ScalaTags is a small, fast XML/HTML construction library for Scala that takes fragments in plain Scala code that look like this:

html(

head(

script(src:="..."),

script(

"alert('Hello World')"

)

),

body(

div(

h1(id:="title", "This is a title"),

p("This is a big paragraph of text")

)

)

)And turns them into HTML like this:

<html>

<head>

<script src="..." />

<script>alert('Hello World')</script>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<h1 id="title">This is a title</h1>

<p>This is a big paragraph of text</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>ScalaTags is hosted on Maven Central; to get started, simply add the following to your build.sbt:

libraryDependencies += "com.scalatags" % "scalatags_2.10" % "0.2.2"And you're good to go! Open up a sbt console and you can start working through the Examples, which should just work when copied and pasted into the console, browse the Scaladoc, or ask a question on the mailing list

To use Scalatags with a ScalaJS project, add the following to the built.sbt of your ScalaJS project:

libraryDependencies += "com.scalatags" % "scalatags_2.10" % "0.2.2-JS"And you should be good to go generating HTML fragments in the browser! Scalatags has no dependencies, and so all the examples should work right off the bat whether run in Chrome, Firefox or Rhino. Scalatags 2.2-JS is currently only compatibly with ScalaJS 2.1.

The core functionality of Scalatags is less than 500 lines of code, and yet it provides all the functionality of large frameworks like Python's Jinja2 or C#'s Razor, and out-performs the competition by a large margin. It does this by leveraging the functionality of the Scala language to do almost everything, meaning you don't need to learn a second template pseudo-language just to stitch your HTML fragments together

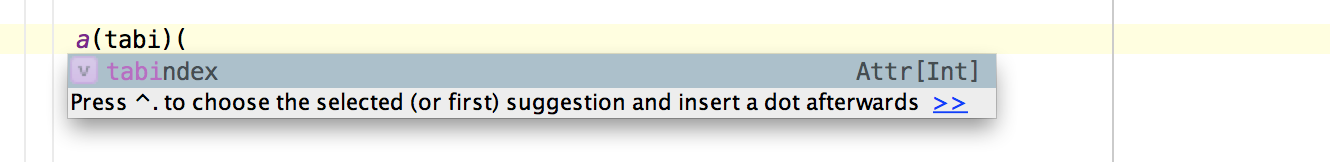

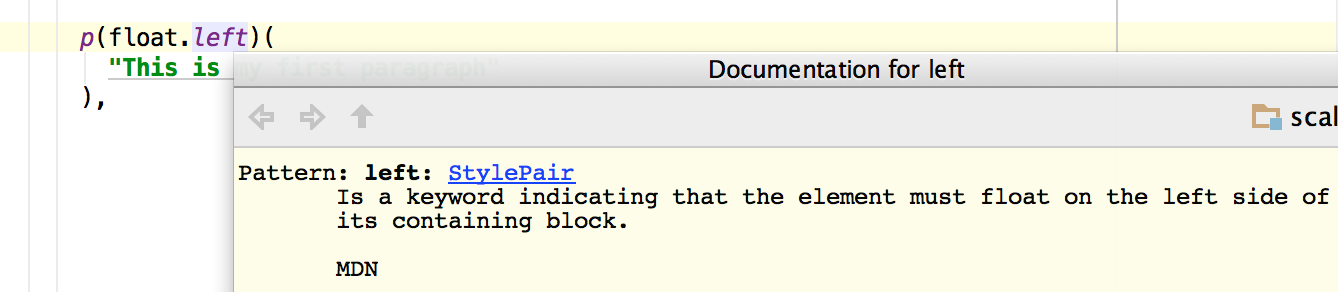

Since ScalaTags is pure Scala. This means that any editor which understands Scala will understand ScalaTags. Not only do you get syntax highlighting, you also get code completion:

and Error Highlighting:

and in-editor documentation:

And all the other good things (jump to definition, extract method, etc.) you're used to in a statically typed language. No more digging around in templates which mess up the highlighting of your HTML editor, or waiting months for the correct plugin to materialize.

