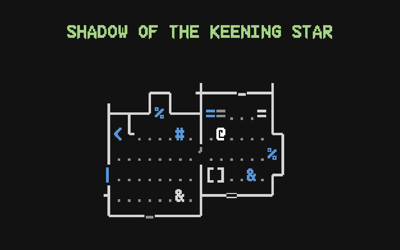

My 2021 entry for the js13kgames competition, Shadow of the Keening Star.

In this retro text-based puzzle adventure game, you've been led to an abandoned New England house by a mysterious letter. Will you find your missing uncle? Or will you end up pulling on the very threads of space and time itself?

Use your arrow keys to explore and interact. Press H in-game for more help.

- Code: Visual Studio Code

- Pixel art (font): Aseprite

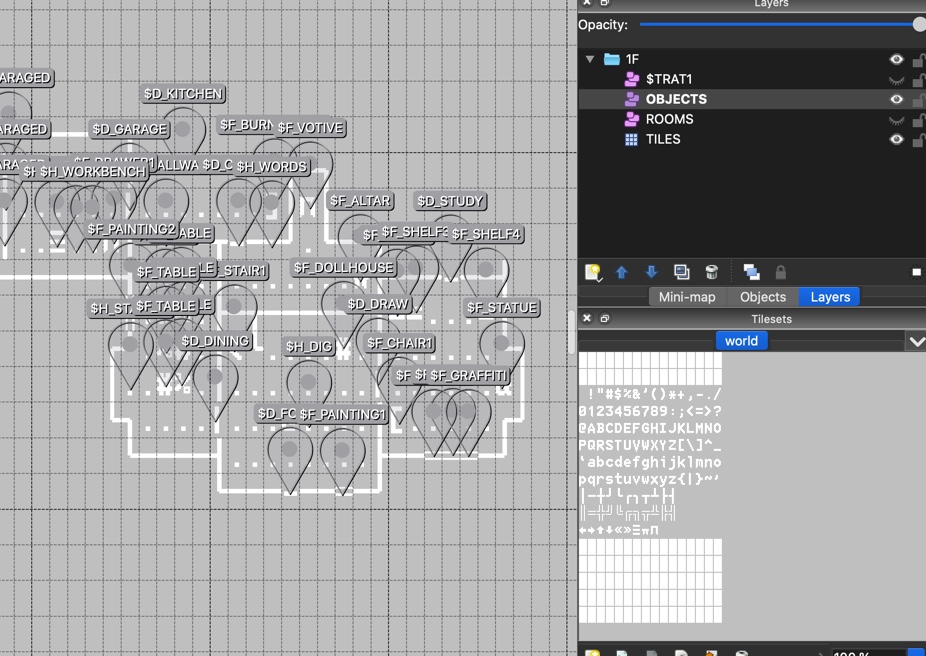

- World (map): Tiled

- Audio (music): PICO-8

To build the game yourself:

npm install

gulp buildTo build with all optimizations and roadroller, for submission:

gulp build --dist(Distribution build takes another ~15 seconds.)

v1.0.0 (2021-09-13)

- Final version for game jam.

It's been bouncing in my head for a couple years now that I wanted to make a very text-based game. Games like Rogue and Kingdom of Kroz are some of my earliest video game memories, and I can't even count the number of hours I spent playing ZZT, beating levels from other players and trying to create my own.

In particular I was really taken with the idea of a game that had the interface and map of a Roguelike, but "narrated" each room you entered and all the actions you took as if it was a text adventure game like Zork. I'm pretty pleased that although the game is much smaller and shorter than I envisioned, I think I did get to make what I wanted.

The story bouncing around in my head was 3-4 times longer than this entry and borrows a lot from Lovecraft's creatures - Azathoth, Yidhra, Nyarlathotep (referred to only as N), etc. Normally the idea would be to let things get progressively stranger, fully leaning into the cosmic horror as you got into the second and third acts. Unfortunately due to space, I really had to only hint at the horror elements that would eventually make up the bulk of the story.

