| description |

|---|

This is a work-in-progress textbook based on teaching materials used in a course delivered at Columbia University in Fall 2018 by Eamonn Bell |

Please download and install the following software in advance of the first class meeting:

- Sonic Visualiser download

- MATCH Plugin for Sonic Visualiser download installation instructions

- Gephi download

- AntConc download

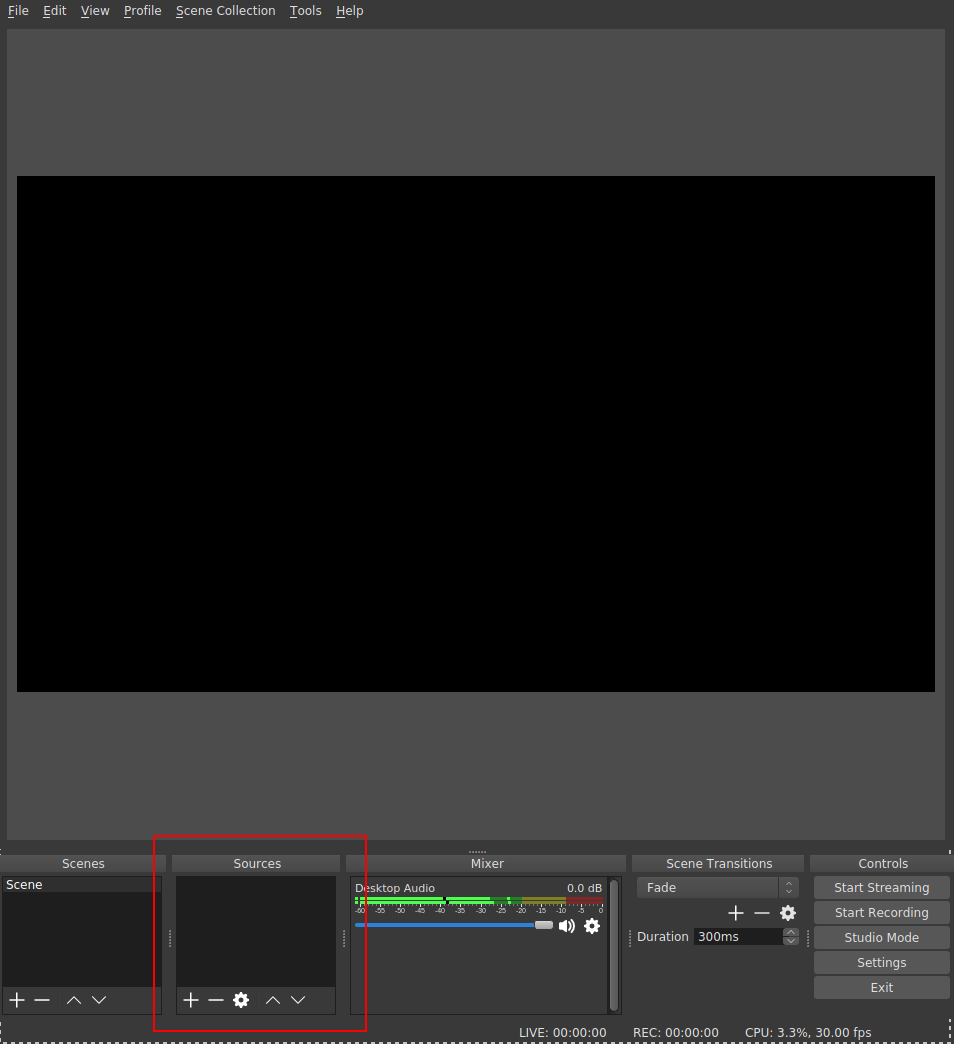

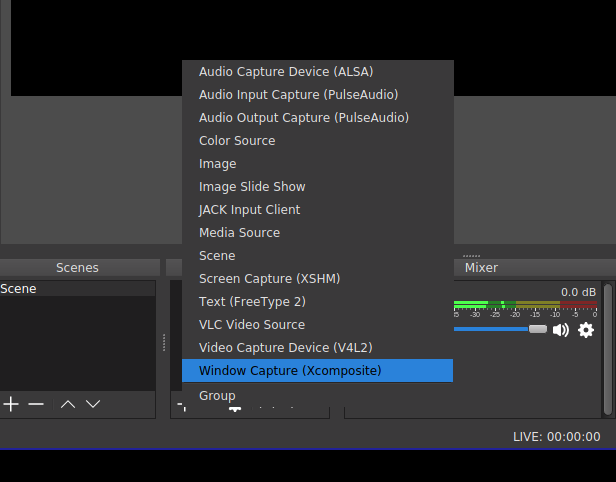

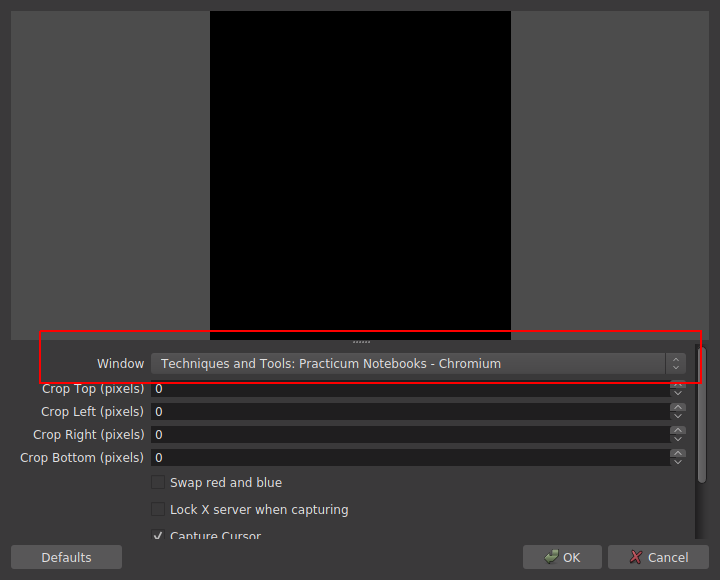

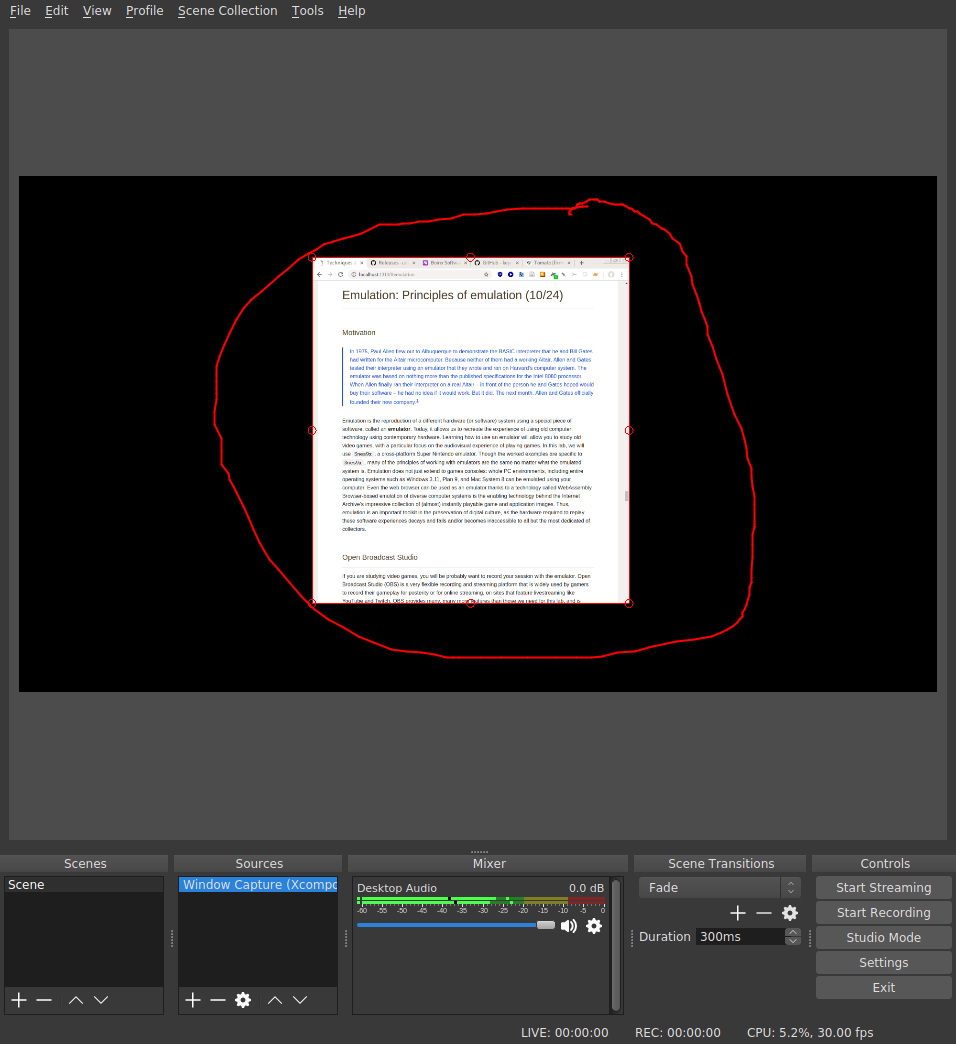

- OBS download

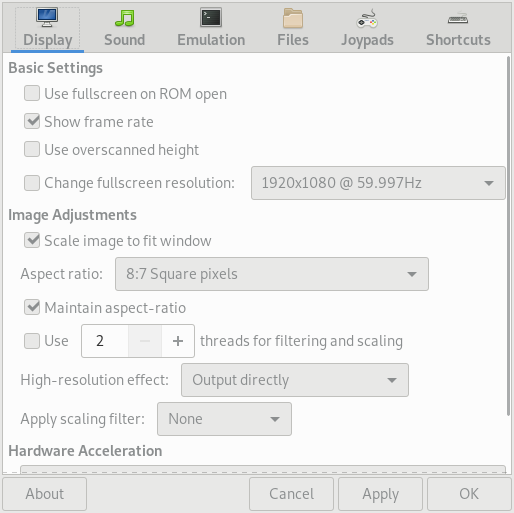

- Snes9x download for Mac download for Windows

- Google Chrome

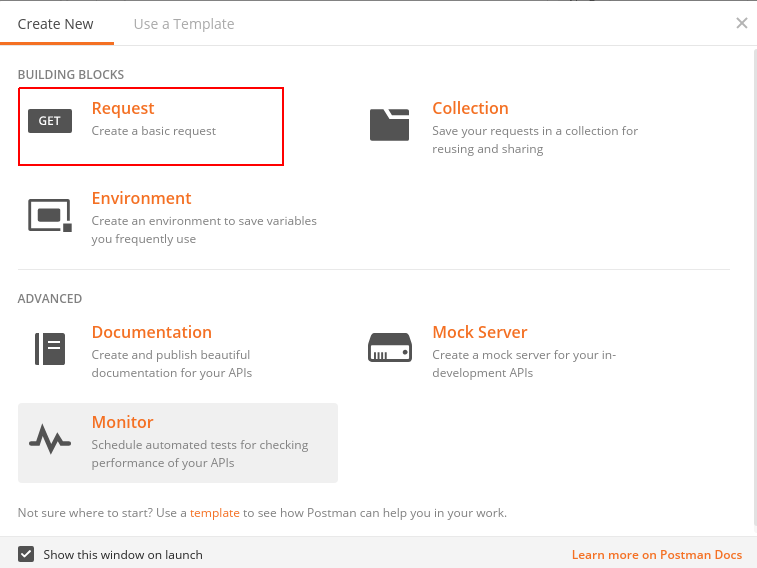

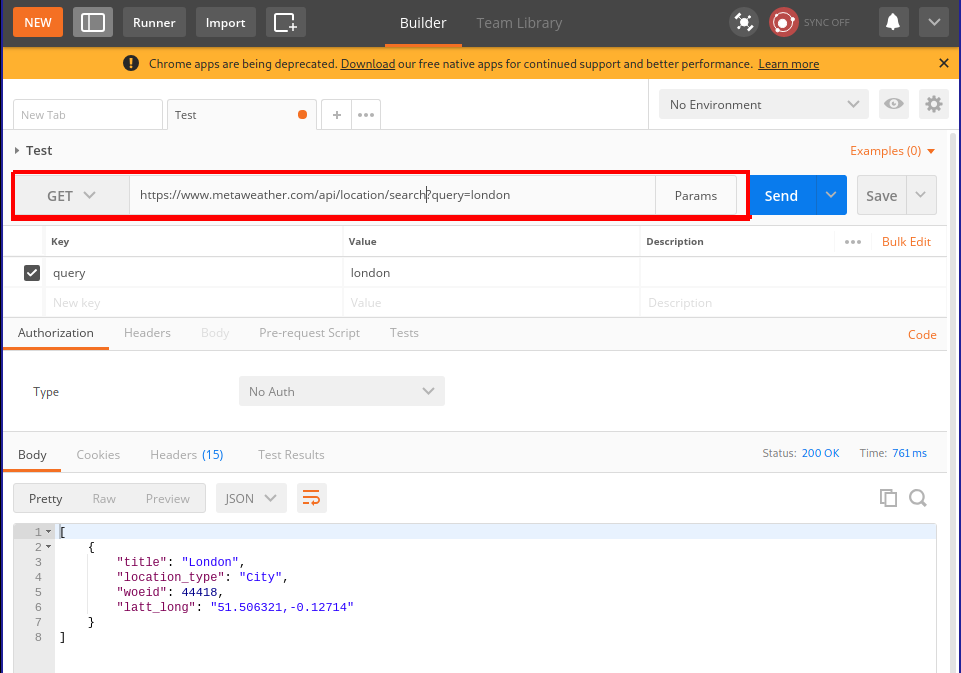

- Postman for Google Chrome download

Please also make sure that you know how to:

For each practicum session, you will be expected to submit a single .zip file containing all your work. Please create a folder for each session, and a folder for each exercise within that folder. Each exercise will specify precisely which files you will have to submit to be considered for full credit for that practicum. These files will be submitted via Courseworks, under the Assignments page.

You should be able to finish the assigned tasks during the scheduled practicum time. If you are finished early, feel free to leave the lab—or stick around and help your peers, if you are interested in learning how to be an effective peer leader. If you do not finish in time, you have until 11:59 p.m. on the day of the practicum session to submit the completed work. You may not take advantage of this extension if you do not attend the entire lab: i.e. attendance at the lab session is compulsory.

Read the notebook in advance of the practicum session

In general, I assume no prior expertise with any of these tools, though I expect you to have basic computational literacy as an end user (know how to install and run new programs, organize files on disk, use the Web, etc.). If you are having trouble keeping up, please don’t hesistate to work through your questions at office hours. Some weeks may be more straightforward for you than others: that’s ok. Don’t be afraid to ask for help from me or from your peers during the practicum.

If you find yourself hoping to help your peers or to work through something together, the four social rules described here are worth bearing in mind. They are not binding, but have been shown to be particularly effective in instructional settings, where peer learning is encouraged. In brief:

- no “well, actually”

- try not to act surprised when someone doesn’t know something

- no backseat driving

- no subtle -isms (sexism, racism, etc.)