Take a look at the prior work section for a more detailed analysis of Scalatags in comparison to other popular libraries.

This is a bunch of simple examples to get you started using ScalaTags. These examples are all in the unit tests.

import scalatags.all._

val frag = html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p("This is my first paragraph"),

p("This is my second paragraph")

)

)

)The core of Scalatags is a way to generate (X)HTML fragments using plain Scala. This is done by values such as head, script, and so on, which are automatically imported into your program when you import scalatags.all._. See below if you want more fine-grain control over what's imported.

This example code creates a Scalatags fragment. We could do many things with a fragment: store it, return it, it's just a normal Scala value. Eventually, though, you will want to convert it into HTML. To do this, simply use:

frag.toStringWhich will give you a String containing the HTML representation:

<html><head><script>some script</script></head><body><h1>This is my title</h1><div><p>This is my first paragraph</p><p>This is my second paragraph</p></div></body></html>This representation omits unnecesary whitespace. To improve readability we could pretty print it using some XML processing:

val prettier = new scala.xml.PrettyPrinter(80, 4)

println(prettier.format(scala.xml.XML.loadString(frag.toString)))executing that prints out:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<p>This is my first paragraph</p>

<p>This is my second paragraph</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>The following examples will simply show the initial Scalatag fragment and the final prettyprinted HTML, skipping the intermediate steps.

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p(onclick:="... do some js")(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(href:="www.google.com")(

p("Goooogle")

)

)

)

)In Scalatags, each attribute has an associated value which can be used to set it. This example shows you set the onclick and href attributes with the := operator. These are all instances of the Attr class.

The common HTML attributes all have static values to use in your fragments, and the list can be seen here. This keeps things concise and statically checked. However, inevitably you'll want to set some attribute which isn't in the initial list defined by Scalatags. This can be done with the .attr method that Scalatags adds to Strings:

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p("onclick".attr:="... do some js")(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a("href".attr:="www.google.com")(

p("Goooogle")

)

)

)

)If you wish to, you can also take the result of the .attr call and assign it to a variable for you to use later in an identical way. Both of these print the same thing:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<p onclick="... do some js">

This is my first paragraph

</p>

<a href="www.google.com">

<p>Goooogle</p>

</a>

</div>

</body>

</html>val contentpara = "contentpara".cls

val first = "first".cls

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1(backgroundColor:="blue", color:="red")("This is my title"),

div(backgroundColor:="blue", color:="red")(

p(contentpara, first)(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(opacity:=0.9)(

p("contentpara".cls)("Goooogle")

)

)

)

)In HTML, the class and style attributes are often thought of not as normal attributes (which contain strings), but as lists of strings (for class) and lists of key-value pairs (for style). Furthermore, there is a large but finite number of styles, and not any arbitrary string can be a style. The above example shows how CSS classes and inline-styles are typically set.

Note that in this case, backgroundColor, color, contentpara, first and opacity are all statically typed identifiers. The two CSS classes contentpara and first (Instances of Cls) are defined just before, while backgroundColor, color and opacity (Instances of Style) are defined by Scalatags.

Of course, class and style are in the end just attributes, so you can treat them as such and bind them directly without any fuss:

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1(style:="background-color: blue; color: red;")("This is my title"),

div(style:="background-color: blue; color: red;")(

p(`class`:="contentpara first")(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(style:="opacity: 0.9;")(

p("contentpara".cls)("Goooogle")

)

)

)

)Both of these print the same thing:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1 style="background-color: blue; color: red;">This is my title</h1>

<div style="background-color: blue; color: red;">

<p class="contentpara first">This is my first paragraph</p>

<a style="opacity: 0.9;">

<p class="contentpara">Goooogle</p>

</a>

</div>

</body>

</html>A list of the attributes and styles provided by ScalaTags can be found in Attrs and Styles. This of course won't include any which you define yourself.

div(

p(float.left)(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(tabindex:=10)(

p("Goooogle")

),

input(disabled:=true)

)Not all attributes and styles take strings; some, like float, have an enumeration of valid values, and can be referenced by float.left, float.right, etc.. Others, like tabindex or disabled, take Ints and Booleans respectively. These are used directly as shown in the example above. Attempts to pass in strings to float:=, tabindex:= or disabled:= result in compile errors.

