Since CAM2 is heading into some heavier development, I’d like to talk about a few things that could help smooth over the transition. Assuming most people reading this haven’t had a lot of experience writing code with other people, the purpose of this document is to get small things out of the way so PRs can focus on the larger problems.you

Python uses something called snake case. It means instead of writing something in camelCase you would write it in snake_case. Generally, lowercase everything. The only times you violate this rule is in Class names, where you would use CapCase.

# How not to write a function and variable

def ThisIsBad():

badVariable = "bad variable"

# How to write a variable

def this_is_good():

good_variable_name = "this is good!"Another thing is to never abbreviate things in Python. Things are confusing enough with the lack of typing* and everybody working on different parts of the program. Part of what makes Python great is readable code to the human eye, so make sure you’re naming variables and functions in a descriptive way rather than something that is convenient (because in the future it will make things convenient!).

# Do not name variables like this

x = 3

# What does x do? Nobody knows. Instead, name variables like this:

pool_thread_limit = 3

# Nice and descriptive! Now we know that pool_thread_limit limits the number of threads!Source: PEP 8

Python has supported type hinting since version 3.5. What this means is we can effectively communicate what the type of the return value is and what the type of the variable is. With type hinting, we can avoid having to deal with incompatible type errors, or for objects, class attribute and function does not exist errors. Here’s how we do that.

from random import randint

def be_happy(day: str, coffee: bool=False) -> bool:

if day == "Monday":

return False

else:

luck: int = randint(0, 10)

return (luck > 5) and coffeeLet’s break down what just happened. I used type hinting in the arguments of the function. I added some arrow-looking thing pointing towards a type at the end of the function I added a colon and type between the variable and value in line 7.

In order to represent the type a variable is meant to be, we use the colon and type value. When we want to represent the return type of the function, we use the arrow like I did in line 3.

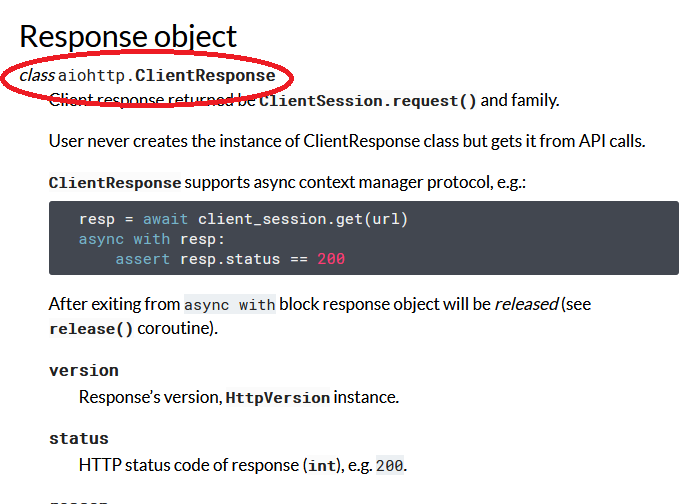

It can be hard to discern the true type of an object, especially if it’s from an external library. A good way to do this is to pull up the documentation for the library and take a look at the marked section below. This section will appear if the library has been properly documented (aka using Sphinx).

Another way to discern the type is to use the type method. Open up a Python interpreter under the same virtual environment, import the library, create the object you want and assign it to a variable, then use the type function.

from quart import Quart

app = Quart("name")

print(type(name))

#outputs <class 'quart.app.Quart'>Source: PEP 484

Yeah sure, we’re software engineers, not journalists or editors at newspapers. This just means documenting code and describing our code is that much important, and grammar is a really big part of that. If we have problems communicating the purpose of our code between ourselves, it’ll be even harder to present it at a midway checkpoint or something. Here are a few grammar things to look out for that will keep our work looking professional: Capitalization: It’s as simple as pressing the shift button when you start the sentence! Also consider the visual difference between the following:

# creates a neural network to analyze the code

# Creates a neural network to analyze the code.Spelling is also important.

Docstrings are a powerful way to document your Python code. This is important so developers who both maintain and add to our code in the future can understand what we did and how it works. First, let's understand the anatomy of a docstring. This will help us write good docstrings and understand docstrings written by others.

At the top of every docstring should be a simple one sentence description of what your function / class does. If you can’t describe in one sentence then it probably does too much.

def get_emotion(day: str) -> str:

"""Gets the emotion based on the day.

"""

if day == "Monday":

return "Sad"

else:

return "Happy"Notice the use of good grammar and punctuation here as well. Both of those are essential parts of a good docstring.