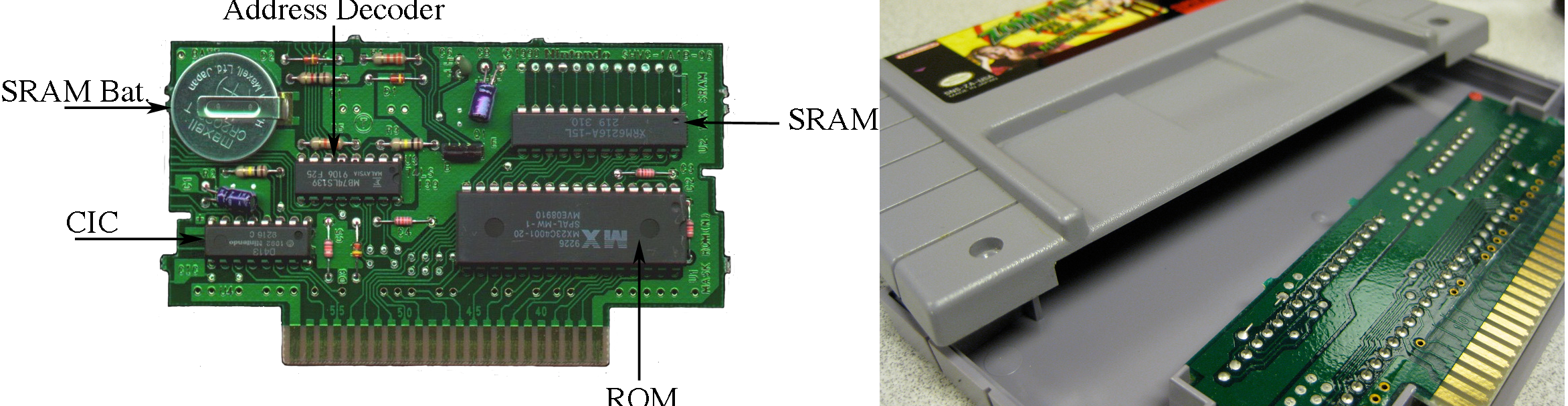

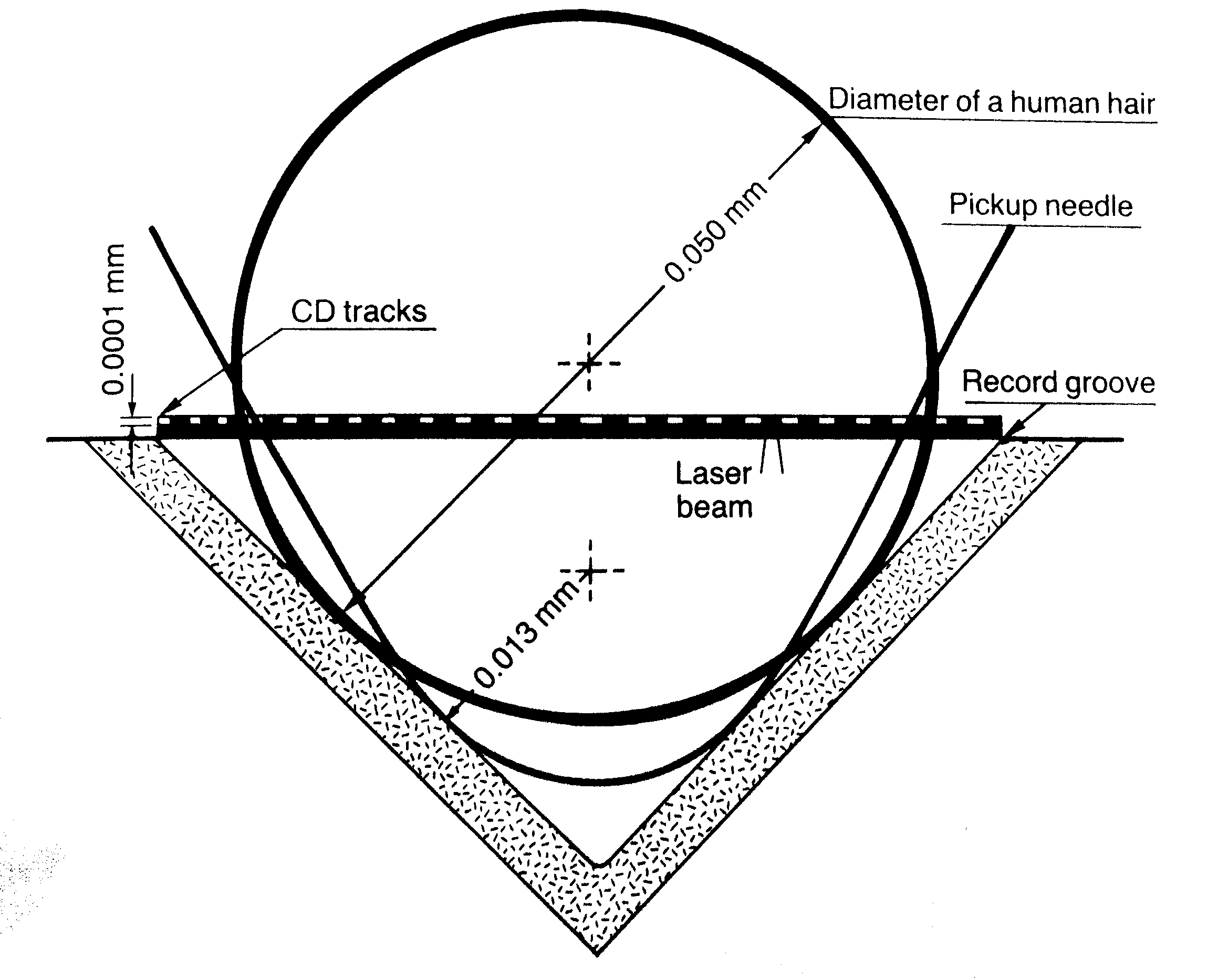

Music is sound and sound is vibrating air. The earliest recording technologies captured the motion of the air and mechanically transfer this motion to a recording surface: first, rotating wax and foil cylinders; eventually, vinyl records. The motion caused by the changing air pressure, traveling through a mechanical linkage, caused a stylus to move creating a groove of varying depth on the recording medium. The contours of this groove are the material trace of the recorded sound. To play back the sound, the flow of motion would essentially be reversed: the rotating disk causes the stylus to move, very slightly, retracing the grooves made during the recording process and causing a loudspeaker cone to vibrate analogously, setting the air in motion more or less as it was recorded, resulting in playback. In the words of Kittler:

The phonograph permitted for the first time the recording of vibrations that human ears could not count, human eyes could not see, and writing hands could not catch up with. Edison’s simple metal needle, however, could keep up—simply because every sound, even the most complex or polyphonous, one played simultaneously by a hundred musicians, formed a single amplitude on the time axis.

Evidently, this is not how recordings are stored in digital media, among them: CD-ROMS, hard-drives, memory sticks, music players, and smartphones. From a digital perspective, the continuous and infinitely divisible motion of air—sound—must be described as a sequence of numbers, by periodically quantifying and recording the intensity of the motion. A digital audio file is essentially a wrapper around a recorded sequence of these observed intensities. The process of taking these observations is called sampling. When an audio signal is detected by a microphone, the motion of the air is first converted into voltage fluctuations, which vary continuously over time: as the air moves, so too does the voltage across the microphone. A piece of hardware called an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) measures these voltage fluctuations over time and converts them into a sequence of numbers, represented digitally (i.e. as a set of discrete observations, almost always stored as a sequence of binary digits, or “bits”).

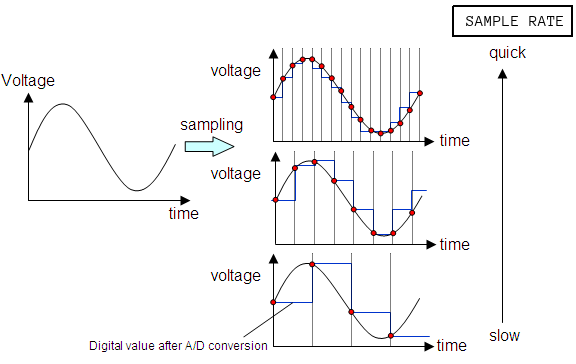

At a fixed number of times per second—typically in the tens of thousands—the ADC takes a measurement of the voltage at that instant, usually relative to some predefined maximum. The sample rate is one parameter of the analog-to-digital conversion process that determines the fidelity of the digitally recorded sound compared to the original source. The diagram shows the effect of changing the sample rate on the “resolution” of the digital audio signal. You can think of this as analogous to resizing a digital image downwards with its concomitant loss of resolution.

A result known as the Nyquist Sampling Theorem shows given the maximum frequency of a periodic component of a complex sound (loosely, the highest “pitch” in a recording), we can always pick a sample rate that is sufficiently high such that the original analog signal can be recovered perfectly from the digitized version, if the analog source was digitized at that sample rate. If these ideas are new to you, you might want to watch this excellent introduction to digital media, though understanding the ins-and-outs of analog-to-digital audio conversion are not critical to completing this practicum session.

Sonic Visualiser (SV) is a toolkit for analyzing digital recordings and is very useful for the study of recorded music. Developed at Queen Mary University of London, it is freely available for a number of operating systems. Tools like this have been used in the study of expressive timing, pitch, dynamics, and vocal timbre (Rings’s contribution), as well as in the forensic study of historical recordings. We will learn how to use SV to examine the content of audio files, annotate the files at the beat level, and compare recordings.

SV is much like any audio editor, but it can load multiple files at once as well as offer a number of different visualizations of the audio data, which can be either overlaid or placed side-by-side. In addition to the relatively straightforward playback features that we would expect from an audio program, SV makes use of the following three key concepts:

- panes: A “slot” corresponding to a single audio file. A given SV session may make use of several panes.

- layers: A visualization that is derived from or tied to a pane. A given pane may have more than one layer. This allows us to superimpose audio visualizations and other data.

- transforms: Algorithmic manipulation of the audio file, including audio effects processing and automatic feature extraction (e.g. beat detection or pitch tracking)

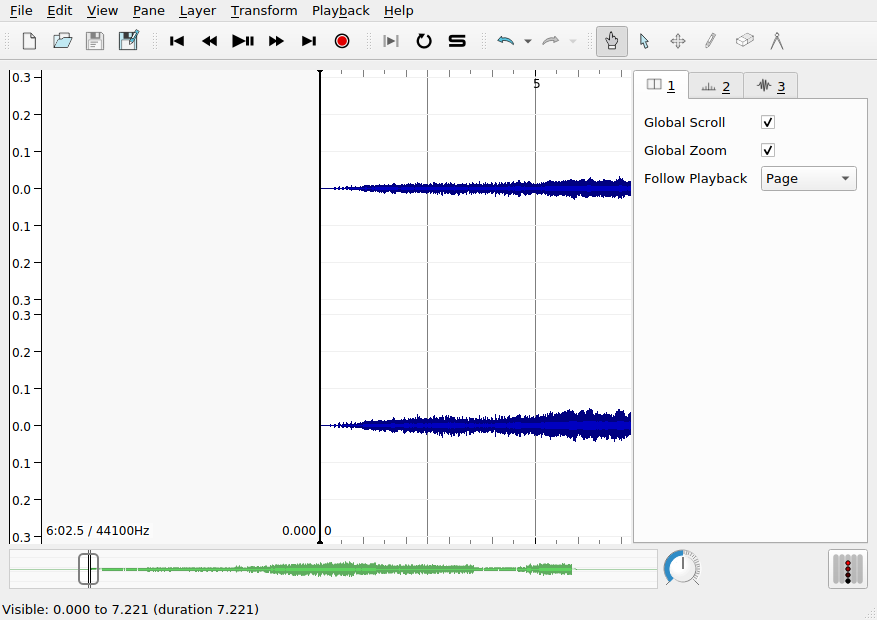

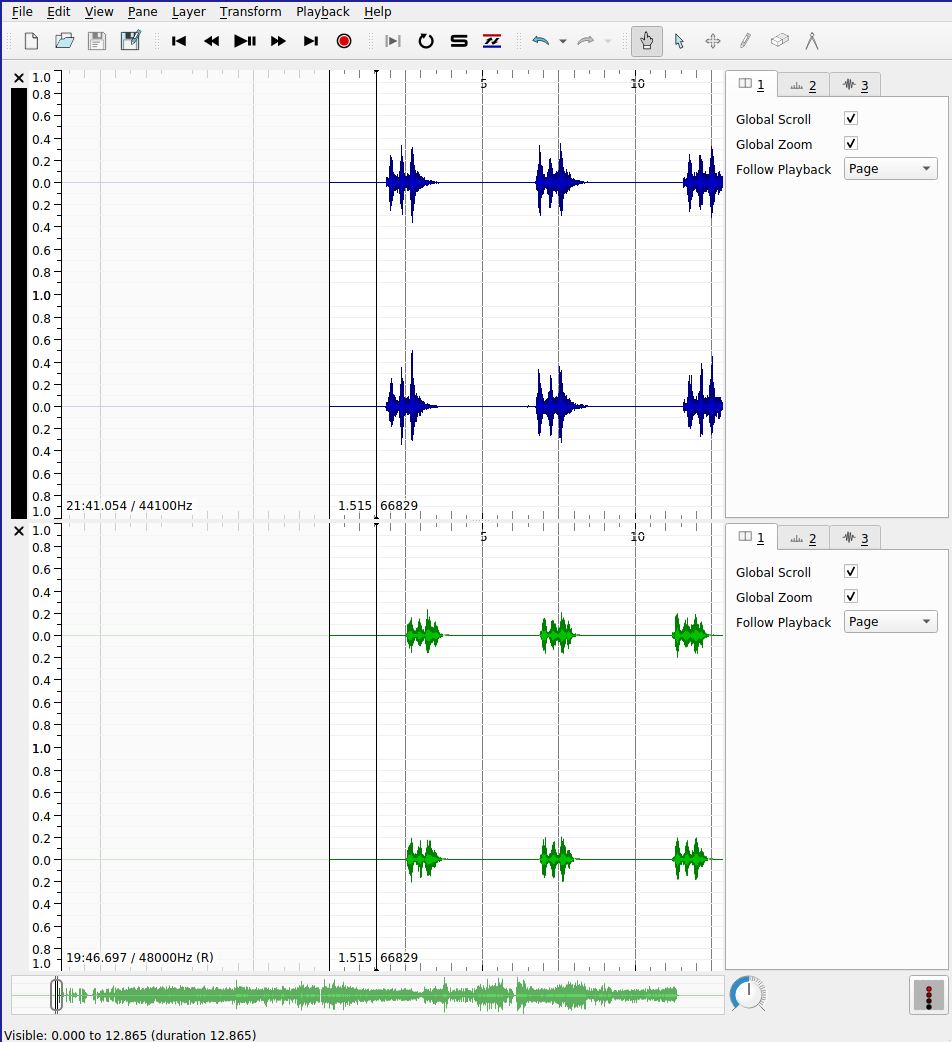

When SV first launches, it will begin with a single pane, with three default layers. However, this pane does not yet contain an audio file. To load a file into the default pane, use File > Open.... Once the file is loaded, it should look something like this:

The three layers in use in this pane are addressable using the settings tabs on the right hand side of the interface, currently shown in the following order:

- The first layer contains global settings for the pane

- The second layer,

Ruler, draws vertical lines at regular intervals to mark the passage of time. Note the range and the units of the x axis. - The third layer,

Waveform, shows the amplitude of the audio signal over time: this is the blue mass visible in the pane. Note the range of the y axis. Is there a unit?

Switching between layers, you can make adjustments to how each layer appears. You can toggle the visibility of a layer using the Show check box on each layer’s settings tab. Unfortunately, reordering layers is not supported.

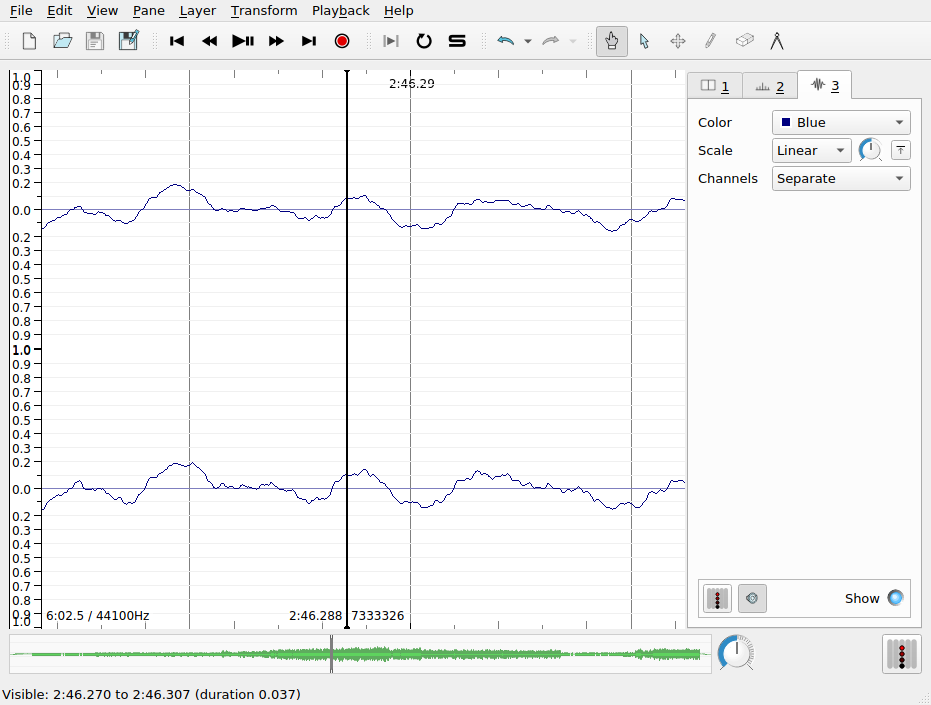

The waveform layer shows the intensity of the sound wave as it evolves over time. Sudden, loud sounds will appear as peaks in the waveform. If you zoom in on the x-axis very close, you can almost see the individual samples. As we zoom out, we get something like the average intensity over time. Intensity is measured here in arbitrary units on a scale from -1 to +1.

Q. There is something slightly misleading about this visualization of the sampled intensity values in SV. Based on your understanding of analog-to-digital conversion, what is it?