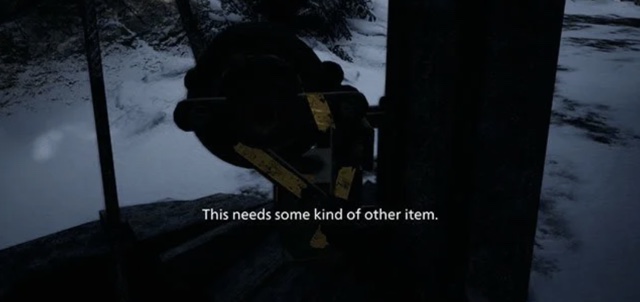

I've been playing a lot of Resident Evil 7 and 8 this past year and surprisingly, that was my biggest inspiration gameplay-wise. For example: originally, you would "move" into objects to pick them up, and "move" into other objects to use anything in your inventory. This seemed streamlined, but it barely felt like a game at all, especially after I had to leave enemies and combat on the cutting room floor.

By always having waiting objects open an inventory screen, I got to do two things -- one, give more chances for players to stumble into and read lore text on items they picked up, and two, give the player the illusion of choice. The player has to CHOOSE to use the iron knife on a door, and even if it's the only and obvious choice, it feels like the player figured something out. (This is a trick Resident Evil uses well I find -- even though almost all doors and mechanisms have exactly one obvious way to use them, you still feel an "aha!" moment when you find the matching key or matching lever and backtrack to use it.)

Another thing I picked up from RE8 in particular was the idea of color-coding interactable objects. By coloring objects you haven't investigated yet as blue, items you've investigated but aren't finished with as yellow, and objects that are no longer interesting as gray, it takes a lot of the guesswork out for the player -- they don't have to remember which shelf they looked at or which doors haven't been unlocked yet. Without the color coding the game would be "harder" -- but only in a way that annoys the player, not in a way that adds any kind of gameplay.

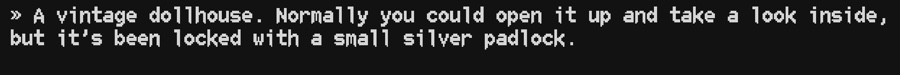

With about a week left in the competition, I realized I had to make some deep cuts, and I chose to implement an actual story-based introduction (welcome screen) and outro (goodbye screen), and to connect the puzzles together a little more, making a very short but consistent adventure game. I had to drop the "hit and miss" D&D combat I had planned, as well as plans for other types of puzzle mechanics (classics like: interact with these objects in the right order, stand on the pressure plate, unlock a padlock by finding the right code, etc.). My reasoning was that for sure there will be much better puzzle games than this one, and for sure there will be games with much better combat; so, I'll lean into the story (text) aspect of this game, because that's what makes it unique.

To emulate the old text-mode games, I wanted a classic 8x16 pixel font -- but ideally with a little horror character. After searching for quite a while, I stumbled into Robey Pointer's Bizcat font (CC4.0), which struck me as just about perfect -- adding a few pixels here and there to vertical lines in all the letters gives the text a jagged, uneven feel that would look at home in a game about vampires -- or in my case, cosmic horror.

For fun I named my variant "Bizcat Knife", due to its more jagged appearance, although I'm not sure I'll get to use it again. (Typically your font is vying with your other art assets for space, and 8x16 for every character is a lot of art, 4x5-5x6 is more typical for a pixelated font in js13k.)

I learned an incredible amount (mostly about what not to do) while trying to build out the world for this game. This year for map building I went back to Tiled. In the screenshot below you can see that I can use my font sheet to "paint" the world using my custom font as tiles, and then on top, I can lay the positions of rooms and objects.

Unfortunately, I found editing text in Tiled a bit annoying, especially with text like I was writing -- multi-line descriptions

of items where I often wanted to control the exact spacing of each line. So instead, I created a

giant YAML file

containing all the strings in the game. In my workflow I'd add an entry in the YAML file for a new thing (perhaps $F_STATUE),

then in Tiled I can decide where I want $F_STATUE to go on the map. Having all the text in one big file like this definitely

made it easier to search, and I'd often write out the descriptions of a room and everything in it and then sort them into

individual entries.

