Cruel fist fights, brutal killings, rough sexual assaults - movies sometimes show more explicit violence than we would like. But do they lead to an increase in real-world violence? Or, on the contrary, do they serve as a release that reduces it? This study analyzes 17077 movies from the CMU Dataset 1, enriched with data from the Kaggle Movies Dataset 2. Using this data in combination with the NIBRS dataset 3 and the GVD dataset 4, we examine the correlation between depicted violence in movies and real-world violence in the US. To purge the analysis from potential other factors that influence the real world violence, we will use an auto-regressive distributed lag model with time fixed effects. This will allow us to draw valid conclusions from the correlation analysis in order to answer our research questions.

Even if very few would have believed it 20 years ago, wars and violent political conflicts are once again present. Moreover, everyday violence seems to be on the rise worldwide, as a study on the perception of violence in one's own neighborhood states 5. This underlines the importance of violence as the overall subject of this study. Within our analyses we aim to provide answers on the following research questions:

- Is there a significant (positive or negative) correlation between the prevalence of violent movies and reported violent crimes in the US?

- Can we identify periods of abnormally many releases of violent movies?

- Can we identify genres that are particularly violent?

The focus on the geographical area of the US is due to the fact that there is most data available, both for the movies and the real-world violence.

The central dataset for our study is the CMU Dataset 1. Since time will play a crucial role in our study and precise release dates are often unavailable, we will fill in missing dates dates using The Movies Dataset from Kaggle 2. The first step is to clean and filter the movie data as follows:

- Removing unnecessary columns and NaN entries

- Keep only the entries for which we have both metadata and a plot summary

- Lowercase all plot summaries

- Convert all entries in easily readable format (e.g. convert {"/m/09c7w0": "United States of America"} to "United States of America")

- Filter only for US movies

Incomplete or missing dates for movies in the CMU dataset are replaced with corresponding data from the Kaggle dataset (matched based on movie titles and date comparisons). If neither the CMU nor the Kaggle dataset provide valid information on the movie date, we drop the corresponding entry. The cleaned dataset is exported and saved in .tsv format.

The next step is to identify the violent movies in the cleaned dataset. We want to distinguish between the following three classes:

- Violent

- Mildly violent

- Non-violent

To achieve this, we implemented two different models:

- Model 1: Multiclass logistic regression model trained by us

- Model 2: Pre-trained LLM

Here, we first compute three different scores based on the plot summaries:

- Physical violence score

- Psychological violence score

- Sentiment scores

For the physical and psychological violence score, we identified two separate lists of words that are unambigously connected to physical and psychological violence respectively. For potential further interest in the justification for those words, we created two .txt files in the data > CLEAN > violent_word_list folder.

We parse through all plot summaries in the cleaned data and count how often those words appear. Since the length of the plot summaries varies significantly, we additionally compute the "density" of physical and psychological words by dividing the absolute counts by the number of words in the plot summary.

For the sentiment scores, we apply the DistilBERT model trained for sentiment analysis 6. This model also parses through all plot summaries and computes scores for the following five sentiments: sadness, joy, love, anger, fear, surprise. The higher the score, the more prevalent is the sentiment.

Those three scores are the features for the model. It is trained on a set of movies that we labelled by hand using the crowdsourcing approach, i.e. by activating our own social network. Model 1, however, showed unsatisfying results, since our features do not seem to sufficiently capture the complex notion of violence.

Here, we use a pre-trained LLM (mini-GPT4) with custom prompts, our three different violence classes and a set of instructions. The assessment of the model performance is done on the same human-labelled movies as before. Due to the subjectivity of the human labelling process, model performance evaluation is yet not trivial. Generally, the performance of Model 2 is significantly better than Model 1. Thus, the cleaned dataset labelled by Model 2 will be used for the correlation analysis.

For real-world violence, we rely on two datasets:

The offense_type_id feature in NIBRS determines whether a crime qualifies as violent. While GVD helps track broad trends, NIBRS supports granular temporal analysis.

A simple linear regression of violent movies on violent crimes would overlook confounding factors. To address this, we will implement an auto-regressive distributed lag model with time-fixed effects, offering the following advantages:

- Fine temporal resolution: Analyzing daily or monthly data captures immediate effects of violent movie releases.

- Time-fixed effects: Absorbs macro-level influences like wars or riots.

- Auto-regressive lag: Accounts for the persistence of violence over time.

This approach will allow us to isolate the specific impact of violent movies on real-world crime.

