By

Dr Malcolm Morgan, Research Fellow in Transport and Spatial Analysis, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds

Dr Layik Hama, Leeds Institute for Data Analytics, University of Leeds

Vector Tiles are a great new way to serve geographic data via web maps. They provide significant improvements over traditional methods of creating web maps but are a little more complicated to set up.

This tutorial explains how to use Vector Tiles for both base maps but more importantly, how to create your own vector tile layers. It also explains how to do this using completely free software and avoiding licencing or subscription fees.

In this tutorial, we will cover going from a source geographic file format to viewing tiles on your website using Mapbox GL JS. To achieve this, we will only use free open source tools provided by Mapbox and others. The documentation, we feel requires some improvement for someone to accomplish this, hence this blog post.

Web maps (Haklay et al. 2008) are a great way to present your data; they allow for interactivity, and for users to zoom into their area of interest. But they have a problem with large datasets; they become slow and unresponsive. This decline in performance is because you must download all your data before it is put onto the map. The solution was to tile the data.

Tiling breaks your data into many small square datasets (tiles) than can then be downloaded individually. This means that you only have to download the tiles in the area you interested in rather than the whole dataset. This both reduces the amount of data that the webserver has to send to the user and reduces the amount of data the user's computer must hold in memory.

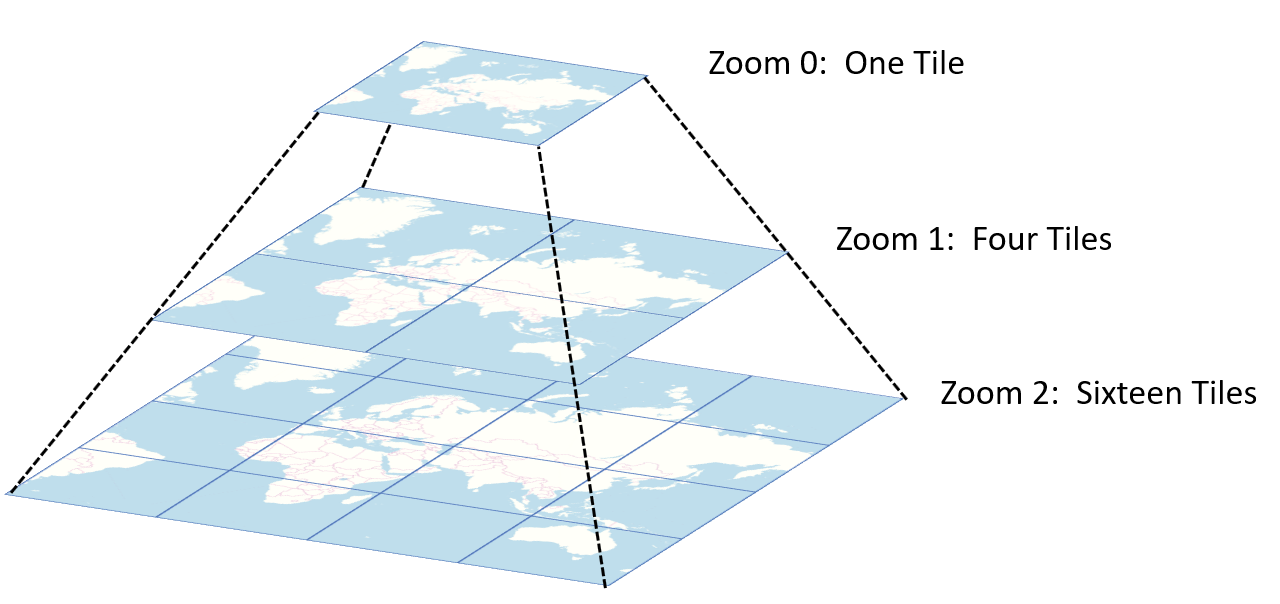

Tiling was first implemented for raster data with each tile being a 256 x 256 pixel PNG image. It works well for basemaps and is still used by many websites today such as OpenStreetMap. Tiles exist in a pyramid structure; at the top of the pyramid (zoom level 0), the whole world is a single tile. Each step down the pyramid (zoom levels 1,2,3, etc.) increases the number of tiles by a factor of 4. Tilesets typically go down to about zoom level 19, at which point one tile covers an area about the size of a single building.

Raster tiles have two significant limitations:

- They are static – you can't click on an image to get extra information or dynamically change the styling of the map.