There are a couple of important settings to note in the Waveform layer tab:

- scale: Change the scale of the y axis, including a “Normalize to Visible Area” button

- channels: Describe how to treat data from stereo signals

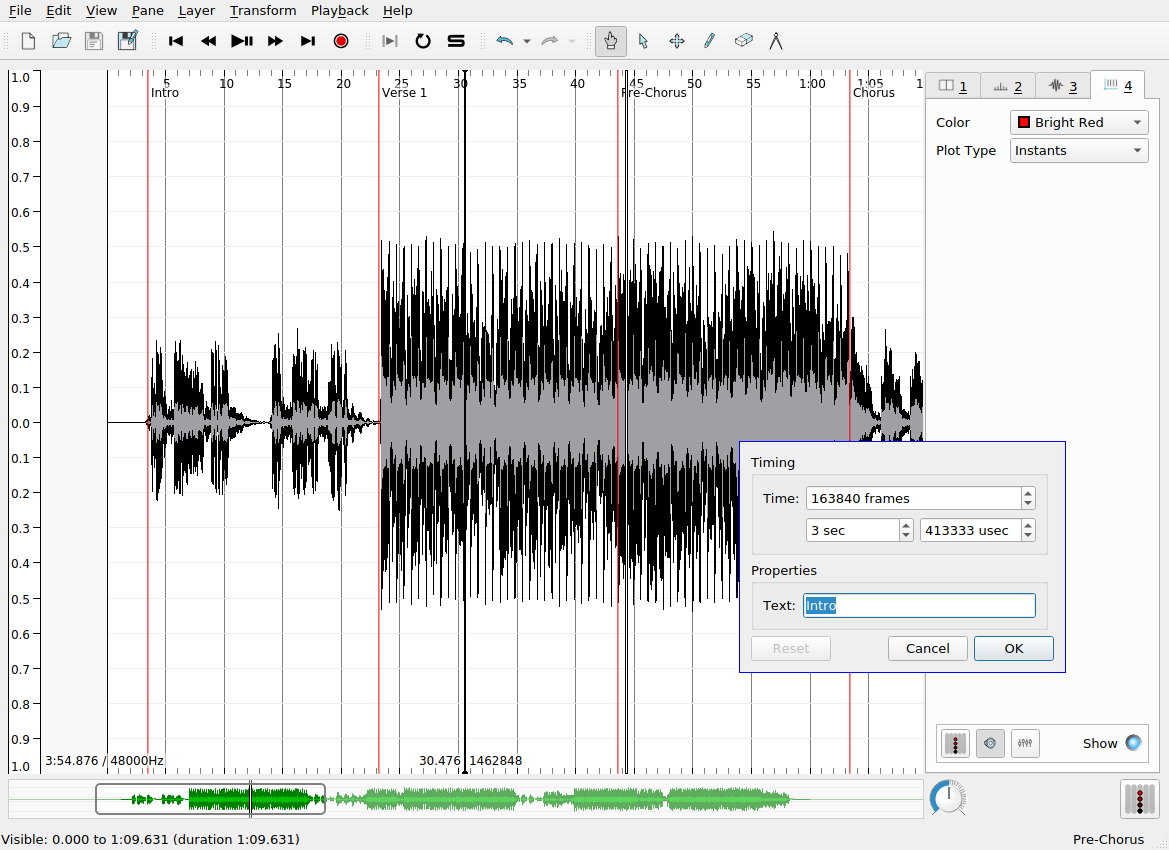

Time instants layers contain instantaneous markers that can be used to “bookmark” certain events in the audio file. For example, time instants can be added to track the pulse of a musical excerpt, to demarcate the major formal sections of a song, or to highlight other interesting moments in an audio recording. Once you have added a time instants layer, and the layer is active in SV (i.e. the corresponding tab is selected), there are two main ways to create an instant:

- During the playback of the audio file, hit the

Returnkey - Alternatively, when the audio is not playing back, use the pen tool (see the main toolbar) to manually add an instant with your mouse

Once an instant has been added, it can be repositioned using the move tool (also in the main toolbar). This is useful, because tapping input will never be perfectly accurate for a number of reasons:

- limitations on human response rates to audio stimuli

- mis-hits or accidental double hits

- generally, operating systems do not provide strong real-time scheduling guarantees for keyboard press events: the latency between keypress and the actual recorded event can be up to 150ms in the worst case, which is inadequate for research purposes

To improve the accuracy of the placement of time instants, you can use the waveform or spectrogram layers as a visual guide to help you locate the onset of the musical event you are interested in tracking. You can use SV’s audio feedback feature, which plays a click or other user-defined sound at the moment of each time instant. To enable this for a time instant layer, make sure the desired layer is select, and click the loudspeaker icon at the bottom of the sidebar. Time instants have labels associated with them, which may be modified by hovering over the instant you wish to label with the navigate (or, alternatively, move) tool. The default label is fairly unhelpfully: “New Point”.

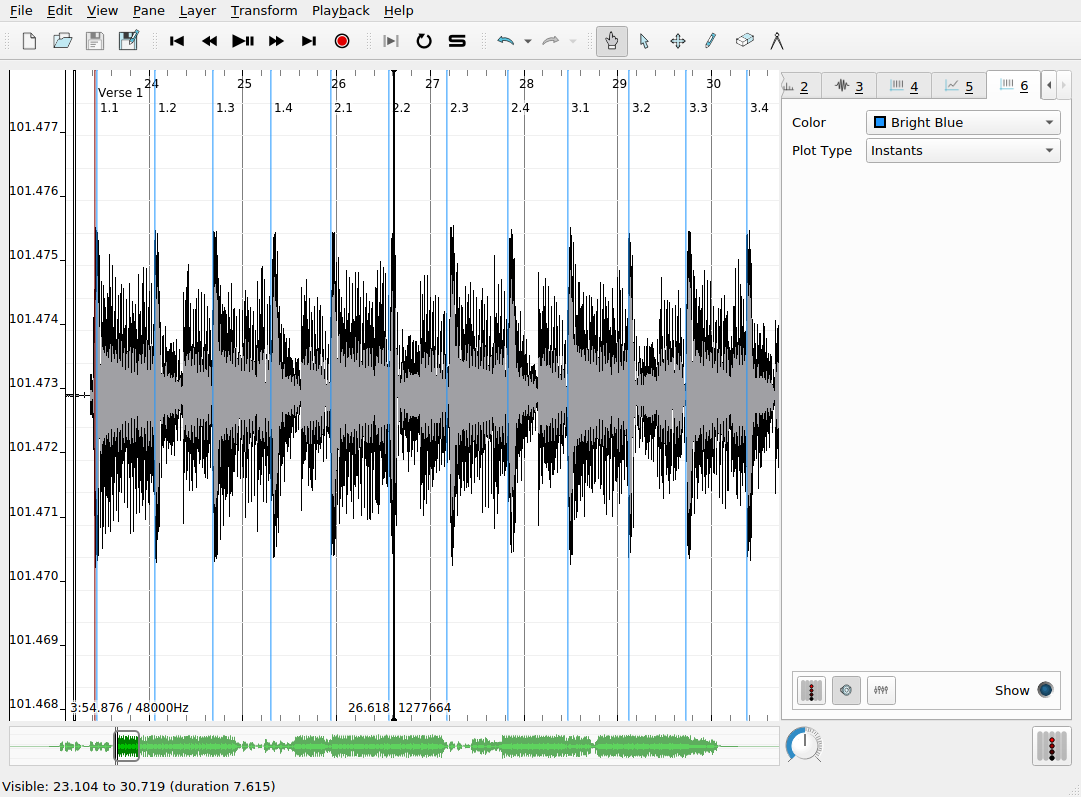

Multiple time instants layers may be overlapped in the same pane to provide annotations at different levels of detail. Here, bright blue time instants show the locations of beats in each measure that I added manually. The labels here indicate the measure number and the beat number (e.g. 3.1 means measure 3, beat 1). SV allows you to automatically label time instants sequentially according to a number of schemes, so that you don’t have to suffer the tedium of inputting the measure and beat numbers manually. This is done as follows:

- Ensure that the desired time instants layer is selected

- Choose from the set of supported ways of generating labels (

Edit > Number New Instants with) Edit > Select AllEdit > Renumber Selected Instants

A common error can reveal itself at this point. If the generated sequential numbering gets “off” in some way, it is usually due to the existence of two instants in the layer at or very near the same time point, effectively creating an undesired duplicate marker for the desired event. You can check for the existence of duplicate instants either by zooming in on the x axis or (more robustly) by revealing a tabular view of the layer data by clicking on Layer > Edit Layer Data. Be aware of this particular kind of dirty data not only in your own data but in also any datasets you might use in your own research that you did not collect yourself—it is more common than might would expect.

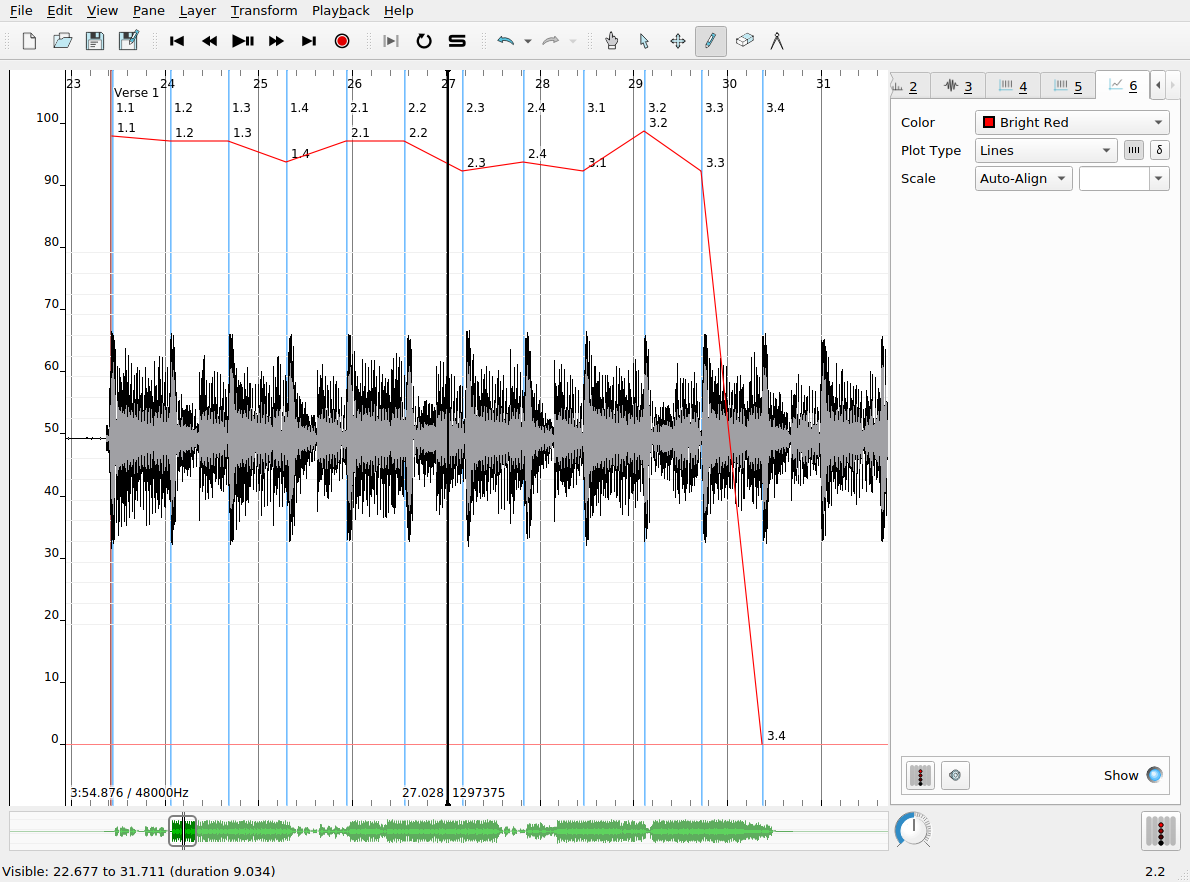

Time values are like time instants, in that they allow us to associate data with a specific timecode in the audio recording. Time values, however, associate real-valued numbers with each instant, which can be used to keep track of the evolution of certain measures made of the audio file over time, charting things like tempo, loudness, etc. Time values can be displayed as a line chart, as shown in the screenshot below. In this example, the time values record the tempo of the music in the recording as computed from the inter-onset interval (i.e. the elapsed time between successive time instants in that layer). To derive the time values from a time instants layer:

- Create a time instants layer and fill it with the instants you are interested in deriving further data from

- Create a new time values layer, which will be, at first, empty

- Navigate to the time instants layer using the tabs in the left-hand sidebar

- Use

Edit > Select All(or a keyboard shortcut) to select all the time instants in the track - Navgiate to the newly created time values layer

- Click

Edit > Paste - A dialog box will pop up with a number of options from which you can choose the rule for assigning values to each instant in the new layer. Each old time instant will have one value associated with in the new layer.

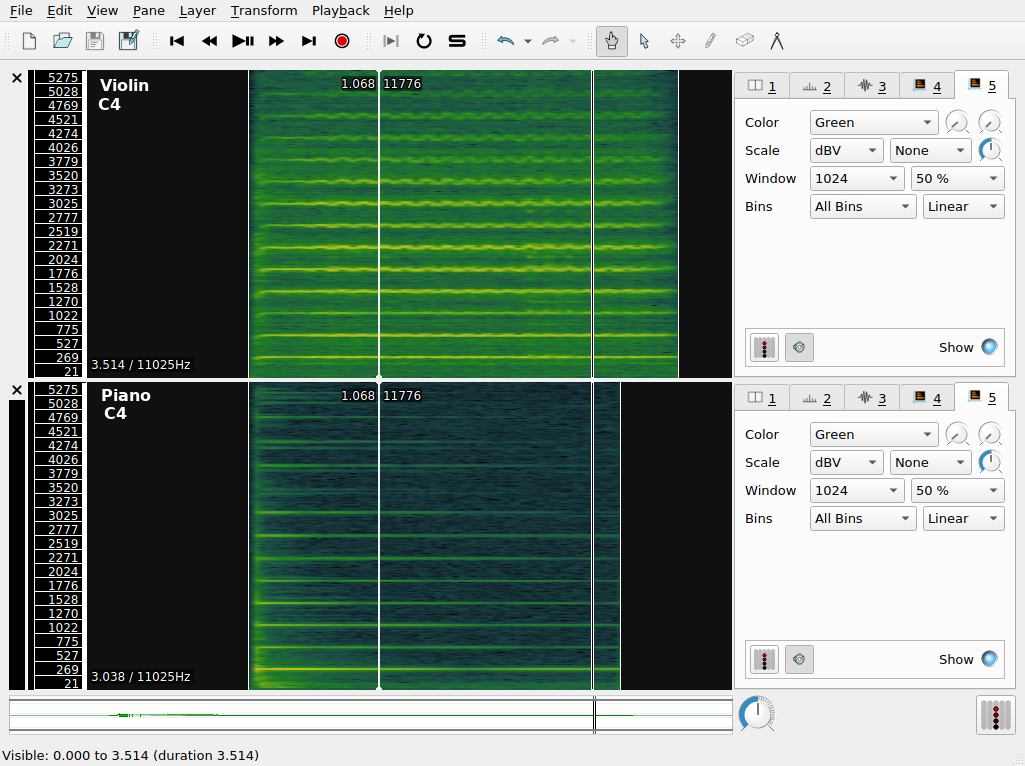

The spectrogram layer shows the results of a spectral analysis of the audio file. All complex sounds can be described as a combination of simpler components of different frequencies (from high to low). Spectral analysis takes an audio signal and splits it up into these components, using an analytic technique whose foundations date back to work done by Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier in 1822. A spectrogram visualizes the results of this analysis in a graphical plot. Time is represented on the x axis, as usual. Unlike the waveform view of the audio signal, the y axis now represents frequency (pitch). Furthermore, the spectrogram has one further visualization dimension: color. The color of the chart at a given x-y coordinate represents the power of that frequency’s contribution to the overall audio signal at that time point. Now, spectrograms are in widespread use and can be used by musicologists to study timbre and other low-level acoustical features of recorded music.

Spectrograms can also be used to examine the acoustic properties of simple sonic events. The figure shows two panes in SV, corresponding to a piano and violin playing the same notated pitch (C4, or “middle C”).

The color scheme in use here ranges from a dark-green (representing the lowest value) through yellow, with the highest values being represented in red. Middle C is approximately 261Hz, so we expect a band around this value to be prominent in the spectrogram. We call this the fundamental frequency. However, it’s apparent that there are other components in the spectrogram. These occur at integer multiples of the middle C frequency; they are called overtones. The overtone structure of a pitched sound is an important determinant of its timbre.

Q. What timbral features that distinguish the violin and the piano to a regular listener can you recognize in the spectrogram?

