- What I Wish I Knew When Learning Picat: Introduction

- Constraint Programming and the Planner

- Constraint and Planner Example Programs

- Constraint Example: Advent of Code 2016 Day 15

- Constraint Example: Jane Street Bug

- Constraint Example: Santa's Knapsack

- The Planner

- Planner Example: Blocks World

- Planner Example: Wizards!

- Planner Example: Moving Stuff

- Planner Example: Twisty Passages All The Same

- Planner Example: Shortest and Longest Path

- Planner and Constraint Example: Traveling Salesperson

- Picat Isn't Python (or Exactly Prolog)

- Maybe You Already Know Prolog?

- Variables

- Assignment (Binding) vs. Unification (Bind or Fail) vs. Equality (Only Numbers)

- Global Maps

- Program Structure and Control Flow

- The

mainpredicate and Picat file extension. - Whitespace

- Anonymous Variables:

_aka underscore - Predicates and Logic Programming "Weirdness":

append/3 append/4for parsing- Functions!

- Is it a Predicates or a Function?

=>vs=and conditions- Pattern matching and

@ - When to use

$and when not to - Function call syntax:

()and. - Statement delimiters

- Control flow:

ifandforeach - Control flow: the

;aka "or" operator - Control flow:

condandcompare_terms - Control flow:

callandapply - Control flow:

list_to_and

- The

- Example: Global fact = Global state

- Example: Dynamic Dispatch with

applyandcall - More

applyandcall - Non-determinism:

?=>and moretable reducefor functional folds- Helper functions for accumulators

- More Haskell Functions in Picat

- Using Picat For Instruction

- Errors I Always Make and How I Compensate

- Type Errors, Numbers and Characters,

printlnvswriteln - More Type Errors: Lists and Arrays

- List Ranges With []

- And More Type Errors:

""vs''aka Atoms and Strings, Oh My - Predicate vs Function (sort of a type error)

- Unification vs Assignment

- Forgetting a comma or a period (or having an extra one)

- Don't use list indexing with decision/domain variables

- Type Errors, Numbers and Characters,

- Debugging

- Things I Still Don't Fully Understand or Wish Had More Example

- Enhancements I'd Like

- Resources

- Appendix: MD5 in Pure Picat

- Acknowledgements

August 2025

I have long been interested in constraint programming, which has been referred to as the "Holy Grail" of programming where the user states the problem and the computer solves it. https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/242224.242304

While this is far from reality, constraint programming can reduce and scan the search space for NP dynamic programming problems without the user having to explicitly code the backtracking/search algorithm. Examples include: shortest path, knapsack, n-queens, Sudoku and so on.

Picat is a great language for learning these concepts and also an interesting general purpose programming language.

My background in programming is mostly procedural (Python) and pure functional (Haskell). So my challenge with Picat is multi-faceted: 1. Learn how constraint programming works in general, 2. Learn how constraint programming works in Picat, 3. Learn how Picat works.

Because Picat is a descendent of Prolog, its core is a logic programming paradigm. And while the Picat manual is excellent, it moves along a quick clip and I had to read it very carefully to understand what I didn't understand. Think Calculus textbook. It's all documented, but makes sense sometimes only after you've learned it.

Also, because it's a niche language, there's a limited amount of online support. There's no StackExchange/Picat. (There are a few Picat questions there though!) I was lucky to get in contact with one of the key developers/users of the language, Håkan Kjellerstrand, who kindly helped me through many a head scratching moment. His website is invaluable: https://hakank.org/picat/.

He also made a customized ChatGPT with Picat's documentation that has helped me as well, although like all LLMs, it can hallucinate solutions that don't work and has a tiny training dataset compared with JavaScript. But it has been more useful than not as I bang my head against the wall of knowledge.

This document is my attempt to share what I learned and is intended for programmers who have similar experience to me: a reasonable grasp of a common language such as Python, C, JavaScript, etc. or a background with a functional language such as Haskell or OCaml, but not much use of Prolog or other logic programming language, and possibly no idea what constraint programming is.

Consider this a rough draft representing my personal learning curve. This document is not intended to be read top to bottom, but rather to help you if you get stuck where I did and hopefully give you the insight to move forward. As such, there's some redundancy between sections because I'm trying to make them self-contained as much as possible.

Notes:

I am much indebted to Advent of Code for providing a wealth of puzzles that have helped me learn Picat (and other languages).

Title inspired by What I Wish I Knew When I was Learning Haskell, which helped me learn that language.

Many extra thanks to Håkan Kjellerstrand for editing a draft of this document, and always being ready to answer any question on Picat.

Remember simultaneous linear equations? For example, here's a problem from Reddit's Learn Math:

$$

x + y = 2 \

y + z = 7 \

z + w = 13 \

w + x = 8 \

w \ge 0 \

x \ge 0 \

$$

Think how you might solve this with any programming languages you know. Maybe nested for loops over possible values? Or a filter with conditions? Or just do it in your head?

With Picat, this is straightforward:

import cp. % the constraint solver module

main =>

X + Y #= 2, % #= means RHS equals LHS in valid solutions

Y + Z #= 7,

Z + W #= 13,

W + X #= 8,

W #>= 0, X #>= 0,

Sols = solve_all([W,X,Y,Z]), % find all solutions

foreach (S in Sols)

[W1,X1,Y1,Z1] = S, % pattern match on the variables

println([w=W1,x=X1,y=Y1,z=Z1]) % print them out

end.

This outputs:

[w = 0,x = 8,y = -6,z = 13]

[w = 1,x = 7,y = -5,z = 12]

[w = 2,x = 6,y = -4,z = 11]

[w = 3,x = 5,y = -3,z = 10]

[w = 4,x = 4,y = -2,z = 9]

[w = 5,x = 3,y = -1,z = 8]

[w = 6,x = 2,y = 0,z = 7]

[w = 7,x = 1,y = 1,z = 6]

[w = 8,x = 0,y = 2,z = 5]

Nice!

My interest in optimization goes back to when I worked on the Optimization Subroutine Library at IBM Kingston in my first job out of college in 1989. IBM needed a technical writer for the manual who had a background in computing and math, and as a dual CS/Math major with a writing minor, who also happened to have a father who worked at IBM for 30 years, I was the perfect person.

OSL was a cutting edge Simplex and interior-point barrier method linear optimization library of subroutines for IBM mainframes that worked with FORTRAN, APL, and hard-core 360 Assembly. It could also take advantage of the "vector processing facility" to do multiple operations simultaneously. Today we call that SIMD.

This was software that cost in the hundreds of thousands of dollars and ran on machines that cost millions. But it was in great demand nonetheless: Airlines and trucking companies used OSL for scheduling, oil and gas companies for evaluating the potential of drill sites.

Nowadays, you can just download for free any of a number of linear programming libraries and run them on your laptop with more compute than any 1990s mainframe.

However, at the time, and still today, the math at the center of this is over my head, and I never really understood how the optimization worked or how to use it myself. Which is why I find Picat so appealing. Picat enables learning about constraint programming and optimization with the linear algebra and discrete mathematics quietly in the background.

Fun fact: A couple the researchers from IBM who wrote much of OSL, John Forrest and John Tomlin, were and are instrumental in COIN-OR, an open source optimization software initiative. John Forrest was not the friendliest to a young technical writer, but John Tomlin was as kind as possible. https://www.informs.org/Recognizing-Excellence/Award-Recipients/John-Forrest https://www.coin-or.org/coinCup/coinCup2007Winner.html

I learned programming on a Radio Shack Color Computer in 1972 and then the first IBM PC a few years later. BASIC and then Pascal were the only languages I had for many years. In those days, before the Internet, any other language, even assembly, were hundreds of dollars (thousands in today's money) and essentially unobtainium.

Pascal was an option because of Borland's $49.99 Turbo Pascal. And so when Borland released a similarly priced Turbo Prolog, I was all in. I attempted to write an Othello program as my project for a CS class in college. And, apologies to Prof. Barry Burd, I got exactly nowhere. With no Stack Overflow or ChatGPT, I was unable to even figure out how to set up the data structure for the board.

So logic programming is also a long time foe I have been wanting to win at least one or two rounds with.

Note: I have since managed to write a version of Othello in Haskell. But not yet Prolog or Picat.

Note: APL is another monster from those days. For now though, it remains left to sleep.

This document has the following primary sections:

- Introduction. (you are here!), which includes some high level information about Picat.

- Constraint and Planner Programming, these capabilities are the reason I wanted to learn Picat and are a central strength of the language. If you are familiar with Prolog then start here.

- Picat is not Python. This is the section if you're unfamiliar with Prolog and logic programming concepts. I had always struggled with these, so I share what I found challenging and helpful. There are also some neat tricks here such as dynamic dispatch.

- Resources. Links to more information about Picat and example code.

- Appendix: Using Picat In Class. Some ideas for how to autograde Picat student assignments.

- Appendix: My Errors. The things I always get wrong, although I'm doing it less now that I've written this!

- Appendix: Debugging. Some ideas for debugging that I rely on.

- Appendix: Stuff I Don't Know. Things that I don't fully understand about Picat.

What is Picat?

- A dynamically typed hybrid of imperative, logic, functional and constraint programming.

- A programming language with support for Boolean Satisfiability (SAT), Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP), Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT), and Finite Domain (FD) Constraint Programming (CP) solvers.