- They are large – while each tile is small, hosting all the tiles uses up a lot of space on your server. For example, a tileset for the UK is around 15 GB.

Due to these limitations, raster tiles are mostly used for base maps and are served by third-party services.

Vector Tiles are a newer take on the idea of tiling. Instead of many images, the tiles are lots of tiny vector datasets. These vector tiles are usually smaller, as not all pixels need to be coded. They are also great for visualising data. For example, if you wanted to make an interative Choropleth map with the ability to switch between different variables. With raster data, each variable would require its own tileset to be created and downloaded. But vector tiles can contain both geometry and many variables in a single tile. Thus they can be dynamically rendered client-side using JavaScript, and you can even perfom calualtions on variables such as finidng the ratio of two variables.

Most of the tools in this tutorial are Linux command line applications. So you will need a Linux computer with permission to install the software. If you do not have a Linux computer, you can.

- Create a virtual machine using software such as Virtual Box

- On Windows 10, use the Windows Subsystem for Linux

- Some of the tools are supported on Mac; if you have a Mac check the documentation

This tutorial uses a range of different software; not all software is required for every workflow. The flowcharts below highlight which tools are needed to perform each task.

tippecanoe (essential)

Tippecanoe is free software from Mapbox which converts .geojson files into vector tiles. It is also supported on Mac.

mb-util (reccomended)

Tippecanoe is free software from Mapbox which converts .mbtiles files into a folder of .pbf vector tiles.

A text editor (essential)

We will be editing some files, and a simple text editor will be required.

A HTML Server (essential)

This tutorial was written with Apache in mind, but any modern HTML server will do.

An (S)FTP client (essential)

You will need to upload files to your server. Usually, this is done with an (S)FTP client such as Filezilla.

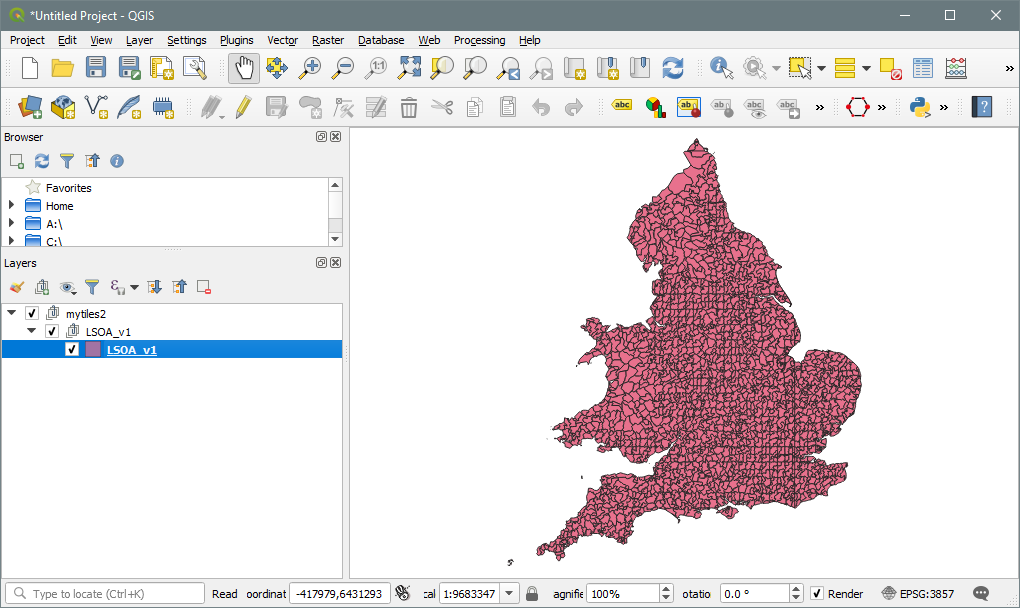

GIS Software (essential)

You will need to project your dataset to epsg:4326 and convert them into the .geojson format. This can be done in a wide range of free GIS software such as QGIS. QGIS is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux.

tilemaker (optional)

If you wish to generate your own basemap tiles.

OpenMapTiles (optional)

An alterative way to make your own basemap tiles. Alternatively, you can download pre-made tiles which may be free or may require a one-off payment. OpenMapTiles is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux (see below).

docker (optional)

OpenMapTiles requires docker. Docker is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux.

