I found that there actually exists very few tutorial-like resources on how to use Raspberry Pi's DMA channel properly. There are some code examples, but they take time to read and may be tough for beginners to understand.

So I wrote this article for those who need to control DMA channels themselves, or (like me) are just curious about how great tools like pigpio achieves high-speed sampling while consuming surprisingly low CPU resources. I'm not an expert in Raspberry Pi, so I welcome any comments or suggestions so that I can improve this tutorial.

In this tutorial, we will first control the DMA to continuously fetch the BCM2835 system timer, then we attempt to pace DMA accesses with the PWM peripheral so we can designate a fixed sample rate. I choose the system timer here because it increments every microsecond, so we can easily check whether our code is working correctly. Finally, I'm going to present a demo that uses DMA to monitor GPIO level changes at the accuracy of 1 us.

I tested my code on my Raspberry Pi 3 B+, but it seems that the only difference across models is the base address of peripherals. Although this article focuses on sampling (reading), it should be as simple as swapping src and dest to let the data flow reversely.

As described in BCM2835-ARM-Peripherals (the "datasheet"), There are three types of addresses in Raspberry Pi:

- ARM Virtual Address: The address used in the virtual address space of a Linux process.

- ARM Physical Address: The address used when accessing physical memory. Since peripherals on BCM2835 are memory-mapped, this address is used to access peripherals directly.

- Bus Address: This is the address used by the DMA engine.

The physical addresses of the peripherals range from 0x3F000000 to 0x3FFFFFFF and are mapped onto bus address range 0x7F000000 to 0x7FFFFFFF. We can convert between them like this:

#define BUS_TO_PHYS(x) ((x) & ~0xC0000000The BCM2835 has 16 DMA channels. The DMA channel controller registers start at bus address 0x7E007000, with adjacent channels offset by 0x100. Detailed information about the DMA controller can be found in Section 4 of the datasheet.

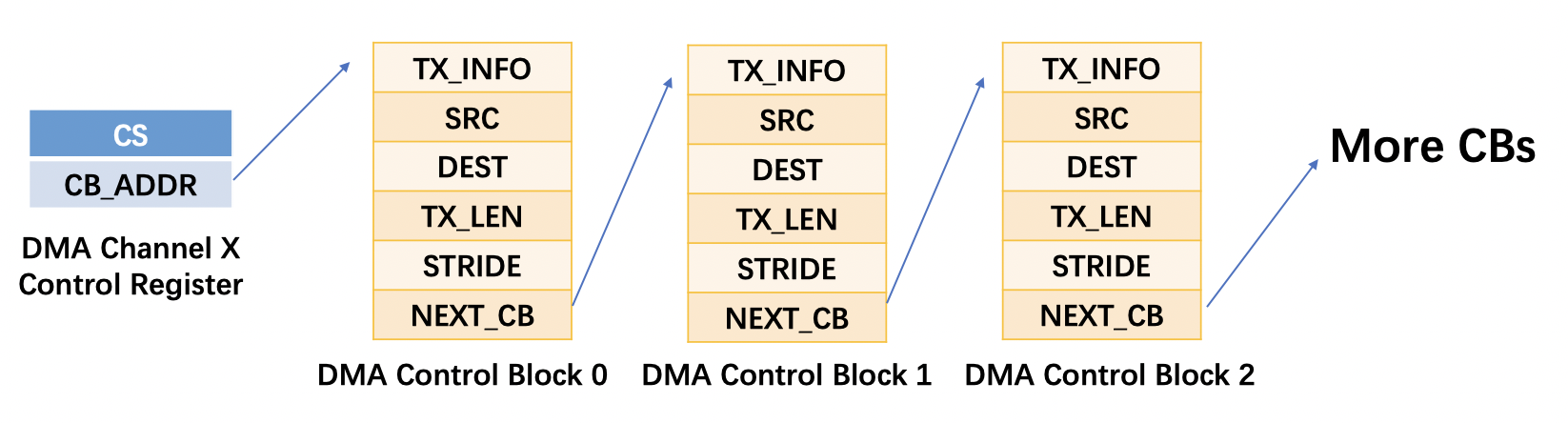

The DMA control blocks on BCM2835 are organized as a linked list, with the sentinel being DMA channel controller register. When DMA starts working, the cb_addr field is updated after each DMA transfer so it always point to the current control block. Note that all "pointer"s in the following graph are bus addresses. The exact meaning of these registers are documented in Section 4.2.1 in the datasheet.

The first thing is to get access to the peripherals. As memtioned above, peripherals can be accessed by user programs with their physical address. In order to configure the DMA channel, we need to bring the DMA controller registers into virtual memory.