- Combines some of the best ideas of Prolog, Python, Haskell, MiniZinc/z3, OR-Tools.

- A wonderful resource for learning logic and constraint programming.

Answer: all of the above.

Let's look at how Picat stacks up against some programming languages you may know.

| Other Language | Picat |

|---|---|

| Imperative: Python, JavaScript | = Straightforward syntax = Print from any statement to debug - Libraries are limited - Community is small |

| Functional: Haskell, OCaml | = Functional concepts - No lambdas |

| Solvers: Z3, MiniZinc | + Full programming language vs. just a solver |

| Logic: Prolog | + Functions = Unification, non-determinism, tabling = Most "standard" Prolog features |

+ Advantage, = Similar, - Disadvantage

| Concept | Picat |

|---|---|

| Comments | `% percent sign for comments. /* */ for block comments |

| Variables | A=5, B=3.4, C=(1234 mod 7). Note: Variables start with a capital letter in Picat. |

| Numeric Separator | A=1_000_000. This is syntactic sugar. |

| Strings | println("Hello World.") |

| Linked Lists | MyList =[3,4,6,1,56,123.65,"a string?",[a,sub,list]] |

| Arrays (O(1) access) | My2DArray = {{1,2},{3,4}}, println(My2dArray[1,2]). |

| List Comprehension. | Xs = [X : X in 1..5, X != 2]. |

| Pattern Matching | head([H|T])=H. |

| Loops | foreach (X in MyList) Y=X*X,println(X) end. |

| Recursion | fib(0)=1. fib(1)=1. fib(N)=fib(N-1)+fib(N-2).. member(X,[X |

| Functions | myfunc(X) = R => if X>0 then R=X*X else R=X*X*X end. |

| Output | print(), println(), printf() |

| Input | read_file_lines("datafile.txt"). |

| Higher Order Functions | map(reverse,MyStringList). or MyStringList.map(reverse). |

Also: Hashmaps, Sets, Ordered Sets and Binary Heaps.

- Variables start with a Capital Letter.

- Atoms

- Unification

- Finite Domain Variables

- Tabling (Automatic Memoization)

- Non-Determinism

- Definite Clause Grammar (DCG) (Although I don't know how to use them. So if you do, please let me know.)

-

Planner

There is a planner definition language, PDDL, but it is not a general programming language like Picat, and I did not find it very easy to learn.

-

Solver polymorphism + Turing Complete

There are DSL languages such as MiniZinc are designed to work with multiple backend solvers. Also, languages such as Prolog, Python, Java, C++, etc. are Turing Complete with library bindings to solvers, from-the-bottom-up integrated nature of Picat's solvers, the planner module, while being a full programming language does stand out from the crowd.

- Classes, Objects

- Lambdas/Anonymous Functions

- Strong Typing, Type Hinting

- Monads

More at: https://picat-lang.org/download/picat_compared_to_prolog_haskell_python.html

https://picat-lang.org/download/picat_guide.pdf

- The manual is the single most important document for learning Picat. It has everything, but can be very terse, and so must be read closely.

- The index at the back lists all the commands and hyperlinks to them. I use this more than any other method when programming in Picat.

Each clause in Picat ends with a .. In example code each line is fully distinct for variable scope. % begins a comment.

For example:

A=5. % A=5.

But A is only 5 in this clause. After the ., A goes out of scope.

And if you prefer spaces around your operators, please go ahead.

A="A Wildebeest!". % A is a string.

Again, A is in scope only until the . and doesn't exist after.

B=A+A. %** Error : Free variable in expression: '+'

A hasn't been defined in this clause.

But using a , provides a continuous scope for A.

A=5,B=A+A. %A=5 and B=10.

In Prolog and Picat, it's common to refer to a function by the number of arguments it has. This is known as the functions' arity. For example, new_list/1 as in:

A=new_list(5). % make a list of 5 things

Why? Because often there's a version of the predicate or function with a different number of arguments.

A=new_list(5,0). % make a list of 5 things and initialize them all to 0.

Constraint programming lets you solve problems that require searching through possible solutions. How can you place queens on a chessboard so that no queen is able to take another? (N-queens) Can a knight on chessboard visit every square once and end by returning to its starting square? (Knights tour) The best route for a traveling salesman? (Traveling Salesman) The quickest way out of a maze? (Shortest Path) How best to choose items to fill a suitcase? (Knapsack) How to complete a partially filled Sudoku puzzle? (Sudoku)

All of these, and many many more can be found via the links in the resources section.

The main concept here is the satisfaction and sometimes optimization of a function defined by a set of rules aka constraints. The function has variables whose values are not known, but can be defined to be within a given range. These are called "decision variables," and differ from normal variables.

Decision variables can be real/floating point values or integers, and in most cases, there's no closed form solution to obtain their values. Constraint programming is NP-Hard. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integer_programming#Heuristic_methods

There are many applicable techniques you may have seen in a CS algorithms class: Dijkstra's algorithm, A*, recursion/induction, A/B pruning, branch-and-bound, fail first, breadth first search, depth first search, simplex, gradient descent, satisfiability solver, memoization/tabling or just brute force.

A solution using these algorithms is found through iteration and any efficiency over brute force is through careful selection of which potential solution to try next, when to give up and try a different one, and identification of when a given search location is the same as a previous one. This last item is also known as symmetry breaking, that is, if a state is identical/symmetrical to a previous one, don't do the calculations all over again.

These algorithms can reduce the time to find a solution from hours to fractions of a second, but learning all of them and implementing them for a specific problem can be challenging. Enter Picat!

Picat has multiple built-in solvers: Boolean Satisfiability (SAT), Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP), Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT), and Finite Domain (FD) Constraint Programming (CP). Incredibly, the interface to all of them is largely the same. This lets you switch between CP and SAT, for example by just changing and import statement.

There's also the amazing a Planner for finding minimum cost solutions to problems expressed via actions on a global state.

Let's take the example every dynamic programming text begins with, Fibonacci numbers.

fib(0) = 1.

fib(1) = 1.

fib(N) = fib(N-1)+fib(N-2).

Run this and we quickly see a problem with compute time.

main =>

time(println(fib(5))),

time(println(fib(30))),

time(println(fib(40))).

---------------------------------

8 CPU time 0.0 seconds.

1346269 CPU time 0.042 seconds.

165580141 CPU time 4.755 seconds.

---------------------------------

fib is recalculating every value of N-1 and N-2 for each N. At fib(40) that's 331,160,281 recursive calls. https://cboard.cprogramming.com/c-programming/168662-fibonacci-how-long-would-take.html

The solution is to memoize the values into a hash table after they are computed so that they can be looked up rather than brute forced on subsequent calls.

Picat (and many Prolog solutions) make this ridiculously easy. Here's the revised code.

main =>

time(println(fib(5))),

time(println(fib(30))),

time(println(fib(40))),

time(println(fib(4000))).

table

fib(0) = 1.

fib(1) = 1.

fib(N) = fib(N-1)+fib(N-2).

---------------------------------

8 CPU time 0.0 seconds.

1346269 CPU time 0.0 seconds.

165580141 CPU time 0.0 seconds.

64574884490948173531376949015369595644413900640151342708407577598177210359034088914449477807287241743760741523783818897499227009742183152482019062763550798743704275106856470216307593623057388506776767202069670477506088895294300509291166023947866841763853953813982281703936665369922709095308006821399524780721049955829191407029943622087779296459174012610148659520381170452591141331949336080577141708645783606636081941915217355115810993973945783493983844592749672661361548061615756595818944317619922097369917676974058206341892088144549337974422952140132621568340701016273422727827762726153066303093052982051757444742428033107522419466219655780413101759505231617222578292486081002391218785189299675757766920269402348733644662725774717740924068828300186439425921761082545463164628807702653752619616157324434040342057336683279284098590801501

CPU time 0.013 seconds.

---------------------------------

The core idea of constraint programming are decision variables, which are variables that have a range of potential values that are then solved by adding conditions/constraints they must meet.

Terminology Note: the Picat manual calls these domain variables and the common term of art is decision variable. According to IBM, a decision variable has a domain. So there you go. I will largely use domain because I cut-and-pasted a good bit from the manual.

Here's an example. Note that the module cp must be imported to use domain variables.

import cp. % needed for ::/2

A :: 1..10 % A is a number between 1 and 10

If you type this into the interactive Picat REPL, you get:

A = DV_0104d8_1..10

Let's modify this so that A must be even. We do this by adding a constraint with #=.

A :: 1..10, A mod 2 #= 0.

% REPL says: A = DV_010970_2_4_6_8_10

This shows the power of a constraint solver: Sometimes the domain can be reduced directly, i.e. the domain if A is now only the even numbers. This is discussed more in the Picat Constraint Programming book, chapter 2-3.

It's also easy to make a list or array of domain variables. Here's a contrived problem:

- 5 increasing numbers that differ by 1,2,3, and 4

- The product of the numbers is less than 100000

- The first number is as large as possible Let's say we want to find a sequence of 5 numbers between 1 and 100 where their product is less than 100000, but where the first number is as large as possible (but between 1 and 100).

import cp.

main =>

N :: 1..100,

X = new_list(5),

X :: 1..100,

Y :: 0..100000,

increasing_strict(X), % not really necessary

foreach(I in 1..X.len-1)

X[I+1] #= X[I]+I

end,

X[1] #> N,

prod(X)#<Y,

solve([$max(N)],X ++ [Y]), % find largest N

println(y=Y),

println(x=X),

println(n=N).