Even for styles or attributes which take values other than strings (e.g. tabindex) the := operator can still be used to force assignment:

div(

p(float:="left")(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(tabindex:="10")(

p("Goooogle")

),

input(disabled:="true")

)Both of these print the same thing:

<div>

<p style="float: left;">This is my first paragraph</p>

<a tabindex="10">

<p>Goooogle</p>

</a>

<input disabled="true" />

</div>import scalatags.{Attributes => a, Styles => s, _}

import scalatags.Tags._

div(

p(s.color:="red")("Red Text"),

img(a.href:="www.imgur.com/picture.jpg")

)Apart from using import scalatags.all._, it is possible to perform the imports manually, renaming whatever you feel like renaming. The example above provides an example which imports all HTML tags, but imports Attrs and Styles aliased rather than dumping their contents into your global namespace. This helps avoid polluting your namespace with lots of common names (e.g. value, id, etc.) that you may not use.

The main objects which you can import things from are:

- Tags: common HTML tags

- Tags2: less common HTML tags

- Attrs: common HTML attributes

- Styles: common CSS styles

- Styles2: less common CSS styles

- Svg: SVG tags

- SvgStyles: CSS styles only associated with SVG elements

- DataTypes: case classes representing CSS length, colors, etc.

- DataConverters: convenient extensions (e.g.

10.px) to create the CSS datatypes

You can pick and choose exactly which bits you want to import, or you can use one of the provided aggregates:

- all: this imports the contents of Tags, Attrs, Styles and DataConverters

- short: this imports the contents of Tags and DataConverters, but aliases Attrs and Styles as

*

Thus, you can choose exactly what you want to import, and how:

import scalatags.{Attributes => attr, Styles => css, _}

import scalatags.Tags._

div(

p(css.color:="red")("Red Text"),

img(attr.href:="www.imgur.com/picture.jpg")

)Or you can rely on a aggregator like all (which the rest of the examples use) or short. short imports Attrs and Styles as *, making them quick to access without cluttering the global namespace:

import scalatags.short._

div(

p(*.color:="red")("Red Text"),

img(*.href:="www.imgur.com/picture.jpg")

)If you wish to put together your own collection of imports, all the objects described above (Tags, Attrs, etc.) are also available as traits, so you can put together your own:

object custom extends Tags{

val attr = new Attributes {}

val css = new Styles {}

}

import custom._

div(

p(css.color:="red")("Red Text"),

img(attr.href:="www.imgur.com/picture.jpg")

)In this case, you can define custom top-level somewhere, and simply have everyone else use import custom._ to get exactly what you want. All three of of these examples print

<div>

<p style="color: red;">Red Text</p>

<img href="www.imgur.com/picture.jpg" />

</div>This custom import object also provides you a place to define your own custom tags that will be imported throughout your project e.g. a js(s: String) tag as shorthand for script(src:=s). You can even override the default definitions, e.g. making script be a shorthand for script(type:="javascript") so that you can never forget to use your own custom version.

The lesser used tags or styles are generally not imported wholesale by default, but you can always import the ones you need:

import Styles2.pageBreakBefore

import Tags2.address

import SvgTags.svg

import SvgStyles.stroke

div(

p(pageBreakBefore.always, "a long paragraph which should not be broken"),

address("500 Memorial Drive, Cambridge MA"),

svg(stroke:="blue")

)This prints:

<div>

<p style="page-break-before: always;">

a long paragraph which should not be broken

</p>

<address>500 Memorial Drive, Cambridge MA</address>

<svg style="stroke: blue;" />

</div>val title = "title"

val numVisitors = 1023

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my ", title),

div(

p("This is my first paragraph"),

p("you are the ", numVisitors.toString, "th visitor!")