As for how objects behaved, I went very low-tech -- almost everything about the gameplay is in a big

series of if statements in the Player class. Near the end I began experimenting with categorizing objects so I didn't have

to add them into the big logic method -- a TYPE_EXAMINE_ONLY type, for example, meant you just looked at it and that was it.

A next step might be to code up more common interactions -- for example, a very common pattern is "interact with door,

interact with door again to open inventory, pick the right item and the door opens". Having a type LOCKED_DOOR, with a

value for required_item: $I_IRON_KNIFE, could also reduce some if statements.

This year I did something totally different with audio. Instead of using the ZzFX & ZzFXM libraries, I used Cody Ebberson's pico8-music library. I wrote my song in the PICO-8 music tracker, and then in my gulp build, it transforms it into a little JS module that can be used in-game.

I really enjoyed this process; there's some really nice tutorials out there already on making music in PICO-8, as it's a relatively popular retro game maker, and it was fun to play around in the retro sfx and music editor.

There are some cons: there's still some bugs with the library (I was never quite able to get sound effects working right, for example, and did not end up including them), and technically the PICO-8 sfx and music system is more restrictive than ZzFX. But with a little more experimentation I can definitely see it being an option for future js13k games.

Fitting this much text into a 13 kilobytes proved to be pretty difficult. At this point I'm an old hand at space-cutting measures, but I did learn a couple new ones this year.

I started out having object id's as strings, which eats a lot of space, because those raw identifiers like DRAWING_ROOM

are all in your final code. To avoid this, I ended up giving the IDs special names like $D_CLOSET and then wrote a

custom build step that would let terser mangle all my names, and then replace any strings with the same names with

the mangled values. However, in the end, I stumbled upon a much better way -- I ripped out this use of the terser

name cache and instead I generate export constants for all my object ids in my generated WorldData file. This

is even better because since the constant $D_CLOSET now has the constant value 46, terser can actually remove

the variable altogether and just insert the number 46 anywhere it was used. This was a big space saver.

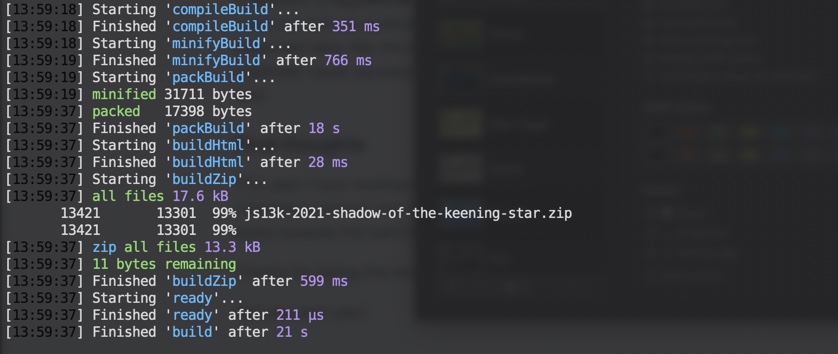

In addition to aggressive property mangling and the above object id trick, for the last 1000 bytes of space or so, I ended up adding roadroller into my build and it worked like a charm. I tried several different ways of manually compressing / streamlining some of my patterned data, like the audio music tracks and the map tile data, but typically my efforts would net me maybe 50-100 bytes back, whereas roadroller could squeeze out another 1000 bytes. It turned out better to just let roadroller take care of the final "packing" -- it's an impressive tool!

This year I have newfound appreciation for video game writers. It turned out that painting the kind of slow, skittering descent into horror that I wanted to portray was just as hard with words as it was with pixels. Plus the added pressure that every word I added was another couple bytes towards the hard limit. So good on you, video game writers!

Thanks for taking the time to try out my game, and if you've made it this far, for reading this post-mortem.

See you next year!