Output is :

y = 72577

x = [6,7,9,12,16]

n = 5

There are lots of constraints that can be applied to, via a constraint operator or to a list or expression of domain variables and global constraints.

Picat has implemented quite a few constraints, but there are so, so, so many more. Hakan has implemented more of them here: https://www.hakank.org/picat/#global.

Rabbit Hole: There's even a Global Constraint Catalog! Take a look at your own peril to your free time. And should you want to go down this hole, perhaps try to implement one of these constraints in Picat!

Numeric: ::, notin, #=, #!=, #<, #=<, #<=, #>, #>=

Logical: #~ (not),#/\ (and),#^ (XOR),#\/ (or),#=> (implication, left side implies right),#<=> (equivalence, left and right are equivalent)

cond(BoolConstr,ThenExp,ElseExp): if the Boolean constraint is true, then the ThenExp else ElseExpcount(V,List): The number of times V occurs in a list of variablesmax(List): The maximum a list of domain variablesmax(Exp1,Exp2): The maximum of Exp1 and Exp2min(List): The minimum of a list of domain variablesmin(Exp1,Exp2): The minimum of Exp1 and Exp2prod(List): The product of a list of domain variablessum(List): The sum of a list of domain variables

I often think I need to constrain on the length of a list, but that's because I'm thinking about the problem from my Python/Haskell view. What I really want is usually count or max or sum.

For example, in this Advent of Code problem, I want to minimize the number of items in the list Bins assigned to bin 1. ItemBins[X] = 0 for an assignment of that element to bin 1 and Bins[X] != 0 for any other bin.

My initial thought: Bins should be shortest. Therefore, filter Bins and then minimize len(Bins). But this is me thinking like an imperative or functional programmer. What I really needed was to get the count of items in Bins equal to 0. I could do this a few ways:

L1 #= sum([(Bins[I] #= 0) : I in 1..N]), % L1 = Bin 1 size

L1 #= sum([1 : I in 1..N, Bins[I]] #= 0) % condition on right hand side of list comprehension

L1 #= count(0,Bins)

% and then in when we invoke solve, we use min

solve($[min(L1)],Bins).

I copied this list (and the majority of the text) from the Picat manual, but reduced to the high-level points. This means I removed some detail and for the more complex constraints, refer to the manual! https://picat-lang.org/download/picat_guide.pdf

Note: In all cases where there is a list List it can also be an Array.

-

acyclic(Vs,Es): The undirected graph represented by Vs and Es contains no cycles. [see hcp for how the graph is defined] -

acyclic_d(Vs,Es): The directed graph represented by Vs and Es contains no cycles. -

all_different(List): All variables in the list or array are different. -

all_distinct(List): The same asall_different, but for thecpmodule it maintains a higher level of consistency. For some problems, this is faster, and, for some other problems, it is slower. -

all_different_except_0(List): This constraint is true if all non-zero values in the List are different. -

assignment(List 1,List 2): This constraint ensures that the first List is a dual or the second. i.e., if the ith element of the first is j, then the jth element of the second is i. -

at_least(N,L,V): There are at least N elements in L that are equal to V, all must be integers. -

at_most(N,L,V): There are at most N elements in L that are equal to V, all must be integers. -

circuit(List): The List forms a Hamiltonian cycle. This constraint ensures that each variable has a different value, and that the graph formed by the assignment does not contain any sub-cycles.For example, for the constraint

circuit([X1,X2,X3,X4]),[3,4,2,1]is a solution, but[2,1,4,3]is not, because1->2, 2->1, 3->4, 4->3contains two sub-cycles. -

count(*V,List,Rel,N): The number of elements of List where V Rel N is true. Rel is one of#=,#!=,#>,#>=,#<,#=<, or#<=. This constraint can be defined as:count(V,L,Rel,N) => sum([V #= E : E in L]) #= Count, call(Rel,Count,N). -

count(V,List,N): The same ascount(V,List,#=,N). -

cumulative(Starts,Durations,Resources,Limit): This constraint is for describing and solving time-based scheduling problems. The arguments Starts, Durations, and Resources are lists of integer-domain variables of the same length, and Limit is an integer-domain variable.Let Starts be [S1 , S2 , . . ., Sn ], Durations be [D1 , D2 , . . ., Dn ], and Resources be [R1 , R2 , . . ., Rn ].

For each job i, Si represents the start time, Di represents the duration, and Ri represents the units of Resources needed. Limit is the limit on the units of Resources available at any time. This constraint ensures that the limit cannot be exceeded at any time.

-

decreasing(List): The List is in (non-strictly) decreasing order. -

decreasing_strict(List): The List is in strictly decreasing order. -

diffn(RectangleList): This constraint ensures that no two rectangles in RectangleList overlap with each other. A rectangle in an n-dimensional space is represented by a list of 2 × n elements [X1 , X2 , . . ., Xn , S1 , S2 , . . ., Sn ], where Xi is the starting coordinate of the edge in the ith dimension, and Si is the size of the edge. -

disjunctive_tasks(Tasks): Tasks is a list of terms. Each term has the formdisj_tasks(S1,D1,S2,D2), whereS1andS2are integer-domain variables, andD1andD2are positive integers. This constraint is equivalent to posting the disjunctive constraintS1+D1 #=< S2 #\/ S2+D2 #=< S1for each term inTasks; the constraint converts the disjunctive tasks into global constraints. -

element(I,List,V): The Ith element of List is V, where all are integer-domain variables. -

element0(I,List,V): The same as element(I,List,V), except 0-based, rather than 1-based, indexing is used. -

exactly(N,List,V): This constraint succeeds if there are exactly N elements in L that are equal to V , all must be integer-domain variables. -

global_cardinality(List,Pairs): List is a list of integer-domain variables [X1 , . . ., Xd], and Pairs is a list of pairs [K1 -V1 , . . ., Kn -Vn], where each key Ki is a unique integer, and each Vi is an integer-domain variable.The constraint is true if every element of L*ist is equal to some key, and, for each pair Ki-Vi , exactly Vi elements of List are equal to Ki. This constraint can be defined as follows:

global_cardinality(List,Pairs) => foreach ($Key-V in Pairs) sum([B : E in List, B#<=>(E#=Key)]) #= V end. -

hcp(Vs,Es): The directed graph represented by Vs and Es forms a Hamiltonian cycle.Vs is a list of pairs of the form {V,B}, and Es is a list of triplets of the form {V1,V2,B}.

A pair {V,B} in Vs, where V is a ground term and B is a Boolean variable, denotes that V is in the graph if and only if B = 1.

A triplet {V1,V2,B} denotes that V1 is connected to V2 by an edge in the graph if and only if B = 1.

The

circuitandsubcircuitconstraints can be implemented as follows by usinghcp:

circuit(L) =>

N = len(L),

L :: 1..N,

Vs = [{I,1} : I in 1..N],

Es = [{I,J,B} : I in 1..N,

J in fd_dom(L[I]),

J !== I,

B #<=> L[I] #= J],

hcp(Vs,Es).

subcircuit(L) =>

N = len(L),

L :: 1..N,

Vs = [{I,B} : I in 1..N,

B #<=> L[I] #!= I],

Es = [{I,J,B} : I in 1..N,

J in fd_dom(L[I]),

J !== I,

95B #<=> L[I] #= J],

hcp(Vs,Es).

-

hcp(Vs,Es,K): The same as hcp(Vs,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

hcp_grid(A): This constraint ensures that the grid graph represented by A, which is a two-dimensional array of Boolean (0/1) variables, forms a Hamiltonian cycle.In a grid graph, each cell is directly connected horizontally and vertically, but not diagonally, to its neighbors. Only cells labeled 1 are considered as vertices of the graph. This constraint is implemented as follows by using

hcp:

hcp_grid(A) =>

NRows = len(A),

NCols = len(A[1]),

Vs = [{(R,C), A[R,C]} :

R in 1..NRows,

C in 1..NCols],

Es = [{(R,C), (R1,C1), _} :

R in 1..NRows,

C in 1..NCols,

(R1,C1) in neibs(A,NRows,NCols,R,C)],

hcp(Vs,Es).

neibs(A,NRows,NCols,R,C) =

[(R1,C1) : (R1,C1) in [(R-1,C), (R+1,C),

(R,C-1), (R,C+1)],

R1 >= 1, R1 =< NRows,

C1 >= 1, C1 =< NCols,

A[R1,C1] !== 0].

-

hcp_grid(A,Es): The same ashcp_grid(A), except that it also restricts the edges to Es, which consists of triplets of the form {V1,V2,B}.In a triplet in Es, V1 and V2 take the form (R,C), where R is a row number and C is a column number, and B is a Boolean variable, which denotes that V1 is connected to V2 by an edge in the graph if and only if B = 1. If Es is a variable, then it is bound to the edges of the grid graph.