The way we access these memory-mapped peripherals is to mmap them from the /dev/mem device, which is an image of main memory. I wrapped this procedure in a function, note that I omitted error handling code here for clarity.

void *map_peripheral(uint32_t peri_offset, uint32_t size)

{

// Error handling omitted for clarity, see full code in dma-unpaced.c

// Check mem(4) man page for "/dev/mem"

int mem_fd = open("/dev/mem", O_RDWR | O_SYNC);

uint32_t *result = (uint32_t *)mmap(

NULL,

size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED,

mem_fd,

PERI_PHYS_BASE + peri_offset); // PERI_PHYS_BASE defined as 0x3F00000

close(mem_fd);

return result;

}With this defined, we can obtain pointers to peripherals. Also, remember to use volatile when accessing peripherals!

volatile uint8_t *dma_base_ptr = map_peripheral(DMA_BASE, PAGE_SIZE);

// We use DMA channel 5 here, so a little pointer arithmetic is required

volatile dma_channel_hdr = (DMAChannelHeader *)(dma_base_ptr + DMA_CHANNEL * 0x100);The next step is to allocate our control blocks and a buffer to store DMA results. What's special about this is that since DMA accesses uses bus address, we need to find a way to know the bus address of our allocated memory region.

As bus addresses can be calculated from physical addresses, a straightforward way to get physical addresses out of virtual addresses may be using Linux's pagemap interface. However, this seems to be reliable because we can't guarantee the memory we have is cache coherent, which is crucial to proper DMA. Also, the exact physical address backing a certain virtual address may be subject to change. Thus, I do not recommend using pagemap.

What comes to the rescue here is the mailbox property interface. As it's developed for communication between the ARM and the GPU, which I guess also suffers from cache coherency problems, it provides ways to allocate contiguous memory on the coherent portion of L2 cache & RAM and lock it on a fixed bus address. It looks perfectly suitable for DMA, so it's becoming a standard way for projects adopting DMA. We are gonna use it, too.

We use an abstraction to represent a memory block.

typedef struct DMAMemHandle

{

void *virtual_addr; // Virutal base address of the memory block

uint32_t bus_addr; // Bus address of the memory block

uint32_t mb_handle; // Used internally by mailbox property interface

} DMAMemHandle;I've included a mailbox implementation in this repository that's copied from here. Inspired by hezller's demo, we can use mailbox to implement malloc and free-like memory management. You may need to check its permissive license if you are to use it.

// mailbox_fd initialized with mbox_open()

DMAMemHandle *dma_malloc(unsigned int size)

{

// Make `size` a multiple of PAGE_SIZE

size = ((size + PAGE_SIZE - 1) / PAGE_SIZE) * PAGE_SIZE;

DMAMemHandle *mem = (DMAMemHandle *)malloc(sizeof(DMAMemHandle));

mem->mb_handle = mem_alloc(mailbox_fd, size, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_FLAG_L1_NONALLOCATING);

mem->bus_addr = mem_lock(mailbox_fd, mem->mb_handle);

mem->virtual_addr = mapmem(BUS_TO_PHYS(mem->bus_addr), size);

mem->size = size;

return mem;

}

void dma_free(DMAMemHandle *mem)

{

unmapmem(mem->virtual_addr, mem->size);

mem_unlock(mailbox_fd, mem->mb_handle);

mem_free(mailbox_fd, mem->mb_handle);

mem->virtual_addr = NULL;

}With all these defined, we can easily allocate our memory.

dma_cbs = dma_malloc(CB_CNT * sizeof(DMAControlBlock));

dma_ticks = dma_malloc(TICK_CNT * sizeof(uint32_t));Now that we have finished our preparation, we can finally initialize the DMA control block linked list. Here is the code for setting up the ith control block:

DMAControlBlock *cb = ith_cb_virt_addr(i);

cb->tx_info = DMA_NO_WIDE_BURSTS | DMA_WAIT_RESP; // A normal DMA block

cb->src = PERI_BUS_BASE + SYSTIMER_BASE + SYST_CLO; // Bus address of the lower word of system timer

cb->dest = ith_tick_bus_addr(i); // The ith location in our result buffer

cb->tx_len = 4; // 32 bits = 4 bytes

cb->next_cb = ith_cb_bus_addr((i + 1) % NUM_CBS); // A circular list here to do DMA foreverAfter that, let the DMA controller register to point to the first DMA control block and set the active bit in the CS field to start DMA transfer.

dma_reg->cb_addr = ith_cb_bus_addr(0); // Point to the first control block

dma_reg->cs = DMA_PRIORITY(8) | DMA_PANIC_PRIORITY(8) | DMA_DISDEBUG; // Sets AXI priority level

dma_reg->cs |= DMA_WAIT_ON_WRITES | DMA_ACTIVE; // Start DMA transferYou could find the code until now in dma-unpaced.c. Compile it with make dma-unpaced. We need sudo privilege to run the program as we are directly manipulating physical memory. Now that the DMA starts, we could see the results of 20 consecutive reads to the system timer. On my Pi, the output happens to be:

$ sudo ./dma-unpaced

Init: 20 cbs, 20 ticks

DMA 0: 1616166277

DMA 1: 1616166277

DMA 2: 1616166278

DMA 3: 1616166273

DMA 4: 1616166274

DMA 5: 1616166274

DMA 6: 1616166274

DMA 7: 1616166274

DMA 8: 1616166275

DMA 9: 1616166275

DMA 10: 1616166275

DMA 11: 1616166275

DMA 12: 1616166276

DMA 13: 1616166276

DMA 14: 1616166276

DMA 15: 1616166276

DMA 16: 1616166276

DMA 17: 1616166277

DMA 18: 1616166277

DMA 19: 1616166277

It seems that the speed of DMA accesses to the system timer is about 4~5 MHZ, which is decent. However, most of the times we hope to do DMA accesses at timed intervals, so we can control the sampling rate. Fortunately, we could do this by pacing DMA accesses with its DREQ mechanism (documented in Section 4.2.1.3 in the datasheet), although it's a little tricky.

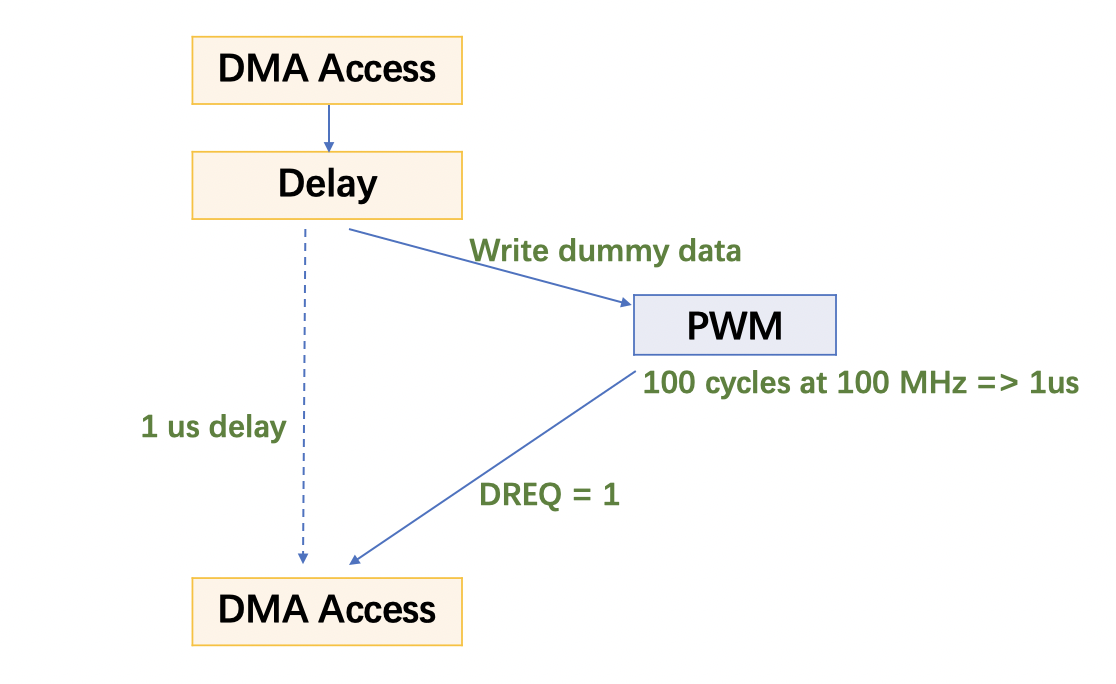

We do this by inserting a "delay" block between two normal DMA blocks. The idea is: the "delay" block invokes a DMA write to the PWM FIFO. Then the PWM controller reads from its FIFO and "sends" this data to its own output, during which the DMA keeps waiting until PWM sets the DREQ signal to high. As we could control the number of clock cycles the PWM controller spend sending the data, we could delay the DMA for the duration we want.

You could see that exactly what data to be sent to the PWM FIFO doesn't really matter. We just use PWM to generate an accurate delay. If you are unclear of how the PWM controller works, check Section 9.4 of the datasheet. Also note that PCM can basically do the same thing, but we'll use PWM for this tutorial. Another thing to notice is that the clock mentioned last paragraph is the clock generated by the clock manager, which is documented in Section 6.3 of the datasheet . I recommend also checking here for its register mappings.

In my example, I choose the 500-MHz PLLD here as our PWM clock source, as it's unlikely to change across models. I divide it by 5 to get a 100-Mhz clock and set range field of PWM controller to 100 so it takes 100 clock cycles to send the data, which forces the DMA to wait for a duration of 1 us.

