual data allowed for pinpointing location down to addresses.

Across the board, almost every stalkerware provider uses a mixture of legitimate infrastructure and their own sort of homebrew framework for exfiltrating data from victim's devices, hosted on their own servers.

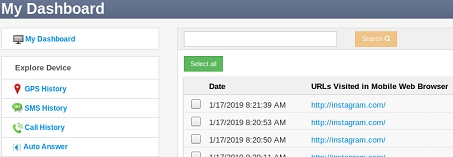

Devices transmit data back to various scripts running on a special domain, subdomain or the app's main site, these scripts pass the data to a database which stores the victim's information and makes it available to the stalker via a web (or sometimes app based) dashboard.

Devices transmit data back to various scripts running on a special domain, subdomain or the app's main site, these scripts pass the data to a database which stores the victim's information and makes it available to the stalker via a web (or sometimes app based) dashboard.

Most of these apps are unable to get, or keep, a place in Google's Play Store because they fail Google's basic requirements for security and privacy, so they must rely on hosting their own apps (and as shown below require that users make changes to device's settings to enable them to work). Many of them avail themselves of services like Crashlytics, Firebase and lesser known equivalents however.

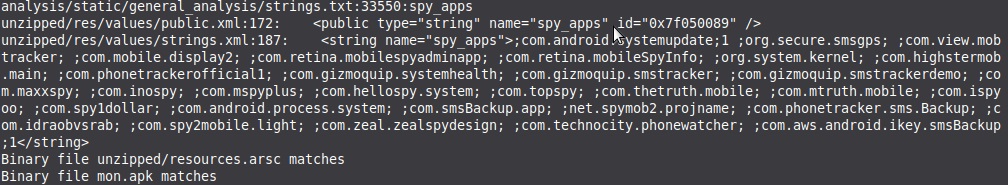

Curiosly only one stalkerware app that I have come across so far adds the functionality of checking for other installed surveillance software as part of its installation procedures. This is "Spy Phone App", developed by Monapp Calabs Limited and Andrei Ciuca, the company's director, operating out of Cyprus.

Almost all of these various services use 'Secure Android ID' as an identifier for victim's devices, it is a 64-bit number that is generated randomly when the Android device is first booted. Stalkerware services render this 64-bit ID number as a 16 character hex string, as seen here.

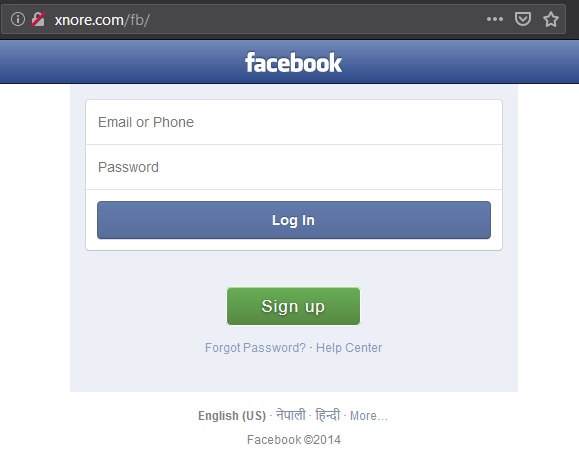

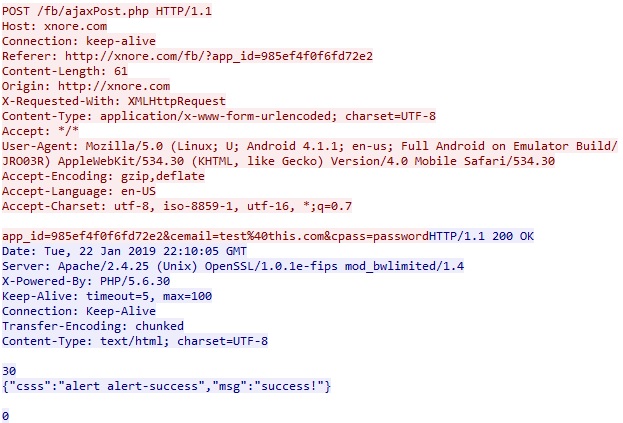

While they use some legitimate services to provide complex infrastructure these providers still must often resort to what would usually be considered straight up traditional malware techniques, for instance 'Xnore' hosts a Facebook phishing login which redirects Facebook traffic from a victim's device and then relays the login and password to whoever installed the stalkerware.

As you can see this phishing page is not SSL secured, this is another feature of many of these apps, while whoever installed the stalkerware can access victim data through a secure web portal, the victim's data is transmitted unencrypted, as seen in this wireshark screen shot.

It is important to note that this lack of basic security demonstrates the lack of care taken with victim's data, however switching to encrypted methods of transferring this data would not make these products any less disgusting and unethical.

