[Note to self: break all projects into separated repositories linked by this README. Use them as items in your portfolio. Deploy them using Vercel or directly into your website as subdomains.]

This is the course "React - The Complete Guide" by Maximilian Schwarzmüller, and this is: Things that I didn't know before enrolling this course

Important note: this project uses Yarn instead of NPM.

[a, b] = ["Hello", "Max"];

console.log(a); // Hello

console.log(b); // Max{ name } = { name: "Max", age: 28 };

console.log(name); // Max

console.log(age); // undefined- Thing that I already knew but have forgotten: "JSX" stands for "JavaScript XML"

- Thing that I didn't know: it's because HTML in the end is XML. Mind blowing!

- According to Maximilian, importing React fro 'react' is an archaic practice.

- Every React element, under the hood, is actually a

React.createElement()function/method. It takes 3 arguments:- a string with the name of the object

- an object containing attributes to configure the element

- an infinite that represents elements inside the div tag

return (

<div>

<h2>Let's get started</h2>

<Expenses items={expenses} />

</div>

);

return React.createElement(

"div",

{},

React.createElement("h2", {}, "Let's get started"),

React.createElement(Expenses, { items: expenses })

);- When using a

handleClickinside anonClick={}prop, the reason why you should point to the function (e.g.handleClick) instead of calling it (e.g.handleClick()) is because its nature of being called only when there's a click, not in runtime. If you call the function, React will run it whenever the components is rendered. - React is all about functions. Its rendering procedure is to call

<App />, that calls its children, that call their children, and so on, until everything is rendered all at once. It's a stateless way of displaying HTML. - By using state, React offers us a way to re-render something whenever some data changes. States makes React aware of changes dynamically. That's what it means to be declarative instead of just imperative.

- When you use the function provided by

setState()s destructured array, it will trigger a re-render in the component where you set the data update.

- Sometimes, when you update a huge amount of data at the same time, like in a form for example, you can see yourself relying on a copy of your previous state that is already outdated. To solve this, you should use this syntax instead:

// Old one:

setUserInput({

...userInput,

enteredDate: value,

});// New one:

setUserInput((prevState) => {

return {

...prevState,

enteredDate: value,

};

});This method assures that you're using the last state snapshot instead of the last object created as a copy of the last updated state.

