These are my notes for the Structure and Implementation of Computer Programs text book.

Applicative order - evaluate the arguments and then apply.

(square (+ 5 1)) -> (square 6) -> (* 6 6) -> 36Normal order - fully expand and then reduce.

(square (+ 5 1)) -> (* (+ 5 1) (+ 5 1)) -> (* 6 6) -> 36Lisp uses applicative order evaluation.

This is why if and cond have to be special forms (see Exercise 1.6.).

(cond (<p1> <e1>)

(<p2> <e2>))

(cond (<p1> <e1>)

(else <e2>))

(if <predicate> <consequent> <alternative>)In an if expression, the consequent and alternative must be single expressions.

Recursive process is characterized by a chain of deferred operations. Carrying out this process requires the interpreter to keep track of the operations to be performed later on. Recursive process grows and then shrinks.

Iterative process does not grow and shrink. Iterative process can be characterized by a fixed number of state variables and a fixed rule describing how the state variables should be updated as the process moves from state to state. Iterative process can be executed using constant space.

Recursive procedure definition refers to itself. A recursive procedure does not have to describe a recursive process - it can describe an iterative process.

Most implementations of common languages are designed in such a way that the interpretation of any recursive procedure consumes an amount of memory that grows with the number of procedure calls, even when the process described is iterative! Therefore, in those languages (e.g. C) iterative processes can only be described using loops.

Tail-recursive property holds when iterative process described by recursive procedure is executed in constant space. With tail-recursive implementation, iteration can be expressed using ordinary procedure call mechanism.

A function f if defined by the rule that f(n) = n if n < 3 and f(n) = f(n-1) + 2f(n-2) + 3f(n-3) if n >= 3. Write a procedure that computes f by means of a recursive process. Write a procedure that computes f by means of an iterative process.

Writing a procedure that computes f by means of a recursive process is quite natural:

(define (frec n)

(if (< n 3)

n

(+

(frec (- n 1))

(* 2 (frec (- n 2)))

(* 3 (frec (- n 3)))

)

)

)What is the intuiton behind computing f by means of an iterative process? So, to compute f(n), we need f(n-1), f(n-2) and f(n-3). Looking the other way around, if we have f(n-1), f(n-2) and f(n-3) we can compute f(n). Then, we can compute f(n+1) because we have f(n), f(n-1) and f(n-2) and we no longer need f(n-3). So, we need 3 state variables and a rule to update them. Let's start by what we know and assign:

a <- f(2) = 2

b <- f(1) = 1

c <- f(0) = 0Next, we can update them according to the intuiton above:

a <- a + 2b + 3c = f(2) + 2f(1) + 3f(0) = f(3)

b <- a = f(2)

c <- b = f(1)Continuing this procedure, we can see that after n steps c = f(n). This is kind of like memoization/dynamic programming, as we only keep the values that we know we will need. Translating to Scheme:

(define (fiter-helper a b c count)

(if (= count 0)

c

(fiter-helper (+ a (* 2 b) (* 3 c)) a b (- count 1))

)

)

(define (fiter n)

(fiter-helper 2 1 0 n)

)Design a procedure that evolves an iterative exponentiation process that uses successive squaring and uses logarithmic number of steps.

Using the observation that

b^n = b^(n/2)^2 = b^2^(n/2)and suggestion to use an additional state variable a so that ab^n is constant:

(define (fast-expt-inner b n a)

(cond ((= n 0) a)

((even? n) (fast-expt-inner (* b b) (/ n 2) a))

(else (fast-expt-inner b (- n 1) (* a b)))

)

)

(define (fast-expt-iter b n) (fast-expt-inner b n 1))It is a nice suggestion to define an invariant quality that remains unchanged from state to state - it is a powerful way to think about the design of iterative algorithms.

The GCD of two integers a and b is the largest integer that divides both a and b with no remainder.

