In this tutorial we will cover how to access the public, machine readable site DBPedia, which contains information scraped from Wikipedia. This data is stored in RDF (or RDF like) format, and can be queried via a language called SPARQL. We will cover all 3 of these technologies to varying extents.

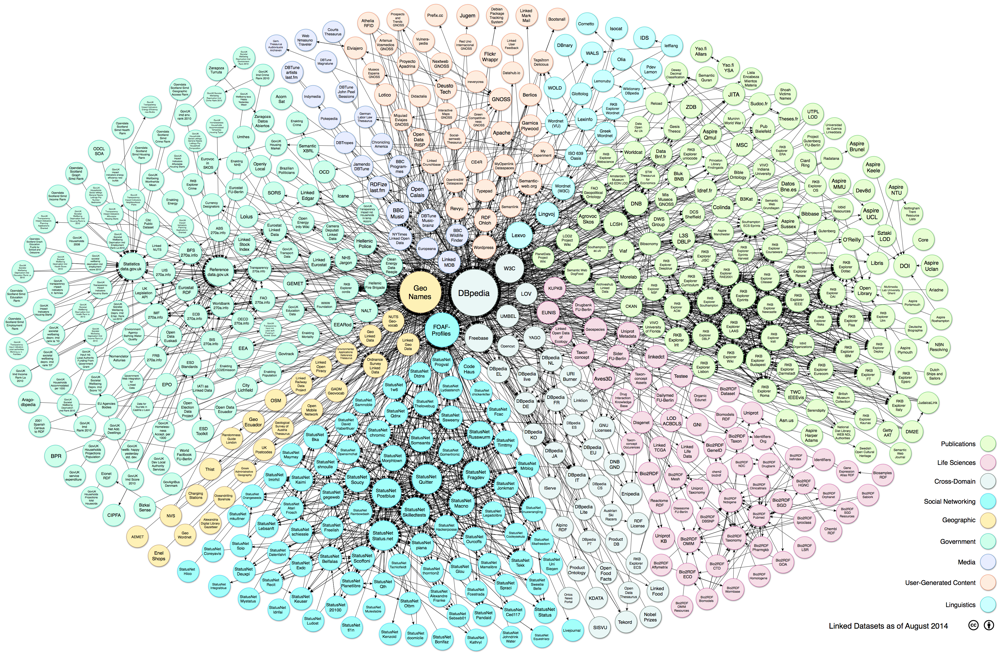

DBPedia is a crowd-sourced effort that aims to extract structured data from a variety of different Wikimedia projects. The data is structured as an open knowledge graph (OKG), so it's available to everyone on the web. This critical structured data is published strictly within some "Linked Open Data" guidelines. This Linked Open Data Cloud has grown to become a huge collection of structed data as RDF Predicate/Property Graphs.

This data from the Wikimedia projects is exposed in a form that many tools, including natural=-language processing, machine learning, and artificial intellignece, are actually compatible with. Basically, DBPedia enabled the Linked Open Data Cloud to become the huge reference database. Since DBPedia is served as linked data, it can be interacted with in a variety of different ways:

- standard web browsers

- automated crawlers

- complex queries with SQL-like query languages (e.g. SPARQL)

SPARQL is a query language that works on data stored in the Resource Description Framework (RDF) format. RDF data can be thought of as a loose interpretation of key-value data, consisting of subject-predicate-object triplets. These triplets are very similar to MongoDBs "document-key-value" triplets. To simplify in terms of relational databases, the subject is like an entity, the predicate it's columns, and the objects are the actual values for those columns. Unlike relational databases, RDF can have multiple entries per predicate, and even the object data type is heterogenous, though usually implied by the predicate.

What really sets SPARQL apart though, is the ability to use web identifiers for the entities that are being described. This allows for the RDF data to be merged from multiple databases without any sort of intermediate step of mapping terms between them that a relational would require. This means that as long as your data follows the RDF format, you can set upa SPARQL endpoint that basically allows you to be a service provider for your data, and to use data from other endpoints to create a mashup that can be of great use.

To understand SPARQL, it is important to also understand how an RDF document is structured. RDF is based around the idea of storing statements, which include 3 required parts: a subject, a predicate, and an object. For example, in the statement

The instructor of CSE 5914 is Stephen Boxwell.

- The subject of the statement is CSE 5914

- The predicate is instructor

- The object is Stephen Boxwell

With this in mind, we can consider how this information might be structured within the general framework of XML.

RDF files begin with the standard XML version tag

<?xml version="1.0"?>

after which you can optionally define URI's for the various elements to be defined. An important one is to define the actual structure of RDF by including

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">

at a minimum. You can add additional lines for each of the resources you wish to define. To define a "dog" resource, you could do the following:

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:dog="http://www.dog.fake/dog#">

Next step is to define the actual resources. Following the dog example, a theoretical resource may look like

<rdf:Description

rdf:about="http:www.dog.fake/dogabout">

<dog:name>Spike</dog:name>

<dog:breed>Beagle</dog:breed>

<dog:bark>Woof!</dog:bark>

</rdf:Description>

Notice that the tags follow the subject, predicate, object paradigm. For the first line for instance, the subject of the statement is "dog", the predicate is "name", and the object is "Spike".

This tutorial focuses on DBPedia, which as previously stated is a massive collection of RDF or RDF like documents that can be queried with SPARQL. So while we will not be writing anymore RDF code, it is still vital to understand the basics of the framework in order to make use of SPARQL and DBPedia.