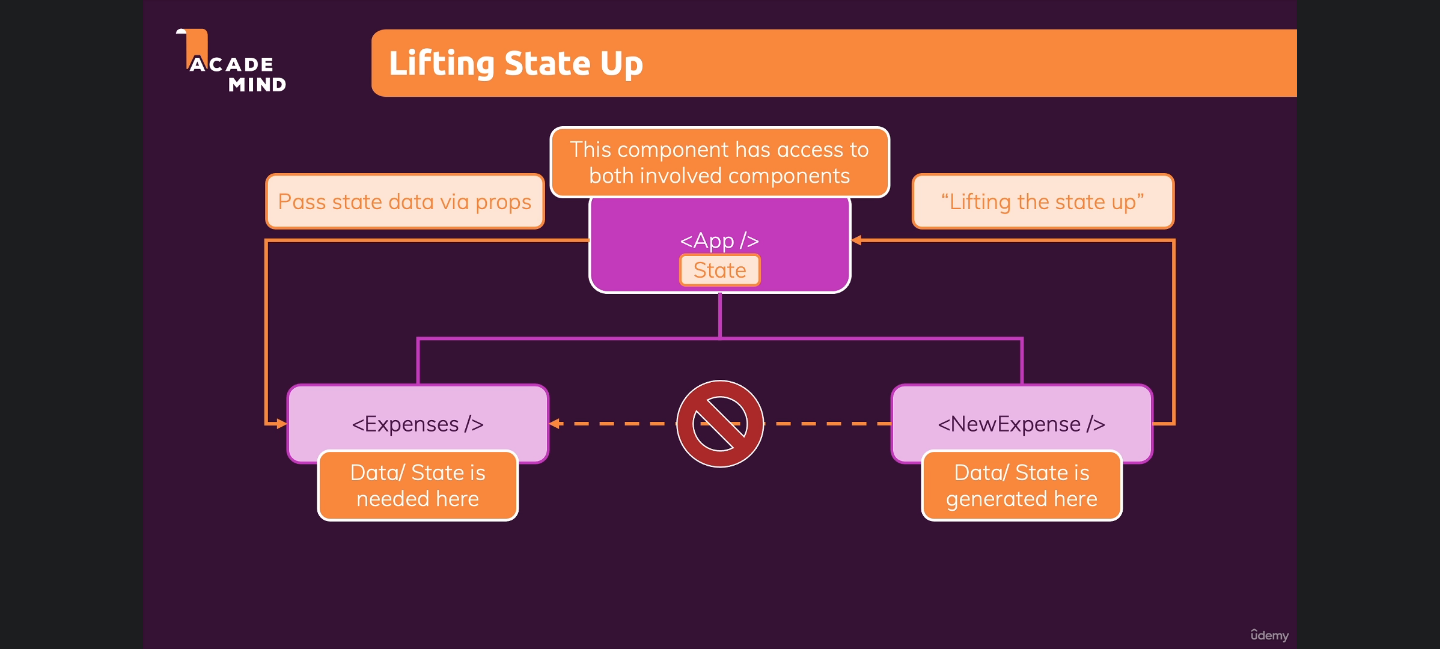

If you declare a function in the parent, pass it as a prop to the child and make the child call it, you can receive data generated in the child as a parameter, and then use it in the parent. I really didn't know that pattern.

The process is rather simple: it's passing data from a component to its sibling by finding their first common parent, which will receive the data and pass it down to its other child (the target one).

A different way to render conditional content: you can put all the rendering logic of mapped list into a let variable with a default value that can be updated it a certain condition is met. Then you render the variable that stores the HTML and its logic instead of calculating everything in the return of the function. Like this:

let expensesContent = (

<div>

<p1>No Expenses Found</p1>

</div>

);

if (filteredExpenses.length > 0) {

expensesContent = filteredExpenses.map((expense) => (

<ExpenseItem

key={expense.id}

title={expense.title}

amount={expense.amount}

date={expense.date}

/>

));

}

return (

<Card className="expenses">

<ExpensesFilter

selected={filteredYear}

onChangeFilter={filterChangeHandler}

/>

{expensesContent}

</Card>

);É possível passar props para dentro dos components criados com o styled simplesmente passando elas como num componente normal.

& input {

display: block;

width: 100%;

border: 1px solid ${(props) => (props.invalid ? "red" : "#ccc")};

background: ${(props) => (props.invalid ? "salmon" : "transparent")}

font: inherit;

line-height: 1.5rem;

padding: 0 0.25rem;

}

& input:focus {

outline: none;

background: #fad0ec;

border-color: #8b005d;