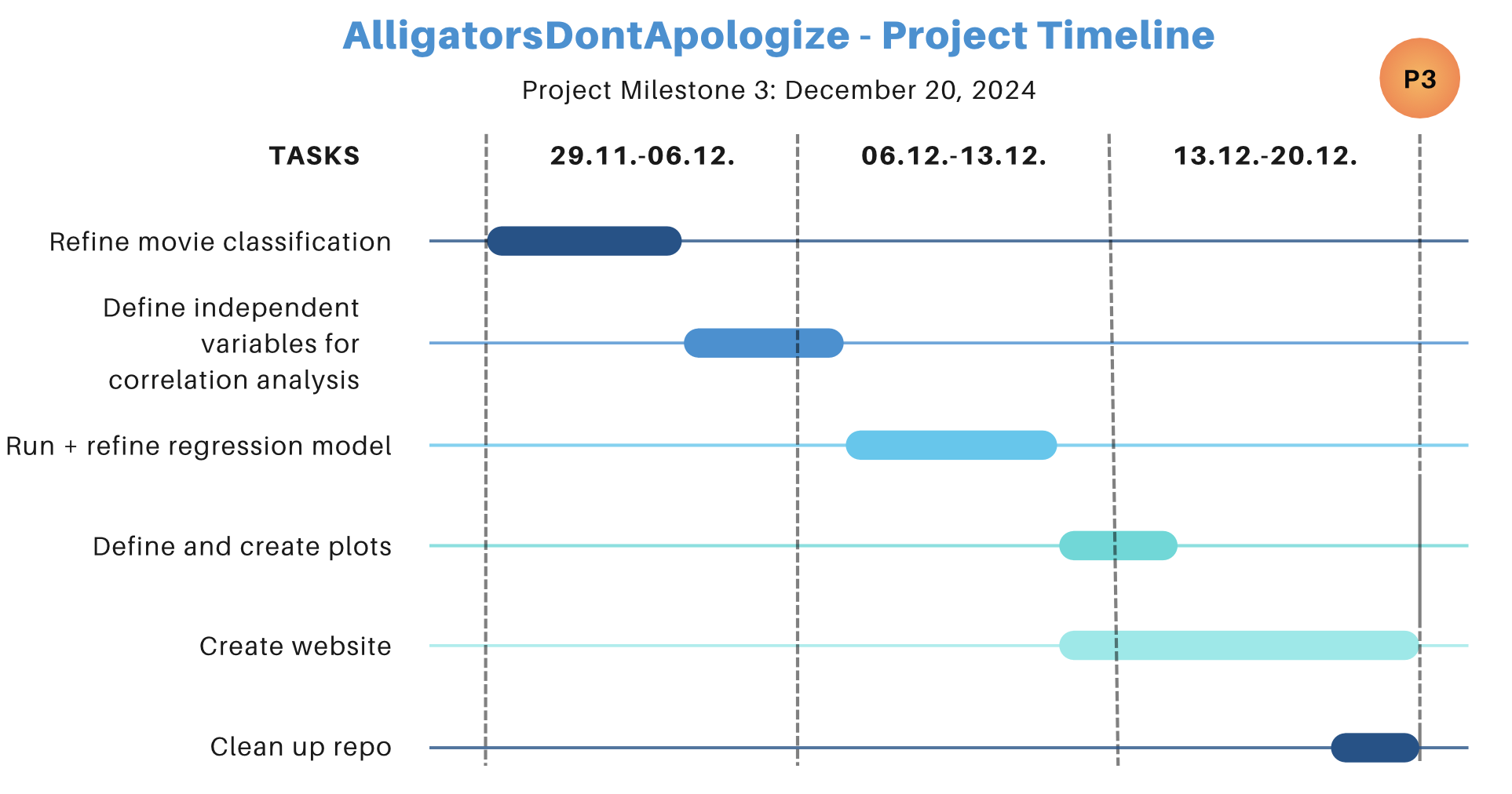

The proposed further timeline for our project is the following:

The list of tasks until P3 mentioned in the picture above are equally shared within the team to ensure that every team member contributes to the project.

Footnotes

-

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rounakbanik/the-movies-dataset ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.dolthub.com/repositories/Liquidata/fbi-nibrs/data/main ↩ ↩2

-

Jackson, Chris. Views on Crime and Law Enforcement Around the World, Ipsos, 2023. ↩

-

https://huggingface.co/bhadresh-savani/distilbert-base-uncased-emotion ↩