Not every function or class can be described in one sentence and that’s okay. If you need to tell the person using your function about an edge case, undefined behavior or other details about your implementation this is the place to do it.

def get_emotion(day: str) -> str:

"""Gets the emotion based on the day

The parameter day is a case sensitive variable. This means that "Monday"

will not register as "Monday."

"""

if day == "Monday":

return "Sad"

else:

return "Happy"Some functions are going to use parameters and like everything else a docstring is the perfect place to document it. When describing parameters we want to keep it brief. The goal is to give the developer context to what value the parameter should be and why this function needs it.

def get_emotion(day: str) -> str:

"""Gets the emotion based on the day

The parameter day is a case sensitive variable. This means that "monday" will not

register as "Monday."

Args:

day (str): The day of the week you want to get the emotion for.

Raises:

ValueError: The day of the week passed is not defined.

Returns:

str: The computed emotion in CapsCase.

"""

if is_not_valid_day(day):

raise ValueError("Invalid day passed. This could be a spelling error.")

if day == "Monday":

return "Sad"

else:

return "Happy"A few things changed here. We added a new subsection “Args”. This is so we can easily find where the parameters are documented. Next we added the parameter itself “day” for each parameter there are 3 parts. The name of the parameter “day”, the type of the parameter “str” and the description of the parameter. Docstrings should contain all three parts.

Like most programming languages, Python lets us report errors and exceptions. This is a great tool and should be used. Documenting them is very similar to arguments like we did above in section 4.3. Like arguments the goal is to give the developer information on what errors and exceptions might be raised and why they might be raised.

def get_emotion(day: str) -> str:

"""Gets the emotion based on the day

The parameter day is a case-sensitive variable. This means that 'monday' will not register as "Monday".

Args:

day (str): The day of the week you want to get the emotion for.

Raises:

ValueError: The day of the week passed is not defined.

"""

if is_not_valid_day(day):

raise ValueError("Invalud day passed/ This could be a spelling error.")

if day == "Monday":

return "Sad"

else:

return "Happy"This is the final part of the docstring for methods. It is also one of the most important parts of the method docstring. By providing a context to your methods return value, developers who use your method will be able to use the return information properly. This will reduce the chance of them introducing any bugs into their code.

def get_emotion(day: str) -> str:

""" Gets the emotion based on the day

The parameter day is a case-sensitive variable. This means that "monday" will not register as "Monday".

Args:

day (str): The day of the week you want to get the emotion for.

Raises:

ValueError: The day of the week passed is not defined.

Returns:

str: The computed emotion in CapCase.

"""

if is_not_valid_day(day):

raise ValueError("Invalud day passed/ This could be a spelling error.")

if day == "Monday":

return "Sad"

else:

return "Happy"Notice the similarities? Like the Errors section we only need to denote a type, and like both the Errors and Parameters section we give a short description of the developer calling this function should expect it to return.

If you follow the proper naming scheme and type hinting in sections 1 and 2, then your code is probably fairly readable. So why do we need comments? The short answer is readability. While it might be apparent to the reader what your function does, sometimes we need to explain why we did certain things like why a hardcoded value is 8 or 29. Let’s take a look at a few examples.

def connect_to_clent(hostname: str, port: int) -> None:

server = get_current_server()

# Flushes the server port

server.flush(port)

server.close(port)

server.reset(port)

server.bind(hostname, port)This is a bad example of a comment. All our comment did was reiterate the name and parameter of our function. Our code would be readable without it.

def connect_to_clent(hostname: str, port: int) -> None:

server = get_current_server()

# Clears port so next connection doesn't received partial or full packces

# not meant for it.

server.flush(port)

server.close(port)

server.reset(port)

server.bind(hostname, port)This comment is much better. Rather than tell us what it does, it tells us why we need it. This is important because a future developer might have assumed that close or reset handled this. Now we know both why this function exists and the consequences of removing it.

git remote add [label] [remote_url]

git remote add upstream git@github.com:flutter/flutter.git

# Now the main Flutter repo is a remote for our repo now!The label is the name you will be assigning to the url.

git fetch [label]

git fetch upstreamWhere label is the remote to get the latest version from (Note: this will not affect your current work).

git rebase [label/branch]

git rebase upstream/masterWhere label/branch is the remote/branches commits to apply before the commits on your local branch (this should be run before and after you add commits to your repository to reduce the chance of merge conflicts.

Source: Thoughtbot