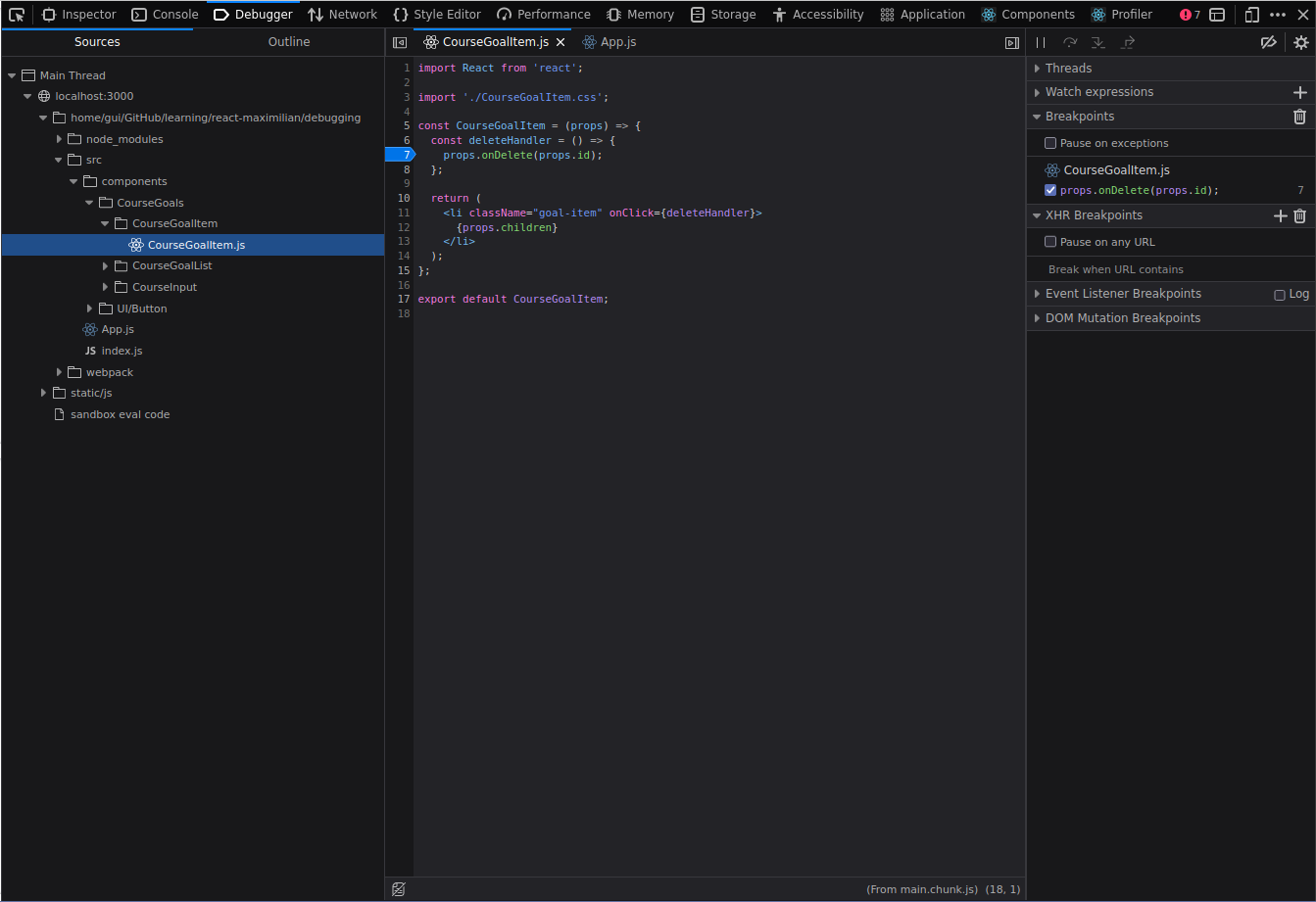

}Just breakpoints 101 here, even though even this knowledge is brand new to me. You can use open Debugging tab, navigate through Sources until you find the problematic file, and line, and then add a breakpoint to start pausing on every function call. Very helpful.

When dealing with the lack of an unique parent component for many children rendered side-by-side, you can use the <Fragment /> as well as arrays:

return [

error && <ErrorModal />, // <-- the comma for each child

<Card>

<p>Content</p>

</Card>

]But this method has a gotcha. It lacks the key prop. But you'll have to hardcode it.

Semantically, modals should not be nested. Since it's an overlay, it should be above anything. It's like creating a button by setting a <div /> with an onclick={} prop. It works, but it's wrong.

So we use Portals to transfer components to somewhere else in the real DOM using an id in the real DOM ('/public/index.html') and ReactDOM.createPortal() in the component we want to move. The first createPortal parameter is the component to be transfered, and second is the reference to the id we set:

{ReactDOM.createPortal(

<Backdrop onConfirm={props.onConfirm} />,

document.getElementById("backdrop-root")

)}We can use refs instead of states to gather input values. But, since refs point to the actual DOM (instead of the Virtual DOM generated by React itself), manipulating them is not-recommended.