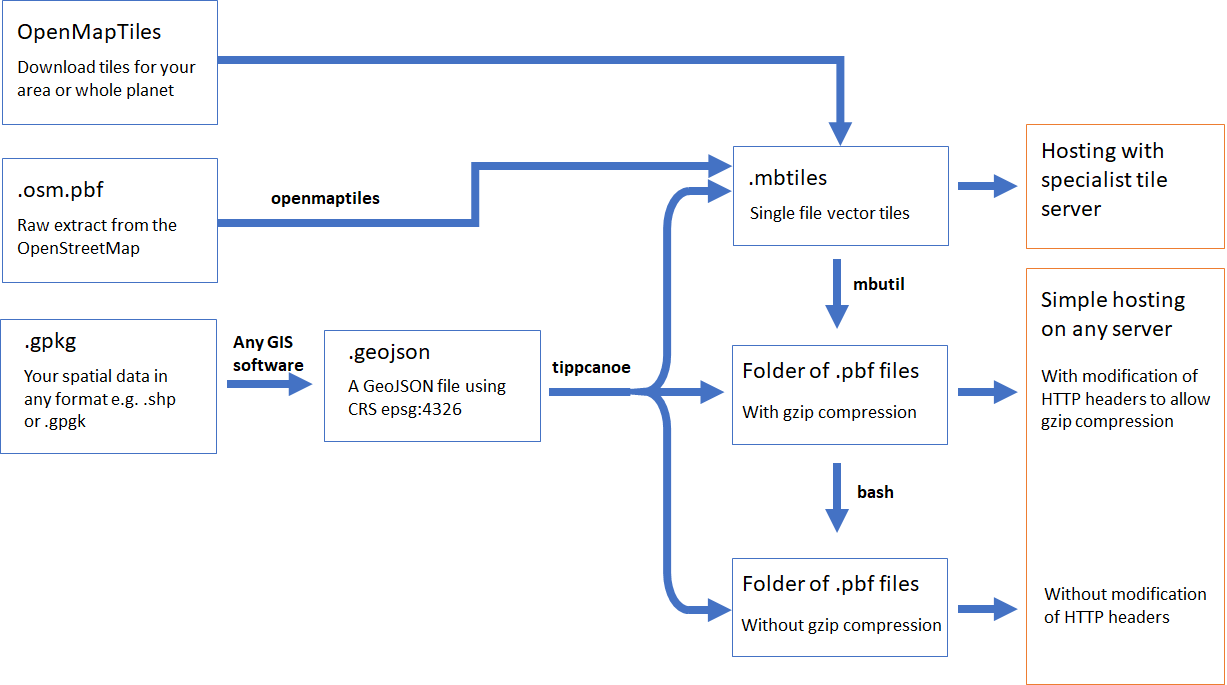

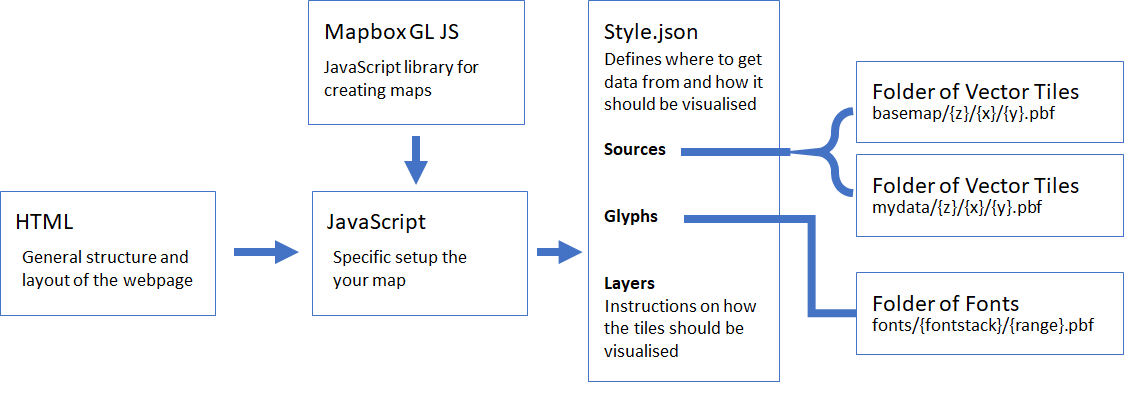

This diagram shows the various ways in which Vector Tiles can be created and then hosted:

Before generating the vector tiles, you must make a decision on whether they will be gzipped or not. gzip is a compression standard which is supported by all modern browsers. The compressed .pbf files are about 25% of the size of the uncompressed ones. This saves storage space on your server and speeds up the download of the tiles, giving your users a better experience.