These apps generally rely on outdated and insecure methods of obscuring or encrypting data, Base64 encoding, MD5 encryption and when SSL is used certificate pinning to thwart MiTM attacks is generally not implemented.

Insecurity isn't just a feature of the methods these apps use to transfer data, these companies themselves are frequently hacked, their data subsequently leaked after breaches.

'Retina-X' shut down completely after two breaches, 'Mobistealth' and 'Spy Master Pro' were both hacked by an anonymous individual, with data leaked, as mentioned before 'FlexiSpy' was hacked and leaked, 'Xnore' had a breach of customer data because of a website configuration error, the list goes on and on.

I want to take this opportunity to remind anyone reading this thinking about using this software, if you use these services you risk the discovery of your actions and the communications of the people you are spying upon as these companies are not secure and do not seem to prioritize the security of their users or the victims of their users.

I have my suspicions as to how many of these seemingly different products are in fact created by a much smaller number of companies, either stacking their odds of finding customers by seeming to compete with their own software or to make tracing the flow of cash more difficult.

There is, once again, some evidence to support this, whether in code reuse between apps, different apps using the same webhosting companies, app providers reselling or linking to each other's services and in the data that has been leaked from breaches of stalkerware providers. When 'Retina-X' was hacked and went out of business it was revealed that the company was responsible for the creation and marketing of multiple apps, 'Mobile Spy', 'PhoneSheriff', 'TeenShield', 'NetOrbit' and 'SniperSpy'.

Examining the companies that market these products are a vital part of understanding the problem of stalkerware and combating it. I've managed to locate, with some degree of certainty, companies based in India, Vietnam, UAE, Cyprus, Poland, China and Thailand. These various companies carve up the pool of potential customers through marketing (I suspect targeted Google ads based on location of search), which languages they choose to translate their site into and the associated YouTube videos and other social media outreach that the company does.

At times it is obvious that there is a conscious, public rivalry between some of the developers, at times these rivalries spill over into web content.

What follows is brief summaries of the information I have been able to glean about who is behind various apps, where possible I have linked supporting evidence.

One man owns the company that produces 'MobiiSpy', 'Maxxspy', '1topspy', 'Spytic', 'Hellospy' and 'SpyApp247', aside from loving the word 'spy' he had a serious penchant for promoting his apps using his own name for a while, and registering domains with his personal Gmail account, his name appears to be John Nguyen, and he lives in Vietnam. He uses various company names for account registration purposes, either of domains or Paypal accounts, which include "LIXI CORPORATION", "Minoyou Solution" and "1TopSpy LLC".

'ILF Mobile Apps Corp' is responsible for developing 'Highster Mobile', 'Auto Forward Spy', and 'Easy Spy', amusingly I discovered this because other stalkerware producers have made webpages accusing them of "shady business practices" because although it’s "generally normal for one vendor to have multiple similar applications, the reason why they offer three similar products goes further than just marketing to different audiences" and this is in fact because "their products simply do not work". The reviewer goes on to express indignation at the business practices of 'ILF Mobile Apps Corp' and the fact that their terms of service "grant permission to ILF Mobile Apps Corp. to upload the entire Contact list of the device to which you have installed the software" and that "once Contact list is uploaded you agree and understand that ILF Mobile Apps Corp. does now own this information".

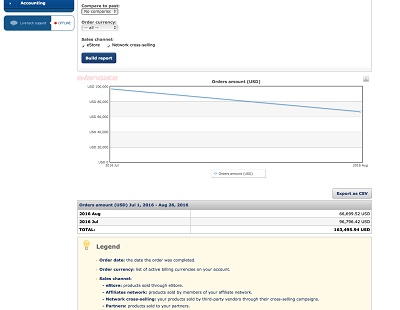

'Spyera' claims to have released the first version of it's stalkerware on April 18th, 2004, the CEO of the company is called Mihat Oger and the company appears to be based in Hong Kong. As far back as 2011 Spyera was included in cautionary articles about stalkerware as in this one from 2011 in which Oger discusses the breakdown of his customers by nation (at the time claiming that 38% were based in the US,c 18% in China) and describing the growth in his company's sales which he says "increased 17 percent from 2009 to 2010 and increased 32 percent from 2010 to 2011". Spyera left a number of documents in browseable directories including these, showing income from sales over the period of a few months and of them downloading one of the apks from the FlexiSpy "flexidie" leak.