-

hcp_grid(A,Es,K): The same ashcp_grid(A,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

increasing(List): The List is in (non-strictly) increasing order. -

increasing_strict(List): The List is in strictly increasing order. -

lex_le(List 1,List 2): List 1 is lexicographically less than or equal to List 2. -

lex_lt(L1 ,L2 ): (List 1,List 2): List 1 is lexicographically less than to List 2. -

matrix_element(Matrix,I,J,V): True if the entry at <I,J> in Matrix is V, where all are integer-domain variables. -

matrix_element0(Matrix,I,J,V): The same asmatrix_element, except that it uses 0-based, rather than 1-based, indexing. -

neqs(NeqList): NeqList is a list of inequality constraints of the formX #!= Y, whereXandYare integer-domain variables. This constraint is equivalent to the conjunction of the inequality constraints in NeqList, but it extractsall_distinctconstraints from the inequality constraints -

nvalue(N,List): The number of distinct values in List is N, where List is a list of integer-domain variables. -

path(Vs*,Es,Src,Dest): The undirected graph represented by Vs and Es has a path from Src to Dest. [see hcp for how the graph is defined]Note that the graph is assumed to be undirected. If there exists a triplet {V1,V2,B} in Es, then the triplet {V2,V1,B} will be added to Es if it is not specified.

-

path_d(Vs,Es,Src,Dest): The same aspath(Vs,Es,Src,Dest), except that the graph is directed. -

regular(List,Q,S,M,Q0,F): Given a finite automaton (DFA or NFA) of Q states numbered 1, 2,...,Q with input 1..S, transition matrix M , initial state Q0 (1 ≤ Q0 ≤ Q), and a list of accepting states F, True if the List is accepted by the automaton.The transition matrix M represents a mapping from 1..Q × 1..S to 0..Q, where 0 denotes the error state. For a DFA, every entry in M is an integer, and for an NFA, entries can be a list of integers.

The

regularconstraint is covered in the Constraint book -

scalar_product(A,X,Product): The scalar product of A and X is Product, where A and X are lists or arrays of integer-domain variables, and Product is an integer-domain variable. A and X must have the same length.

• scalar_product(A,X,Rel,Product): The scalar product of A and X has the relation Rel with Product, where Rel is one of the following operators: #=, #!=, #>=, #>,

#=< (or #<=), and #<.

-

scc(Vs,Es):The undirected graph represented by Vs and Es is strongly connected. [see hcp for how the graph is defined]Note that the graph is assumed to be undirected. If there exists a triplet {V1,V2,B} in Es, then the triplet {V2,V1,B} will be added to Es if it is not specified

-

scc(Vs,Es,K): The same asscc(Vs,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

scc_grid(A): This constraint ensures that the grid graph represented by A, which is a two-dimensional array of Boolean variables, forms a strongly connected undirected graph.

In a grid graph, each cell is directly connected horizontally and vertically, but not diagonally, to its neighbors. Only cells labeled 1 are considered as vertices of the graph.

This constraint is implemented as follows by using

scc:

scc_grid(A) =>

NRows = len(A),

NCols = len(A[1]),

Vs = [{(R,C), A[R,C]} :

R in 1..NRows,

C in 1..NCols],

Es = [{(R,C), (R1,C1), _} :

R in 1..NRows,

C in 1..NCols,

(R1,C1) in neibs(A,NRows,NCols,R,C),

(R,C) @< (R1,C1)],

scc(Vs,Es).

neibs(A,NRows,NCols,R,C) =

[(R1,C1) : (R1,C1) in [(R-1,C), (R+1,C),

(R,C-1), (R,C+1)],

R1 >= 1, R1 =< NRows,

C1 >= 1, C1 =< NCols,

A[R1,C1] !== 0].

Note that there is an edge between each pair of neighboring cells in the resulting graph as long as the cells are in the graph.

-

scc_grid(A,K): The same asscc_grid(A,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

scc_d(Vs,Es): The directed graph represented by Vs and Es is strongly connected, where Vs and Es are the same as those in scc(Vs,Es), except that the graph is directed. -

scc_d(Vs,Es,K): The same asscc_d(Vs,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

serialized(Starts,Durations): This constraint describes a set of non-overlapping tasks, where Starts and Durations are lists of integer-domain variables, and the lists have the same length. Let Os be a list of 1s that has the same length as Starts. This constraint is equivalent to cumulative(Starts,Durations,Os,1). -

subcircuit(List): This constraint is the same as circuit(List), except that not all of the vertices are required to be in the circuit. If the ith element of List is i, then the vertex i is not part of the circuit. -

subcircuit_grid(A): The grid graph represented by A, which is a two-dimensional array of Boolean (0/1) variables, forms a Hamiltonian cycle.In a grid graph, each cell is directly connected horizontally and vertically, but not diagonally, to its neighbors. Only non-zero cells are considered as vertices of the graph.

-

subcircuit_grid(A,K): The same assubcircuit_grid(A), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the graph to be K. -

tree(Vs,Es): This constraint ensures that the undirected graph represented by Vs and Es is a tree. [seehcpfor how the graph is defined]Note that the graph to be constructed is assumed to be undirected. If there exists a triplet {V1,V2,B} in Es, then the triplet {V2,V1,B} will be added to Es if it is not specified.

-

tree(Vs,Es,K): The same astree(Vs,Es), except that it also constrains the number of vertices in the tree to be K.

Let's go back to the example I used in the intro. I fibbed a little. Yes, it's easy to solve this toy problem and yes it can be done with all the solvers, but using each solver is slightly different. They aren't fully "hot swappable".

Here's the full version of that code where all the solvers are specified. You can try this by uncommenting a different solver from the one in the code.

% import cp. % solve with cp

% import sat. % solve with sat

% import mip. % solve with mip, you need to install cbc, glpk, gurobi or compile Picat from scratch for scip

import smt. % solve with smt, you need to install cvc or z3

main =>

% for sat and smt, need to explictly make new dvars

% also works for cp and mip,

% but cp can figure out the domain without new_dvar/0

% but if you want non-integer solutions for mip

% need to specify they can be real numbers with something after the decimal point

% for example, instead of new_dvar use W :: 0.0..100.0

W = new_dvar(), % ideally set to a more limited doman

X = new_dvar(), % new_dvar allows for any +/- integer value

Y = new_dvar(), % based on architecture: either 32-bit or 64-bit

Z = new_dvar(),

X + Y #= 2,

Y + Z #= 7,

Z + W #= 13,

W + X #= 8,

W #>= 0, X #>= 0,

Sols = solve_all([W,X,Y,Z]), % cp, sat or smt which defaults to calling z3

% Sols = solve_all($[cbc],[W,X,Y,Z]), % one option for mip

foreach (S in Sols)

[S1,S2,S3,S4] = S,

println([w=S1,x=S2,y=S3,z=S4])

end.

solve(Vars) finds one solution and solve_all = Sols finds, well, all the solutions.

solve is a predicate and the domain variables in Vars will be replaced with a valid solution after the call to solve.

solve_all = Sols is a function and the list of valid solutions is bound to Sols. Sols will be a list even if there's only one solution.

When calling solve and solve_all there are some common options you can select, regardless of which solver you use.

-

$limit(N): Search up to N solutions. -

$max(Var): Maximize the variable Var. -

$min(Var): Minimize the variable Var. -

$report(Call): Execute Call each time a better answer is found while searching for an optimal answer. (Not available withmip.) I used this for debugging in this program.

Options are the first argument in a solve call and have to be inside a list, even if there's only one.

For example, in the above we could write:

Sols = solve_all([$min(W)],[W,X,Y,Z]).

or

Sols = solve_all($[limit(3),report(printf("Got one! %w",W))],[W,X,Y,Z]).

Note the use of $. This means that Picat should not attempt to evaluate the term as an immediate function call. Also note that the $ can be outside of the list for multiple options. Or inside on both options. More on $ here.

Let's look at the four solver modules and what makes them different from each other, and the options you can provide to the solver for them.

Note: Picat is primarily focused on problems with integer aka finite-domain solutions. (Yes, integers are infinite, but not in computer programs that are expected to halt.) MIP provides the ability to have real-valued solutions.

On the other hand, Picat does have a neural network modules that interfaces to the FAAN neural network library. I'm sure someone could use it for non-linear optimization, given that this is exactly what neural networks do. However, that person is not me. Hakan, of course, has some example code.

CP finds feasible values for decision variables by searching through and reducing the domains of those variables via algorithmic techniques such as: breadth and depth-first search, tabling (memoization), backtracking, refinement, perturbation, constraint propagation, combinatorics, unification, and other heuristics.

Note: The cp module has been more than sufficient for all the Advent of Code problems in this text, and it's been the main one I use for constraints. It also has the most options to adjust the search strategy. However, because cp has been so quick, I have not tried the other solvers very much, but that doesn't mean you shouldn't try them.

Also, I have also started to see many Advent of Code days as being aligned to planner because there's such a plethora of shortest path or action-next action problems.

Here's the scoop copied right out of the manual:

-

backward: The list of variables is reversed first. -

constr: Variables are first ordered by the number of attached constraints. -

degree: Variables are first ordered by degree, i.e., the number of connected variables. -

down: Values are assigned to variables from the largest to the smallest. -

ff: The first-fail principle is used: the leftmost variable with the smallest domain is selected. -

ffc: The same as with the two options:ffandconstr. -

ffd: The same as with the two options:ffanddegree. -

forward: Choose variables in the given order, from left to right. -

inout: The variables are reordered in an inside-out fashion. For example, the variable list [X1,X2,X3,X4,X5] is rearranged into the list [X3,X2,X4,X1,X5]. -

label$(CallName)$ : This option informs thecpsolver that once a variable$V$ is selected, the user-defined call$CallName(V)$ is used to label$V$ , where$CallName$ must be defined in the same module, an imported module, or the global module. -

leftmost: The same asforward. -

max: First, select a variable whose domain has the largest upper bound, breaking ties by selecting a variable with the smallest domain. -

min: First, select a variable whose domain has the smallest lower bound, breaking ties by selecting a variable with the smallest domain. -

rand: Both variables and values are randomly selected when labeling. -

rand_var: Variables are randomly selected when labeling. -

rand_val: Values are randomly selected when labeling. -

reverse_split: Bisect the variable’s domain, excluding the lower half first. -

split: Bisect the variable’s domain, excluding the upper half first. -

updown: Values are assigned to variables from the values that are nearest to the middle of the domain.