We can implement an efficient algorithm for computing GCD(a,b) based on the observation that, if r is the remainder of a divided by b, then the common divisors are exactly the same as the common divisors of b and r. Therefore, we can use the equation:

GCD(a, b) = GCD(b, r) ; where r := a mod bApplying this reduction repeatedly will finally yield a pair where the second number is 0. The GCD of any number a and 0 is a itself.

So using the above observation we can implement the algorithm:

(define (gcd a b)

(if (= b 0)

a

(gcd b (remainder a b))

)

)Using Lame's theorem it can be shown that the order of growth for the above algorithm is O(log n) where n is smaller of the two nubmers a and b.

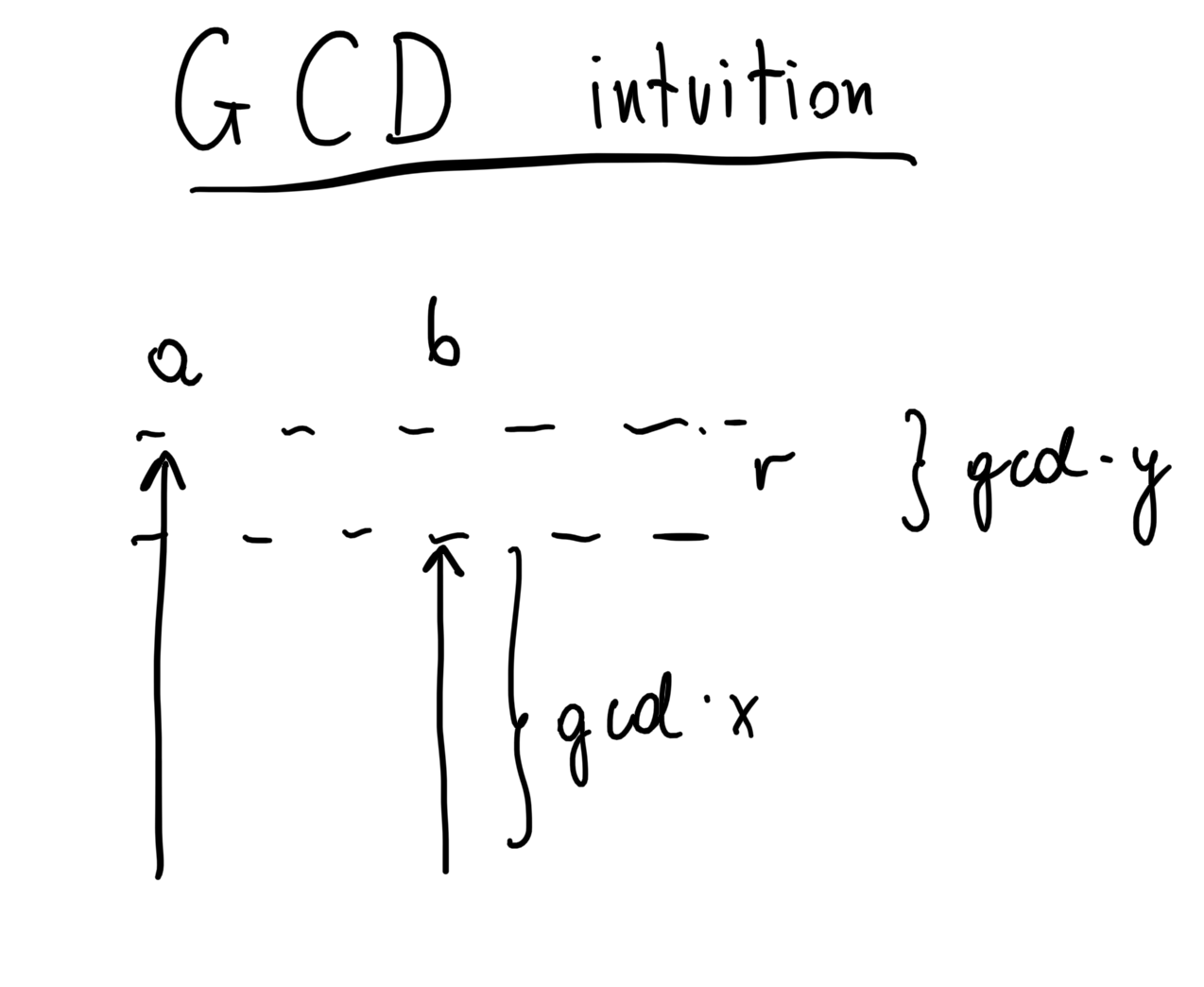

So what is the intuiton for the observation that:

GCD(a, b) = GCD(b, r)

?