Here is a simplified version of the code used to control the PWM.

clk_reg->ctrl = BCM_PASSWD | CLK_CTL_SRC(CLK_CTL_SRC_PLLD); // Clock source

clk_reg->div = BCM_PASSWD | CLK_DIV_DIVI(5); // Divide by 5, 100 Mhz now

clk_reg->ctrl |= (BCM_PASSWD | CLK_CTL_ENAB); // Enable the clock

pwm_reg->range1 = 100 * 1; // Sending for 100 cycles

pwm_reg->dma_cfg = PWM_DMAC_ENAB; // Enable PWM DMA

pwm_reg->ctrl = PWM_CTL_CLRF1; // Clear PWM FIFO

pwm_reg->ctrl = PWM_CTL_USEF1 | PWM_CTL_MODE1 | PWM_CTL_PWEN1; // Enable PWMConfiguring the "delay" control block is roughly the same as a normal block, except for the following fields:

cb->tx_info = DMA_NO_WIDE_BURSTS | DMA_WAIT_RESP | DMA_DEST_DREQ | DMA_PERIPHERAL_MAPPING(5); // Tell DMA to use DREQ

cb->src = ith_cb_bus_addr(0); // Dummy data

cb->dest = PERI_BUS_BASE + PWM_BASE + PWM_FIFO * 4; // Send to PWM FIFOThe complete code with paced DMA accesses can be found in dma-paced.c. You can make dma-paced and run the program:

$ sudo ./dma-paced

Init: 40 cbs, 20 ticks

DMA 0: 2855359907

DMA 1: 2855359908

DMA 2: 2855359909

DMA 3: 2855359910

DMA 4: 2855359911

DMA 5: 2855359912

DMA 6: 2855359913

DMA 7: 2855359914

DMA 8: 2855359915

DMA 9: 2855359916

DMA 10: 2855359917

DMA 11: 2855359898

DMA 12: 2855359899

DMA 13: 2855359900

DMA 14: 2855359901

DMA 15: 2855359902

DMA 16: 2855359903

DMA 17: 2855359904

DMA 18: 2855359905

DMA 19: 2855359906

We could see that the DMA accesses are done precisely once a microsecond, cool!

Now that we're able to do our DMA accesses at a fixed sampling rate, we could do something more useful than checking the system timer. In this final example, I present a demo that uses literally the same DMA technique introduced in last section to watch the levels of GPIO 0-27 with a sample rate of 1 us and on detected level change, report the new GPIO levels as well as when (in us) the level change took place. The code can be found at dma-demo.c.

A main loop wakes up every 5 ms to process those GPIO levels that has been recently sampled into the ring buffer. In case the process would be switched out by the Linux scheduler for a long time, I allocated a huge buffer that could store samples in the last 100 ms. The ring buffer is accessed in a straightforward way:

// `old_idx` is the index of the latest `level` record we have processed

// `cur_idx` is the index of the latest `level` record the DMA engine have sampled

while (1)

{

cur_idx = get_cur_level_idx(); // We can caluculate the current level record index by current DMA CB index

while (old_idx != cur_idx)

{

uint32_t level = *ith_level_virt_addr(old_idx) & ~0xF0000000; // Only GPIO 0-27

if (level != cur_level)

{

printf("Level change @%u: %08X\n", cur_time, level);

cur_level = level;

}

cur_time += CLK_MICROS; // It will wrap around itself

old_idx = (old_idx + 1) % LEVEL_CNT; // LEVEL_CNT is total num of samples in the buffer

}

usleep(SLEEP_TIME_MILLIS * 1000); // SLEEP_TIME_MILLIS is 5, but could be smaller

}I noticed that the cumulative error of PWM-generated delays in one second could be more than ten microseconds. So I inserted one timestamp, after every 50 accesses to the GPLEV0 register to correct this error.

Now compile this code with make dma-demo and run with sudo ./dma-demo, then if you have pigpio installed, open another terminal and try toggling one of the GPIOs:

>>> import pigpio

>>> pi = pigpio.pi()

>>> pi.write(4, 1)

>>> pi.write(4, 0)You could see that the level changes are detected immediately as you type in the python commands! Also check htop and on my machine, the CPU usage of our demo program is just as low as around 20%. With a lower sample rate like 5 us, the CPU usage is almost negligible.

As is mentioned at beginning of this article, there are lots of great code examples that use DMA. pigpio is the one that use most, and it provides DMA memory allocation implementaions using both pagemap and mailbox, as well as DMA delay implementations with both PCM and PWM. I haven't used ServoBlaster before, but it is probably the first to use PWM to generate accurate DMA delay, and this stackoverflow post may help you understand its code. Wallacoloo's example (a bit outdated) and hezller's demo are also great references. The ideas in this article is largely based on the above resources and explained according to my own understanding.