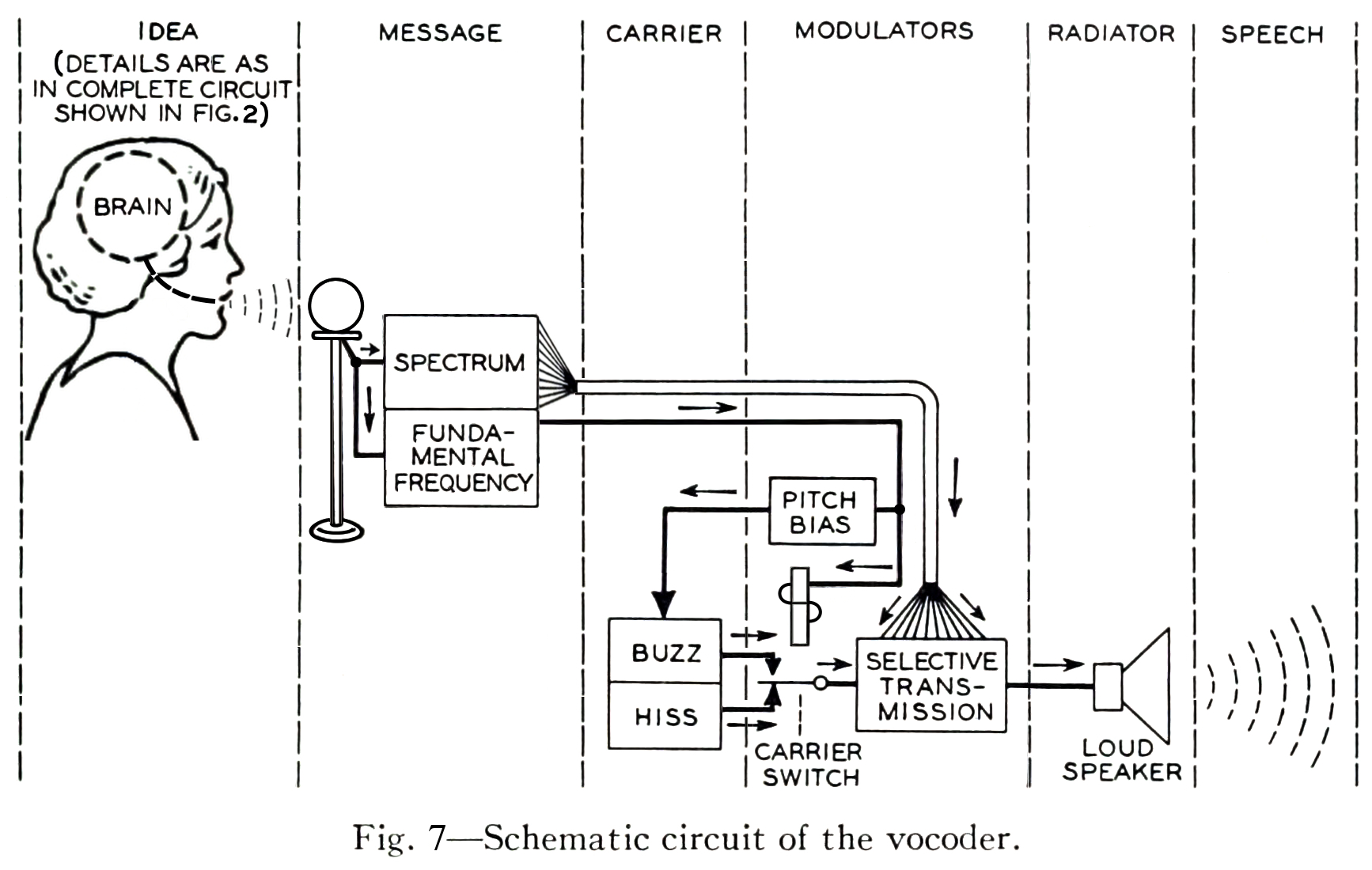

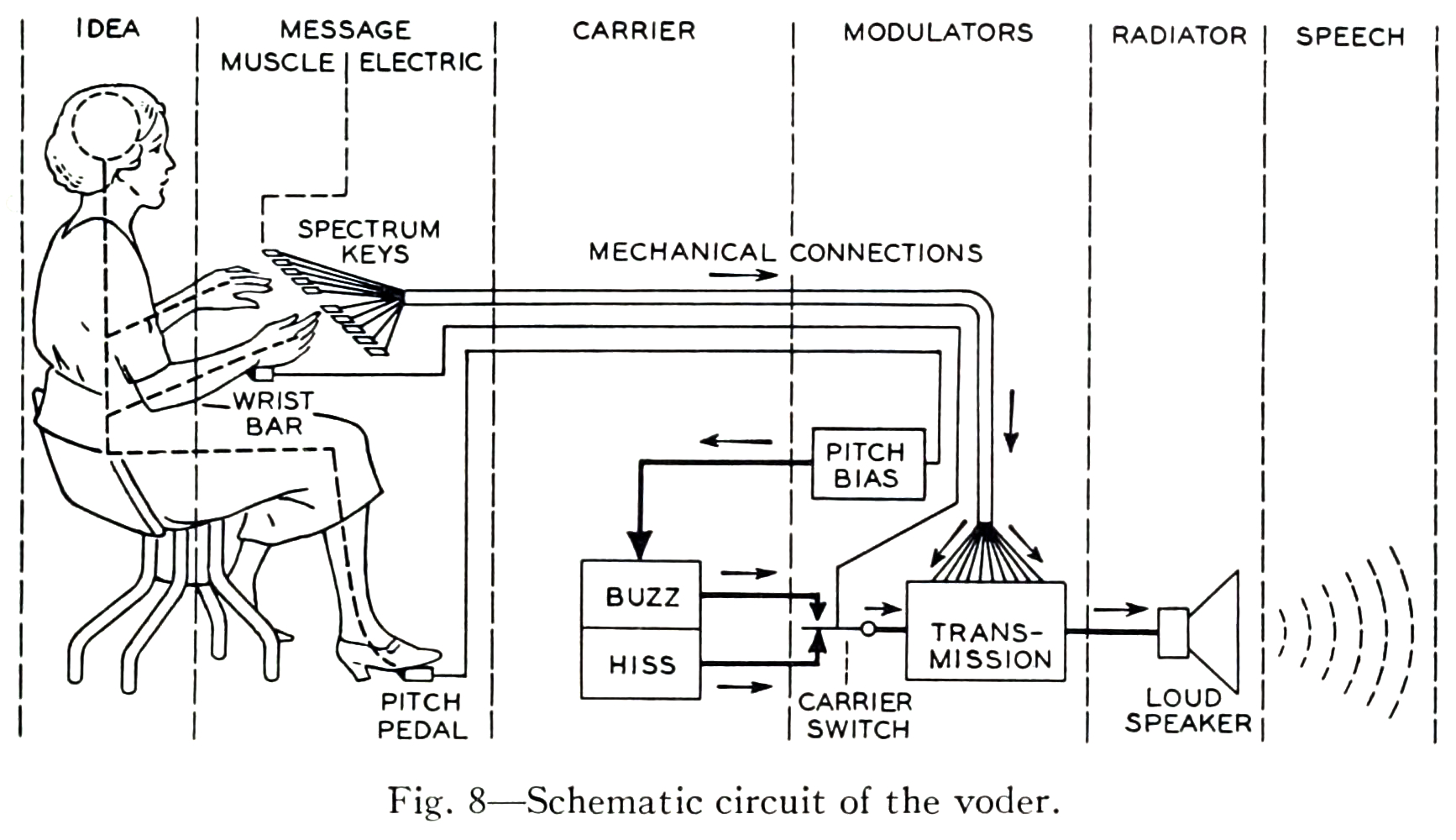

Spectral analysis was also used extensively in the artificial synthesis of speech. The vocoder was developed by Dudley et al. at AT&T Bell Laboratories with the idea of reducing the bandwidth consumed on telephone line based on the principle of analyzing the speaker’s voice before transmission, sending a reduced-size representation of the voice down the wire, and resynthesizing the voice at the other end.

The vocoder team adapted the technologies developed for the vocoder project for use in a public demonstration of artificial speech synthesis in 1939, in a non-commercial tool called the Voder.

The schematic diagrams both emphasize the architectural similarity between the vocoder and the voder, and call attention to their principal difference: the interpolation of a manual human operator of the Voder, who controls the synthesized sound by means of a keyboard. In the vocoder, the human voice enters the system through a microphone and is decomposed into its frequency components by a bank of filters. The results of this decomposition are used in the “modulators” step, to selectively control the mixture resulting frequency components of the synthesized voice appropriate to the input sound. In the Voder, the operator silently uses a keyboard interface to control the mixture, according to their training in the spectral structure of speech phonemes.

This is similar to the spectrogram, except that the range of the y axis is limited to correspond to the range of fundamentals that can be produced with the most common musical instruments (and the human voice). It is useful for musical transcription tasks in combination with the measurement tool.

- Save your work regularly! SV is fairly stable, but it can still crash unexpectedly and sessions are not automatically saved (as far as I know)

- If you are preparing a spectrogram for publication, consider changing the color scheme—especially if your publication or submission requires greyscale images.

First, refer to the instructions of general applicability above.

Extra instructions: Save your SV session file in the same directory as the original wave file for each exercise. At the end of the lab, zip the whole thing together into a single compressed folder/archive and upload to the Courseworks assignment associated with the practicum. Where audio files are linked in the instructions, you should use your browser to download the file in question.

Download the linked file and open it in Sonic Visualiser. Use the measurement tool in connection with as melodic range spectrogram layer to estimate the names of the first sixteen pitches in the linked recording. Provide your answers in a text file in your folder for this exercise.

Tips:

Listen to this brief excerpt from the 1939 demonstration of the Voder (transcribed below)

- Presenter: For example, Helen, will you have the Voder say, “She saw me”?

- Voder/Helen: She saw me

- Presenter: That sounded awfully flat. How about a little expression? Say the sentence in answer to these questions: Who saw you?

- Voder/Helen: She saw me

- Presenter: Whom did she see?

- Voder/Helen: She saw me

- Presenter: Well, did she see you, or hear you?

- Voder/Helen: She saw me

- Open the file in SV as before

- Add a new spectrogram layer to the default pane

- Add a new time instants layer to the default pane

- Using whatever means you prefer, add five time instants to the recording, one for the presenter’s request, and one for each of the Voder’s responses marked in bold in the transcript above.

Download this wave file in Sonic Visualiser and perform the following tasks:

- Open the file in SV as before

- Create a new time instants layer containing four events corresponding to the downbeat of each measure

- Compute the tempo of the excerpt with the help of a time values layer

- Create another time instants layer in the same pane (use a different color) containing each of the clave hits

Tips:

- Use manual tapping and then use the move tool using the mouse to get the most accurate placement of the time instants

- Use the playback feature on the time instant layers to aurally check the placement of your markers

- Use both the waveform layer and the spectrogram layers to visually check the placement of your markers

File extensions are part of the filename that follow the final .. Some examples of common extensions: .pdf, .gif, .mp3. File extensions are one way that operating systems (e.g. Microsoft Windows, Apple OS) use to record the kind of data being stored by the computer. We know that different programs are suited to opening, representing and manipulating certain kinds of data better than others. Generally speaking, each file extension corresponds to a specific file format. From the technical perspective, file formats standardize the disposition of digital data on the storage medium. They tell computer applications what kind of data to expect, and where it will be laid out on the storage medium in question. For example, most file formats dictate that the first few bytes (one byte is eight bits; one bit is the smallest unit of digital data: either on or off, zero or one) of the file should contain data about the rest of the file: metadata, or data about data. In the case of audio files, these headers can contain important information, such as a record of the sample rate and the bit depth used in the analog-to-digital (ADC) sampling process. If a computer program does not know the original sample rate used during ADC conversion, it may play back the audio file at the wrong rate, leading to something not dissimilar to when an LP is played back at the wrong speed.

Q. What happens if you try to open a

.giffile in a text editor (like Word, Notepad, etc.)? Why do you think that is the case?

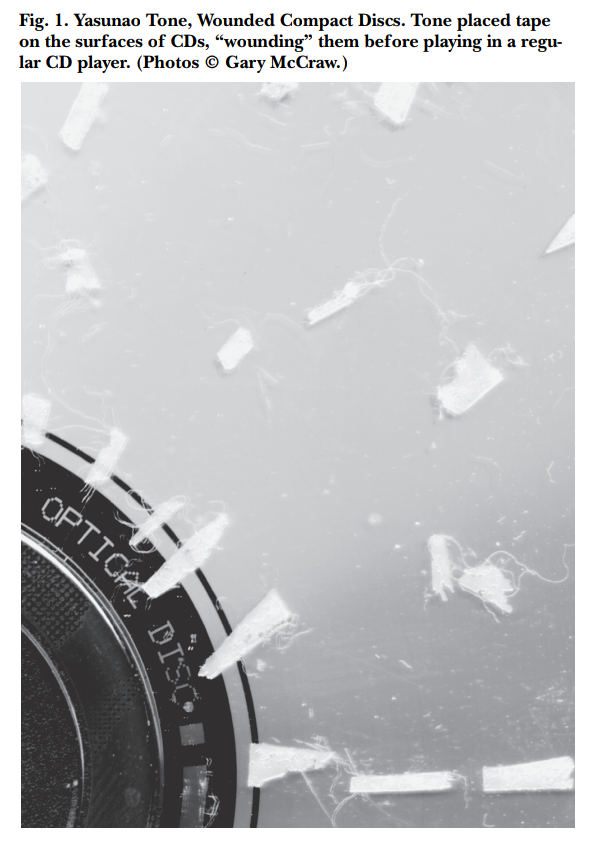

An interesting subgenre of computer art using a technique called databending, creatively misuses applications to edit files in formats that the applications were never intended to manipulate. For example, artists use text editors to introduce “glitches” into image files, by changing the file extension of an image file to .txt, opening the text file in a plain-text editor, corrupting or modifying the text representation of the image and saving the data back as an image file (restoring the original file extension) so that the glitched image can be viewed as before.

Modern multimedia streaming applications (e.g. YouTube or Spotify) will often switch to appropriate formats based on network conditions and device functionality and gracefully degrade the service quality to less bandwidth-hungry formats, as network throughput decreases. The upshot of this is that multimedia streaming platforms, like YouTube, actually store several versions of the same media file, each in a slightly different format. Despite the illusion to the end user that there is only “one” video file corresponding to a single URL (or catalog entry), there are, in fact many different files in diverse formats, each of which has their own technical differences. As we know from Sterne’s perspective, some of these differences are qualitative: they can be percieved as being of greater or lower fidelity; other of these differences are less immediately perceievable but no less important. For example, the licensing rules around particular formats can have an influence on how widely that media can be distributed and consumed. Using an incredibly useful tool (for command-line only, unfortunately) called youtube-dl, we can inspect precisely how many different versions of the “same” video that Google stores for each YouTube URL. The output of running this command on a single URL is included below. You can see the wide range of video and audio formats in use, along with their associated bit rates, total file size, and other information more relevant to video (e.g. image resolution, miscellaneous container information, and frame rate).

[eamonn@iapetus ~]$ youtube-dl -F https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t9QePUT-Yt8

[youtube] t9QePUT-Yt8: Downloading webpage

[youtube] t9QePUT-Yt8: Downloading video info webpage

[info] Available formats for t9QePUT-Yt8:

format code extension resolution note

249 webm audio only DASH audio 54k , opus @ 50k, 934.13KiB

250 webm audio only DASH audio 71k , opus @ 70k, 1.20MiB

171 webm audio only DASH audio 120k , vorbis@128k, 1.96MiB

140 m4a audio only DASH audio 128k , m4a_dash container, mp4a.40.2@128k, 2.37MiB

251 webm audio only DASH audio 142k , opus @160k, 2.38MiB

160 mp4 256x144 144p 108k , avc1.4d400c, 24fps, video only, 1.04MiB

278 webm 256x144 144p 111k , webm container, vp9, 24fps, video only, 1.69MiB

242 webm 426x240 240p 218k , vp9, 24fps, video only, 2.35MiB

133 mp4 426x240 240p 240k , avc1.4d4015, 24fps, video only, 2.11MiB

243 webm 640x360 360p 402k , vp9, 24fps, video only, 4.72MiB

134 mp4 640x360 360p 584k , avc1.4d401e, 24fps, video only, 4.33MiB

244 webm 854x480 480p 731k , vp9, 24fps, video only, 7.81MiB

135 mp4 854x480 480p 1245k , avc1.4d401e, 24fps, video only, 9.02MiB

247 webm 1280x720 720p 1509k , vp9, 24fps, video only, 11.79MiB

136 mp4 1280x720 720p 1989k , avc1.4d401f, 24fps, video only, 14.03MiB

248 webm 1920x1080 1080p 2642k , vp9, 24fps, video only, 19.08MiB

137 mp4 1920x1080 1080p 3167k , avc1.640028, 24fps, video only, 22.42MiB

17 3gp 176x144 small , mp4v.20.3, mp4a.40.2@ 24k, 1.53MiB

36 3gp 320x180 small , mp4v.20.3, mp4a.40.2, 4.22MiB

18 mp4 640x360 medium , avc1.42001E, mp4a.40.2@ 96k, 8.49MiB

43 webm 640x360 medium , vp8.0, vorbis@128k, 12.74MiB

22 mp4 1280x720 hd720 , avc1.64001F, mp4a.40.2@192k (best)

Of the digital audio files, here are some of the more commonly encountered file extensions and the formats that they denote:

.wav- Wave file.mp3- MPEG Layer 3 Audio File.aac- Advanced Audio Coding (.m4aalso used sometimes, especially by Apple).m4p- Like an.aacfile, but copy-protected with DRM features.flac- Free Lossless Audio Codec.ogg- Ogg Vorbis/Theora

Wave files (.wav extension) are the most straightforward file format in this list, essentially consisting of a sequence of raw intensity values that are the results of the process of digital sampling. As a result, a wave file can be used to faithfully reconstruct the entire original audio signal within the human hearing range without any actual loss. Digital audio files stored in this format are rather large: approximately 10.09 MB per minute of recorded sound. Considering that the theoretical maximum download speed of most dial-up internet connections during the 1990s was 28.8 kbps (0.0036 MB/s), it would take at least 2.5 hours to download a single ~3-minute track stored in this format. The online distribution of music required either smaller file sizes, or faster internet connections.

We can easily reduce the size of the resulting wave file if we decrease the sample rate: a lower sample rate means fewer samples per second, and for a fixed track length this will result in fewer samples and hence a smaller file size. In fact, the wave file format allows for number of different sample rates. Here are recordings of the same audio source, in .wav format, at a number of different sample rates:

- audio/sr-example.wav

- audio/sr-example22050.wav

- audio/sr-example11025.wav

- audio/sr-example8000.wav

- audio/sr-example4000.wav

As the sample rate decreases, the audio source becomes less intelligible as unwanted distortions of the original sound are introduced. These downsampling artifacts become worse as the Nyquist frequency—the maximum reproducible frequency given a sample rate—falls below the limit of the high frequency (high-pitched) components in the original recording.

