Data Version Control or DVC is a command line tool and VS Code Extension to help you develop reproducible machine learning projects:

- Version your data and models. Store them in your cloud storage but keep their version info in your Git repo.

- Iterate fast with lightweight pipelines. When you make changes, only run the steps impacted by those changes.

- Track experiments in your local Git repo (no servers needed).

- Compare any data, code, parameters, model, or performance plots.

- Share experiments and automatically reproduce anyone's experiment.

The closest analogies to describe the main DVC features are these:

- Git for data: Store and share data artifacts (like Git-LFS but without a server) and models, connecting them with a Git repository. Data management meets GitOps!

- Makefiles for ML: Describes how data or model artifacts are built from other data and code in a standard format. Now you can version your data pipelines with Git.

- Local experiment tracking: Turn your machine into an ML experiment management platform, and collaborate with others using existing Git hosting (Github, Gitlab, etc.).

Git is employed as usual to store and version code (including DVC meta-files as placeholders for data). DVC stores data and model files seamlessly in a cache outside of Git, while preserving almost the same user experience as if they were in the repo. To share and back up the data cache, DVC supports multiple remote storage platforms - any cloud (S3, Azure, Google Cloud, etc.) or on-premise network storage (via SSH, for example).

DVC pipelines (computational graphs) connect code and data together. They specify all steps required to produce a model: input dependencies including code, data, commands to run; and output information to be saved.

Last but not least, DVC Experiment Versioning lets you prepare and run a large number of experiments. Their results can be filtered and compared based on hyperparameters and metrics, and visualized with multiple plots.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

dvc init |

Initializes a new DVC repository in the current directory. |

dvc add <file> |

Adds a data file or directory to DVC and starts tracking it. |

dvc remove <file> |

Stops tracking a data file or directory and removes its DVC metadata. |

dvc status |

Shows the status of DVC-tracked files and their corresponding stages. |

dvc push |

Uploads tracked files to the remote storage. |

dvc pull |

Downloads tracked files from the remote storage. |

dvc fetch |

Fetches tracked files from the remote storage without checking them out. |

dvc checkout |

Updates the workspace to match the specified DVC version (branch, tag, or commit). |

dvc run -n <stage> |

Runs a command as a new pipeline stage, specifying dependencies and outputs. |

dvc pipeline show |

Displays a visual representation of the pipeline. |

dvc lock |

Locks the DVC file, preventing it from being automatically updated. |

dvc unlock |

Unlocks the DVC file, allowing it to be automatically updated. |

dvc diff |

Shows changes between DVC-tracked files in different commits, branches, or tags. |

dvc remote add |

Adds a remote storage location to the DVC repository. |

dvc remote modify |

Modifies the configuration of an existing remote storage location. |

dvc config |

Configures DVC settings, such as core, remote, and cache settings. |

dvc commit |

Saves changes to the DVC-tracked files in the current working directory. |

dvc unprotect |

Makes DVC-tracked files writable in the working directory. |

dvc get |

Downloads a file or directory from a DVC repository into the current working directory. |

dvc import |

Imports a file or directory from another DVC repository into the current repository, tracking it as an external dependency. |

dvc export |

Exports a file or directory from the current repository to another location. |

dvc update |

Updates imported files or directories from their sources. |

Git is a popular version control system. It was created by Linus Torvalds in 2005, and has been maintained by Junio Hamano since then.

It is used for:

- Tracking code changes

- Tracking who made changes

- Coding collaboration

- Manage projects with Repositories

- Clone a project to work on a local copy

- Control and track changes with Staging and Committing

- Branch and Merge to allow for work on different parts and versions of a project

- Pull the latest version of the project to a local copy

- Push local updates to the main project

- Initialize Git on a folder, making it a Repository

- Git now creates a hidden folder to keep track of changes in that folder

- When a file is changed, added or deleted, it is considered modified

- You select the modified files you want to Stage

- The Staged files are Committed, which prompts Git to store a permanent snapshot of the files

- Git allows you to see the full history of every commit.

- You can revert back to any previous commit.

- Git does not store a separate copy of every file in every commit, but keeps track of changes made in each commit!

- Over 70% of developers use Git!

- Developers can work together from anywhere in the world.