Hopefully, this image provides some help:

Greatest common divisor gcd has to divide b evenly. So, we can express b as gcd times x; gcd also has to divide a evenly. We can express a as gcd times x + gcd times y; gcd times y is equal to r (x and y are arbitrary numbers). Hence, the problem comes down to finding the greatest common divisor of b and r.

Greatest common divisor gcd has to divide b evenly. So, we can express b as gcd times x; gcd also has to divide a evenly. We can express a as gcd times x + gcd times y; gcd times y is equal to r (x and y are arbitrary numbers). Hence, the problem comes down to finding the greatest common divisor of b and r.

It is easy to convince oneself, that repeating this procedure repeatedly can only make the b parameter smaller and it will eventually become 0.

How many

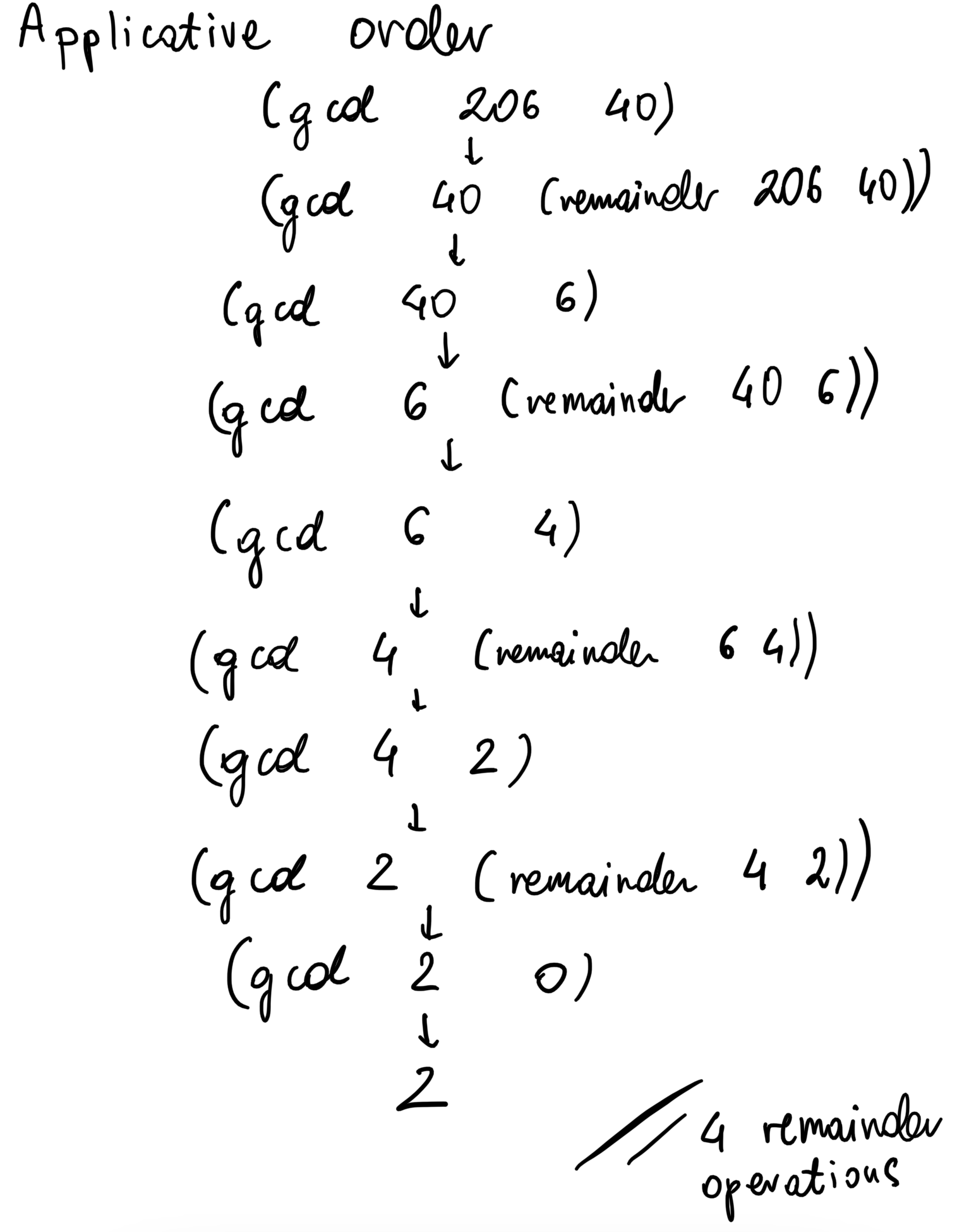

remainderoperations are actually performed in the normal-order evaluation of(gcd 206 40)? In the applicative-order evaluation?

It is easy to go through the procedure using the applicative-order evaluation and determine that it requires just 4 remainder operations:

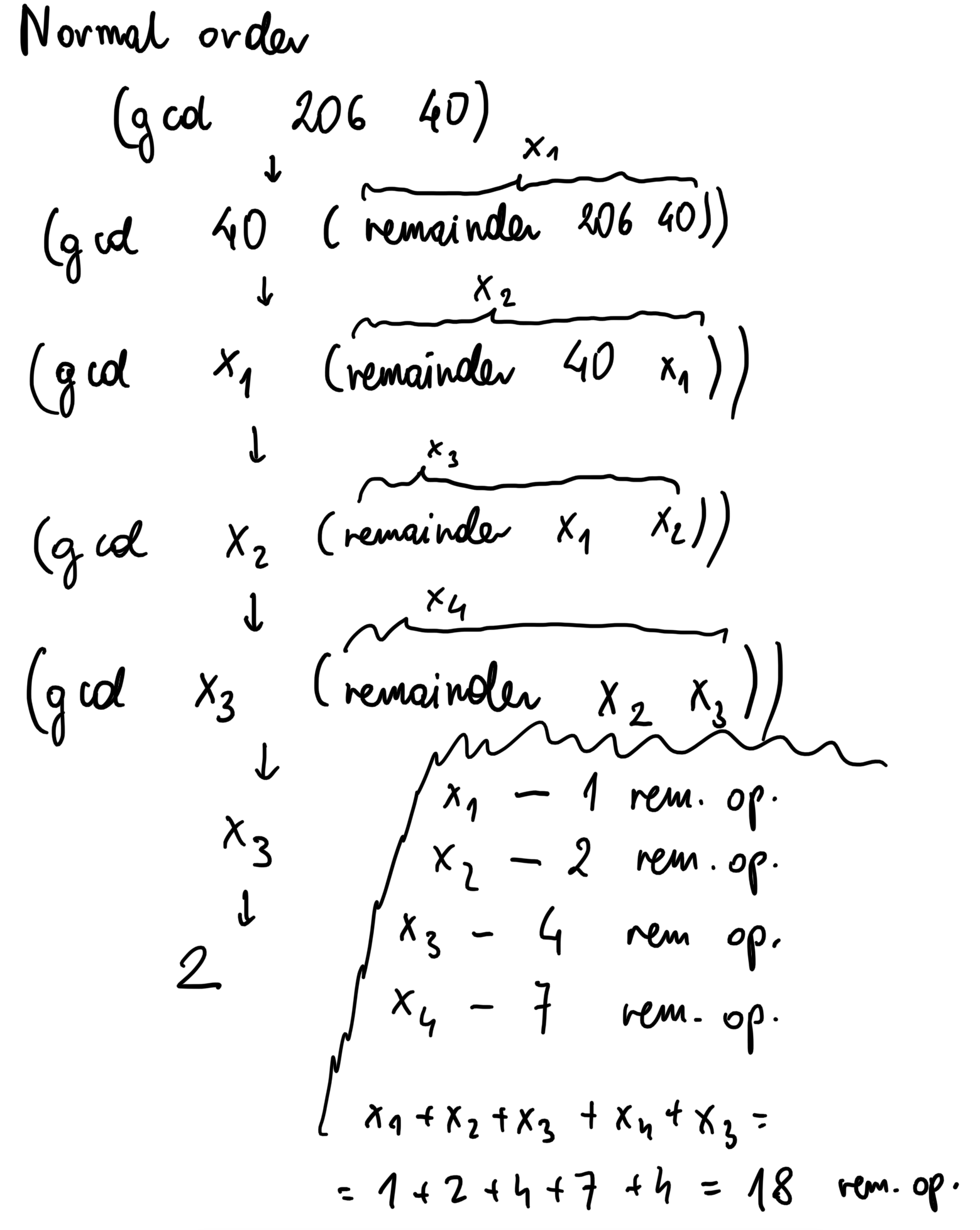

Using normal-order evaluation:

with every call, the second argument has to be evaluated as it is used in the

with every call, the second argument has to be evaluated as it is used in the if statement's predicate.

x1 requires 1 remainder operation.

x2 requires 2 remainder operations - 1 for x1 and 1 for itself.

x3 requires 4 remainder operations - 1 for x1; 2 for x2 and 1 for itself.

x4 requires 7 remainder operations - 2 for x2; 4 for x3 and 1 for itself.

Finally, x4 evaluates to 0 and expression is reduced to x3 which again requires 4 remainder operations. Summing all the required evaluations up we end up with 18 evaluations.

So, in this case applicative-order evaluation is better.

We have seen that procedures are, in effect, abstractions that describe compound operations on numbers independent of the particular numbers. For example, when we

(define (cube x) (* x x x))we are not talking about the cube of a particular number but rather about a method for obtaining the cube of any number. Of course, we could get along without ever defining this procedure, by always writing expressions such as:

(* 3 3 3)

(* x x x)and never mentioning

cubeexplicitly. This would place us at a serious disadvantage, forcing us to work always at the level of the particular operations that happen to be primitives in the language (multiplication, in this case) rather than in terms of higher-level operations. Our programs would be able to compute cubes, but our language would lack the ability to express the concept of cubing. One of the things we should demand from a powerful programming language is the ability to build abstractions