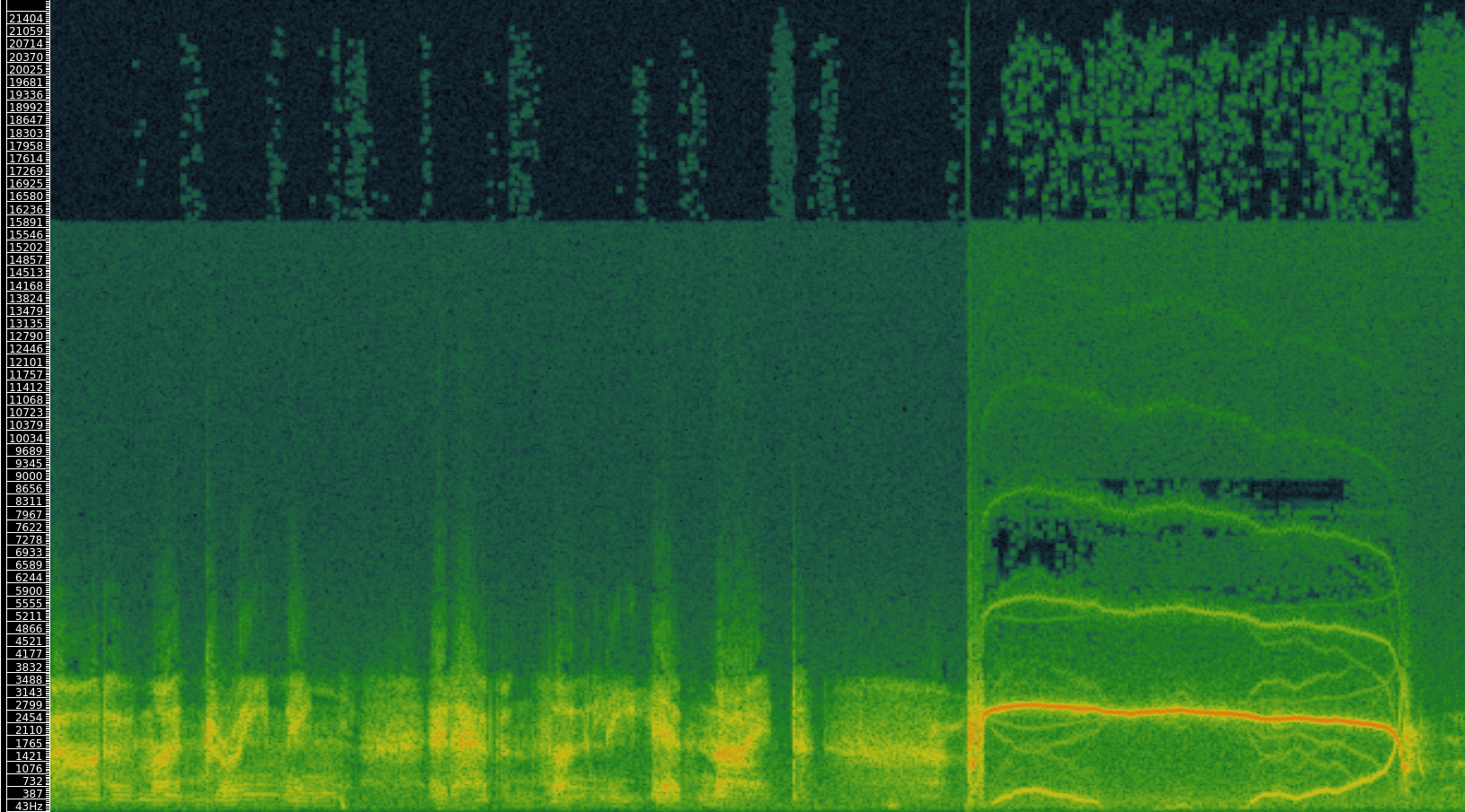

Shown here is a spectrogram depicting a short excerpt from a radio play by Gregory Whitehead, Pressures of the Unspeakable (1991), which uses as its source material recordings made from a telephone number that he set up to record callers’ screams on behalf of the fictitious “Institute for Screamscape Studies”. In the first three quarters of this excerpt, a child phones in and (finally) screams loudly into the telephone at around 2.5 kHz (the big band of spectral energy). We can see that the telephone format is pretty narrowly bandlimited—there is much less spectral energy above 3.5 kHz, at a filter cutoff point. Another filter cutoff is visible around 15 kHz, probably due to another lossy compression pass.

The more interesting artifacts are in the scream portion, where an effect of the low sampling rate of the telephone format can be detected. The “mirror” images of the central scream band that are scattered throughout the lower fifth of the spectrum are the result of a phenomenon called “folding”, which takes place when spectral content that exceeds the Nyquist frequency (determined by the sampling rate) is indistinguishable from a shifted version of that signal. For more, see here.

Q. What audio applications might be suited the use of downsampling as a means of reducing file size? What aspects of such an application determine the minimum acceptable sample rate?

For music, then, lower sample rates (as used in telephony) are not an especially desirable solution to the problem of large digital audio files in .wav format.

The task of reducing the file size of a digital file on disk while preserving its content is called compression. The word “compression” is also used in an audio processing context to describe something else; we will only use the term compression in the above sense. In this section we consider perhaps the most (in)famous audio compression algorithm: MP3. Compression algorithms can be lossless or lossy.

Lossless compression algorithms take advantage of statistical properties of the stored data to reduce the size of the audio file. When the compression process is reversed, the source file can be recovered exactly. We will not touch on lossless audio compression algorithms (e.g. FLAC, ALAC, APE) any further except to point out that lossless in this context doesn’t mean apparently or perceptually “lossless” but actually lossless from a statistical perspective: the original audio source is identical to the decompressed file. Many widely used lossless compression algorithms make used of a dictionary-based approach to compression; this worked example shows how one such algorithm works, at least in principle.

Lossy compression algorithms reduce the amount of information in the original wave file, and so a sample-by-sample exact copy of the original audio file cannot be recovered after lossy compression. However, lossy compression algorithms often make use of the limits of human perception to reduce the information content of a digital file in such a way as to make the compressed version perceptually indistinguishable from the original. MP3 (MPEG Layer 3) is one such algorithm.

In the last lab, we made use of SV’s “layers” functionality to overlay various kinds of data (time instants, time values, spectral analyses…) over a single audio recording. In this lab, we will use SV’s “panes” to simultaneously analyze two related recordings. Using this feature allows us to make direct comparisons between the content of two or more audio files. This is useful for:

- Determining the relative quality of digital audio files

- Understanding the audible differences between two recordings dating from different time periods or transmission channels

- Studying early versions and covers of songs

- Studying arrangements or transcriptions of instrumental works

- Comparing expressive performance interpretations (such as tempo rubato and dynamic changes) between different renditions of the same work

In a SV session with one open file, you can add additional audio files using File > Import More Audio.... You can add more than two files, if you like, but the screen gets a little crowded. Each pane will have its own set of layers associated with it, which can be edited separately. Note, at this point, now that there are two audio files loaded in the SV session, that adding a new layer based on audio content (e.g. a spectrogram layer) will require you to specify the audio file from which the data should be drawn. Take care to add layers to their “correct” pane.

SV also supports the automatic alignment of multiple recordings of based on pitch and rhythm content. This especially useful for comparing recordings of the same piece. Before you begin, you must ensure that the Match VAMP plugin is installed. If it is correctly installed, you will see the “Align File Timelines” button in the toolbar as indicated in the screenshot below.

When aligning files, one pane must be selected to be the reference recording for the alignment: the playhead for this pane will advance as usual during playback; the playhead will skip around the aligned recording as needed to maintain the synchronization between the parts. To execute the alignment:

- Ensure that the pane that you wish to designate as the reference recording is active. In the screenshot, the black band indicates the active pane (the top)

- Click the “Align File Timelines” button

- Wait for alignment to complete

Once the files are aligned, you can playback the recordings and switch between audition of the reference recording and the align recording with ease. Clicking the “Solo” button (the “S” in the toolbar beside the alignment icon) will cause playback in inactive panes to mute.

Another advantage of alignment is that any time instants that have been added to a layer associated with the reference recording can be copied from the reference recording to the aligned recording and the positions of the time instants relative to the content of the audio content will be preserved. For example, this allows us to provide beat-level annotations on the reference recording of a piece of music using time instants and copy them to a different version of the same piece of music—say, the same score performed by a different performer—in which the timing of the events do not precisely correspond.

Make sure that you have installed the MATCH VAMP plugin before you attempt these exercises.

Download these two audio files:

- Open up the two files in two separate panes (inside the same SV session file) as described in the lab notebook above.

- Add (full-range) spectrogram layers to each pane.

- One of these files is an MP3 compressed version of the other. List all possible sources of evidence you can draw on to make this conclusion.

Download these two audio files:

- R.E.M. - Photograph (Demo) (released in 2017 with the anniversary reissue of Automatic for the People)

- R.E.M. and Natalie Merchant - Photograph (released 1993 on Born to Choose)

Load these two files into separate panes in SV, and using the Match plugin and the “Solo” button, listen a couple of times to each version and, using time instants in the appropriate places, label five diff erences between the versions that you notice. The differences can be very obvious!

This exercise draws on the skills learned in the last lab as well as today’s. Your goal is to derive two tempo curves for two different performances of the first eight measures of a piano composition (Op. 17, No. 1) by Chopin.

Download the recordings here:

Here is a score, for reference (notice that there’s an upbeat/anacrusis)

You will need to:

- Load both recordings into separate panes

- Align them using the MATCH plugin

- Add time instant layers on every beat of each measure (ask if unsure) to the top pane (Reference)

- Make sure there are no erroneous duplicate instants

- Number the time instants using a cyclic counter appropriate to the meter of the recording (triple meter)

- Aurally verify the placement of the time instants in the reference recording

- Copy the time instant layers from the top pane to the bottom pane (accept the proposed realignment)

- Aurally verify the placement of the time instants in the aligned recording (some may be incorrect)

- Create time value layers for each pane showing the tempo change over time for each recording

As a bonus, you can export the data from the time value layers and create a pretty line graph showing both tempo measurements on the same graph using Excel or similar. (Not for credit)

Facebook offers the most ready-to-hand example of a social network online: people enter into reciprocal relationships online (“friendship”); your choice of friends determine the content you see, the interactions that are permitted on the platform, and so on. In turn, the choices of your friends determine the content that they see, which might include content you have produced or uploaded to the network. In this way, information can pass from you to an effective stranger, via mutual friends. The structure of the network determines the reach of your posts—-and the flow of your personal data.

We can keep a track of these relationships in a list of friendships:

- Schmidt is friends with Haas

- Hofmann is friends with Haas

- Haas is friends with Fritzsche

- Schmidt is friends with Fritzsche

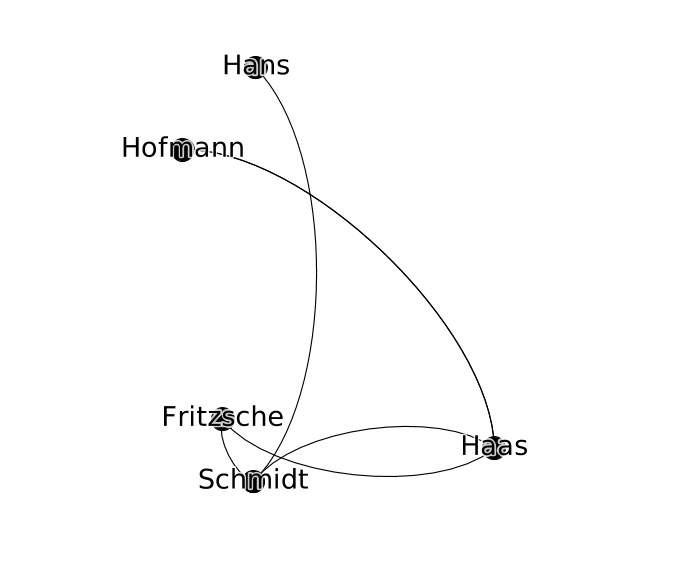

To better keep track of how this information—status updates, photos, rumors, consumer preferences—might circulate in this network, we can start to visualize it in a diagram that records both users and their friendship relations, drawing users as nodes and connecting any users who are friends with lines (or edges). This abstract represntation of the network is called a graph.

The advantage of this approach is that it is highly general: we can analyze networks of all kinds, not just social networks. In the particular case of the production and distribution of music, I have had interesting results using graphs to study some of the the following phenomena:

- nodes represent performers in the New York Philharmonic; edges connect performers who have performed together in concert

- nodes represent computers; edges connect computers which are linked together in a file-sharing network

- nodes represent music theory treatises in Latin; edges connect theory treatises that cite each other (close to verbatim citation; determined using text similarity measurments)

Graphs have also been used in the following way:

- nodes represent words; edges represent lexical relationships (e.g. synonyms, antonym, hypernyms) [WordNet]

- nodes represent concepts in music performance; edges represent dependency relations between these concepts (e.g. a performance of score is viewed as an instantiation of a musical work)

- nodes represent events in a musical score; edges represent music-theoretical dependencies between them (defined in the analytical literature)

It can also be used as the basis for quantiative analyses of the graph to investigate features of the network in reality that emerge from its connective structure.

A graph can be described simply as collection of nodes and a collection of edges. The nodes in a graph are the “things” of the network. Nodes can represent anything: people, concepts, computers. In all the examples in this session, nodes represent people. Edges in the network connect the “things” of a network. An edge is drawn between exactly two nodes. The presence of an edge represents some dyadic relation between nodes; in this session, they will always represent a social relationship between two people.

Rewriting the table above as a set of nodes and edges, we get the following:

Nodes (people):

- Fritzsche

- Schmidt

- Hofmann

- Hans

- Haas

Edges (relationships):

- Schmidt <-> Haas

- Hofmann <-> Haas

- Haas <-> Fritzsche

- Schmidt <-> Fritzsche

- Hans <-> Schmidt

- Hofmann <-> Haas

Q. In this case it is possible to describe the graph completely by just looking at the edge data. Why? In what circumstances is the edge data not enough to describe the graph completely?

This where the tool Gephi comes in. Gephi is an open-source, cross-platform software package for loading, creating, and editing graphs as well as preparing them for publication. Gephi allows us to move from a tabular representation of the structure of the graph (which lists the nodes and the edges as above) to an interactive visual representation. Gephi can be used to construct a graph from scratch or to open up a pre-existing dataset for analysis or visualization.

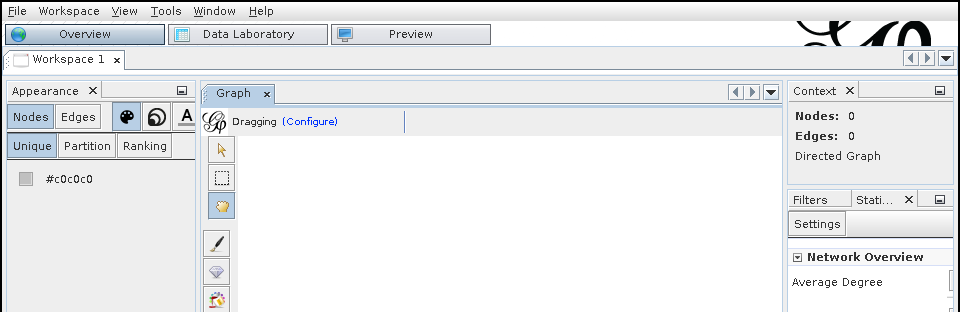

Upon opening Gephi for the first time, you’ll be greeted with a splash screen: choose “New Project”, which will create an empty workspace. Each project can contain multiple workspaces, similar to a tabs in a web browser. We will only work with one workspace at a time. Not unlike Sonic Visualizer, there are three different views on the same workspace:

- Overview

- Data Laboratory

- Preview

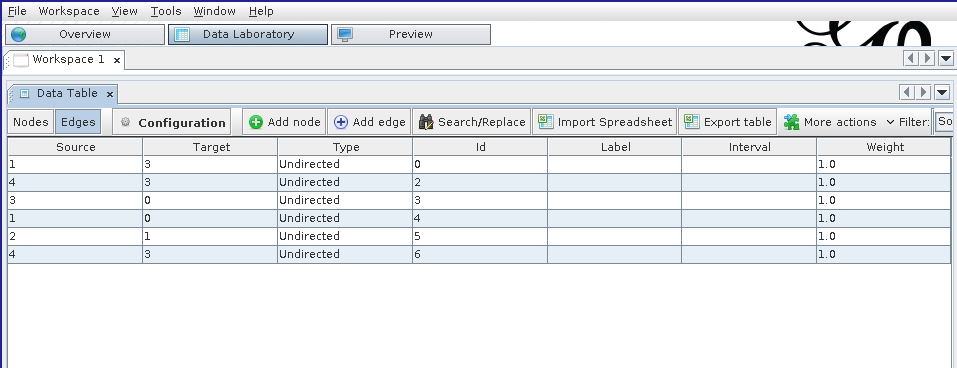

The Data Laboratory is a view of the graph being described in terms of nodes and edges, resembling a spreadsheet tool like Excel. It shows the underlying data that is used to generate the visualization. Within the Data Laboratory view, Nodes and Edges are represented in separate tables. To start building a graph, navigate to the Nodes spreadsheet and click “Add Node”. A dialog box will prompt you to add in a label for the node, which will be associated with the new node and should be memorable and/or descriptive. (It doesn’t have to be unique, but it helps when starting out). Adding the node adds a line to the “Nodes” table; the Id column gives a unique Id for the node in question—this is separate from the label.

To add an edge between two nodes, click the “Edges” button (beneath the “Data Table” tab). A dialog box will pop up. The most important fields are the source and the target node, which define the edge: the existence of a relation between two nodes. The next most important attribute is whether the edge is directed or undirected (the radio button). The correct choice for this will be discussed below, and depends on what you want your graph to capture.

In modeling the German social group above, we can assume that all friendships are reciprocal (as they are on Facebook—a notable divergence from reality). Necessarily reciprocal social relationships are well reflected by creating undirected edges between notes. The “Edge kind” property can be used to keep track of multiple kinds of relations between nodes (e.g. interpersonal relationship by marriage, by descent, by adoption, etc.) where such a distinction is important.

The Overview provides a view of the graph that is most useful for analyzing the structure of the graph, styling the graph based on its properties, and laying out the graph.

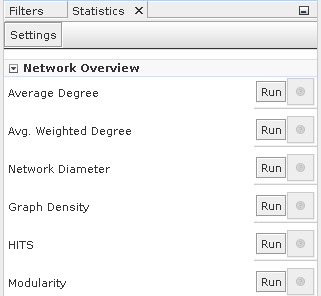

Analyzing the structure of the graph

This panel can be used to compute summary statistics that characterize the graph as whole,

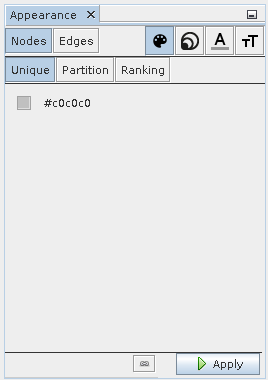

Styling the graph

Once the statistics have been computed in the analysis panel on the right-hand side, they can be integrated into the visualization so that the styling of the graph reflects some of the computed statistics. In this way, the plain node–edges view of the graph can be enriched with extra information about the relative importance of the nodes, edges, and their relations.

The four icons in the top right correspond to the visual features that can be changed. In order, they are:

- color

- size

- label color

- label size

These can be tweaked for both nodes and edges and can draw on continuous statistics about the graph or categorical data. To change the size of a node to reflect the size of a statistic associated with it, select the size icon and the ranking tab.