In 2016 WtSpy was hacked, their user database of just over 179,000 accounts was leaked and made available for download on the net. Examining this database can provide us with some insight into who their customers were at this time and where we can expect to find this particular app prevalent. WtSpy is, I am fairly certain, based in the United Arab Emirates and markets extensively in Arabic. By comparing the "country_id" field in the leaked database with the source for their registration page we can see which five countries are represented the most in the leak.

| frequency | country_id | country |

|---|---|---|

| 47298 | 196 | Saudi Arabia |

| 13888 | 214 | Syria |

| 12723 | 146 | Morocco |

| 11206 | 1 | Afghanistan |

| 9642 | 244 | Yemen |

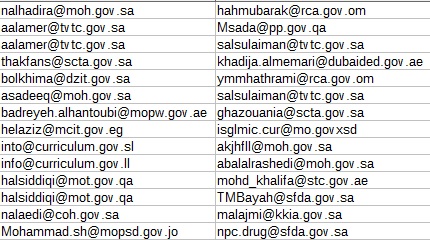

We can see then that the assumptions we could make, based on location and marketing, about the target user base for WtSpy is accurate. Each account represents at least one infected device, so in Saudi Arabia at the time of the database leak there were over 47,000 WtSpy infected devices. Examining the file further we can see that there are a number of .gov addresses among the subscribers, in particular Saudi Arabian government email addresses, with other Middle Eastern countries also making an appearance.

If you have done research relating to stalkerware or have ideas for further research or action on the subject please get in touch with me.

Having thought about this a fair amount I can see three or four ways that stalkerware can be dealt with, minus the involvement of law enforcement or lawyers.

Firstly training, or providing resources, for people who are on the front lines of working with survivors of domestic abuse to pick up on, and handle, signs of stalkerware infections. As I note below a lot of the guides for detecting stalkerware online miss a lot of the obvious tell tale indications, the more informed people in general, and specifically people who have to deal with the direct results of this software, are the better.

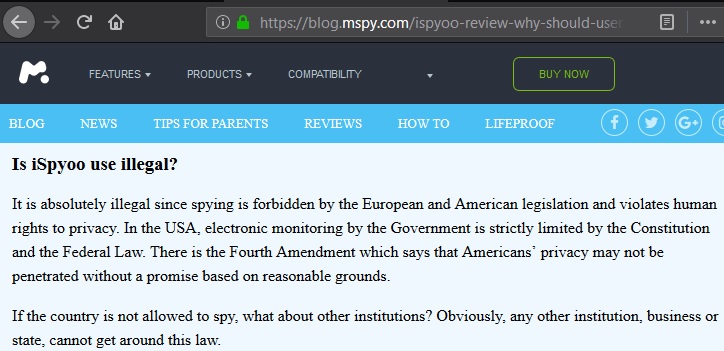

Secondly technical solutions such as ensuring that the various app files are added to virus signature databases and creating network signatures for IDS like Snort. Eva Galperin at the EFF has been working on this as a solution, so far Kaspersky has been willing to take the problem as seriously as it deserves. It is kind of worrying to note that within weeks of this announcement by Kaspersky allegations appeared of them hiring Black Cube to spy on detractors, this is not a good indication of a trustworthy company. To give some background to efficacy of antivirus in general this academic paper discusses the massive gaps in detection that currently exist and shows that even the most successful antivirus solution tested left much to be desired.

It is worth noting that the debate over whether antivirus providers should classify stalkerware as malicious or not has been ongoing for as long as stalkerware has existed, this article from 2006 ("Software Company Argues Product Isn't a Trojan") notes that "F-Secure software recently began blocking a commercial application called FlexiSpy that bills itself as the world's first spy software built for mobile phones". Flexispy responded to this by stating that like "any other monitoring software there may be a possibility for misuse, but there is nothing inherent in FlexiSpy that makes it illegal or malicious" which is the basic talking point that has been used by them and other companies since.

Finally, and this I think can be really very successful from a preventative standpoint, the various companies that produce and market stalkerware do so because it is profitable. To sell their products they need to accept payments somehow and as the various methods of accepting payments come with restrictive terms of service that tend to frown rather heavily on hacking and domestic violence, drawing attention to the imagery and language used to sell stalkerware should result in their accounts being suspended. Many of the people creating and marketing these apps are in countries like Vietnam, China and India, they rely on the essentially untraceable and untaxable flow of dollars that monthly subscriptions to their services bring in, while this cash flows there will always be men willing to fill the demand.

To see just how effective this can be check out this fantastic article from Motherboard, in which the authors question PayPal about their association with 'hellospy'. Cutting off revenue doesn't deal with the underlying problems that fuel the market for these services but it will reduce their appeal for developers as easy money.