by assigning names to common patterns and then to work in terms of the abstractions directly. Procedures provide this ability. This is why all but the most primitive programming languages include mechanisms for defining procedures.Yet even in numerical processing we will be severely limited in our ability to create abstractions if we are restricted to procedures whose parameters must be numbers. Often the same programming pattern will be used with a number of different procedures. To express such patterns as concepts, we will need to construct procedures that can accept procedures as arguments or return procedures as values. Procedures that manipulate procedures are called higher-order procedures.

(lambda (<formal-parameters>) <body>)

let is syntactic sugar for application of lambda

Example:

f(x,y) = x(1+xy)^2 + y(1-y) + (1+xy)(1-y)

could be expressed as:

f(x, y) = xa^2 + yb + ab; where a = 1 + xy and b = 1 - y

Translating to Scheme we can bind those local variables a and b using another inner procedure:

(define (f x y)

(define (f-helper a b)

(+ (* x (square a))

(* y b)

(* a b)

)

)

(f-helper (+ 1 (* x y)) (- 1 y))

)This can also be expressed using lambda:

(define (f x y)

(

(lambda (a b)

(+ (* x (square a))

(* y b)

(* a b)

)

)

)(

(+ 1 (* x y))

(- 1 y)

)

)There is a special form called let that makes it more convenient:

(define (f x y)

(let (

(a (+ 1 (* x y)))

(b (- 1 y))

)

( + (* x (square a ))

(* y b)

(* a b)

)

)

)Its general form is:

(let (

(<var1> <exp1>)

(<var2> <exp2>)

)

<body>

)It is preferred to use let to define local variables instead of define. It is better to use define for internal procedures only.