- Developers can see the full history of the project.

- Developers can revert to earlier versions of a project.

- Git is not the same as GitHub.

- GitHub makes tools that use Git.

- GitHub is the largest host of source code in the world, and has been owned by Microsoft since 2018.

GitHub Actions is a continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) platform that allows you to automate your build, test, and deployment pipeline. You can create workflows that build and test every pull request to your repository, or deploy merged pull requests to production.

GitHub Actions goes beyond just DevOps and lets you run workflows when other events happen in your repository. For example, you can run a workflow to automatically add the appropriate labels whenever someone creates a new issue in your repository.

GitHub provides Linux, Windows, and macOS virtual machines to run your workflows, or you can host your own self-hosted runners in your own data center or cloud infrastructure.

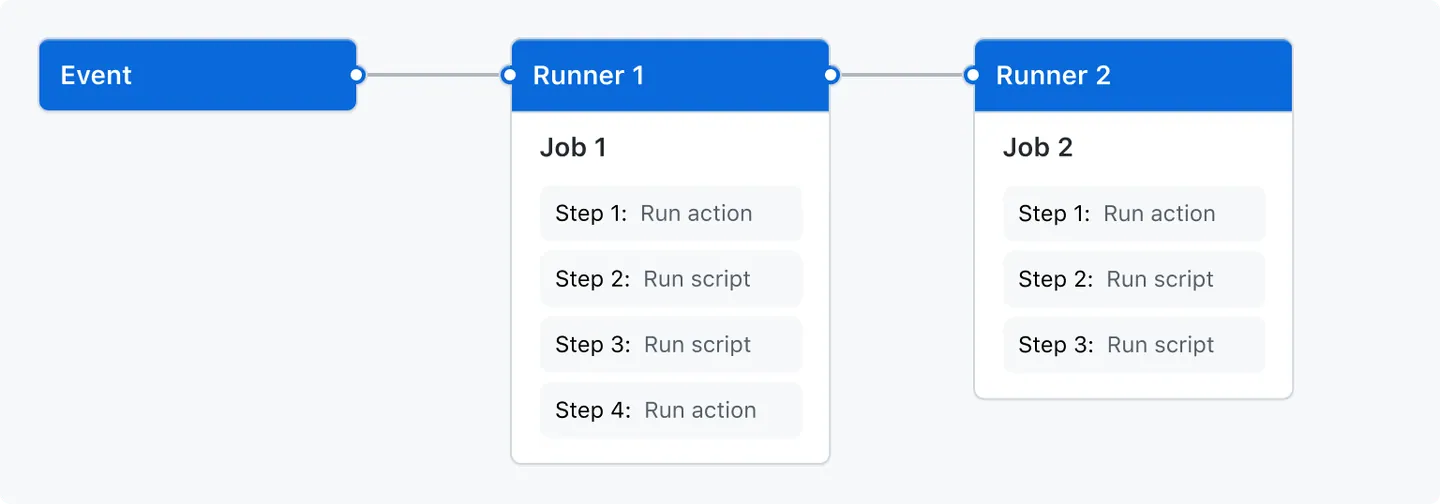

You can configure a GitHub Actions workflow to be triggered when an event occurs in your repository, such as a pull request being opened or an issue being created. Your workflow contains one or more jobs which can run in sequential order or in parallel. Each job will run inside its own virtual machine runner, or inside a container, and has one or more steps that either run a script that you define or run an action, which is a reusable extension that can simplify your workflow.

A workflow is a configurable automated process that will run one or more jobs. Workflows are defined by a YAML file checked in to your repository and will run when triggered by an event in your repository, or they can be triggered manually, or at a defined schedule.

Workflows are defined in the .github/workflows directory in a repository, and a repository can have multiple workflows, each of which can perform a different set of tasks. For example, you can have one workflow to build and test pull requests, another workflow to deploy your application every time a release is created, and still another workflow that adds a label every time someone opens a new issue.

You can reference a workflow within another workflow. For more information, see "Reusing workflows."

For more information about workflows, see "Using workflows."

An event is a specific activity in a repository that triggers a workflow run. For example, an activity can originate from GitHub when someone creates a pull request, opens an issue, or pushes a commit to a repository. You can also trigger a workflow to run on a schedule, by posting to a REST API, or manually.