Note: To follow along with the non DBPedia examples below, you can install Apache Jena and run the following command using the example files provided (be sure to edit query.rq first):

arq --data test.rdf --query query.rq

SPARQL is fairly similar to standard SQL, although it generally requires more information in order to successfully execute queries due to the nature of RDF versus a DBMS. Queries follow the very general structure of

SELECT ?object WHERE { $subject $predicate $object }

At least one of the values within the WHERE is unknown and denoted with a ? as a prefix. This

constitutes what you are querying for. So, to query for the resource of any dog that

is a Beagle we would do

SELECT ?dog WHERE { ?dog <http://www.dog.fake/dog#breed> "Beagle" }

Note that this will return the about URI for the dog resource. Normally this is

not what we want; we want an actual object that is associated with the resource.

To do this, we need to add additional queries leveraging the returned dog object.

Multiple statements can be separated with a .. For this example:

SELECT ?name WHERE { ?dog <http://www.dog.fake/dog#breed> "Beagle" .

?dog <http://www.dog.fake/dog#name> ?name

}

Will return "Spike".

There is another concept that comes up when working with SPARQL, which are prefixes. Prefixes are syntactic sugar which can shorted queries. They are defined by putting something like

PREFIX dog: <http://www.dog.fake/dog#>

at the beginning of your query. The above query would become

PREFIX dog: <http://www.dog.fake/dog#>

SELECT ?name WHERE { ?dog dog:breed "Beagle" .

?dog dog:name ?name

}

This is important to know as DBPedia has many built in prefixes that it assumes you will be using including

PREFIX owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#>

PREFIX xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#>

PREFIX rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#>

PREFIX rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#>

PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/>

PREFIX dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/>

PREFIX : <http://dbpedia.org/resource/>

PREFIX dbpedia2: <http://dbpedia.org/property/>

PREFIX dbpedia: <http://dbpedia.org/>

PREFIX skos: <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#>

With the basic groundwork for SPARQL laid, we can now talk about how to use it to search DBPedia. Since it is a wrapper for Wikipedia, all the subject tags found on Wikipedia pages will have statements associated with them. To look at the tags for the Dog entry on Wikipedia, you can go to the following page. This URL scheme should work for any existing Wikipedia entry, although not everything is a page so extensions will vary slightly. The following queries can be run on the snorql website for simplicity.

Suppose we want to get the genus and species of the dog. In this case, since we

already know the URI for the "Dog" resource, we can skip querying for that and

just ask for our desired objects. In the query below, dbr refers to resources

(i.e. top level pages) and dbp refers to basic information on the page. Refer

back to the link above for more examples of dbr values.

SELECT ?genus ?species WHERE { dbr:Dog dbp:genus ?genus .

dbr:Dog dbp:species ?species

}

There are two listings for species (one short and one long), so we get a cross product of that with the genus. If we just wanted the first result no matter what, we could limit the results. To do this change the query to

SELECT ?genus ?species WHERE { dbr:Dog dbp:genus ?genus .

dbr:Dog dbp:species ?species

} LIMIT 1

While useful, this query is not terribly interesting. It is something that could be done without the overhead of DBPedia and SPARQL with simple web scraping. SPARQL can of course be used for much more complicated queries through additional metadata and relations it has access to. The ontology capabilities are particularly useful, and can help with queries the involve classification and instances of various resources. Keeping with the dog theme, if we want to find examples of things that are dogs we could run

PREFIX d: <http://dbpedia.org/ontology/>

SELECT ?examples

WHERE {

?examples d:species :Dog .

}

which returns a variety of real and fictional dogs including Brian Griffin and McGruff. Going further with this, we can get a join of (fictional) dogs with their respective creators by doing

PREFIX d: <http://dbpedia.org/ontology/>

SELECT ?examples ?name

WHERE {

?examples d:species :Dog .

?examples d:creator ?name .

}

This will only return dogs that have a creator associated with them, so if all

the dogs returned in ?examples were real dogs with no creators this query

would return nothing.

First things first. You'll need to install or make your own SPARQL Wrapper. We chose to use a python wrapper

With pip

$ pip install sparqlwrapper

All of this code can be found in "example.py" in this repository. First you'll need to import the wrapper and make the object. We're using DBPedia's endpoint

from SPARQLWrapper import SPARQLWrapper, JSON

import pprint

sparql = SPARQLWrapper("http://dbpedia.org/sparql")

Next we have to set a query

sparql.setQuery(

"""

SELECT ?genus ?species WHERE { dbr:Dog dbp:genus ?genus .

dbr:Dog dbp:species ?species

}

"""

)

Then we run the query and format it as JSON for easy mode parsing!

sparql.setReturnFormat(JSON)

results = sparql.query().convert()

which when pretty printed becomes

{'head': {'link': [], 'vars': ['genus', 'species']},

'results': {'distinct': False,

'ordered': True,

'bindings': [{'genus': {'type': 'typed-literal',

'datatype': 'http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#langString',

'value': 'Canis'},

'species': {'type': 'typed-literal',

'datatype': 'http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#langString',

'value': 'Canis lupus familiaris'}},

{'genus': {'type': 'typed-literal',

'datatype': 'http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#langString',

'value': 'Canis'},

'species': {'type': 'typed-literal',

'datatype': 'http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#langString',

'value': 'lupus'}}]}}

- DBPedia

- Why is DBPedia Important

- SPARQL

- Cambridge Semantics

- SPARQL Python Library

- XML RDF

- Learning SPARQL by Bob DuCharme (ISBN: 9781449371432)

- Sander Henning

- Frank Meszaros

- Joel Pepper

- Zach Ponath

- Shashank Rajkumar

- Skyler Reimer

- Ethan Smith