Data abstraction is a methodology that enables us to isolate how a compound data object is used from the details of how it is constructed from more primitive data objects.

The basic idea of data abstraction is to structure the programs that are to use compound data objects so that they operate on abstract data.

This methodology enables us to make use of abstraction barriers. This is done by building programs that make use only of the public methods provided by the abstraction from the "lower layer". This makes programs easier to maintain and modify. There is no need to worry about the details of how the underlying methods are implemented. In addition, underlying methods implementation can be changed and as long as the signatures and behaviour of public methods remain unchanged, previously written programs should work just fine.

What is meant by data? In general, we can think of data as defined by some collection of selectors and constructors, together with specified conditions that these procedures must fulfill in order to be a valid representation.

(define (cons x y)

(lambda (m) (m x y))

)

(define (car z)

(z (lambda (p q) p))

)

(define (cdr z)

(z (lambda (p q) q))

)A hand-wavy description of this exercise: cons takes in two arguments and returns a function that takes in another function as a parameter and applies it to the two arguments passed to cons. So, to get the first argument, car calls the function returned by cons with a function that just returns the first parameter. Cdr's implementation is analogous.

In general, an operation for combining data objects satisfies the closure property if the results of combining things with that operation can themselves be combined using the same operation. Closure is the key to power in any means of combination because it permits us to create hierarchical structures -- structures made up of parts, which themselves are made up of parts, and so on.

The use of the word closure here comes from abstract algebra, where a set of elements is said to be closed under an operation if applying the operation to elements in the set produces an element that is again an element of the set. The Lisp community also (unfortunately) uses the word closure to describe a totally unrelated concept: A closure is an implementation technique for representing procedures with free variables. We do not use the word closure in this second sense in this book.

A set can be represented as a list of elements. A set of all subsets can be represented as a list of lists. A set of all subsets can be computed by appending the head of the list to all of the subsets of the tail of the list. Then, the set of all subsets is a union of sets with head appended and the subsets of tail. Translating to Scheme:

(define (subsets s)

(if (null? s)

(list '())

(let ((rest (subsets (cdr s))))

(append rest (map (lambda (subset) (cons (car s) subset)) rest))

)

)

)Operations on sequences such as accumulate, filter, map and enumerate describe very common patterns that are useful for many different applications. By using those common methods our programs are more modular. It is also a good strategy to manage complexity. Moreover, expressing our programs using those common interfaces makes it easier to reason about them and also makes it easier for other people to understand.

Here is a plan for generating the permutations of S: For each item x in S, recursively generate the sequence of permutations of S - x and adjoin x to the front of each one. This yields, for each x in S, the sequence of permutations of S that begin with x. Combining these sequences for all x gives all the permutations of S.

(define (permutations s)

(if (null? s)

(list '())

(flatmap (lambda (x)

(map (lambda (p) (cons x p)) (permutations (remove x s)))

)

s

)

)

)We have also obtained a glimpse of another crucial idea about languages and program design. This is the approach of stratified design, the notion that a complex system should be structured as a sequence of levels that are described using a sequence of languages. Each level is constructed by combining parts that are regarded as primitive at that level, and the parts constructed at each level are used as primitives at the next level. The language used at each level of a stratified design has primitives, means of combination, and means of abstraction appropriate to that level of detail.

Stratified design pervades the engineering of complex systems. For example, in computer engineering, resistors and transistors are combined (and described using a language of analog circuits) to produce parts such as and-gates and or-gates, which form the primitives of a language for digital-circuit design. These parts are combined to build processors, bus structures, and memory systems, which are in turn combined to form computers, using languages appropriate to computer architecture. Computers are combined to form distributed systems, using languages appropriate for describing network interconnections, and so on.