For a complete list of events that can be used to trigger workflows, see Events that trigger workflows.

A job is a set of steps in a workflow that is executed on the same runner. Each step is either a shell script that will be executed, or an action that will be run. Steps are executed in order and are dependent on each other. Since each step is executed on the same runner, you can share data from one step to another. For example, you can have a step that builds your application followed by a step that tests the application that was built.

You can configure a job's dependencies with other jobs; by default, jobs have no dependencies and run in parallel with each other. When a job takes a dependency on another job, it will wait for the dependent job to complete before it can run. For example, you may have multiple build jobs for different architectures that have no dependencies, and a packaging job that is dependent on those jobs. The build jobs will run in parallel, and when they have all completed successfully, the packaging job will run.

For more information about jobs, see "Using jobs."

An action is a custom application for the GitHub Actions platform that performs a complex but frequently repeated task. Use an action to help reduce the amount of repetitive code that you write in your workflow files. An action can pull your git repository from GitHub, set up the correct toolchain for your build environment, or set up the authentication to your cloud provider.

You can write your own actions, or you can find actions to use in your workflows in the GitHub Marketplace.

For more information, see "Creating actions."

A runner is a server that runs your workflows when they're triggered. Each runner can run a single job at a time. GitHub provides Ubuntu Linux, Microsoft Windows, and macOS runners to run your workflows; each workflow run executes in a fresh, newly-provisioned virtual machine. GitHub also offers larger runners, which are available in larger configurations. For more information, see "About larger runners." If you need a different operating system or require a specific hardware configuration, you can host your own runners. For more information about self-hosted runners, see "Hosting your own runners."

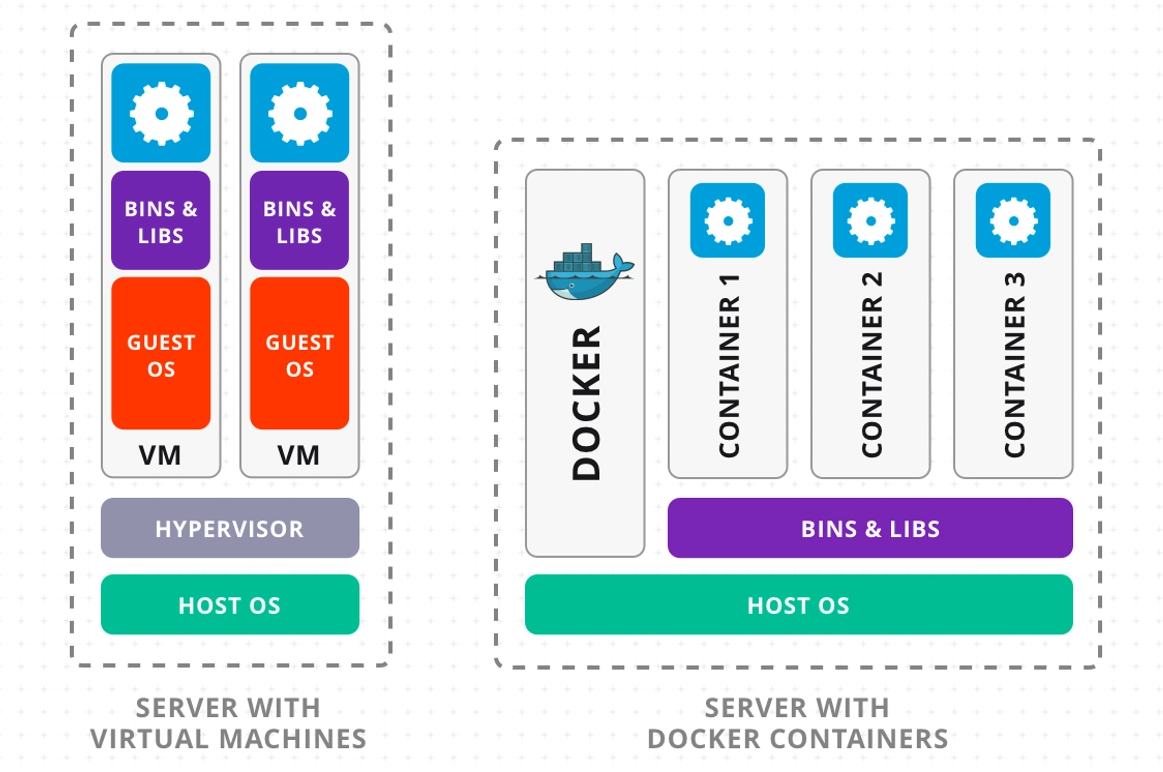

Docker is an open platform for developing, shipping, and running applications. Docker enables you to separate your applications from your infrastructure so you can deliver software quickly.