When you assign the useRef() to a const, you can use the ref prop to listen to it. It generates an object with a current property in it. Then you can, for example, use exampleRef.current.value to store values typed by the user.

When you access values through refs, you are dealing with Uncontrolled Components. Their internal state is not controlled by React anymore, have this in mind. It's a side-effect of using less code to access the DOM directly through this hook.

The useEffect() hook has 2 parameters, a function, and an Array. The function is executed after every component evaluation if the specified dependency (in the array, the second parameter) changes. That means that useEffect() hook doesn't re-run whenever the component re-renders, it has its own lifecycle.

Note: when you update a state within useEffect(), it triggers an infinite loop because both useEffect() and setState() causes the component to run again. Explaining each step:

-

The component is rendered, so

-

The

useEffect()runs because that's what it does -

If there's a state update inside that

useEffect(), then -

The updating state will make the component to re-render

-

And here's the infinite loop: if the component re-renders, it triggers the step (2):

useEffect()runs, causing the state to be updated again... and so on.

The useEffect(), as its name says, deals with side-effects. They often are HTTP requests, but they can also be, for example, keystrokes in a form your application is listening to.

useEffect is capable of returning either an anonymous/arrow or a named function.

This feature is useful when you need to run something after the main logic within the useEffect() runs.

In the example, we set a timer to update the state that listens to the keystrokes only after the user stopped typing for 500ms. This is what happens: the function that sets the state will be updated only from time to time. But we still need to make it run the state update to record groups of characters typed, not only delaying them.

In this case we use the return of the useEffect() to clear the timeout after every useEffect() trigger. It the user starts typing before the time set in the setTimeout(), it will reset the time interval. By doing this, the state will register only bunches of characters at a time.

useEffect(() => {

const identifier = setTimeout(() => {

setFormIsValid(

enteredEmail.includes("@") && enteredPassword.trim().length > 6

);

}, 500);

return () => {

clearTimeout(identifier);

};

}, [enteredEmail, enteredPassword]);Is a tool when you need more powerful state management.

// the good old useState() syntax:

const [state, updateStateFn] = useState(argument);

// the main useReducer() syntax:

const [state, dispatchFn] = useReducer(reducerFn, initialState, initFn);It seems like the useState() function we already know, since inside the array that function returns there's a state snapshot and a function that updates it. But there's a key difference in this dispatchFn function: it dispatches an action that will be consumed by the first useReducer() argument, reducerFn. It holds both the last state snapshot and the action passed to it, and returns a new, updated state.

Kinda tricky to understand; better seeing it in action (no pun intended!)

Max says we'll know when to use useReducer(). Sure, I'll trust my instincts and starting using in whichever place I see fit. He also says that we use it when useState() becomes too cumbersome.

He couldn't be more generic.

-

The main state management built-in tool

-

Typically we start using it

-

Often is all you need

-

Great for independent pieces of state/data

-

Great if state updates are easy and limited to a few kinds of updates

| useState | useReducer |

|---|---|

| The main state management built-in tool | Great if you need more power |

| Typically we start using it | Should be considered if you have related pieces of state/data |

| Often is all you need | Can be helpful if you have more complex state updates |

| Great for independent pieces of state/data | |

| Great if state updates are easy and limited to a few kinds of updates |

I hate vague/sloppy/generic explanations.

-

Clearly there's a problem whenever you pass a prop to a component just for it to pass the prop downwards to another child component.

-

The other problem related to this practice is the prop drilling, which has to be avoided, even though its definition is kinda loose. You feel when you're practicing prop drilling.

-

Built into React there's a behind-the-scenes, component-wide, State Storage named React Context. It allows us to trigger an action and pass it only to the component interested in it.

-

When creating, for example, a file named

/store/auth-context.js, we use kebab-case instead of CamelCase because it would imply that we're building a component inside it, which is not necessairly true.

-

Good for state management between components' data, but not good to be used in components configuration

-

Not optimized for high frequency changes. There's a better tool for this, namely Redux.