Stratified design helps make programs robust, that is, it makes it likely that small changes in a specification will require correspondingly small changes in the program. [...] In general, each level of a stratified design provides a different vocabulary for expressing the characteristics of the system, and a different kind of ability to change it.

(define (list->tree elements)

(car (partial-tree elements (length elements))))

(define (partial-tree elts n)

(if (= n 0)

(cons '() elts)

(let ((left-size (quotient (- n 1) 2)))

(let ((left-result (partial-tree elts left-size)))

(let ((left-tree (car left-result))

(non-left-elts (cdr left-result))

(right-size (- n (+ left-size 1))))

(let ((this-entry (car non-left-elts))

(right-result (partial-tree (cdr non-left-elts)

right-size)))

(let ((right-tree (car right-result))

(remaining-elts (cdr right-result)))

(cons (make-tree this-entry left-tree right-tree)

remaining-elts))))))))Procedure list->tree converts an ordered list into a binary tree, while (partial-tree elts n) produces a balanced tree containing first n elements of the ordered list. It takes in an integer n and a list of at least n element elts and returns a pair whose car is the constructed tree and whose cdr is the list of element that was not included in the tree.

This procedure works as follows:

Firstly, if n equals 0, then return a pair consisting of an empty tree and a list of elements that were not included in the tree.

Then, determine the size of the left subtree. It is equal to (quotient (- n 1) 2). We subtract 1 from n to not count the entry value and then we divide the rest by 2 to form balanced left and right subtrees. So the size of the left subtree contains roughly half of the elements that are to be included in the tree.

Next, the left tree is constructed recursively by passing the elts and left-size to the partial-tree procedure.

Then, we can define left-tree using (car left-result). The elements that were not included in the left subtree are non-left-elts. The size of the right subtree has to be (- n (+ left-size 1)) - we subtract the size of the left subtree and the entry node. We use the first element of the non-left-elts as entry value and then construct the right subtree recursively using the partial-tree procedure.

Finally, we can just construct the tree using the left subtree, entry value and right subtree and also return the elements that were not included. By initially calling the partial-tree procedure with n equal to the length of elts we guarantee that no elements will be left out from the final tree. Initially, elts have to be ordered so that the tree is a binary tree (elements in the left subtree are smaller or equal to the entry node and elements in the right subtree are larger or equal to the entry node).

The order of growth is O(n). Every time partial-tree is called it calls itself twice, but with n halved. Intuitively, every node has to be visited once.

]=> (list->tree (list 1 3 5 7 9 11))

; 5

; / \

; / \

; / \

; 1 9

; \ / \

; 3 7 11The general strategy of checking the type of a datum and calling an appropriate procedure is called dispatching on type. Weaknesses of dispatching o na type:

- generic interface procedures must know about all the different representations (types)

- no two procedures in the entire system can have the same name

This technique is not additive - each time a new representation (type) is installed, the person implementing this representation has to modify procedures for generic selectors and the people interfacing the individual representation must modify their code to avoid name conflicts.

Data-directed programming is a technique of designing programs to work with a table of operations -- rows are operations, columns are types and entries are implementations. (note: related to the expression problem https://craftinginterpreters.com/representing-code.html#the-expression-problem and the visitor pattern)

An alternative strategy to data-directed programming. In this approach the data object is an entity that receives the requested operation name as a "message". Example:

(define (make-from-real-imag x y)

(define (dispatch op)

(cond ((eq? op 'real-part) x)

((eq? op 'imag-part) y)

((eq? op 'magnitude)

(sqrt (+ (square x) (square y))))

((eq? op 'angle) (atan y x))

(else

(error "Unknown op -- MAKE-FROM-REAL-IMAG" op))))

dispatch)We ordinarily view the world as populated by independent objects, each of which has a state that changes over time. An object is said to ``have state'' if its behavior is influenced by its history. We can characterize an object's state by one or more state variables, which among them maintain enough information about history to determine the object's current behavior.