When delivering software in packages known as containers, Docker’s platform as a service offerings leverage OS-level virtualization. Containers are separate from one another, contain their own software, libraries, and configuration files, and only communicate with one another over pre-established channels. Virtual machines are heavier than containers since they all run under the same operating-system kernel.

An on-demand unit that may be developed to deploy a specific application or environment is called a “Docker Container.” To fully satisfy the criteria from an operating system perspective, it might be an Ubuntu container, CentOs container, etc.

In other words, I want to find a way to guarantee that, once my application is built, anyone can use it, regardless of the OS they are using, the version of the dependency they have, or even if they have it or not.

Containers were created specifically to accomplish this.

A container completely isolates the application it runs from any external environments or OS dependencies of any type.

One way to think about a container is as a wrapper for our application.

It includes the OS and all other dependencies for the program.

Okay, we get it. The “cloud” is the technology of the future, and in order to access all of its glitzy tools, we must employ containers. We need to install Docker because we’re going to containerize our program and deploy it using container orchestration tools.

One of the technologies, Docker, made use of the concept of isolated resources to develop a set of tools that enable applications to be packed with all necessary dependencies installed and run anywhere. The containers are described as follows by Docker:

In order for an application to execute fast and consistently from one computer environment to another, code and all of its dependencies are packaged together into a container, which is a common unit of software.

| Docker Command | Description |

|---|---|

docker –version |

Displays the version of Docker installed on your system. |

docker pull |

Downloads an image from a Docker registry (e.g., Docker Hub) to your local machine. |

docker run |

Creates and starts a new container from a specified image. |

docker ps |

Lists all running containers. |

docker ps -a |

Lists all containers, including those that are stopped. |

docker exec |

Runs a command in a running container. |

docker stop |

Stops a running container gracefully. |

docker kill |

Stops a running container immediately by killing its process. |

docker commit |

Creates a new image from a container’s changes. |

docker login |

Logs in to a Docker registry (e.g., Docker Hub) using your credentials. |

docker push |

Uploads a local image to a Docker registry (e.g., Docker Hub). |

docker images |

Lists all images stored locally on your machine. |

docker rm |

Removes one or more stopped containers. |

docker rmi |

Removes one or more images from your local machine. |

docker build |

Builds an image from a Dockerfile. |

Using a unique syntax, a text configuration file known as a Dockerfile is created. It provides step-by-step instructions for all the tasks you must execute in order to put together a Docker Image. This file is processed by the docker build command, creating a Docker Image that may be started using the docker run command or pushed to an ongoing image repository.

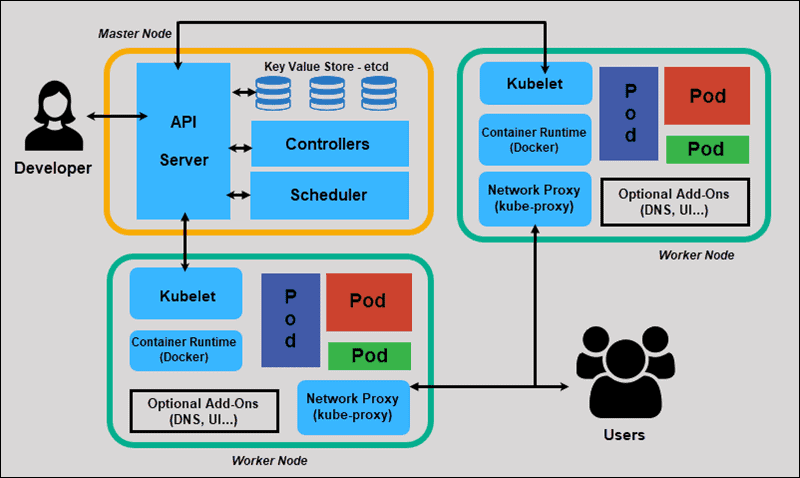

Kubernetes is an open-source platform designed to automate deploying, scaling, and operating application containers. It simplifies the developer’s task of managing containerized applications. It solves many problems teams face during managment of containerized applications. Some of these challenges are as below:

Managing containerized applications, whether using Docker containers or some other containers runtime, comes with its own set of challenges, such as:

- Scalability: As the number of containers grows, it becomes challenging to scale them effectively.

- Complexity: Managing numerous containers, each with its own role in a larger application, adds complexity.

- Management: Keeping track of and maintaining these containers, ensuring they are updated and running smoothly, requires significant effort.

Now that we have gone through the challenges of using containerized applications, let’s see how Kubernetes handle these challenges.

- Kubernetes steps in as a powerful platform to manage these complexities. It’s an open-source system designed for automating deployment, scaling, and operation of application containers across clusters of hosts.

- It simplifies container management, allowing applications to run efficiently and consistently.

- Kubernetes orchestrates a container’s lifecycle; it decides how and where the containers run, and manages their lifecycle based on the organization’s policies.

Some important benefits of Kubernetes are listed below:

- Efficiency: Kubernetes optimizes the use of hardware resources, saving costs.

- Reliability: It ensures that the application services are available to users without downtime.

- Flexibility and portability: Kubernetes supports diverse workloads, including stateless, stateful, and data-processing workloads. Its flexibility allows it to run on various platforms, from physical machines to cloud infrastructure.

- Security and resource management: It provides robust security features and efficient management of resources, ensuring that the infrastructure is secure and the resources are used optimally.

- Support for Docker and other container technologies: Kubernetes works well with Docker and other container technologies, offering a wide range of options for containerization.

- Open source community: Being open source, Kubernetes benefits from a large community of developers and users who contribute to its continuous improvement.

Below are some core components of Kubernetes.

- Pods: The smallest deployable units created and managed by Kubernetes. A Pod represents a single instance of a running process in your cluster and can contain one or more containers.

- Nodes: These are worker machines in Kubernetes, which can be either a physical or virtual machine, depending on the cluster. Each node runs Pods and is managed by the master.

- Deployments: They describe the desired state of your application, like which images to use and the number of Pod replicas. Deployments update your application to the desired state at a controlled rate.

- Services: They are an abstract way to expose an application running on a set of Pods as a network service. This decouples workloads from specific Pods, providing a consistent way to access the application.

- Ingress: This manages external access to the services in a cluster, typically HTTP. Ingress can provide load balancing, SSL termination, and name-based virtual hosting.

- Namespaces: Namespaces help split a Kubernetes cluster into sub-clusters, making it possible to divide resources between different projects or teams.

- Labels and Selectors: They are powerful tools that allow you to organize and select subsets of objects, like Pods, based on key-value pairs for more precise resource management.

- Control plane components: The control plane’s components, including the kube-apiserver, etcd, kube-scheduler, and kube-controller-manager, work together to manage the cluster’s state. Ensuring high availability of the control plane is crucial for production environments.

- Self-healing mechanisms: Kubernetes constantly checks the health of nodes and containers, restarting those that fail, replacing them, and killing those that don’t respond to user-defined health checks.

Below are some example cases where developers can take advantage of Kubernetes to scale and manage their applications.

- In a typical cloud-based application, Pods run the application’s containers, often with Docker. These Pods are managed by Deployments to ensure the application runs efficiently.

- Nodes provide the necessary infrastructure and services to ensure that the application is accessible.

- Ingress controllers manage external traffic and direct it to the correct Services.

- Namespaces help in managing environments like development, testing, and production within the same cluster.

It’s common to see Docker and Kubernetes mentioned together, leading to some confusion. While they are related, they serve different purposes in the world of containerized applications. Let’s see how.

- Docker is pivotal for developers looking to containerize their applications, making it the go-to platform for creating containers.

- It simplifies the process of packaging an application, along with its environment, into a single container.