I say this later on, but it bears repeating: The search and labeling methods can greatly affect solution time. See pgs 59-61 in the Picat constraint book for an example of trying all the combinations of solve options on a Magic Squares problem. Results there range from essentially instantaneous to more than the author's set limit of 10 seconds.

SAT converts a constraint problem into propositional logic via a Boolean algebra expression composed of ands and ors. This representation of the problem with only ^ (and) and v (or) is known as Conjunctive Normal Form or Clause Normal Form (CNF).

SAT solvers rely on an extensive body of computer science research that shows the equivalence of many NP-Hard problems to both each other and to SAT. And that according to the Cook-Levin theorem, "Any problem in NP can be reduced in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine to the Boolean satisfiability problem."

Here's an example of a Sudoku rule that each row has all numbers in CNF from an Aalto University course.

The full example at the link has 6 rules:

The CNF is run through the SAT solver to determine if the there's an assignment of the variables (in the above

Picat manages the conversion of a constraint program and its domain variables into CNF and then runs its internal SAT solver. However, if you want to use your own, you can have Picat save (dump) the CNF file. Here's a link to a bunch of SAT solvers and more tutorials.

Here's Picat's options when using sat:

-

dump: Dump the CNF code to stdout. -

dump$(File)$ : Dump the CNF code to$File$ . -

seq: Use sequential search to find an optimal answer. -

split: Use binary search to find an optimal answer (default). -

$nvars$(NVars)$ : The number of variables in the CNF code is$NVars$ . -

$ncls$(NCls)$ : The number of clauses in the CNF code is$NCls$ .

I believe $nvars and $ncls provides access to the number of variables and clauses should you need them.

SMT are built on the ideas of SAT and include additional methods and data structures such as bitvectors. Many SMT solvers make use of DPLL(T).

Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland (DPLL) algorithm is a complete, backtracking-based search algorithm for deciding the satisfiability of propositional logic formulae in conjunctive normal form, i.e. for solving the CNF-SAT problem. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DPLL_algorithm

SMT solvers are also closely related to automated theorem provers, and one of the main SMT solver, Z3 from Microsoft Research, states on its web page, "A theme shared among many of the algorithms is how they exploit a duality between finding satisfying solutions and finding refutation proofs."

To use the smt module in Picat, you need to install an external SMT solver and invoke solve with the name of the solver. Picat will export a file with the appropriate format and then call the external solver. Picat uses the SMT-LIB2 format for output. SMT options are:

| SMT solver | License | solve |

Picat System Call or Interface | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cvc4 | open source | solve([cvc4],Vars) |

cvc4 TempFile > SolFile

|

link |

| z3 | open source | solve([z3],Vars) |

Picat calls z3. This is the default. | link |

| other | n/a |

solve([dump],Vars) solve([dump],Vars)

|

Dump the constraints in SMT-LIB2 format to stdout or to |

n/a |

Two other options are:

-

logic$(Logic)$ : Instruct the SMT solver to use$Logic$ in the solving, where$Logic$ must be an atom or a string, and the specified logic must be available in the SMT solver. The default logic for Z3 is “LIA”, and another suggestion is "QF_FD". The default logic for CVC4 is “NIA”. -

tmp$(File)$ : Dump the SMT-LIB2 format to$File$ rather than the default file “__tmp.smt2”, before calling the SMT solver. The name File must be a string or an atom that has the extension name “.smt2”. When this file name is specified, the SMT solver will save the solution into a file name that has the same main name as$File$ but the extension name “.sol”.

Rabbit hole (the biggest): The world of theorem provers associated research into the boundaries of NP and decidability is about as big a rabbit hole as possible and sweeps in all the big names of Turing, Curry, Howard, Gödel, Russell, Frege, and many more.

Here's a sample program in Lean, a theorem proving programming language, for solving some linear inequality constraints. Gotta love the keyword grind for searching the solution space:

example (x y : Int) :

27 ≤ 11*x + 13*y → 11*x + 13*y ≤ 45

→ -10 ≤ 7*x - 9*y → 7*x - 9*y > 4 := by

grind

Should you wish to see into the current state of the related P vs. NP problem, may I recommend this book by Avi Wigderson that I made it halfway through: https://www.math.ias.edu/avi/book.

MIP solves problems with real (continuous), integer, or binary decision variables or any mixture of these. This is as opposed to LP, linear programming, which only allows for continuous solutions. Both, however, are based on numerical linear algebra techniques. MIP algorithms for finding solutions in the search space include branch-and-bound, branch-and-cut, cutting plans, interior-point methods, Lagrangian relaxation, and Simplex.

To use the mip module in Picat, you need to install an external MIP solver and invoke solve with the name of the solver. Picat will export a file with the appropriate format and then call the external solver. Options are:

| MIP solver | License | solve |

Picat System Call or Interface | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cbc | open source | solve([cbc],Vars) |

cbc TempFile solve -solu SolFile

|

link |

| glpk | open source | solve([glpk],Vars) |

glpsol -lp -o SolFile TempFile

|

link |

| scip | open source | solve([scip],Vars) |

Internal C interface that requires you to build Picat from source with SCIP enabled | |

| gurobi | paid | solve([gurobi],Vars) |

gurobi_cl ResultFile=SolFile TempFile

|

link |

| CPLEX | paid |

solve([dump],Vars)

|

You have load the File into CPLEX | link |

When using mip, if you want real valued solutions (non-integer), then you need to specify an interval for the domain variable in the form 1.34 or 2.0.

Also, nonlinear constraints are not allowed. For example, you can't do this:

import mip.

main =>

X :: 0.0..100.0,

2**X #= 31,

solve([glpk],X),

println(x=X).

results in

*** error(dvar_expected(_a18),nonlinear_constraint)

Fun fact: Simplex and interior-point were the two algorithms that IBM's OSL software implemented, and I documented in 1989. CPLEX is OSL's "descendant" sort of. OSL is more directly an ancestor of the open source COIN-OR tools and CPLEX was an IBM acquisition in 2009. I fear a rabbit hole coming on....

https://adventofcode.com/2016/day/15

The problem from AOC:

When a button is pressed, a capsule is dropped and tries to fall through slots in a set of rotating discs to finally go through a little hole at the bottom and come out of the sculpture. If any of the slots aren't aligned with the capsule as it passes, the capsule bounces off the disc and soars away. You feel compelled to get one of those capsules.

The discs pause their motion each second and come in different sizes; they seem to each have a fixed number of positions at which they stop. You decide to call the position with the slot 0, and count up for each position it reaches next.

Furthermore, the discs are spaced out so that after you push the button, one second elapses before the first disc is reached, and one second elapses as the capsule passes from one disc to the one below it. So, if you push the button at time=100, then the capsule reaches the top disc at time=101, the second disc at time=102, the third disc at time=103, and so on.

The button will only drop a capsule at an integer time - no fractional seconds allowed.

For example, at time=0, suppose you see the following arrangement:

Disc #1 has 5 positions; at time=0, it is at position 4.

Disc #2 has 2 positions; at time=0, it is at position 1.

If you press the button exactly at time=0, the capsule would start to fall; it would reach the first disc at time=1. Since the first disc was at position 4 at time=0, by time=1 it has ticked one position forward. As a five-position disc, the next position is 0, and the capsule falls through the slot.

Then, at time=2, the capsule reaches the second disc. The second disc has ticked forward two positions at this point: it started at position 1, then continued to position 0, and finally ended up at position 1 again. Because there's only a slot at position 0, the capsule bounces away.

If, however, you wait until time=5 to push the button, then when the capsule reaches each disc, the first disc will have ticked forward 5+1 = 6 times (to position 0), and the second disc will have ticked forward 5+2 = 7 times (also to position 0). In this case, the capsule would fall through the discs and come out of the machine.

However, your situation has more than two discs; you've noted their positions in your puzzle input. What is the first time you can press the button to get a capsule?

--- Part Two ---

After getting the first capsule (it contained a star! what great fortune!), the machine detects your success and begins to rearrange itself.

When it's done, the discs are back in their original configuration as if it were time=0 again, but a new disc with 11 positions and starting at position 0 has appeared exactly one second below the previously-bottom disc.

With this new disc, and counting again starting from time=0 with the configuration in your puzzle input, what is the first time you can press the button to get another capsule?

This puzzle is perfect for Picat. Some things to notice:

-

Look how long the description is versus the code!