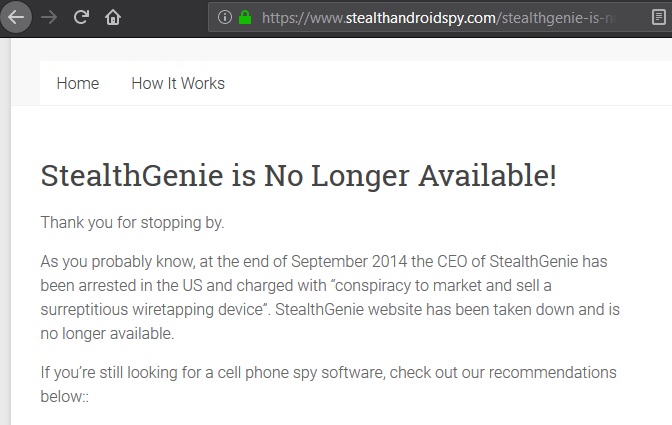

Legal avenues can work too, arrests for selling stalkerware are few and far between but they can be a formidable deterrent.

Many police forces now have access to devices from mobile forensics companies like Cellebrite and Graykey, the marketing from these companies boast of the investigative abilities that this technology will confer upon law enforcement, are they being used to track down stalkerware infections? The resources that many law enforcment agencies have plowed in to forensics hubs for device analysis, are cases of intimate partner surveillance being given any kind of priority?

It is possible to detect these apps, either via the traces they leave on a device or their methods of communicating data back to their command and control servers. From detection it would be relatively simple for law enforcement to enforce a warrant either on PayPal or one of the other payment processors these companies all use or on the web hosting companies or other infrastructure they use which are frequently in Europe or the US, for the purposes of legal jurisdiction.

All that is required is the will to investigate and prosecute.

I've seen a few articles describing simple methods of detecting stalkerware infections on Android phones and they all miss the most obvious method of determining signs of infection, look at the changes to phone settings required by the installation guides of the stalkerware providers themselves.

Every Android stalkerware provider that I have come across so far requires that the person installing the software have physical access to the victim's unlocked phone. If you suspect that someone in your life has access to your phone and might be the kind of person who would install this kind of malicious software that alone is a tip off.

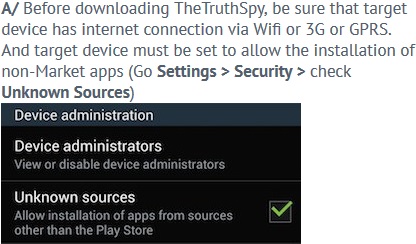

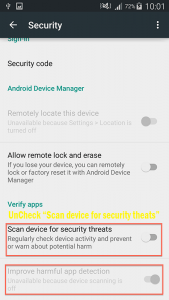

I'm including three screenshots from stalkerware installation made by one of the providers, "TheTruthSpy", to illustrate the changes they require made to victim's phones.

Almost every stalkerware provider I have seen requires that you install their software from their website, they cannot get their product into the Google Play Store. To install apps that are not from the Google Play Store requires changes to the phone's settings, specifically under the settings submenu security the person installing the app has to check the option "Unknown Sources" to allow installation. If you find this option enabled on your phone and you did not enable it, then this again is another serious indication that your phone has been compromised by stalkerware.

Almost every stalkerware provider I have seen requires that you install their software from their website, they cannot get their product into the Google Play Store. To install apps that are not from the Google Play Store requires changes to the phone's settings, specifically under the settings submenu security the person installing the app has to check the option "Unknown Sources" to allow installation. If you find this option enabled on your phone and you did not enable it, then this again is another serious indication that your phone has been compromised by stalkerware.

Secondly, Android 5.0 and above has "Google Play Protect", this is a service that runs on your phone and monitors it for potential threats, this service will interfere with the installation of stalkerware and therefore will be disabled by whoever is loading this software on to your phone. You can find this under your phone's settings security submenu, if it is disabled then this is a clear sign that something is not right with your phone.

Secondly, Android 5.0 and above has "Google Play Protect", this is a service that runs on your phone and monitors it for potential threats, this service will interfere with the installation of stalkerware and therefore will be disabled by whoever is loading this software on to your phone. You can find this under your phone's settings security submenu, if it is disabled then this is a clear sign that something is not right with your phone.

Lastly many of the stalkerware apps require device administrator access, this enables the app to more fully monitor data on your phone. You can check which apps have device administrator access by accessing your security settings and checking "Device Administrators" or sometimes "Phone Administrators", this will provide you with a list of apps with this access.  Bear in mind that stalkerware companies will frequently name their software services with innocuous sounding names like "system.service" or "WiFiService".

Bear in mind that stalkerware companies will frequently name their software services with innocuous sounding names like "system.service" or "WiFiService".

If you are in any doubt I would suggest installing one of the various Android antivirus products and performing a full scan of your phone.

- The Spyware Used in Intimate Partner Violence(2018)

- Motherboard - Domestic Surveillance(2018)

- Undone by his own spying operation, arrest of drug lord shows how surveillance is used to perpetuate gender-based violence

- Commercial Spyware - Detecting the Undetectable (2015)

- Spy vs. Spy: Examining spyware on mobile devices(2012)