- This container can then be easily transported and run across different environments, ensuring consistency and reducing “it works on my machine” problems.

- Kubernetes doesn’t replace Docker but complements it by handling the orchestration of containers created by Docker.

- It addresses the challenge of running and connecting containers across multiple hosts, managing the complexities of high availability, and service discovery.

- Kubernetes is designed to respond to the dynamic nature of modern cloud environments, scaling up or down as needed and rolling out updates without downtime.

- Docker and Kubernetes together form a powerful synergy for deploying applications.

- While Docker encapsulates the application’s environment, Kubernetes intelligently manages the containers across a fleet of machines.

- Docker and Kubernetes are not competitors; they are complementary technologies that work together to streamline the development and deployment of applications.

- Kubernetes can orchestrate not only Docker containers but also containers from other runtimes, showcasing its versatility.

Kubernetes is often mentioned in DevOps discussions, which leads to the misconception that it’s a DevOps tool, although it is not. In reality, Kubernetes is more specialized than the broad suite of tools typically associated with DevOps.

- Designed for systems engineers: Initially engineered for large-scale, containerized environments.

- Strengths: Excels in container lifecycle management, scaling, and high availability.

- Becoming a standard: Despite being system-centric, Kubernetes is essential in modern container management.

- Mandatory understanding: Cloud-centric software delivery makes Kubernetes knowledge crucial for developers.

- Unfamiliar concepts: Introduces concepts alien to typical developer workflows.

- Learning curve: Mastering these elements demands time and effort.

- Command-line complexity: kubectl requires more than basic command-line skills.

- Increased cognitive load: Understanding the impact of commands within Kubernetes adds complexity.

- Multi-step deployment process: Involves CI/CD pipelines, containerization, manifest creation, and network configuration.

- Focus shift: Deviates from the core objective of building and deploying efficiently.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

kubectl version |

Displays the version of kubectl and Kubernetes API server. |

kubectl get nodes |

Lists all nodes in the Kubernetes cluster. |

kubectl get pods |

Lists all pods in the default namespace. |

kubectl get services |

Lists all services in the default namespace. |

kubectl create -f <file.yaml> |

Creates a resource from a YAML or JSON file. |

kubectl apply -f <file.yaml> |

Applies a configuration change to a resource from a file or stdin. |

kubectl delete -f <file.yaml> |

Deletes resources defined in a YAML or JSON file. |

kubectl describe pod <pod-name> |

Displays detailed information about a specific pod. |

kubectl logs <pod-name> |

Fetches logs from a specific pod. |

kubectl exec <pod-name> -- <command> |

Executes a command inside a container of a pod. |

kubectl scale --replicas=<number> -f <file.yaml> |

Scales the number of replicas for a deployment, replica set, or replication controller. |