-

The use of parallel lists to encode the problem variables. The first list has the number of positions for each disc,

DPos, and the second list has the position of the disk at time zero,DTZ. This is a common approach. -

As the capsule falls, the equation for

$T_{start}$ for a given$Disc$ is:$(T_{start}+ Distance + Disc_{time-zero}) \mod Disc_{num-positions} = 0$ -

We could code this as a

foreachloop:

foreach (D in 1..DPos.len)

0 #= (T+D+DTZ[D]) mod DPos[D]

end,

-

But because each is zero, the sum is zero, and one line of code looks cooler than three. So we used

sum(...) #= 0. -

Because we are looking to know the time to press the button, the variable

Tis set to a range of possible values. -

The notation

::means that the variable is within the set of values of the list on the right side of the expression. -

The notation

1..5means "a list with items 1 to 5 i.e., [1,2,3,4,5]" -

We aren't given a range of times, so the program sets the range of the solution T to between 0 and

maxint_small(), which is not very small: it's 72,057,594,037,927,935, aka$2^{56}-1$ , and it is the largest possible value that's allowed in a decision variable, and the smallest value is$-2^{56}-1$ . -

solveis a predicate and unifiesTwith the solution. -

If you wanted all the solutions,

solve_allis a function and looks likeSols = solve_all(T). -

On this problem the

cpsolver is the fastest, but that's not always the case.Solver Part1 Part2 cp 0.04 0.25 sat* 1.88 7.32 mip 0.40 2.40 -

The reason SAT is so much slower is that the domain of T is so large. To get these results the domain was reduced to 10_000_000 to get it to work.

-

Important: In general usage, CP solver tends to be faster than SAT for easy problems, but for harder problem SAT tends to be faster. But whether a problem is "easy" or "hard" often can only be determined by testing it.

-

In section "2.4 Minesweeper - Using SAT" in the Picat constraint programming book, CP beats SAT for

$N \le 430$ and above that SAT wins.

import cp.

main =>

time(Part1 = go([17,3,19,13,7,5],

[15,2,4,2,2,0])), %0.04 sec

printf("Answer Part 1: %w\n",Part1), % 400_589

time(Part2 = go([17,3,19,13,7,5,11],

[15,2,4,2,2,0,0])), % 0.25 sec

printf("Answer Part 2: %w\n",Part2). % 3_045_959

go(DPos,DTZ) = T =>

%(Time + Dist + Time Zero Position) mod Disc Positions

T :: 0..maxint_small(), % 72_057_594_037_927_935

T :: 0..10_000_000, % for SAT also note use of _ sugar to make large number readable

sum([(T+D+DTZ[D]) mod DPos[D] : D in 1..DPos.len]) #=0,

solve([$min(T)],T).

https://www.janestreet.com/bug-byte/

Bug Byte

Fill in the edge weights in the graph below with the numbers 1 through 24, using each number exactly once. Labeled nodes provide some additional constraints:

The sum of all edges directly connected to this node is M.

There exists a non-self-intersecting path starting from this node where N is the sum of the weights of the edges on that path. Multiple numbers indicate multiple paths that may overlap.

Once the graph is filled, find the shortest (weighted) path from to and convert it to letters (1=A, 2=B, etc.) to find a secret message.

In Picat, here's a solution. The nodes and edges are defined and then the constraints about the known values of nodes and possibly values for the edge weights. Each constraint reduces the search space.

The constraint in this program are all_distinct, #=, #^ and #<=.

all_distinct means that the values of the list of edges are all different from each other. When combined with the previous line that puts them in the range of 1 to 24, that means the edges will contain every possible value between 1 and 24.

The #= constraint syntax ensures that the left and right side are equal. Another way to look at this is that the constraint tells the solver module (in this case cp) to try to find a set of values of left and right that are equal.

#<= is less than or equal and #^ is the logical XOR.

Some more notes:

V :: 1..24 means that V is a variable that could be set to any number between 1 and 24, inclusive. Further constraints will limit this, but initially each V is open to all possible values in this range.

The line EdgeVars = [(Edge, V) : Edge in Edges, V :: 1..24] results initially in this:

[((A,B),_09b8::[1 ..24]),((A,D),_0a80::[1 ..24]),((B,S),_0b48::[1 ..24]),((C,H),_0c10::[1 ..24]),((D,S),_0cd8::[1 ..24]),((D,H),_0da0::[1 ..24]),((S,I),_0e68::[1 ..24]),((F,I),_0f30::[1 ..24]),((G,J),_0ff8::[1 ..24]),((H,J),_010c0::[1 ..24]),((H,K),_01188::[1 ..24]),((I,J),_01250::[1 ..24]),((I,L),_01318::[1 ..24]),((J,K),_013e0::[1 ..24]),((J,L),_014a8::[1 ..24]),((K,M),_01570::[1 ..24]),((K,P),_01638::[1 ..24]),((K,N),_01700::[1 ..24]),((L,O),_017c8::[1 ..24]),((M,N),_01890::[1 ..24]),((M,O),_01958::[1 ..24]),((N,E),_01a20::[1 ..24]),((O,E),_01ae8::[1 ..24]),((Q,L),_01bb0::[1 ..24])]

The _xxxx is a unique identifier for the individual decision variable V and the ::[1..24] shows that it has a range of possible values that will have to be constrained.

If we added a sum constraint:

EdgeVars = [(Edge, V) : Edge in Edges, V :: 1..24],

sum([V : (_, V) in EdgeVars]) #= 30

The result would be:

[((A,B),_09b8::[1 ..7]),((A,D),_0a80::[1 ..7]),((B,S),_0b48::[1 ..7]),((C,H),_0c10::[1 ..7]),((D,S),_0cd8::[1 ..7]),((D,H),_0da0::[1 ..7]),((S,I),_0e68::[1 ..7]),((F,I),_0f30::[1 ..7]),((G,J),_0ff8::[1 ..7]),((H,J),_010c0::[1 ..7]),((H,K),_01188::[1 ..7]),((I,J),_01250::[1 ..7]),((I,L),_01318::[1 ..7]),((J,K),_013e0::[1 ..7]),((J,L),_014a8::[1 ..7]),((K,M),_01570::[1 ..7]),((K,P),_01638::[1 ..7]),((K,N),_01700::[1 ..7]),((L,O),_017c8::[1 ..7]),((M,N),_01890::[1 ..7]),((M,O),_01958::[1 ..7]),((N,E),_01a20::[1 ..7]),((O,E),_01ae8::[1 ..7]),((Q,L),_01bb0::[1 ..7])]

Given the limit of 30 for the sum of all the decision variables, the constraint solver has determined that the maximum value of each variable now is 7. Note: sometimes the solver cannot do this domain reduction before the call to solve.

We will need a different set of constraints to solve the bug byte, and they are in the code below. But before you look at it, some things to note:

- The comments say that we only need

C,F, andGto solve. How was this determined? Through trial and error! Someone smarter than me may have been able to figure it out, but I had to go and manually try and figure out combinations to solve. - This was one of my first Picat programs, and it took me a long time and a lot of confusion to start to understand what exactly I was "solving" and how to represent the problem in code.

- The shortest path code was lifted right out of the Picat book, with a slight modification for this problem.

- The shortest path uses

tableand the(+,+,+,-,min)indicates that the first three arguments,Graph,X,Y, are inputs, the fourth,Path, is an output, and fifth,WL, aka weight, is to be minimized. - This Prolog-style shortest path is a mind bender for me still, and it really shows how odd logic programming can feel. The code says:

- If X and Y have an edge between them, that's the shortest path.

- If not, the

?=>on the first rule, then the shortest path is from X to Z and then Z to Y. - What? Huh? How?

- Yes, that's it. Picat searches over the entire space and returns the one with the minimum W

import cp.

main =>

% Define the graph with nodes and edges

Nodes = ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'I', 'J', 'K', 'L', 'M', 'N', 'O', 'P', 'Q', 'S'],

Edges = [('A', 'B'), ('A', 'D'),

('B', 'S'),

('C', 'H'),

('D', 'S'), ('D', 'H'),

('S', 'I'),

('F', 'I'),

('G', 'J'),

('H', 'J'), ('H', 'K'),

('I', 'J'), ('I', 'L'),

('J', 'K'), ('J', 'L'),

('K', 'M'), ('K', 'P'), ('K', 'N'),

('L', 'O'),

('M', 'N'), ('M', 'O'),

('N', 'E'),

('O', 'E'),

('Q', 'L')],

% Edges are tuples of nodes and weights in range 1..24

EdgeVars = [(Edge, V) : Edge in Edges, V :: 1..24],

% Unique edge weights

% Reduce search space to 24! = 6,204,484,903,168,028,160

all_distinct([V : (_, V) in EdgeVars]),

% Constraint to enforce known edge weights

% Reduce search space to 19! = 121,645,100,408,832,000

KnownWeights = [(('D','S'), 12),

(('J', 'K'), 24),

(('K', 'N'), 7),

(('I', 'L'), 20)],

foreach((Edge, Weight) in KnownWeights),

member((Edge, Weight), EdgeVars)

end,

% Constraint to enforce known sum of weights for nodes

% Reduce search space to 48

KnownSums = [('A', 17),

('B', 3),

('H', 54),

('I', 49),

('J', 60),

('K', 79),

('L', 75),

('M', 29),

('N', 39),

('O', 25)],

foreach((Node, Sum) in KnownSums),

NodeEdges = [(N1, N2) : (N1, N2) in Edges, (N1 = Node ; N2 = Node)],

NodeVars = [V : (Edge, V) in EdgeVars, Edge in NodeEdges],

sum(NodeVars) #= Sum

end,

% Constraint that sum of weight on an edge = KnownPathSum OR

% sum of weight plus min edge on neighbor is <= to KnownPathSums

% only need C, G, and F to reduce search space to 2

KnownPathSums = [

('C', 31),

% ('D', 19),

% ('D', 23),

('G', 6),

% ('G', 9),

% ('G', 16),

('F', 8)],

foreach((Node, Sum) in KnownPathSums),

NodeEdges = [(N1, N2) : (N1, N2) in Edges, N1 = Node],

NodeVars = [V : (Edge, V) in EdgeVars, Edge in NodeEdges],

Neighbors = [N2 : (N1, N2) in Edges, N1 = Node],

NodeOneHopEdges = [(N1, N2) : (N1, N2) in Edges, N1 in Neighbors],

NodeOneHopVars = [V : (Edge, V) in EdgeVars, Edge in NodeOneHopEdges],

(sum(NodeVars) #= Sum) #^ (sum(NodeVars) + min(NodeOneHopVars) #=< Sum)

end,

Solutions = solve_all([ffc], EdgeVars),

printf("Number of solutions: %d\n", length(Solutions)),

foreach(Solution in Solutions)