In a system composed of many objects, the objects are rarely completely independent. Each may influence the states of others through interactions, which serve to couple the state variables of one object to those of other objects. Indeed, the view that a system is composed of separate objects is most useful when the state variables of the system can be grouped into closely coupled subsystems that are only loosely coupled to other subsystems.

This view of a system can be a powerful framework for organizing computational models of the system. For such a model to be modular, it should be decomposed into computational objects that model the actual objects in the system. Each computational object must have its own local state variables describing the actual object's state. Since the states of objects in the system being modeled change over time, the state variables of the corresponding computational objects must also change. If we choose to model the flow of time in the system by the elapsed time in the computer, then we must have a way to construct computational objects whose behaviors change as our programs run. In particular, if we wish to model state variables by ordinary symbolic names in the programming language, then the language must provide an assignment operator to enable us to change the value associated with a name.

By introducing assignment and the technique of hiding state in local variables, we are able to structure systems in a modular fashion. However, we loose referartional transparency and the substition model can no longer be used to reason about our programs. Now a variable somehow refers to a place where a value can be stored, and the value stored at this place can change. Instead, a notion of environments has to be introduced.

In general, programming with assignment forces us to carefully consider the relative orders of the assignments to make sure that each statement is using the correct version of the variables that have been changed. This issue simply does not arise in functional programs. The complexity of imperative programs becomes even worse if we consider applications in which several processes execute concurrently.

The central issue lurking beneath the complexity of state, sameness, and change is that by introducing assignment we are forced to admit time into our computational models. Before we introduced assignment, all our programs were timeless, in the sense that any expression that has a value always has the same value. After introducing assignment, successive evaluations of the same expression can yield different values. The result of evaluating an expression depends not only on the expression itself, but also on whether the evaluation occurs before or after these moments. Building models in terms of computational objects with local state forces us to confront time as an essential concept in programming.

The practice of writing programs as if they were to be executed concurrently forces the programmer to avoid inessential timing constraints and thus makes programs more modular.

In addition to making programs more modular, concurrent computation can provide a speed advantage over sequential computation. Sequential computers execute only one operation at a time, so the amount of time it takes to perform a task is proportional to the total number of operations performed. However, if it is possible to decompose a problem into pieces that are relatively independent and need to communicate only rarely, it may be possible to allocate pieces to separate computing processors, producing a speed advantage proportional to the number of processors available.

The problem is that several processes may share a state variable and try to manipulate it at the same time.

Streams can be used to implement well-defined mathematical functions whose behaviour doesn't change, but from user's perspecvtive the system appears to have changing state. The former is extremely attractive for dealing with concurrent systems.

With streams we can achieve the best of both worlds: We can formulate programs elegantly as sequence manipulations, while attaining the efficiency of incremental computation.

On the other hand, if we look closely, we can see time-related problems creeping into functional models as well. One particularly troublesome area arises when we wish to design interactive systems, especially ones that model interactions between independent entities. (e.g. how to 'merge' two incoming streams?)

Metaliguistic Abstraction revolves around establishing new languages. An evaluator (or interpreter) for a programming language is a procedure that, when applied to an expression of the language, performs the actions to evaluate that expression. The evaluator determines the meaning of expressions in a programming language. The evaluator is just another program.

An evaluator reduces the expressions in the environments to procedures that have to be applied with specific arguments. Those in turn, are reduced to new expressions in new environments. The cycle continues until we get to primitive procedures that can be applied directly, or symbols, which values can be just looked up in the environment.

An evaluator that is written in the same language that it evaluates is said to be metacircular.

A macro is a mechanism for adding user-defined transformations that allow the user to add new derived expressions and specify their implementation as syntactic transformations without modifying the evaluator.

A special form is a primitive function specially marked so that its arguments are not all evaluated. Most special forms define control structures or perform variable bindings—things which functions cannot do.

Parsing is matching the input against some grammatical structure.