kubectl rollout status <resource> |

Watches the status of a rollout until it’s complete. |

kubectl port-forward <pod-name> <local-port>:<remote-port> |

Forwards a local port to a port on a pod. |

kubectl get namespaces |

Lists all namespaces in the Kubernetes cluster. |

kubectl config view |

Displays the current kubectl configuration. |

kubectl config set-context <context> |

Sets the current context in the kubeconfig file. |

kubectl top nodes |

Displays resource (CPU/Memory) usage of nodes. |

kubectl top pods |

Displays resource (CPU/Memory) usage of pods. |

kubectl label <resource> <label> |

Adds or updates a label on a resource. |

kubectl annotate <resource> <annotation> |

Adds or updates an annotation on a resource. |

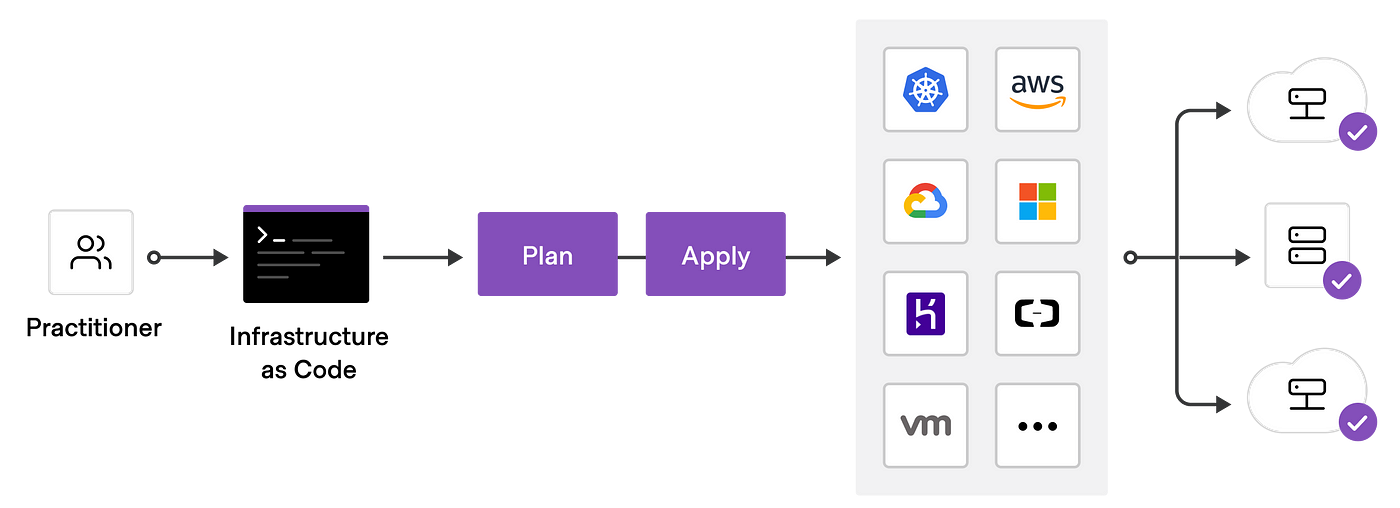

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tools allow you to manage infrastructure with configuration files rather than through a graphical user interface. IaC allows you to build, change, and manage your infrastructure in a safe, consistent, and repeatable way by defining resource configurations that you can version, reuse, and share.

Terraform is HashiCorp's infrastructure as code tool. It lets you define resources and infrastructure in human-readable, declarative configuration files, and manages your infrastructure's lifecycle. Using Terraform has several advantages over manually managing your infrastructure:

- Terraform can manage infrastructure on multiple cloud platforms.

- The human-readable configuration language helps you write infrastructure code quickly.

- Terraform's state allows you to track resource changes throughout your deployments.

- You can commit your configurations to version control to safely collaborate on infrastructure.

Terraform plugins called providers let Terraform interact with cloud platforms and other services via their application programming interfaces (APIs). HashiCorp and the Terraform community have written over 1,000 providers to manage resources on Amazon Web Services (AWS), Azure, Google Cloud Platform (GCP), Kubernetes, Helm, GitHub, Splunk, and DataDog, just to name a few. Find providers for many of the platforms and services you already use in the Terraform Registry. If you don't find the provider you're looking for, you can write your own.

Providers define individual units of infrastructure, for example compute instances or private networks, as resources. You can compose resources from different providers into reusable Terraform configurations called modules, and manage them with a consistent language and workflow.

Terraform's configuration language is declarative, meaning that it describes the desired end-state for your infrastructure, in contrast to procedural programming languages that require step-by-step instructions to perform tasks. Terraform providers automatically calculate dependencies between resources to create or destroy them in the correct order.

To deploy infrastructure with Terraform:

- Scope - Identify the infrastructure for your project.

- Author - Write the configuration for your infrastructure.

- Initialize - Install the plugins Terraform needs to manage the infrastructure.

- Plan - Preview the changes Terraform will make to match your configuration.

- Apply - Make the planned changes.

Terraform keeps track of your real infrastructure in a state file, which acts as a source of truth for your environment. Terraform uses the state file to determine the changes to make to your infrastructure so that it will match your configuration.

Terraform allows you to collaborate on your infrastructure with its remote state backends. When you use HCP Terraform (free for up to five users), you can securely share your state with your teammates, provide a stable environment for Terraform to run in, and prevent race conditions when multiple people make configuration changes at once.

You can also connect HCP Terraform to version control systems (VCSs) like GitHub, GitLab, and others, allowing it to automatically propose infrastructure changes when you commit configuration changes to VCS. This lets you manage changes to your infrastructure through version control, as you would with application code.