So gzipped .pbf files are better. But to use the gzipped files, you must modify the HTTP Headers to include:

Content-Encoding: gzip

This will tell the user's browser that the files are gzipped and to un-gzip them before trying to use them. Without this HTTP Header, the browser will be unable to read and render the tiles. So gzipping is only a good idea if you are able to modify the HTTP Headers on your server.

The sections below will outline how to generate tiles with or without gzipping, and how to modify HTTP headers when using Apache server. If you are using different server software, check for a tutorial on how to modify HTTP headers.

To have a basemap, you have three main choices:

- Get your basemap from a 3rd party service such as Mapbox; depending on your usage you may need to pay.

- Get pre-made tiles from OpenMapTiles; this is free for non-profit uses but requires a $1,000 fee for commercial projects.

- Generate your own tiles; free but most difficult.

You can sign up for a free account at www.openmaptiles.com .

You can download tiles for the whole planet or just a country or region. OpenMapTiles allow for free download of tiles for education and evaluation purposes but charge up to $1,000 for a one-time download for commercial projects.

The download will be a single .mbtiles file.

To convert to a folder of gzipped tiles, we will use mb-util:

./mb-util --image_format=pbf countries.mbtiles countriesYou can convert the gzipped files to ungzipped files with the following bash commands:

gzip -d -r -S .pbf *

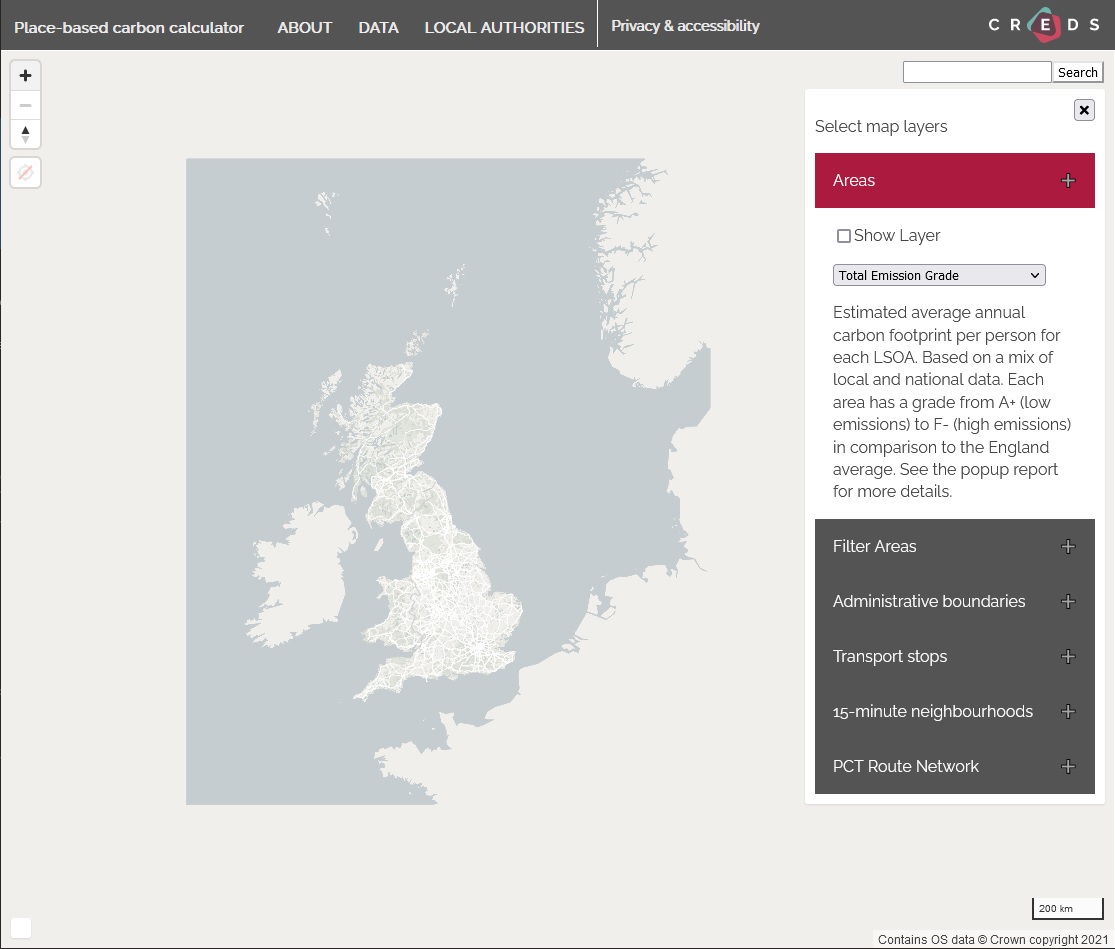

find . -type f -exec mv '{}' '{}'.pbf \;If your project is only in Great Britain you can used the Ordnance Survey Open Zoomstack which provides a MBTitles file or a GeoPackage of the data. We used the Zoomstack as the basemap in the Place-Based Carbon Calculator. In this case we built a custom tileset from the GeoPackage data as we found the performance of the tileset provided by the OS to be poor. This is because the Open Zoomstack contains a lot of data, and for our purposes a simpler map was preferable. So we extracted geojson files from each of the layers in the Geopackage file and made several modifications.

- Removed some layers that we did not need such as the contour lines and building outlines (this reduced file sizes significantly)

- Created high/medium/low version of some layers and filtered out some data for the lower zoom levels. For example removing minor roads from the low zoom levels

- Produced three different tilesets for high/medium/low zoom levels and then combined them into a single tileset.

- Created a custom sea layer. In the OS data the sea is assumed to be the background with a layer used to define the location of the land. For our use case, users would mostly be looking at the land, so we chose to invert this and create a tileset where the land was the background and the sea was specified. We also added a low resolution coastline for Europe so that Great Britain was mapped in context.