)

)

)Variables can be inserted into the templates as Strings, simply by adding them to an element's children. This prints

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<p>This is my first paragraph</p>

<p>you are the 1023th visitor!</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>val numVisitors = 1023

val posts = Seq(

("alice", "i like pie"),

("bob", "pie is evil i hate you"),

("charlie", "i like pie and pie is evil, i hat myself")

)

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div("posts"),

for ((name, text) <- posts) yield div(

h2("Post by ", name),

p(text)

),

if(numVisitors > 100) p("No more posts!")

else p("Please post below...")

)

)Like most other XML templating languages, ScalaTags contains control flow statements like if and for. Unlike other templating languages which have their own crufty little programming language embedded inside them for control flow, you probably already know how to use ScalaTags' control flow syntax. They're just Scala after all.

This prints out:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>posts</div>

<div>

<h2>Post by alice</h2>

<p>i like pie</p>

</div>

<div>

<h2>Post by bob</h2>

<p>pie is evil i hate you</p>

</div>

<div>

<h2>Post by charlie</h2>

<p>i like pie and pie is evil, i hat myself</p>

</div>

<p>No more posts!</p>

</body>

</html>def imgBox(source: String, text: String) = div(

img(src:=source),

div(

p(text)

)

)

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

imgBox("www.mysite.com/imageOne.png", "This is the first image displayed on the site"),

div(`class`:="content")(

p("blah blah blah i am text"),

imgBox("www.mysite.com/imageTwo.png", "This image is very interesting")

)

)

)Many other templating systems define incredibly roundabout ways of creating re-usable parts of the template. In ScalaTags, we don't need to re-invent the wheel, because Scala has these amazing things called functions.

The above example prints:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<img src="www.mysite.com/imageOne.png" />

<div>

<p>This is the first image displayed on the site</p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="content">

<p>blah blah blah i am text</p>

<div>

<img src="www.mysite.com/imageTwo.png" />

<div>

<p>This image is very interesting</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>val evilInput1 = "\"><script>alert('hello!')</script>"

val evilInput2 = "<script>alert('hello!')</script>"

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1(

title:=evilInput1,

"This is my title"

),

evilInput2

)

)By default, any text that's put into the Scalatags templates, whether as a attribute value or a text node, is properly escaped when it is rendered. Thus, when you run the following snippet, you get this:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1 title=""><script>alert('hello!')</script>">

This is my title

</h1>

<script>alert('hello!')</script>

</body>

</html>As you can see, the contents of the variables evilInput1 and evilInput2 have been HTML-escaped, so you do not have to worry about un-escaped user input messing up your DOM or causing XSS injections. Furthermore, the names of the tags (e.g. "html") and attributes (e.g. "href") are themselves validated: passing in an invalid name to either of those (e.g. a tag or attribute name with a space inside) will throw an IllegalArgumentException).

If you really want, for whatever reason, to put unsanitized input into your HTML, simply surround the string with a raw tag:

val evilInput = "<script>alert('hello!')</script>"

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

raw(evilInput)

)

)prints

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<script>alert('hello!')</script>

</body>

</html>As you can see, the <script> tags in evilInput have been passed through to the resultant HTML string unchanged. Although this makes it easy to open up XSS holes (as shown above!), if you know what you're doing, go ahead.

There isn't any way to put unescaped text inside tag names, attribute names, or attribute values.

def page(scripts: Seq[Node], content: Seq[Node]) =

html(

head(scripts),

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div("content".cls)(content)

)

)

page(

Seq(

script("some script")

),

Seq(

p("This is the first ", b("image"), " displayed on the ", a("site")),

img(src:="www.myImage.com/image.jpg"),

p("blah blah blah i am text")

)

)Again, this is something that many other templating languages have their own special implementations of. In ScalaTags, this can be done simply by just using functions! The above snippet gives you:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div class="content">

<p>This is the first <b>image</b> displayed on the <a>site</a></p>

<img src="www.myImage.com/image.jpg" />

<p>blah blah blah i am text</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>class Parent{

def render = html(

headFrag,

bodyFrag

)

def headFrag = head(

script("some script")

)

def bodyFrag = body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p("This is my first paragraph"),

p("This is my second paragraph")

)

)

}

object Child extends Parent{

override def headFrag = head(

script("some other script")

)

}

Child.renderMost of the time, functions are sufficient to keep things DRY, if you for some reason want to use inheritance to structure your code, you probably already know how to do so. Again, unlike other frameworks that have implemented complex inheritance systems themselves, Scalatags is just Scala, and it behaves as you'd expect.