-

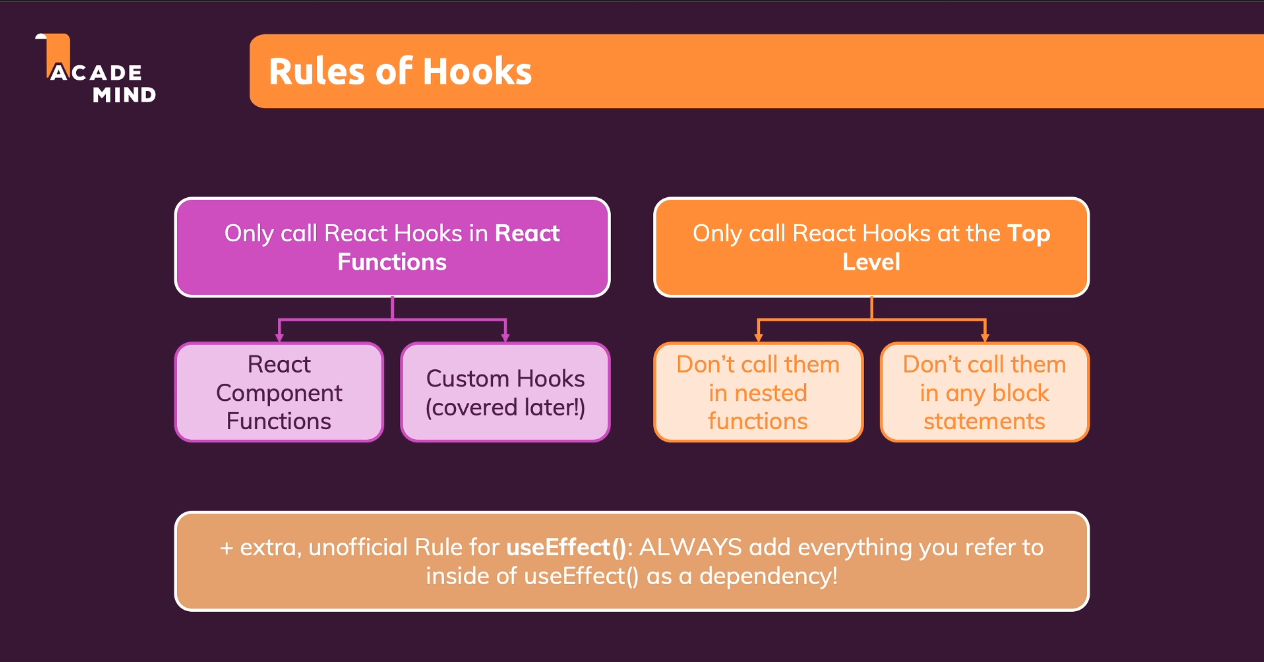

Only call React Hooks in React Functions (React Component Functions or Custom Hooks)

-

Only call React Hooks at the top level.

-

Don't call hooks in nested functions

-

Don't call them in any block statements

-

-

Not official/extra: always add everything you refer to inside

useEffect()as a dependency, unless there's a good reason no to do that.

Max said that it's something you shouldn't be using often because it's not a recommended React pattern; but you should it sometimes. I love when Max explains something the vaguest possible way.

Max then taught how to use an avoidable pattern what involves the useImperativeHandle hook, and refs to focus the password field when the entered password is invalid. Ok, nice, but now I'll need to learn the proper/acceptable way to do that.

A nice trick. When using, for exemple, the <input /> html tag, if you pass a spreaded prop, you can add custom props into an object that will turn into the remainder of accepted props of that tag. To put it simple:

{

id: 0,

type: "text",

}

const Input = (props) => {

return (

<input id={props.input.id} {...props.input} />

)}

<Input input={{

id: "amount",

type: "number",

min: "1",

max: "5",

step: "1",

defaultValue: "1",

} />Note that id is added to that example object, so <input /> stores it as a standard prop. However, type: "text" is an extra prop, which works because of that simple little trick. I've learned something similar when I was studying Python.