To save disk space the sea polygon is only close to the UK coastline on high zoom levels. We designed this to be hard to spot but if you zoom into the Isle of Mann close enough the Sea disappears and everything becomes the default land background.

An example of the Tippecanoe command to make the basemap tileset.

tippecanoe --output-to-directory=OSzoomStackSeamMed --attribution=OS --minimum-zoom=9 --maximum-zoom=11 --drop-smallest-as-needed --simplification=10 --force boundaries.geojson foreshore.geojson greenspace.geojson sea.geojson names.geojson national_parks.geojson rail.geojson railway_stations.geojson roads.geojson surfacewater.geojson urban_areas.geojson woodland.geojson

Notice how we can list multiple geojson files to combine them into a single tileset. Also notice that when making different tilesets for different ranges you need to put each into a separate folder. Otherwise tippecanoe will delete the old tileset when you create a new one.

To generate your own basemap you will need to install Docker and openmaptiles. There are installation instructions available. The OpenMapTiles can easily built for an individual country or region using the quick start guide.

OpenMapTiles uses Geofabrik regions, so you can build a tile layer for any one of those regions with minimal effort. OpenMapTitles also draws in some low-resolution data for the rest of the world, so your map does not appear to be floating in a sea of nothing.

The tools we use to create Vector Tiles require the input data to be in the .geojson format and to be using the epsg:4326 coordinate reference system.

Converting a shapefile into tile:

An example file in question would be the UK MSOA boundaries which are roughly ~600M in size when converted to plain .geojson file.

If you have GDAL installed then the following command will achieve this, once you have downloaded the shapefile.

ogr2ogr -f GeoJSON msoa.geojson /tmp/Counties_and_UA/Counties_and_Unitary_Authorities_December_2017_Full_Extent_Boundaries_in_UK_WGS84.shp -lco RFC7946=YESDownloading and converting the data can also be achieved in R. For instance:

# get LAs

folder = "/tmp/Counties_and_UA"

if(!dir.exists(folder)) {

dir.create(folder)

}

url = "https://opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/f341dcfd94284d58aba0a84daf2199e9_0.zip"

msoa_shape = list.files(folder, pattern = "shp")[1]

if(!file.exists(file.path(folder, msoa_shape))) {

download.file(url, destfile = file.path(folder, "data.zip"))

unzip(file.path(folder, "data.zip"), exdir = folder)

msoa_shape = list.files(folder, pattern = "shp")[1]

}

library(sf)

msoa = st_read(file.path(folder, msoa_shape))

st_write(msoa, "~/Downloads/msoa.geojson")We have not tested Python but there are packages that can read ESRI Shapefiles and interpret them into GeoJSON.

Let us convert this to a format called .mbtiles, which is essentially an SQLite file zipped and formatted the way Mapbox sofware such as Mapbox GL (hence the 'mb' prefix) can read it.