AllEdges = Solution ++ [((Y,X), Weight) : ((X,Y), Weight) in Solution],

sp(AllEdges, 'S', 'E', Path, _),

Message = [chr(W+64) : ((X,Y), W) in Path],

println('====================='),

println(Path),

println("Message is: "++Message),

end,

save_solution(Solutions),

println("Done!").

% shortest path adapted from Picat Manual

table (+,+,+,-,min)

sp(Graph,X,Y,Path,WL) ?=>

Path = [((X,Y),Wxy)],

WL = Wxy,

member(((X,Y), Wxy), Graph).

sp(Graph,X,Y,Path,WL) =>

Path = [((X,Z), Wxz)|Path1],

member(((X,Z), Wxz), Graph),

sp(Graph,Z,Y,Path1,WL1),

WL1 = Wzy,

WL = Wxz+Wzy.

% Save to file for use with Python to make a graph

save_solution(Solutions) =>

Out = open("solutions.txt", write),

foreach(Solution in Solutions)

println(Out, Solution)

end,

close(Out).

The output is two potential solutions. Which is close enough for a person to figure out which the right one is. (It's the one that's a word.)

Number of solutions: 2

=====================

[((S,I),18),((I,J),3),((J,L),17),((L,O),16),((O,E),4)]

Message is: RCQPD

=====================

[((S,D),12),((D,H),9),((H,K),14),((K,M),11),((M,O),5),((O,E),4)]

Message is: LINKED

Done!

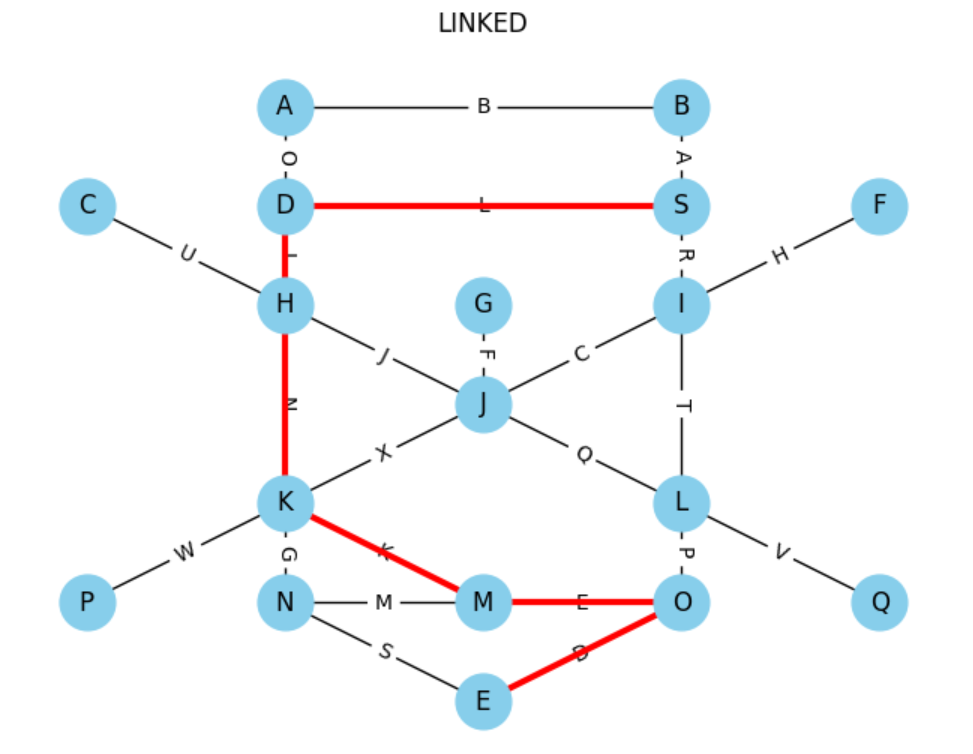

Here's a visual of the shortest path made with Python. The edges are labelled in order from node S to node E: LINKED.

https://adventofcode.com/2015/day/24

Advent of Code 2015 day 24 is a knapsack problem. Typically, AOC problems get harder from day 1 to day 25, but day 24 is a breeze in Picat! Here are the instructions:

Part 1

It's Christmas Eve, and Santa is loading up the sleigh for this year's deliveries. However, there's one small problem: he can't get the sleigh to balance. If it isn't balanced, he can't defy physics, and nobody gets presents this year.

No pressure.

Santa has provided you a list of the weights of every package he needs to fit on the sleigh. The packages need to be split into three groups of exactly the same weight, and every package has to fit. The first group goes in the passenger compartment of the sleigh, and the second and third go in containers on either side. Only when all three groups weigh exactly the same amount will the sleigh be able to fly. Defying physics has rules, you know!

Of course, that's not the only problem. The first group - the one going in the passenger compartment - needs as few packages as possible so that Santa has some legroom left over. It doesn't matter how many packages are in either of the other two groups, so long as all of the groups weigh the same.

Furthermore, Santa tells you, if there are multiple ways to arrange the packages such that the fewest possible are in the first group, you need to choose the way where the first group has the smallest quantum entanglement to reduce the chance of any "complications". The quantum entanglement of a group of packages is the product of their weights, that is, the value you get when you multiply their weights together. Only consider quantum entanglement if the first group has the fewest possible number of packages in it and all groups weigh the same amount.

For example, suppose you have ten packages with weights 1 through 5 and 7 through 11. For this situation, some of the unique first groups, their quantum entanglements, and a way to divide the remaining packages are as follows:

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 11 9 (QE=99) | 10 8 2 | 7 5 4 3 1 |

| 10 9 1 (QE=90) | 11 7 2 | 8 5 4 3 |

| 10 8 2 (QE=160) | 11 9 | 7 5 4 3 1 |

| 10 7 3 (QE=210) | 11 9 | 8 5 4 2 1 |

| 10 5 4 1 (QE=200) | 11 9 | 8 7 3 2 |

| 10 5 3 2 (QE=300) | 11 9 | 8 7 4 1 |

| 10 4 3 2 1 (QE=240) | 11 9 | 8 7 5 |

| 9 8 3 (QE=216) | 11 7 2 | 10 5 4 1 |

| 9 7 4 (QE=252) | 11 8 1 | 10 5 3 2 |

| 9 5 4 2 (QE=360) | 11 8 1 | 10 7 3 |

| 8 7 5 (QE=280) | 11 9 | 10 4 3 2 1 |

| 8 5 4 3 (QE=480) | 11 9 | 10 7 2 1 |

| 7 5 4 3 1 (QE=420) | 11 9 | 10 8 2 |

Of these, although 10 9 1 has the smallest quantum entanglement (90), the configuration with only two packages, 11 9, in the passenger compartment gives Santa the most legroom and wins. In this situation, the quantum entanglement for the ideal configuration is therefore 99. Had there been two configurations with only two packages in the first group, the one with the smaller quantum entanglement would be chosen.

What is the quantum entanglement of the first group of packages in the ideal configuration?

Part 2

That's weird... the sleigh still isn't balancing.

"Ho ho ho", Santa muses to himself. "I forgot the trunk".

Balance the sleigh again, but this time, separate the packages into four groups instead of three. The other constraints still apply.

Given the example packages above, this would be some of the new unique first groups, their quantum entanglements, and one way to divide the remaining packages:

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 4 (QE=44) | 10 5 | 9 3 2 1 | 8 7 |

| 10 5 (QE=50) | 11 4 | 9 3 2 1 | 8 7 |

| 9 5 1 (QE=45) | 11 4 | 10 3 2 | 8 7 |

| 9 4 2 (QE=72) | 11 3 1 | 10 5 | 8 7 |

| 9 3 2 1 (QE=54) | 11 4 | 10 5 | 8 7 |

| 8 7 (QE=56) | 11 4 | 10 5 | 9 3 2 1 |

Of these, there are three arrangements that put the minimum (two) number of packages in the first group: 11 4, 10 5, and 8 7. Of these, 11 4 has the lowest quantum entanglement, and so it is selected.

Now, what is the quantum entanglement of the first group of packages in the ideal configuration?

And here's the code. Some things to note:

-

There are two parts and two solution algorithms per part.

-

Bins are represented by a list of 1s and 0s to indicate if a particular weight is in bin 1 or either of bin 2 or bin 3.

