Global lake-terminating glacier classification: a community effort for the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) and beyond

Written by William Armstrong and Tobias Bolch with contributions from Robert McNabb, Rodrigo Aguayo, Fabien Maussion, Jakob Steiner, and Will Kochtitzky

Knowledge about the existence of lakes which are in contact with glaciers is a fundamental importance to understand as the lakes increase glacier mass loss due to calving, dynamic thinning and increased mass loss at the ice-water interface (e.g., King et al. 2019; Tsutaki et al. 2011; 2019; Pronk et al. 2021). Moreover, they impact geodetic mass balance calculations as satellites cannot measure subaqueous mass loss (Zhang et al. 2023).

The main aim of this effort is to determine whether a glacier is lake-terminating for the general attribute table of the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI). Uncertain (in case the existence is possible but cannot be determined due to unsuitable images) or specific cases (e.g. if a lake is only in contact with a small part of the lake termini) shall also be documented. In cases where a glacier is found to be lake-terminating, we seek to provide a qualitative “connectivity level” evaluation (akin to Rastner et al., 2012) that users can further parse depending on their needs.

Secondary aims that can partially addressed with this inventory are a classification of morphologies of lake-terminating versus non-lake-terminating glaciers and the provision of a baseline to identify hotspots where cryosphere risks related to potentially expanding lakes (e.g. glacial lake outburst floods) as well as changing aqueous ecologies should receive future attention.

These illustrated guidelines will describe the general methodology and provide information about how to decide whether a glacier is lake-terminating and how to assess connectivity level to provide consistent attribution for the RGI table.

For determining whether a glacier is lake-terminating, your guiding question should be “does the glacier end in a lake(s) large enough to have the potential to significantly increase the glacier’s mass loss and/or alter glacier dynamics?”. This is an inherently subjective determination, and we have developed three confidence levels (described below) to promote consistent determination of lake-terminating status across contributors. If you answer “definitely”, “probably”, or “possibly” to the question above, you will place it in one of the lake-terminating glacier confidence levels. If you answer “no” or “not likely”, this glacier should be considered land- or marine-terminating.

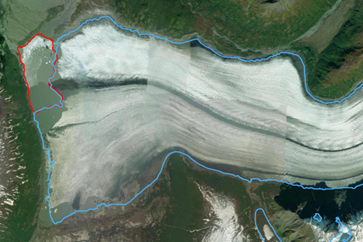

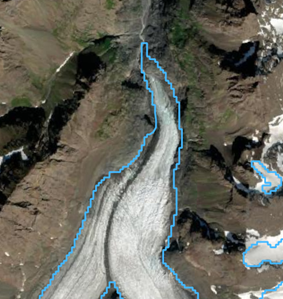

The glacier is definitely in direct contact with a large lake that spans at least ~50% of the glacier terminus. Lakes smaller than 0.01 km2 should not be considered. Glaciers in this lake-terminating confidence level will have a lake that is large enough (relative to the glacier width/terminal perimeter) that it very likely is capable of affecting upstream glacier mass loss and flow dynamics. See Examples 1-4:

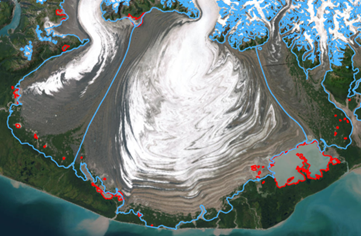

The glacier is definitely in direct contact with a lake that spans only a smaller part (clearly less than 50% but more than 10%) of the terminus, or with one or more lakes that occur at the side. Glaciers in this lake-terminating confidence level will have terminal lakes that may be relevant for upstream glacier mass loss and flow dynamics, but it is less certain than in Level 1 cases. See Examples 5-7:

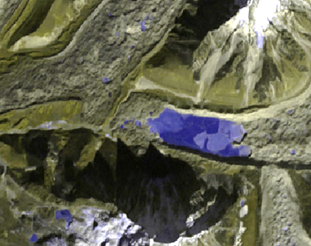

The glacier tongue is in contact with one or more small lakes (area > 0.01 km2) that collectively are in contact with <~10% of the terminal perimeter. Glaciers in this lake-terminating confidence level will have a lake(s) that likely play a relatively minor role in affecting glacier mass loss and flow dynamics. Unclear but likely cases should be included in this category. See Exampes 8 and 9:

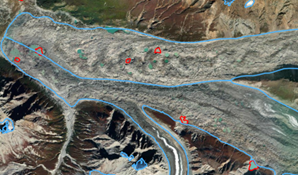

Streams cutting across termini are Level 2 in cases where the stream has a clear impact on ice melt and dynamics, otherwise they should be Level 3. See Examples 10 and 11:

A glacier that is not in direct contact with a lake. A glacier is also NOT lake-terminating, despite there being a "glacial lake" close by (i.e., the lake found in landscape formerly covered by and formed glacier ice. These kinds of lakes are included in several inventories).

A glacier with supraglacial lakes that have not amalgamated to form one lake that spans the majority of the glacier’s terminus should not be considered lake-terminating. Glaciers with proglacial water bodies smaller than 0.01 km2 should not be considered lake-terminating.

See Examples 12-15:

We rely on the best possible existing lake inventory for any region that is most closely matching the 2000 time stamp. If an inventory is lacking or too far removed in time from 2000 (>10 years away) the classification is done manually based on satellite imagery from 2000. If neither of these approaches are taken, all glaciers in that region are flagged as ‘not assigned’ terminus type (term_type = 9).

⚠️ Important note: When in doubt, put the glacier in the lower number connectivity level (i.e., higher relevance; Level 2 instead of Level 3).

⚠️ Important note: If you reviewed a glacier or region and determined that certain glaciers are definitely NOT lake-terminating (Level 0), please indicate that on your data submission (Section 3). A list that includes exclusively glaciers that are definitely not lake-terminating is helpful in its own right.

We have provided a Python script (assignRgiLakeFlag_minimal.py, included in the scripts folder) that utilizes an existing ice-marginal

lake inventory to produce a limited subset of RGI glaciers that should be manually verified for lake-terminating status.

We have compiled a list of known datasets here.

The general workflow implemented in the script is:

- create a geodatabase of terminus locations, pulling the

term_latandterm_lonfields from the RGI outlines; - buffer the terminus positions by 1 km;

- use a spatial join to join the existing lake dataset and the buffered RGI terminus positions, assigning any glacier

the join a

term_typeof 2 ("Lake-terminating").

Contributors should then manually verify the collection of lake-terminating glaciers and assign lake-terminating relevance levels, based on the examples above and the following general criteria:

- Lake-terminating level 1: >~50% of terminus is adjacent to lake; the lake(s) is definitely relevant for glacier mass loss and dynamics

- Lake-terminating level 2: ~10 - ~50% of terminus is adjacent to lake; the lake(s) is probably relevant for glacier mass loss and dynamics

- Lake-terminating level 3: <~10% of terminus is adjacent to lake, but there is some reason to think the lake is possibly dynamically relevant.

- Not lake-terminating, level 0: The glacier is not lake-terminating; its terminus is almost exclusively in contact with land (or the ocean), or has a terminal water body that is so small as to seem inconsequential for its mass loss/dynamics

- Supraglacial lakes (lakes forming entirely on top of glacier ice) should not to be considered unless they have coalesced into large water bodies than span the majority of the terminus

- Lakes smaller than 0.01 km2 should not be considered

- Glaciers with terminus cut across by a stream should be labeled as Level 2 or 3 (see guidance under “ambiguous termini” above)

- When in doubt whether the glacier is in contact with a lake or not, use level 3; if it seems more likely that the

glacier is not in contact but you cannot verify from the utilized image or any other image source (e.g. because of

clouds, snow cover, cast shadow), use the "not assigned" category (

term_type=9) - Recall that a list of definitively not lake-terminating glacier (lake level = 0) is very useful in its own right

⚠️ We strongly urge contributors to use the 0 - 3 lake-terminating level categories defined above, but will accept binary submissions ("lake-terminating"/"not lake-terminating") as well. If you are performing a binary lake-terminating classification, please consider the above-defined Levels 1 & 2 as “yes”, and please make it clear in your contribution that you did a binary classification.