We will use tippecanoe repo/package to achieve this.

tippecanoe -zg -o out.mbtiles --drop-densest-as-needed msoa.geojsonConverting to a folder of .pbf tiles with gzip compression:

tippecanoe -zg --output-to-directory=mytiles --drop-densest-as-needed msoa.geojsonIf you don't want to use gzipped .pbf files then you can generate uncompressed files with tippecanoe by:

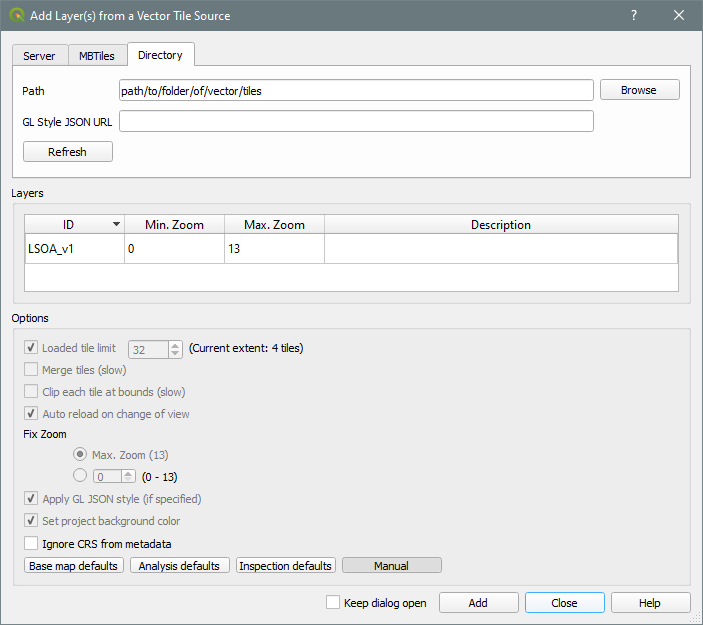

tippecanoe -zg --output-to-directory=mytiles --drop-densest-as-needed --no-tile-compression msoa.geojsonIf you have QGIS installed, the Vector Tiles Reader plugin is an easy way to view your finished tiles. Simply install the plugin from the plugin manager and then in the Vector menu choose Vector Tiles Reader > Add Vector Tiles Layer.

On the Directory tab use the Browse button to find the location of your folder of Vector Tiles, or if you have created a single MBTiles files use the MBTiles tab.

You do not need to specify a Style JSON URL to view the tiles.

//TODO use the mbtile viewer to view the tiles we generated.

We can now serve the .mbtiles in a Mapbox GL JS instance. The drawback here, is an initial lag in downloading the whole file by the client (browser); the pro is, as you can probably guess, that this happens only once. It was perhaps developed for mobile apps and works perfectly for such cases.

//TODO add html example with mbtiles //TODO test servers and CORS

However, not everyone can do this, as the size of the package could be large and slower connection clients would be punished harshly. It is important to shorten the "time to first byte". That is why we should consider unzipping the package into single pbf tiles. Protocol buffers (pbf) is a language-neutral serialization by Google.

We can do this as follows:

When hosting vector tiles on your own server, you have two main choices:

- Install a specialist tile hosting server such as TileServer and use a

.mbtiles - Generate individual

.pbftiles and then upload them to a folder on your server.

See documentation at https://openmaptiles.org/docs/ .

This method is very simple and does not require the installation of specialist software on your server. This means you can even host the tiles on file servers such as Amazon S3 or Google Cloud. It should also improve the hosting performance, as your server does not need to do any processing, simply serve the requested files. The downside is that you get no support or helpful features included in your chosen software. It is also less suited to hosting datasets that you expect to update regularly.

Note that the cost of hosting tiles on Google Cloud or Amazon S3 can be very low, e.g. $0.023 per GB per month, but you may also be charged for interactions with that storage such as file uploads. We have tested hosting titles on Google Cloud Storage which offers a 5 GB free tier, but found that uploading 5 GB of titles resulted a £12 charge in API requests. Conversely traditional webhosts will charge more per GB (e.g. $0.2 per GB per month) but will not charge for uploads. The cheapest option for you will depend on the frequnecy that you expect to update your tilesets.

Once you have created your tiles, simply upload them to your server using an (S)FTP client such as Filezilla. We suggest you create a tiles folder on your server and keep each tileset in its own subfolder.

There are two reasons you may want to modify HTML headers.

- To enable gzip compression (see above)

- To enable CORS

Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is required if you wish to host the tiles on a different server from the one that will serve your website. Common use cases are:

- You are using separate servers for tile hosting (e.g. Google Cloud or Amazon S3) than for web hosting.