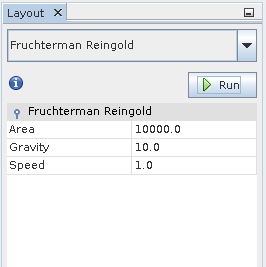

Graph layout

Finally, the graph layout can be modified automatically by the application of a number of layout algorithms, which distribute the nodes around the workspace according to different criteria. We can modify the layout by hand in the main “Graph” pane, but this quickly becomes tedious for anything but the smallest of graphs.

Some of the layout algorithms are basic (contract/expand), naive (random layout), or more complicated (Force Atlas). Each algorithm aims to reveal different latent structures in the graph—sometimes preserving or calling attention to communities.

Many of the layout algorithms will continue running without stopping, even when they have reached the optimum layout, and in this case it is important to remember to stop the layout algorithm before continuing to manipulate the graph.

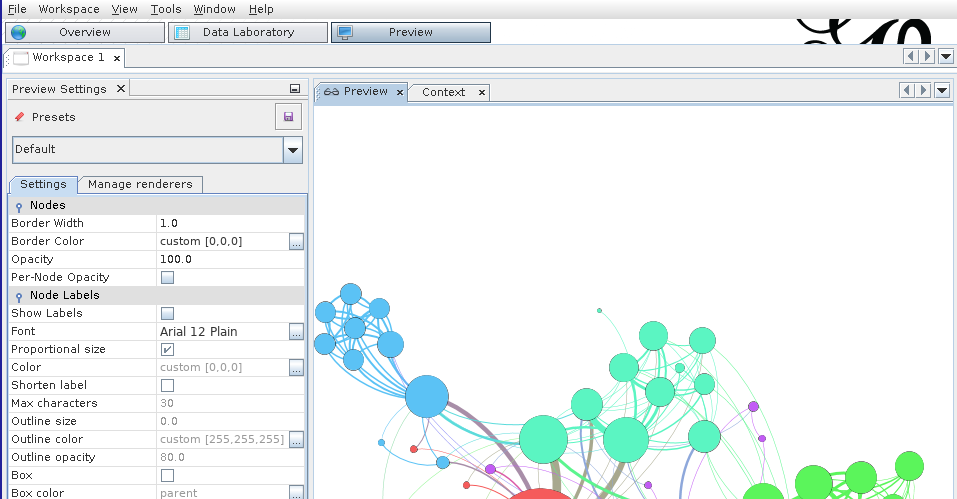

The Preview shows a view of the graph that is closest to how it might appear in publication or in print. Most of the changes that can be made to the graph in the preview pane are cosemetic, including decisions like line weight, font weight, the style of node labels or edge labels, etc. You might have to click the “Refresh” button (in the left-hand panel) to force the Preview to redraw itself.

The styling options here are of general application to all graph visualizations, unlike those in the Overview view. Here, styling decisions can improve the readability of the graph and make it easier to interpret. The biggest limitation of Gephi’s styling in this view is the lack of support for nudging labels away from the nodes or edges to which they are attached.

The social network for which our graph serves as a model or visualization may have certain particular structures that we should reflect in the graph. For instance, the “friend of” relationship on Facebook is reciprocal: although a user can unilaterally invite someone to be their friend, ultimately the relationship does not exist until both parties accept. Consequently, person A is friends with B, just as B is friends with A: the “is friends with” relationship is reciprocal (we might say symmetrical). The case is different on Twitter. User A may follow User B without user B following user A. The “is follower of” relationship is not reciprocal. A graph that keeps track of non-reciprocal, “is follower of”-type relations is called a directed graph. Edges in a directed graph are said to be directed.

The degree of a node measures how many other nodes that are immediately connected to it (i.e. direct neighbors via edges).

If the graph is directed—i.e. you distinguish between outgoing and ingoing edges—then there are two degree statistics that can be computed for each node:

- indegree: the number of inward directed graph edges that impinge on a given node

- outdegree: the number of outward directed graph edges that radiate from a given node

Depending on the details of the network being modeled in the graph, the degree statistic has a different interpretation. For example, in the reciprocal social network example, node degree is the number of friends that the connection represented by the node has.

Gephi uses a proprietary format for storing its graph visualizations, which ends with the .gexf extension. If you are simply saving your work for future use with Gephi, or planning to share it with other users of Gephi, this format is the best choice. It preserves many of the layout, styling, and analysis results, such that when the file is re-opened, the user can continue working on the visualization starting precisely from the place they last started off.

The downside of the .gexf format is that it is not widely supported by other graph editing, visualization, and analysis tools. As with digital audio files, there are a number of different formats for storing graph data. Some of the formats supported by Gephi include:

- GDF files

- GraphML files

- NET (Pajek) files

These files generally store the entire structure of the graph: both the nodes and edges, as well as (depending on the format) layout and statistical features. Pre-existing datasets may or may not be available in the above formats. It is important to be familiar with the most basic way of representing graph data, which we deal with below.

Since a graph can basicially defined by a list of edges and nodes, Gephi also supports the export of graph data into a basic spreadsheet-like “format” called CSV (.csv extension). CSV is a pretty basic format, supporting only one table at a time, so to fully describe the graph will require you to export two separate files: the node table, and the edge table. These correspond to the data in the two views available in the Data Laboratory. The advantage of a CSV file is that it can be opened on almost all platforms, independent of what application you have available for graph analysis.

- Click

File > Export > Graph file... - Under

Files of Type, choose “Spreadsheet Files (*.csv *.tsv)” (not “CSV Files”) - Click

Options... - Ensure that the “Table” type is set to

Nodes - Choose a filename for the node data

- Click

Save - Repeat steps 1. through 6. changing the table type to

Edgesand changing the filename so as not to overwrite the node data.

To load an existing dataset into Gephi, you can directly load .gexf file using the File > Open... dialog.

In the case where the dataset is stored in a .csv format, it’s more straighforward to create a new workspace and navigate to the Data Laboratory view. There, you can click “Import Spreadsheet” and import .csv files for the node and edge data separately.

- Use Gephi to make a graph of your own social network (e.g. friends or family, or both). Use initials or made-up names if you prefer, but you should try to input relationship data with which you are familiar with. Your network should include at least 5 nodes, and at least 10 edges. You do not need to use edge types to qualify the nature of the relationships.

- Export this data to two

.csvfiles, one for the node data, and the other for the edges. - Save your work in Gephi in a

.gexffile and submit these three files together.

Tips:

- Use nodes to represent individuals.

- Use undirected edges to represent the existence of a reciprocal relationship (friendship, familial or otherwise) between individuals.

In this exercise you will work with one of the oldest social network datasets published in sociological literature, the Class of 1880⁄81 dataset. It describes a friendship network in a school class using a directed graph.

The data was transcribed from the original article and subjected to new analyses in a recent paper: Heidler, R., Gamper, M., Herz, A., Eßer, F. (2014), Relationship patterns in the 19th century: The friendship network in a German boys’ school class from 1880 to 1881 revisited. Social Networks 13: 1-13.

- Download and open the dataset in Gephi.

- Determine the average degree for the network using the statistics tool.

- Style the graph such that:

- the size of each node reflects its in-degree of the node

- the color of the node reflects the out-degree of the node

This week we move on from a basic introduction to the graph formalism, with its abstract notions of node and networks toward using Gephi to reveal interesting (or disinteresting) structures that might be latent inside a particular networked dataset. In this lab, we will learn how the various different layout algorithms available in Gephi emphasize different structural characteristics of the graph, get a better understanding of measures of centrality, and briefly examine how Gephi’s community detection algorithm can be used to isolate subgraphs of the larger dataset that might be worth looking into further.

As you hopefully understood from preparing for Monday’s class, empirical methods for examining cultural datasets do not always provide us with explanations for why the data has the structure that a researcher has isolated using the tools at their disposal. The researcher has to formulate their own hypotheses for why the data has the structure in question. When it comes to using graphs, the hypothesis that are available to the researcher usually make use of arguments about how the netwoork that the graph models is organized. Some suggestive questions include:

- Is any one node more important than all the others? If so, why might this be the case? Does this explanation invoke a specific charactersitic of this particular network, or is it a general feature of networks of this kind?

- Do nodes that are a priori known to be more important than others—perhaps determined by some other dataset e.g. the number of weeks that the person corresponding to the node had an album in the Billboard Top 40 in a given year—have a privileged position in the graph? Are they highly connected?

- Do the various different ways of measuring centrality affect the answers to these questions, and if so, how can your particular choice of centrality measure(s) be justified by appealing to the particular domain you are studying as well as the features of the measure?

The social network for which our graph serves as a model or visualization may have certain particular features that we should reflect in the graph. For instance, the “friend of” relationship on Facebook is reciprocal: although a user can unilaterally invite someone to be their friend, ultimately the relationship does not exist until both parties accept. Consequently, person A is friends with B, just as B is friends with A: the “is friends with” relationship is reciprocal (we might say symmetrical). The case is different on Twitter. User A may follow User B without user B following user A. The “is follower of” relationship is not reciprocal. A graph that keeps track of non-reciprocal, “is follower of”-type relations is called a directed graph. Edges in a directed graph are said to be directed.

Another useful distinction to make is between continuous and categorical data. Continuous data can usually be expressed as a quantity, such as height, age, weight, node degree, centrality, etc. Categorical data is not immediately understandable as a quantity, for example: gender, group membership, highest level of educational attainment, nationality, etc. Some node properties are continuous data (e.g. in-degree), while other node properties are categorical (e.g. cluster membership).

Once you have computed this data for the graph you are studying, you might want to use Gephi to visualize this information. In the last lab, we looked at how to change the node size and color in to reflect the value of a continuous data point: degree. Using color to visualize continuous data can be useful, but must be handled with care: a not-insignificant proportion of the population experience a color vision deficiency of some kind or another, and even those with “perfect” color vision can not always tell the difference between two closely-related color intensities. Size is generally more comprehensible to the viewer for continuous data.

However, color can still be used judiciously, especially to reflect categorical data. In this case, different node colors will represnt the membership of that node in a particular group. Try and avoid color cliches in assigning colors to categorical values (e.g. blue vs. pink for male/female) but also, if there is an accepted technical convention in place (e.g. blue for cold water and red for hot water), then it should either be used without modification or completely ignored—and definitely not inverted!

In this section, we review the four centrality measures that were used in Topirceanu et al. (2014), in order to understand the differences between them, and the circumstance under which one may be more useful to your project. It’s important to remember two things. First, centrality, on its own, is an abstract concept about graphs. It is a mathematical feature of a model of reality, not an attribute of the real network we are using the graph to describe. I have tried to remain terminologically consistent in this regard: I use the word “network” to refer to the actual thing we’re studying (be it publication links, collaborations in the music industry, or features of a live collaborative musical performance), whereas I use the word “graph” to refer to the abstract version of that phenomenon, which we are manipulating, computing statistics on, and visualizing with the help of Gephi.

Unfortunately, the word “centrality” conjures up all sorts of associations with notions of influence and importance, which themselves may vary in meaning depending on context. The social mechanisms that an influential composer uses to leverage the publication networks of the 16th century are different to those that a record producer uses in the 21st century. They may very well be similar enough to justify using the same centrality measure to capture and describe their influence, but this is not a given.

Relatedly, and secondly, this means that centrality is not necessarily—by itself—a measure of influence. To a humanist, influence may be understood to work in manifold ways, none mutually exclusive: direct contact between individuals can explain the existence of a shared idea, but there is no guarantee that it can be attributed to a particular social interaction. Ideas or information can be stored in media (books, online) and retrieved later without any direct social contact; ideas are sometimes said to be “in the air” or part of a larger Zeitgeist in which a set of values or ideals are shared by the public; information can also come from non-individual social actors i.e. institutions such as the univeristy or the press (free or otherwise). The most straightforward way of modeling social or cultural influence using a graph is to think about units of cultural exchance and replication (memes, in the original sense coined by Dawkins et al., or “culturemes”) that pass along the edges of the graph, the propagation of which through the network (diffusion) is accelerated by well-connected or more central nodes, and impeded by less well-connected nodes.

This discussion draws heavily on exposition of these concepts in the material posted here.

Degree centrality uses the number of immediate connections a node has as a to capture the centrality of the node. The basic assumption behind degree centrality is that “central nodes have lots of neighbors”. It is straightforward to see how this way of measuring centrality may fail to capture the importance of nodes involved in certain structures.

Consider the example of the personal assistant to the CEO of a large corporation. The CEO is connected to the other members of the executive board, who themselves are well-connected to the rest of the company. The PA, at least according to the organizational chart in this hypothetical example, is only connected to the CEO and has degree 1. They would not be considered particularly central by this measure, despite their ability to make an impact on the decisions of the CEO, whose ideas will, in turn, cascade through the rest of the organization, according to the network structure.

Eigenvector centrality is a way to improve the measurement of node centrality by taking a global view of the connectivity of the graph into consideration when computing the statistic for each graph. The mathematical details needn’t detain us but, in brief, the structure of a graph can be written down as matrix in which cells are filled with 0 or 1 depending on the edge structure of the graph. Then, because adjacency matrices for most of the graphs we are interested in have a predictable structure, we can compute a set of unique and postive vectors out of this this matrix (called eigenvectors) and use their components as centrality measures for each node.

Probably the least intuitive to grasp, but nevertheless works well to capture the notion that “a node is central if it is linked to by other central nodes”. Importantly, it allows for nodes like that for the hypothetical PA: those that have low degree but those connections are to important nodes.

PageRank is a centrality measure described by Page et. al (1999) in a classic paper as and infamously used in the early days of Google to evaluate the relative importance of Web pages, so that responsive search results could be ranked according to their usefulness as measured not only by this statistic but by other content-based features as well.

PageRank takes the following three features of the graph into consideration in computing a given node’s centrality:

- the number of inbound connections into that node

- how likely the inbound connectors are to connect with another node (propensity)

- the PageRank of the inbound connectors

The first factor reflects the natural principle that underpins the more naive degree centrality measure described above. The second factor holds that the value of links from a given node “depreciate” in value the more connections that node has. The third factor assumes that links from high-quality nodes are themselves more useful. The fact that the PageRank uses PageRank in its own definition (a kind of self-dependency) means that this quantity has to be calculated and updated iteratively. One of the significant technical achievements of Google was that they were able to implement such a calculation of PageRank and other related statistics at scale, and keep these statistics fresh as the size of the Web grew explosively.

In some ways, betweeness centrality is the least like the other centrality measures described here.

A vertex can have quite low degree, be connected to others that have low degree, even be a long way from others on average, and still have high betweenness.

This is because betweeness centrality is high when a node is likely to be on the path between other vertices. A node with high betweeness centrality is likely to mediate communications between any given pair of nodes. If the graph models a power network, or another information-passing situation, then nodes with high betweeness are the most critical: if removed, they will have the most impact on the performance of the network. In the social network context, people with high betweenness centrality may not necessarily themselves be highly connected (i.e. have high degree) but serve, nevertheless, as the point of mutual friendship between a large number of individuals.

If you are preparing a Gephi visualization for publication, you should make your final adjustments in the Preview view mode and then click the export button in the bottom left. Choose a vectorized image format (.svg or .pdf). It will allow you or a publisher to scale up or down the visualization to arbitrary sizes without loss of resolution or definition.

To estimate the existence of coherent communities (or subgraphs) within the larger dataset, use the Modularity statistic and color the nodes according to the categorical data that it generates.

- Using Gephi, compute the eigenvector centrality for each node and style the node size to reflect its eigenvector centrality.

- Then, for each of the following layout algorithms, run the algorithm and export a

.pngimage with node labels (you can use No-overlap + Label Adjust immediately afterwards to make them more readable) for each layout:- Random Layout

- ForceAtlas 2

- Yifan Hu

- Fructerman Reingold

- Based on your understanding of what eigenvector centrality means and your intuitions about how childhood friendship groups are formed and structured, what are the most and least useful layouts for revealing the social dynamics of the classroom. How does the layout choice shift your focus while viewing the visualization? What kinds of structures does it emphasize? What kinds of structures are harder to see?

Write your answers in a short .txt file and include it along with the .png images in your submission.

Your goal is to explore the relationships between performers in a network dataset that has been abstracted from the historical performance records of the New York Philharmonic.

The dataset can be downloaded from here. It’s an edges file, so you’ll have to import it into the Data Laboratory view. When the file is imported, you’ll notice the names of the performers have been added as node Ids but not as labels. Use the “Copy data to other column” feature at the bottom of the spreadsheet to copy the node Ids to the label column. The original XML files from which the dataset was derived are available on GitHub.

A short (200-300 word) text file should accompany a visualization (or set of visualizations) created in Gephi that together are designed to:

- identify by name and profession (use the Google) three “central” performers in the network

- identify and characterize the structure of one or two distinct communities of performers within the group

- provide hypotheses (historical or statistical) for why these “central” performers and/or communities exist in the data

You should also make use of the New York Philarmonic’s interface to their Performance History dataset online to help you formulate any historical arguments about the data.