-

It doesn't matter which items are in bin 2 vs. bin 3, only that bin 1 represents

$\frac{1}{3}$ of the total. -

In my initial attempts on the problem I solved for bin 2 and bin3 and it took an order of magnitude longer to solve.

-

Faster solving depends very much on selecting the right problem to solve!

-

The first algorithm

go_knuses a modified version of the knapsack algorithm from the Picat book about constraint solving. It does not use thecpsolver module. It a standard BFS with the amazingtableto memoize and speed up. -

The second algorithm uses

cpscalar_productand#=to constrain the solution to the problem statement. -

Algorithm 1 (tabling) is much faster than algorithm 2 (CP), but both are pretty fast. Interestingly part 1 is slower than part 2, which is not usually the case for Advent of Code.

Knapsack CP default CP ffd Part 1 0.010s 53.7s 0.43s Part 2 0.001s 5.4s 0.32s -

The selection solve strategy can drastically affect solve times.The table has two columns for CP. One is the default search strategy

solve(), the second specifiesffd, which mean, according to the Manual.-

degree: Variables are first ordered by degree, i.e., the number of connected variables. -

down: Values are assigned to variables from the largest to the smallest. -

ff: The first-fail principle is used: the leftmost variable with the smallest domain is selected. -

ffd: The same as with the two options: ff and degree.

-

-

A full list of the possible search strategies is on page 100 of the Manual.

-

This is where a little bit of the magic wears off. Having some sense of your problem and how to search it best does help. On the other hand, you can just try all the methods and see which works best.

-

It is not usually clear at the outset which will be the fastest method. See pgs 59-61 in the Picat constraint book for an example of trying all the combinations of solve options on a Magic Squares problem.

-

Regardless, I found the CP version of the problem easier to grok and less CS major than the recursive graph search of the standard knapsack. And that's why we're using Picat, right? For the magic of letting the computer search.

-

I used

printlnviareportinside ofsolveto track what's going on because I was having a hard time to get this code to work. -

Picat doesn't support multiple constraints for CP, so we can either solve for

L1orQE. Solving forL1works for part 1, but gives the wrong answer for part 2. And solving forQEhangs. -

The knapsack version works regardless.

import cp.

main =>

% Weights = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11},

Weights = {1,2,3,7,11,13,17,19,23,31,37,41,43,47,53,59,61,67,71,73,79,83,89,97,101,103,107,109,113},

print("===========\n"),

time(go_kn(Weights,sum(Weights)//3, 1)),

printf("===========\n"),

time(go(Weights, sum(Weights)//3, 1)),

printf("===========\n"),

time(go_kn(Weights, sum(Weights)//4, 2)),

printf("===========\n"),

time(go(Weights, sum(Weights)//4, 2)),

printf("===========\n").

go(Weights,Target,Q) =>

printf("Constraint Solution Part %w\n",Q),

assign_bin1(Weights,Target,Bins,QE,L1),

solve($[degree,updown,min(QE),

report(printf("Found %w, %w %w\n", L1, QE, Bins))],

Bins),

Bin1Weights = [BW: I in 1..Weights.length, BW=Bins[I]*Weights[I],BW>0],

printf("Bin 1: %w ",Bin1Weights),

printf("CP Answer Part %d: %w\n",Q,prod(Bin1Weights)).

assign_bin1(Weights,Target,Bins,QE,L1) =>

N = length(Weights),

Bins = new_array(N),

Bins :: 0..1,

scalar_product(Weights, Bins, Target),

L1 #= sum(Bins), % for reporting bin1 size

QE #= prod([max(1,(Bins[I]*Weights[I])) : I in 1..N]). % Minimize QE = product of weights

go_kn(Weights,Target,Q) =>

printf("Knapsack Solution Part %w\n",Q),

knapsack(to_list(Weights),Target,Sack,Val),

printf("Bin 1: %w\n",Sack),

printf("Table Answer Part %d: %w\n",Q,second(Val)).

% knapsack modified from https://picat-lang.org/picatbook2015/constraint_solving_and_planning_with_picat.pdf

% Val = (Length of Sack, QE)

% Item is a list of weights

table(+,+,-,min)

knapsack(_,C,Sack,Val), C<=0 =>

Sack = [], Val = (1,1).

knapsack([_|L],C,Sack,Val), C > 0 ?=>

knapsack(L,C,Sack,Val).

knapsack([IWeight|L],C,Sack,Val), C >= IWeight =>

Sack = [IWeight|Sack1],

knapsack(L,C-IWeight,Sack1,Val1),

Val = (first(Val1)+1,second(Val1)*IWeight).

Here's some of the output:

===========

Knapsack Solution Part 1

Bin 1: [1,89,101,107,109,113]

Table Answer Part 1: 11846773891

CPU time 0.007 seconds.

===========

Constraint Solution Part 1

Found 9, 47812606799854 {0,1,0,0,0,1,0,1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,1,1}

Found 8, 30655058205881 {0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1,1,1}

Found 7, 23538056666 {1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,1,1,1,0}

Found 6, 11846773891 {1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1,0,1,1,1}

Bin 1: [1,89,101,107,109,113] CP Answer Part 1: 11846773891

CPU time 0.432 seconds.

The planner module is, as far as I know, unique to Picat. It lets you define a starting state, action to create the next state, the final/goal state, and then just solve it. It's quite amazing!

Planner acts as high-level interface to the underlying solver and mechanics of tabling and goal state checking.

Here's an example from the documentation for the programming language Curry, which combines functional and logic paradigms. https://curry-lang.org/docs/tutorial/html/curry-tutorial.Ch6.S1.html#SS3

The “blocks world” consists of 3 possibly empty piles, labeled p, q and r, of unique blocks labeled A, B, C, etc. “Start” and “Final” below are two examples from blocks world.

A blocks world “problem” consists of two worlds, like Start and Final above. Its solution consists in the moves that produce the second world from the first one. A “move” transfers the block on top of a pile to the top of another pile. No other blocks are affected by the move.

Here's a solution with the Picat planner.

Note: A neat trick here is the use of () and ; (meaning "or") to create the equivalent of a case statement in another language. Although it's not really a case statement. More detail on this here.

import planner.

main =>

problem(S),

best_plan(S,Plan), % solves the problem S

println(S[1]), % prints the first state

foreach (Step in Plan)

println(Step) % prints each state

end,

printf("Solution cost: %w\n", length(Plan)).

% uncomment an S to run it

problem(S) =>

% S = [[[a,b],[],[]], [[],[a,b],[]]]. % simple

% S = [[[a,b],[],[]], [[],[b,a],[]]]. % simple

S = [[[a,b,c,d,e],[],[]], [[],[c,b,a,d,e],[]]]. % difficult

% the goal state

final(State), State[1] == State[2] => true.

% action predicate defines how to go to the next state: NextS

% Action variable is used to write the chosen step to the log

action([[S1,S2,S3],G],NextS,Action,Cost) =>

% pattern match on all the possible moves

% this works like a case statement although all options are evaluated

% Goal is G and is passed through as part of the state

(

S1 = [H1|T1],

NewS1 = T1,

NewS2 = [H1|S2],

NewS3 = S3,

Action = $("1->2",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

;

S1 = [H1|T1],

NewS1 = T1,

NewS2 = S2,

NewS3 = [H1|S3],

Action = $("1->3",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

;

S2 = [H2|T2],

NewS1 = S1,

NewS2 = T2,

NewS3 = [H2|S3],

Action = $("2->3",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

;

S2 = [H2|T2],

NewS1 = [H2|S1],

NewS2 = T2,

NewS3 = S3,

Action = $("2->1",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

;

S3 = [H3|T3],

NewS1 = [H3|S1],

NewS2 = S2,

NewS3 = T3,

Action = $("3->1",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

;

S3 = [H3|T3],

NewS1 = S1,

NewS2 = [H3|S2],

NewS3 = T3,

Action = $("3->2",NewS1,NewS2,NewS3)

),

Cost = 1, % the cost for a given step

NextS = [[NewS1,NewS2,NewS3],G]. % the next state.

This outputs:

[abcde,[],[]]

(1->2,bcde,a,[])

(1->2,cde,ba,[])

(1->3,de,ba,c)

(2->3,de,a,bc)

(2->3,de,[],abc)

(1->3,e,[],dabc)

(1->2,[],e,dabc)

(3->2,[],de,abc)

(3->2,[],ade,bc)

(3->2,[],bade,c)

(3->2,[],cbade,[])

Solution cost: 11

https://adventofcode.com/2015/day/22

Advent of Code 2015 day 22. This has a long description, sorry! But hopefully helpful in understanding what's needed.

--- Day 22: Wizard Simulator 20XX ---

Little Henry Case decides that defeating bosses with swords and stuff is boring. Now he's playing the game with a wizard. Of course, he gets stuck on another boss and needs your help again.

In this version, combat still proceeds with the player and the boss taking alternating turns. The player still goes first. Now, however, you don't get any equipment; instead, you must choose one of your spells to cast. The first character at or below 0 hit points loses.

Since you're a wizard, you don't get to wear armor, and you can't attack normally. However, since you do magic damage, your opponent's armor is ignored, and so the boss effectively has zero armor as well. As before, if armor (from a spell, in this case) would reduce damage below 1, it becomes 1 instead - that is, the boss' attacks always deal at least 1 damage.