- You wish to use the Maputnik style editor to build your

style.jsonfile (see below). If you are using Apache server, HTML headers can be simply modified by adding a.htaccessfile into the folder containing your vector tiles. The.htaccessfile will apply to all the subfolders below the file, so storing all your tiles in a single folder is a good idea.

Example folder structure

/index.html

/tiles

.htaccess

/basemap

/mytiles1

/mytiles2

Example .htaccess file

Header add Access-Control-Allow-Origin "*"

Header add Access-Control-Allow-Methods: "GET"

Header set Content-Encoding: gzip

If your .htaccess file is not working you may need to enable this feature in your server config file.

Note that setting Header add Access-Control-Allow-Origin to "*" means any website can view your tiles. You may wish to opt to specify which sites can access your tiles.

If your map includes text tables, such as road or country names, you will need to provide the fonts you wish to use. You can download a selection of fonts from this repo and upload them to your server in a folder called fonts. You will need to unzip the files and upload them in the file structure shown below.

Example folder structure

/index.html

/fonts

/metropolis

Metropolis-Black.pbf

Metropolis-BlackItalic.pbf

/noto-sans

NotoNaskhArabic-Bold.pbf

/mytiles2

There are many ways to view vector tiles, but when building a website, we recommend using Mapbox GL JS. Mapbox GL JS is a Javascript library which takes advantage of WebGL. This means the library can use both the GPU and the CPU to render your maps, rather than just the CPU as was the case with older libraries such as Leaflet. The use of the GPU means that you can render larger and more complex datasets such as 3D maps, animations, and other advanced features.

Although Mapbox GL JS is open source, it is maintained by Mapbox and most of the documentation steers you towards using Mapbox's paid services. However, it works equally well with vector tiles hosted from any location. Note that Mapbox GL JS v2 and onwards is only quasi- open source, as it must be used according to the Mapbox Terms of Service which includes having an account that monitors (and potentially charges) for map loads even when you are using your own data.

There is an open source fork of Mapbox V1 called Maplibre but it is experimental.

Mapbox GL JS has good documentation and lots of examples. This tutorial will focus on the changes required for hosting your own vector tiles and supporting multiple vector tile layers.

This example is based on the Mapbox Getting started example.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Display a map</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1,maximum-scale=1,user-scalable=no" />

<script src="https://api.mapbox.com/mapbox-gl-js/v1.9.0/mapbox-gl.js"></script>

<link href="https://api.mapbox.com/mapbox-gl-js/v1.9.0/mapbox-gl.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<style>

body { margin: 0; padding: 0; }

#map { position: absolute; top: 0; bottom: 0; width: 100%; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div id="map"></div>

<script>

mapboxgl.accessToken = 'your-access-token-here';

var map = new mapboxgl.Map({

container: 'map', // container id

style: 'https://www.mysite.com/tiles/style.json', // stylesheet location

center: [-1, 53], // starting position [lng, lat]

zoom: 9 // starting zoom

});

</script>

</body>

</html>The key changes from the Mapbox example are; that mapboxgl.accessToken must be defined (though if you are using Mapbox GL v1, is not used, as we are not connecting to the Mapbox services, and so you can put any string), and the location of the style.json has been changed to a URL on your server.

You will notice that in the HTML example above, we made no reference to where our vector tiles are of how they should be displayed. This is because all this information is contained within a stylesheet .json file. The full stylesheet specification is available, but a simplified structure is shown below.

{

"version": 8,

"name": "Basic",

"metadata": {

"openmaptiles:version": "3.x"

},

"sources": {

"openmaptiles": {

"type": "vector",

"tiles": ["https://www.mysite.com/tiles/basemap/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"]

},

"msoa": {

"type": "vector",

"tiles": ["https://www.mysite.com/tiles/msoa/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"

]

}

},

"glyphs": "https://www.mysite.com/fonts/{fontstack}/{range}.pbf",

"layers": [

{

"id": "background",

"type": "background",

"paint": {

"background-color": "hsl(47, 26%, 88%)"

}

},

{

"id": "landuse-residential",

"type": "fill",

"source": "openmaptiles",

"source-layer": "landuse",

"filter": [

"all",

[

"==",

"$type",

"Polygon"

],

[

"in",

"class",

"residential",

"suburb",

"neighbourhood"

]

],

"layout": {

"visibility": "visible"

},

"paint": {

"fill-color": "hsl(47, 13%, 86%)",

"fill-opacity": 0.7

}

},

{

"id": "msoa_layer",

"type": "fill",

"source": "msoa",

"source-layer": "msoa",

"layout": {

"visibility": "visible"

},

"paint": {

"fill-color": "hsl(105, 13%, 86%)",

"fill-opacity": 0.7

}

}

],

"id": "basic"

}

The style.json file is good for vector tiles that you always want to show such as basemaps, but is not dynamic. If you have layers that you wish to toggle on and off then you need a more dynamic method to style the vector tiles.