In cases where no prior ice-marginal lake dataset exists, the user will have to manually inspect the termini of glaciers in your region to determine whether the glacier is lake-terminating, using the examples above the general criteria summarized in the preceding section. The RGI version 7 should be used as a starting point for glacier extents, and satellite imagery used to determine lake-terminating status should come from as close to the year 2000 as possible (within 10 years at most).

The contributors to the lake inventory should provide a csv file with the following structure (a sample template,

lake_term_data_template.csv, is provided in this repository):

rgi_id |

lake_terminating_level |

image_id |

image_date |

inventory_doi |

contributor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGI2000-v7.0-G-01-08604 | 1 | LT05_L1TP_066017_19990927_20200907_02_T1 | 1999/09/27 | https://doi.org/10.18739/A2MK6591G | Armstrong |

The fields are defined as:

rgi_id: the glacier ID from the RGI version 7lake_terminating_level: the lake terminating level, as defined in the previous sectionimage_id: The ID of the image used to verify and/or decide about the lake-terminating level. For Landsat images, please use the Product Identifier.image_date: The acquisition date of the image used to verify and/or decide about the lake-terminating level, in YYYY/MM/DD format.inventory_doi: the DOI of the lake dataset used (if exisiting), otherwise blank/NAcontributor: The name of the person(s) who checked the lake-terminating level. More than one person may be included here, but the person who checked the level must be named, and not just the supervisor or data provider.

⚠️ As stated above, we strongly urge contributors to use the 0 - 3 lake-terminating level categories defined above, but we are happy to accept binary submissions as well. If you are performing a binary lake-terminating classification, please consider the above-defined Levels 1 & 2 as "yes", and please make it clear in your contribution that you did a binary classification.

These regional tables will be merged to produce a global table of lake-terminating glaciers that will then be merged with the existing RGI tables and shapefiles.

Thank you for your time and effort! Please contact William Armstrong (armstrongwh@appstate.edu) and/or Tobias Bolch (tobias.bolch@tugraz.at) with any issues or questions.

- King, Owen, Atanu Bhattacharya, Rakesh Bhambri, and Tobias Bolch. 2019. “Glacial Lakes Exacerbate Himalayan Glacier Mass Loss.” Scientific Reports 9(1), 18145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53733-x

- Pronk, Jan Bouke, Tobias Bolch, Owen King, Bert Wouters, and Douglas I. Benn. 2021. "Contrasting Surface Velocities between Lake- and Land-Terminating Glaciers in the Himalayan Region." The Cryosphere 15(12), 5577–99. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-15-5577-2021

- Rastner, P., Bolch, T., Mölg, N., Machguth, H., Le Bris, R., Paul, F., 2012. "The first complete inventory of the local glaciers and ice caps on Greenland". The Cryosphere 6, 1483–1495. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-6-1483-2012

- Rick, Brianna, Daniel McGrath, William Armstrong, and Scott W. McCoy. 2022. "Dam type and lake location characterize ice-marginal lake area change in Alaska and NW Canada between 1984 and 2019." The Cryosphere 16(1), 297-314. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-16-297-2022

- Tsutaki, Shun, Koji Fujita, Takayuki Nuimura, Akiko Sakai, Shin Sugiyama, Jiro Komori, and Phuntsho Tshering. 2019. “Contrasting Thinning Patterns between Lake- and Land-Terminating Glaciers in the Bhutanese Himalaya.” The Cryosphere 13(10), 2733–50. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-2733-2019

- Tsutaki, Shun, Daisuke Nishimura, Takeshi Yoshizawa, and Shin Sugiyama. 2011. “Changes in Glacier Dynamics under the Influence of Proglacial Lake Formation in Rhonegletscher, Switzerland.” Annals of Glaciology 52(58), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.3189/172756411797252194

- Zhang, Guoqing, Tobias Bolch, Tandong Yao, David R. Rounce, Wenfeng Chen, Georg Veh, Owen King, Simon K. Allen, Mengmeng Wang, and Weicai Wang. 2023. “Underestimated Mass Loss from Lake-Terminating Glaciers in the Greater Himalaya.” Nature Geoscience 16(4), 333–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01150-1