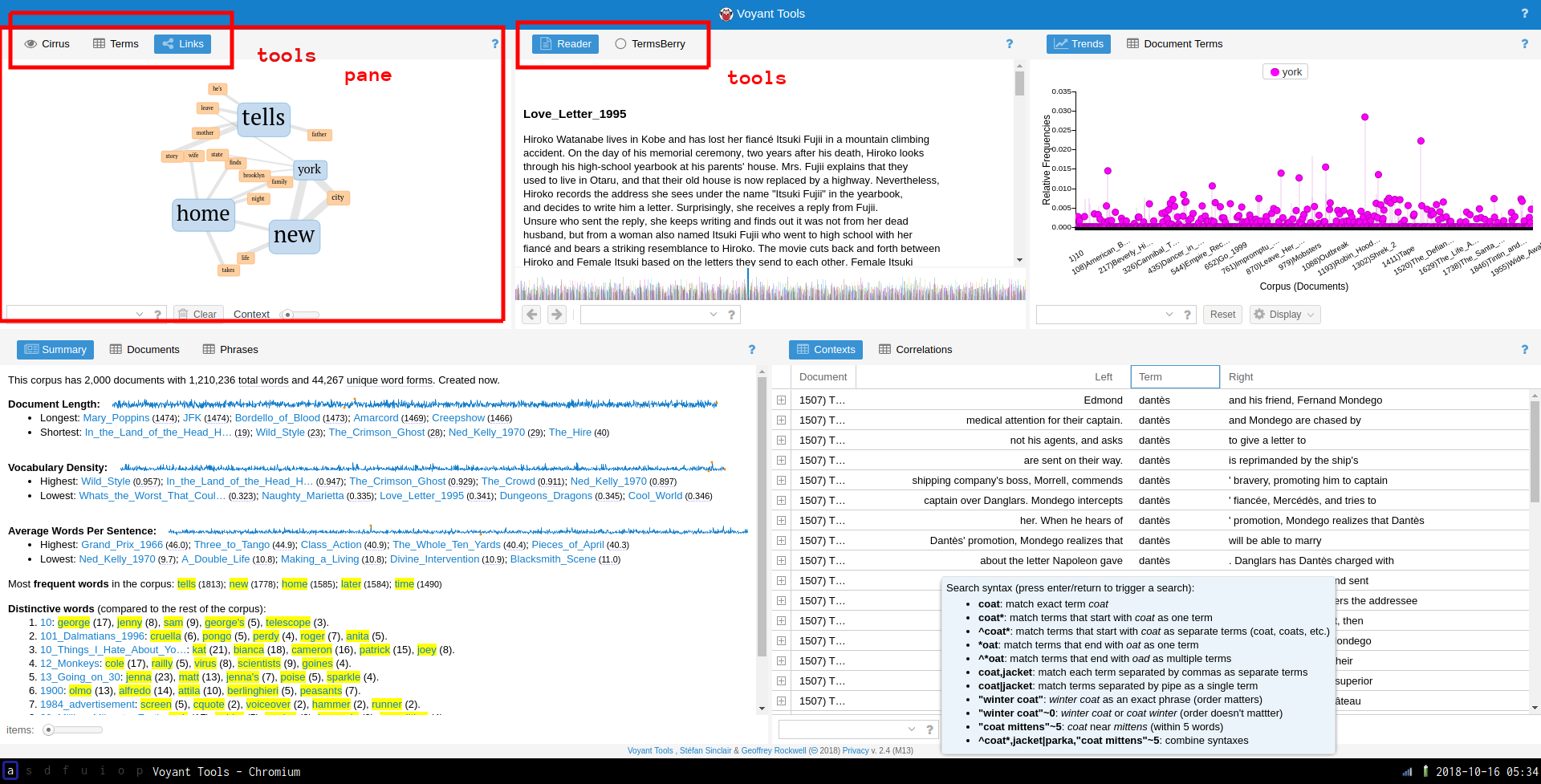

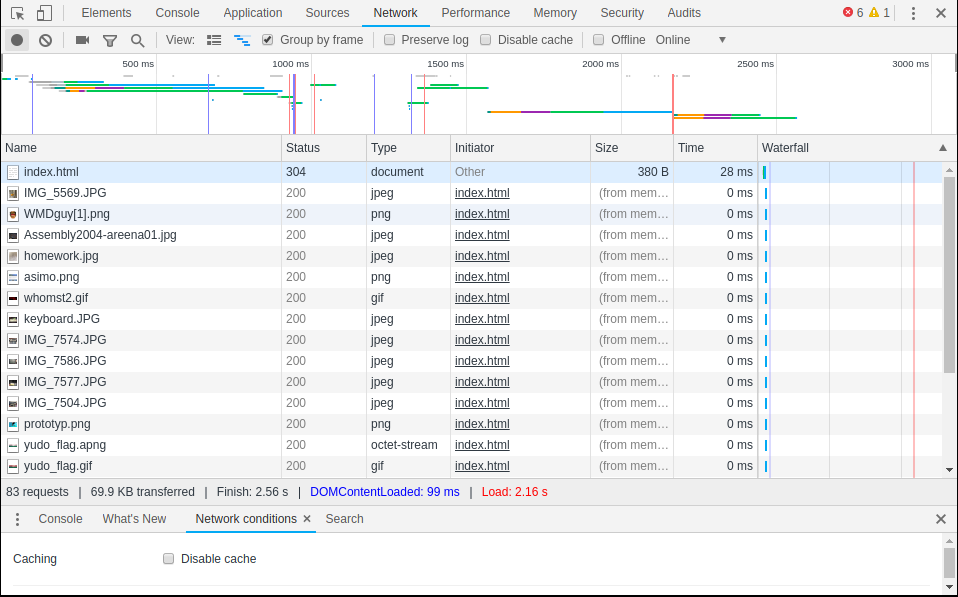

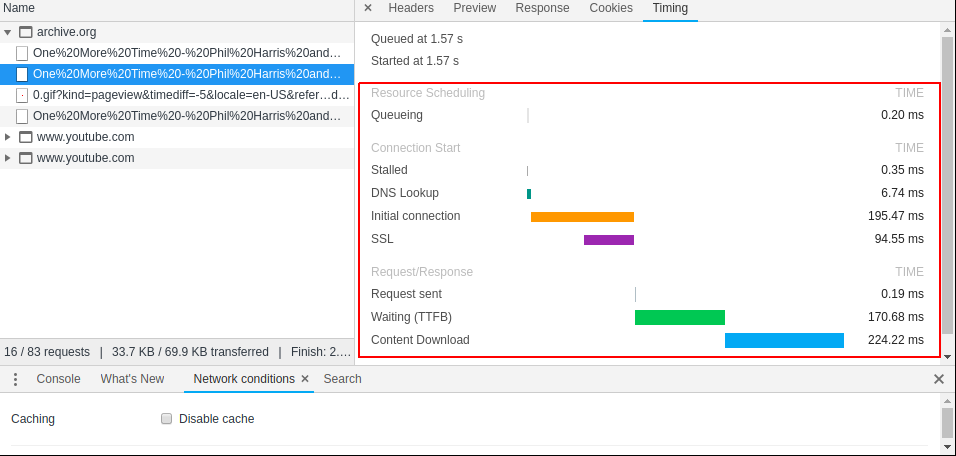

In this notebook it will probably be useful to right click on the screenshot images to view them in full size (or to use the zoom feature on your browser)

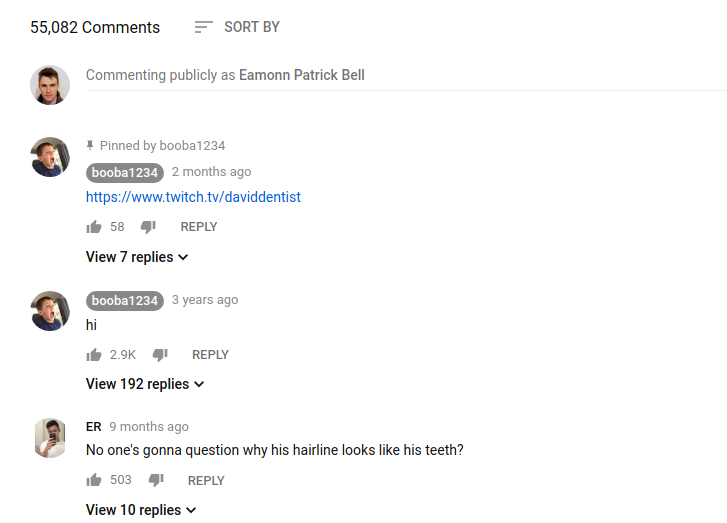

Although the web is a multimedia phenomenon, the document object model (DOM) that acts as the scaffold for every website you view reflects, at heart, a standard for marking up text: words. Inestimable billions of characters of text are transferred across the internet in thousands of languages. Some texts are read more widely than others: a popular news story on the front page of the New York Times website could reach many orders of magnitude more people than a comment buried deep in the bowels of a specialist forum, perhaps gated by a password or a sign-up form. Sometimes, the reach of seemingly marginal texts gets amplified by network effects, as writtent content goes “viral”. Viral texts are reproduced, by copy-paste, by reposting or retweeting, by straight-up plagiarism, or by paraphrase.

It is comonly asserted that the web is a social space, which is certainly true in and of itself. But communities can form for a variety of different reasons, and many of these processes happen simultaneously online. Community-building may have many premises: around a common interest, a common geographic location, a common demographic. There are technological bases that can be used to engineer these communities into existence, for better or worse: surveys/questionnaires, location services APIs (e.g. GPS on a smartphone), financial data brokers. Sometimes all these abovementioned technologies can be used in consort, as in, for example, dating apps or fully ramified social networks like Facebook.

nother way to establish the existence of these commonalities is the creation of communities around texts, in which the comment interest finds its expression. As users create, share, extend, critique, and otherwise interact with these texts, they are brought into relation with each other. Some actors and their ideas become deeply influential; others remain at the margins of online discourse. Computer-assisted text analysis helps us make sense of such social structures that lie behind—or, perhaps more accurately, are constituted by—these texts. In this lab, we use a program called AntConc to develop an understanding of some basic concepts in corpus analysis and to move towards being able to understand, at a distance, the content of a large number of online texts. Sometimes the study of text in this way is called natural language processing (NLP), but this is a broad term that also refers to tasks relating to the comprehension of texts (transcribed and born-digital) by the computer and the automatic generation of text.

Text is stored relatively simply on disk, usually as a sequence of characters from a finite set. We can make a broad distinction between “plain” and “rich” text formats. Plain text formats generally stand as a minimal representation of text, excluding from consideration any formatting niceties such as font choice, text size, text color, character style (i.e. underlined, italic), document structure, hyperlinks, and so on. The default file extension for plain text is .txt. There are many rich text formats, of which .doc and .docx are perhaps the most familiar, due to the dominance of the software with which they are compatible: Microsoft Word. As an alternative, the OpenDocument Text format bears the extension .odt, and was published as the ISO/IEC DIS 26300:2006 standard. This file format is supported by Microsoft Office. It is also partly supported Google Docs, which stores documents in the cloud in a proprietary format such that every export method results in some format conversion, and, invariably, a loss of document information.

Q. In your opinon, is

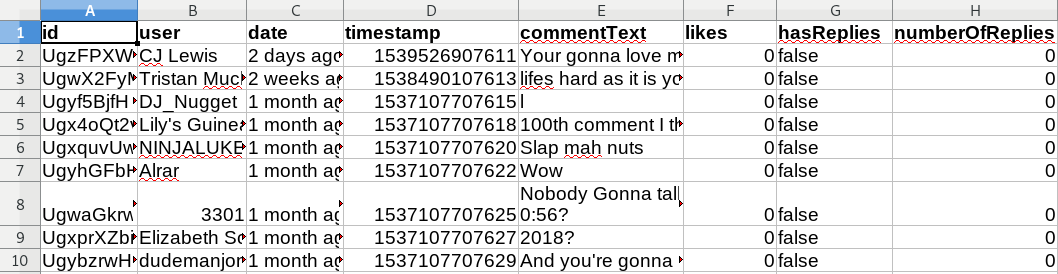

In this lab, we will work with plain text files. A collection of texts for analysis is called a “corpus” (lit. body in Latin). Becuase of the statistial redundancy in written language, text corpora can often be compressed very effectively without loss, so that when a corpus is distributed online as a .zip (compressed) file, it may consume disk space running to many multiples of the download file size. You can usually inspect the uncompressed size of such an archive using the operating system before you decide to unpack it.

Some applications can work directly on the compressed representation of the corpus, but in general, you’ll need to have enough free disk space to unpack the compressed corpus. In our case, the corpora we’ll work with are relatively small by most measures.

It should also go without saying that some of the concepts here are of general applicability to many other languages apart from English, with some adaptation where necessary.

To load a collection of texts into AntConc:

- First, unpack or ensure that the texts you are interested in are located in a folder.

- Click

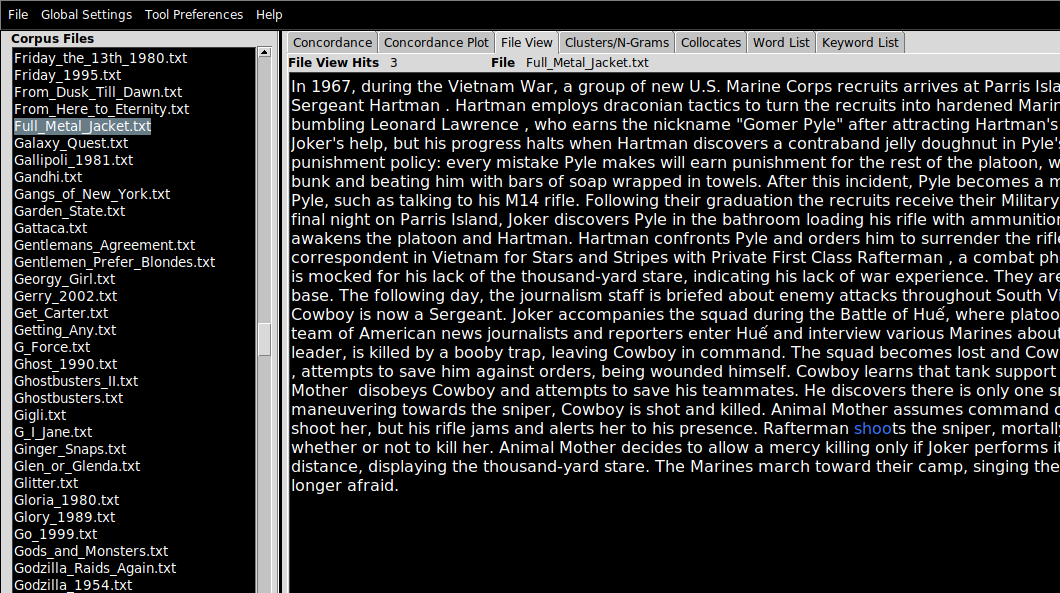

File > Open Dir...(or pressCtrl-D) and point AntConc to the directory containing your corpus. - Navigate to the

File Viewpane in which you can inspect the contents of the files you have just imported, by clicking on the filenames (which appear on the left-hand side). - If a search term is applied (see the search bar at the bottom of the screen), term matches will be highlighted in blue text (not especially visible on black).

In these examples, I am working with a corpus of 2,000 plot summaries of movies that were scraped from Wikipedia at some point in the past. If you want to follow along, data/movies.zip.

AntConc is a little old-fashioned looking but it does the job for pedagogical purposes. In the right-hand (larger) pane, there are a number of tab. Each of these correspond to a kind of analysis that is possible with the tool

- Concordance

- Concordance Plot

- File View

- Clusters/N-Grams

- Collocates

- Word List

- Keyword List

We have already looked at File View above. Note that I will mention the appropriate tab to use for each task in the header. For example…

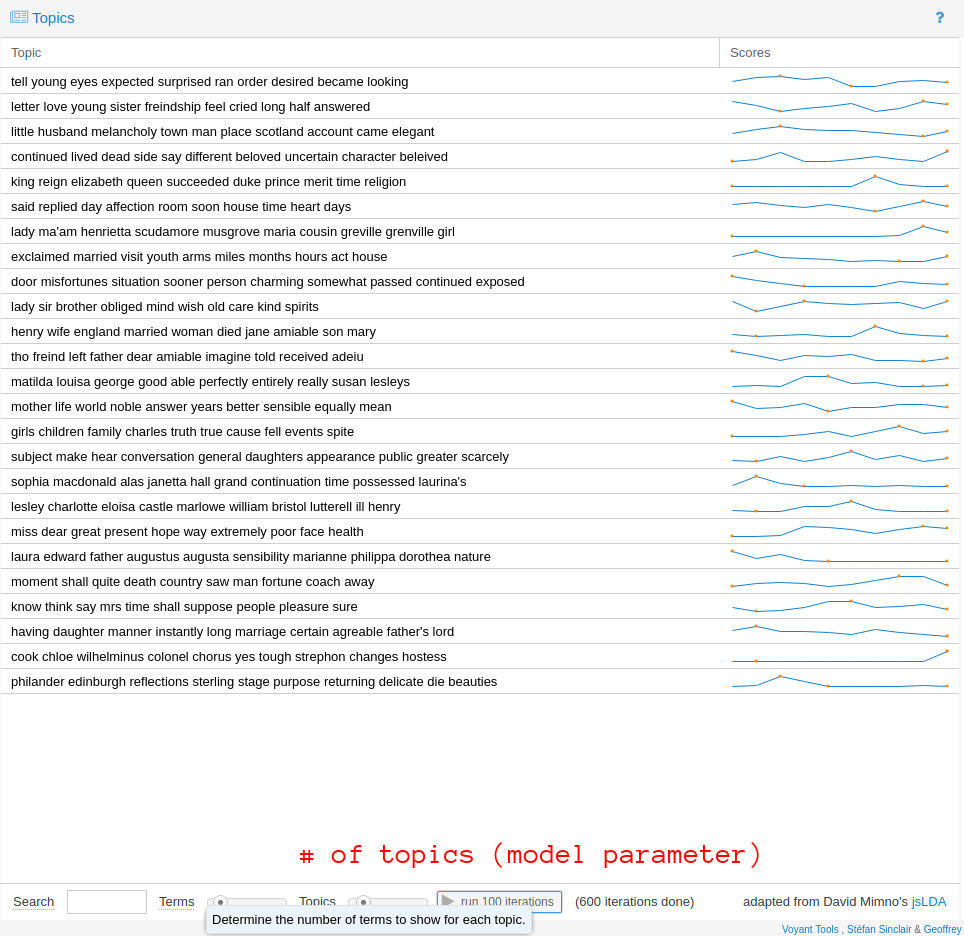

Given a large collection (a corpus) of documents, we want to find the most “important” words or terms that are used in that collection. Like the concept of influence or importance in a network, the notion of importance when it comes to words requires careful handling. In this lab, we’ll mostly be using raw term counts, but it’s important to know that these are not always that informative—and they are rarely, if ever, used to make sophisticated arguments about the meaning of large amounts of text.