Another Mapbox example is useful:

map.on('load', function() {

map.addSource('msoa', { // define the location of a new vector tileset

'type': 'vector',

'tiles': ["https://www.mysite.com/tiles/msoa/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"],

'minzoom': 6,

'maxzoom': 14

});

map.addLayer( // add a layer to the map

{

'id': 'msoa',

'type': 'fill',

'source': 'msoa', // must match name in .addSource

'source-layer': 'msoa', // must match layer name given when titles were created check metadata.json

"paint": { // define how to colour the polygons

"fill-color": {

"property": "population",

"stops": [

[1000, "#053061"],

[2000, "#053061"],

[3000, "#2166ac"],

],

"type": "exponential"

},

"fill-opacity": 0.7

}

}

});As vector tiles are so efficent in comparion to raster tiles, it is tempting to tread them like any other GIS file format. In a geojson or a geopackage is it common to have many attribute columns for each geometry. It is certainly possible to do this with vector tiles, but it must be done with care.

The main issue is that by default each tile is capped at 500 kB in size (though this can be adjusted). This ensures fast downloading and rendering. Tippecanoe will remove small feaures from a tile to keep to the file size limit. This works really well for base maps, as you don't want to see every building when viewing a map of a whole country. And once you have zoomed in enough to see buildings, there are only a few that need to be downloaded and rendered.

But this approach does not work so well for data, especially area-based data. In this case small areas disappearing or being coaled with larger areas can spoil a good piece of data visualisation. So to keep as many of your features visible as possible, you need to think of other ways to reduce the tile size.

Tippecanoe has a built in simplification options including:

- --simplification=10 this can be set to a numerical value. You can go upto about 10 without noticing the loss in quality.

- --drop-densest-as-needed removed small objects in a crowded tile, works well for point data

- --coalesce-densest-as-needed merge small object in a crowded tile, works well for polygon data especially if you need continouse coverage coverage

It is worth understanding how vector tiles store attribute data, as it is quite different to other GIS file formats. A full description is available, but the key point is that each vector tile contains a lookup table of all the possible values an attribute can have, and each feature stores the keys to that lookup table.

For example if you had a column of data in your geojson with the values "house", "park", "house", "lake" and another column "10.5", "1234", "12.4","567". The vector tile would create a lookup table house = 0, park = 1, lake = 2, 10.5 = 3, 1234 = 4, 12.4 = 5,567 = 6 and then the geometries] would simply store the keys 0,1,2,1 and 3,4,5,6. This system is excellent for storing text-based tags, when you have a small number of possible values which are used again and again (e.g. in a basemap). But this system is terrible for numeric data or any type of data where each value is used only once.

So you need to minimise the number attributes you have and the variability in your attributes. Things you can try:

-

Calculate an attribute on the fly: Instead of storing population, area, and population density in the vector tile, just store population and area and calculate the population density when required. See example.

-

Round numeric data to increase the chance of numbers being reused: Decimal numbers are likely to be unique (e.g. 23.4564), but integers are more frequently reused. Do you really need the full number, or would a rounded one do just as well?

-

Store numbers like scientific notation: Suppose you have two columns of values one that ranges from 1 - 100 and another that ranges from 1,000 to 100,000. There is little chance of repeated values. But if you scale them by powers of ten and round to an appropriate number of significant figures (e.g both 123,456 or 12.345 become 1234) you increase the chance of the same value being reused across different columns. In the javascript you can simply multiply each column back to its original size.

-

Replace numeric data with categorical data. If you are making a choropleth map then you only need to know which colour to use, not the exact value. This won't work if you also want to be able to click on an area to get the exact value.

For all these methods you can easily test their effectiveness on your data by checking for the total number of unique values in your data. The lower the better.

Haklay, Muki, Alex Singleton, and Chris Parker. "Web mapping 2.0: The neogeography of the GeoWeb." Geography Compass 2.6 (2008): 2011-2039.