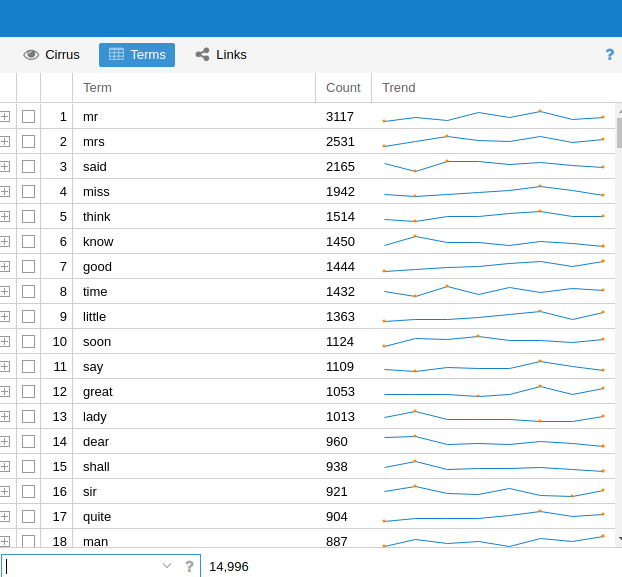

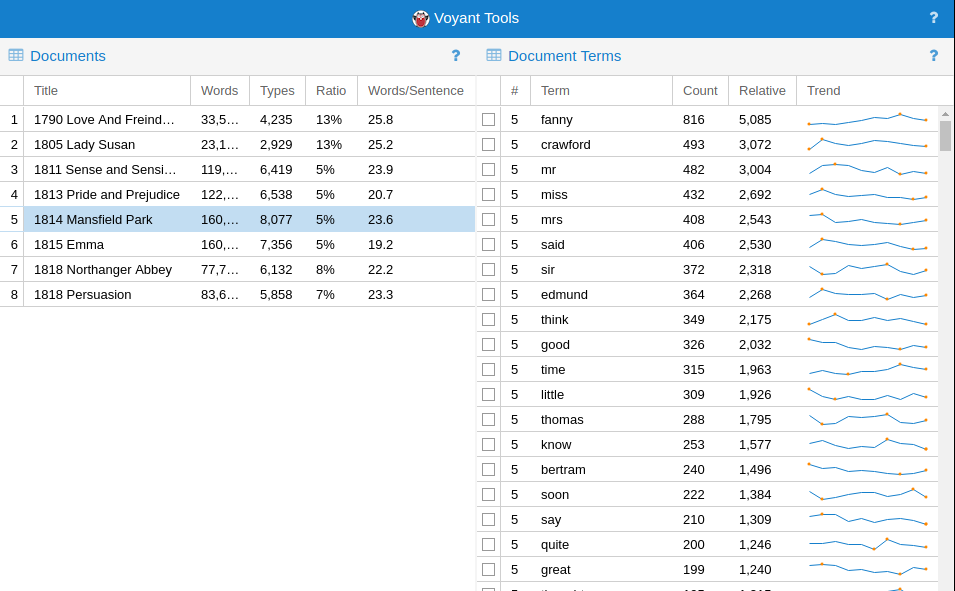

As a first pass at finding the most important topics in the corpus can just count words. On this view, the most “important” words are defined as the most common. To compute the raw counts for the corpus:

- Navigate to the Word List pane

- Click

Start

The results are accurate but not especially informative: most of the most common words in a representative corpus of English are not especially distinctive. This ranking draws from the Oxford English Corpus:

- the

- be

- to

- of

- and

Even though we know these texts are movie plot summaries, the top terms don’t really suggest much about the kinds of things you’d expect from a movie reivew. You get the picture: these are grammatically important words without which most utterances would make little sense, but they don’t give us much of an idea for what a text may be referring to. That doesn’t mean that statistics computed from these words are entirely uninformative. The patterns of usage of these common words have been shown to be useful in tasks like the forensic attribution of a text by anonymous or pseudonymous author to the true author, based on known-author comparanda.

One strategy, then, is to filter out these common words from the corpus entirely, so that less meaningful words do not clutter the results of our analyses. Lists of common (or uninformative) words are often called stopwords: like this one.

To add a list of stopwords for use in the Word List tool:

- Click

Tool Preferences - Click

Word Listin the left hand menu - Under

Word List Range, clickUse a stoplist below - Near

Add Words From File, click Open and point AntConc to your stopword file. - You can also add stopwords manually, using the

Add Wordfeature.

Q. Repeat the computation of the raw count data and notice the change. What kinds of words jump out at you? Why do you think these words are used so regularly in plot summaries of movies? Are there any unexpected words?

Every pane in AntConc has a search bar which can be used to narrow down the contents of any pane to a specific word or set of words. This search function supports the use of search operators, including common wildcards. Wildcards allow you to make fuzzy queries against the corpus. For example, inputting the term wom?n will match both women and woman (as well as any other analogous one-letter substitutions in the same part of the query term). The * operator can be used to open up the query further, as in sing*, which matches (amongst other words) sing, sings, singer, singing etc. but not casing, using, abusing etc.

The sort feature can sort alphabetically or by frequency count

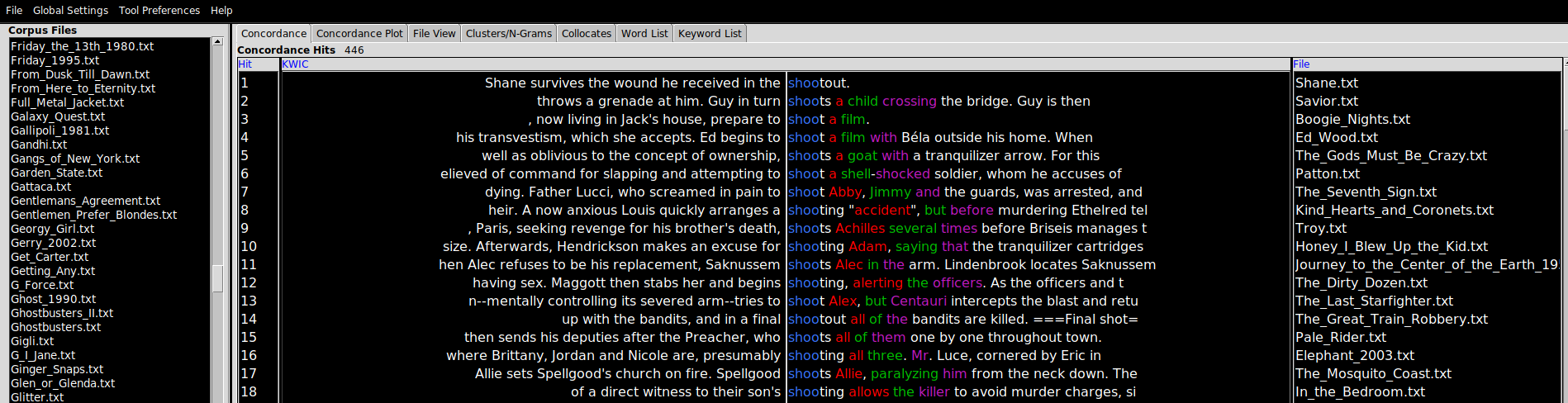

Language is a relatively complex phenomenon, and there are many ways in which the written word can be understood to correspond to its meaning. It is certainly not a one-to-one mapping, given the problems of polysemy, homographs, ambiguity, vagueness, etc. One way to recover concepts from text data is to take advantage of the regularities in some languages. The claim is that “shoots”, “shooting”, etc. are sufficiently similar to each other in meaning such that if we return the verb to the infinitive form, and process the text on that basis we don’t lose too much of these words’ senses. Lemmatization refers to the “smart” reduction of words to more gramatically straightforward forms; stemming usually refers to more naive methods of doing the same thing (removing endings like ‘-ing’ indiscriminately).

The goal of both stemming and lemmatization is to reduce inflectional forms and sometimes derivationally related forms of a word to a common base form.

We are also interested in recovering meaning from unreliable text: text with typos and spelling errors, especially common online.

Q. Why are these errors more common in online texts than in printed books?

Some forms of spelling regularization can help with this problem. Another way to deal with issues of this kind is to only work with character-level representations of text, which can be made resilient by design with respect to typos and variant spellings etc.

The computer scientist Karen Spärck Jones is credited with the introduction of a way to weight raw term frequency counts to improve their usefulness in information retrieval contexts, called TF-IDF (term frequency–inverse document frequency). TF-IDF operates when a corpus consists of a number of documents, and terms that occur frequently across a large number of documents (think about them as the “background” set of terms) are downweighted. Terms that are “unique” to documetnts (i.e. those that are less likely to appear across the corpus taken as a whole) are promoted on account of this. TF-IDF weighting is not implemented in AntConc, but it is possible to approximate its effects.

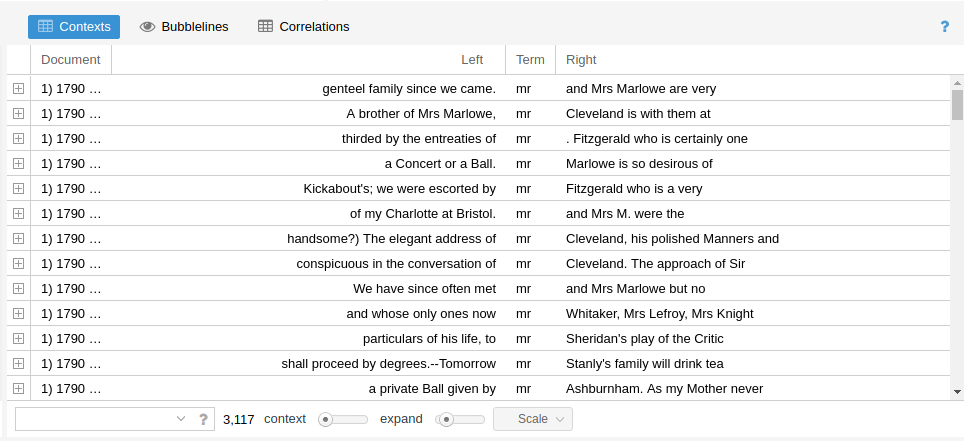

A concordance is an alphabetic list of the key words used in a text or corpus and a reference to their position. Some of the earliest concordances prepared were of religous texts (of the Bible, in English, printed around ~1470). One of the first electronic text processing projects was Fr. Roberto Busa’s Index Thomisticus, a 30 year project to index the complete words of Thomas Aquinas that began in 1949..

The condcordance view requires a query term before it will display the query term and all of the linguistic contexts in which it appears in a view known in shorthand as KWIC (standing for “Key Words In Context”), a layout which shows the query word in the position it appears in each of the sentences in the corpus in which it is found.

There are a couple of useful features to point out at this stage. The Search Window Size parameter determines the size of the context in characters. Clicking on Advanced allows users to construct multi-word queries. This can be used as an alternative to lemmatization or stemmatization (see above for definitions of these terms), by adding common verb conjugations or noun forms in a list (as in “shot”, “shoots”, “shooting”) if you are interested not so much in the context for an individual word form and more in the context for certain concepts. Finally, the Clone Results tool can be used to spawn copies of an analysis (in any window) to facilitated side-by-side comparisons between query terms (e.g. “his” vs. “hers”, “above” vs. “beneath”).

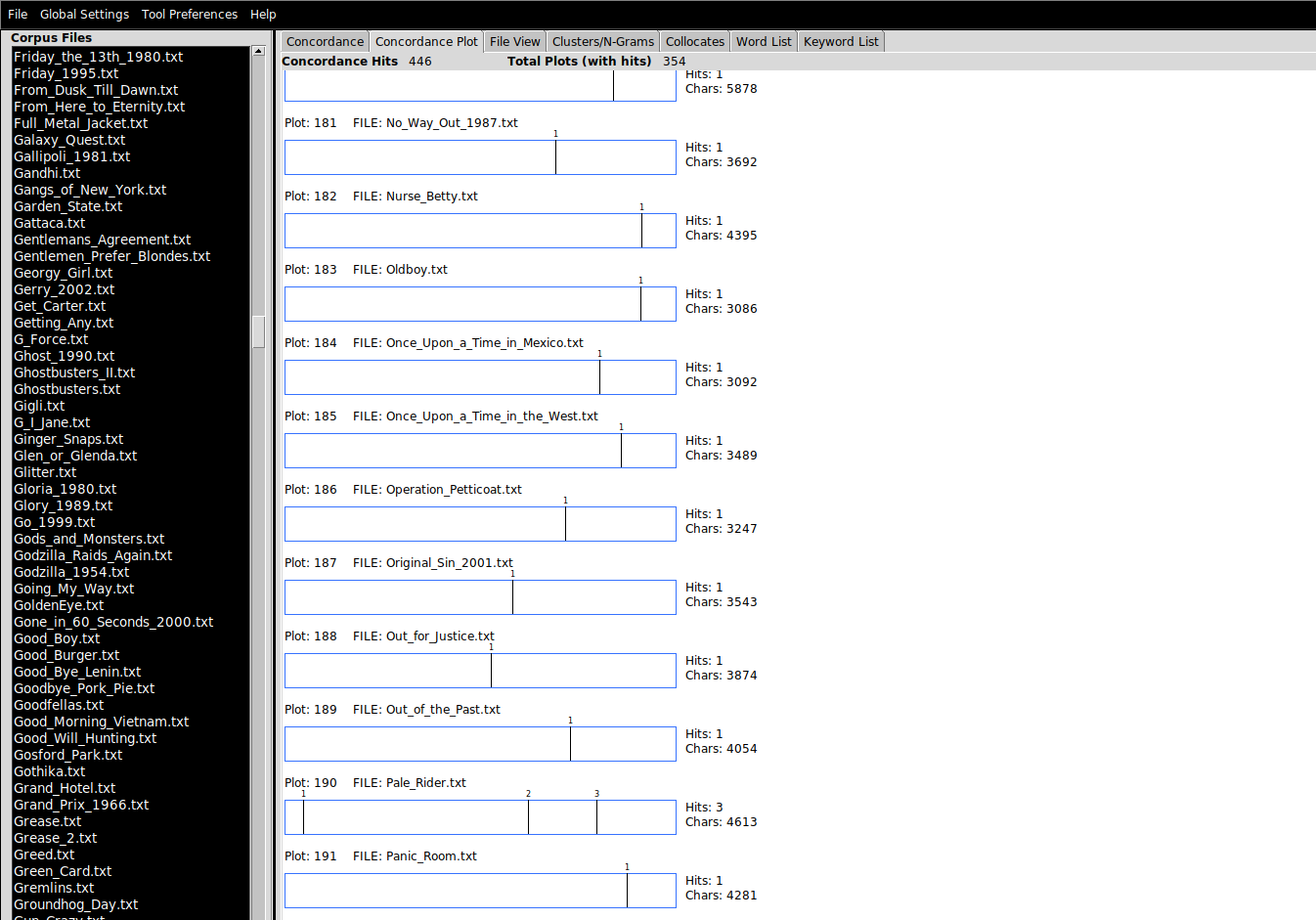

This is simply a way to plot the location of a search term as a visual representation of that term’s location(s) relative to the length of document in which it appears. Here, the search term was “shoots”. Scrolling through the list of plots and eyeballing them, it turns out that shooting tends to happen towards the latter half of movies, if not towards the final third (sometimes called the “third act”).

Q. What assumption is made in the foregoing paragraph about the relationship between the plot summary and the events of the movie?

There is an important setting in Tool Preferences for this tool, which determines whether the lengths of the barcodes are normalized: i.e. whether the relative lengths of the barcode plots should reflec the relative lengths of the underlying documents.

A bigram simply means two consecutive written language elements. In this case, it will refer to two words that appear consecutively in the corpus. A trigram, unsurprisingly, means three words; 4-grams, 5-grams, 6-grams, and so on. You will frequently encounter the term n-gram, whcih just means a consecutive pattern of any size (the n stands in for any integer).

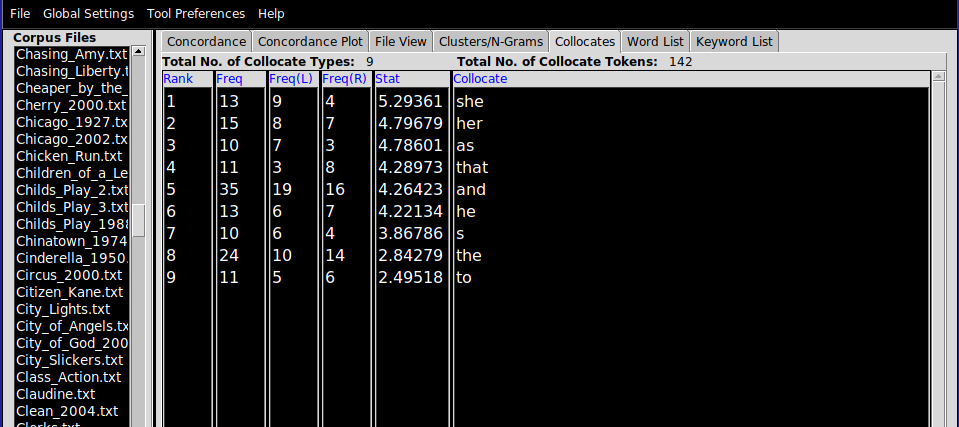

This pane allows users to see what the most common clusters of words are. Tweak the Cluster Size parameters to reveal larger clusters.