<html>

<head>

<script>some other script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<p>This is my first paragraph</p>

<p>This is my second paragraph</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>def uppercase(node: Node): Node = {

node match{

case t: HtmlTag => t.copy(children = t.children.map(uppercase))

case r: RawNode => r

case StringNode(v) => StringNode(v.toUpperCase)

}

}

html(

head(

script("some script")

),

uppercase(

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p(onclick:="... do some js")(

"This is my first paragraph"

),

a(href:="www.google.com")(

p("Goooogle")

)

)

)

)

)Again, this is something that many other templating frameworks have ad-hoc implementations of. In Scalatags, this can be handled entirely by a simple function. The above snippet both uses and defines a transformer that converts all text within it to uppercase. The transformer function (uppercase) recursively walks the given fragment, upper-casing any StringNodes it find. This prints the result below:

<html>

<head>

<script>some script</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>THIS IS MY TITLE</h1>

<div>

<p onclick="... do some js">

THIS IS MY FIRST PARAGRAPH

</p>

<a href="www.google.com">

<p>GOOOOGLE</p>

</a>

</div>

</body>

</html>The above example is frivolous, but demonstrates how you can implement and use filters to perform bulk-transforms on your Scalatags fragments before rendering them. This is something you should not need to do very often, but is pretty simple to do should you need it. Here's a more involved example, which uses a Regex to identify URLs in the body text and converts them into links:

def autoLink(node: Node): Seq[Node] = {

node match{

case t: HtmlTag => Seq(t.copy(children = t.children.flatMap(autoLink)))

case r: RawNode => Seq(r)

case StringNode(v) =>

val regex = "(https?|ftp|file)://[-a-zA-Z0-9+&@#/%?=~_|!:,.;]*[-a-zA-Z0-9+&@#]".r

val text = regex.split(v).map(StringNode)

val links =

regex.findAllMatchIn(v)

.map(_.toString)

.map{m => a(href:=m)(m)}

.toSeq

text.zipAll(links, StringNode(""), StringNode(""))

.flatMap{case (x, y) => Seq(x, y)}

.reverse

}

}

html(

head,

autoLink(

body(

h1("This is my title"),

div(

p(

"This is my first paragraph on http://www.github.com wooo"

),

"I love http://www.google.com"

)

)

)

)Again, this is a full example showing both the usage and the definition of the autoLink filter. This prints the below HTML:

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<div>

<p>

This is my first paragraph on

<a href="http://www.github.com">http://www.github.com</a> wooo

</p>

I love <a href="http://www.google.com">http://www.google.com</a>

</div>

</body>

</html>| Template Engine | Renders |

|---|---|

| Scalatags | 7436041 |

| scala-xml | 3794707 |

| Twirl | 1902274 |

| Scalate-Mustache | 500975 |

| Scalate-Jade | 396224 |

These numbers are the number of times each template engine is able to render (to a String) a simple, dynamic HTML fragment in 60 seconds.

The fragment (shown below) is designed to exercise a bunch of different functionality in each template engine: functions/partials, loops, value-interpolation, etc.. The templates were structured identically despite the different languages used by the various engines. All templates were loaded and rendered once before the benchmarking begun, to allow for any file-operations/pre-compilation to happen.

The numbers speak for themselves; Scalatags is almost twice as fast as splicing/serializing scala-xml literals, almost four times as fast as Twirl, and 10-15 times as fast as the various Scalate alternatives. This is likely due to overhead from the somewhat bloated data structures used by scala-xml (which Twirl also uses) and the heavy-use of dictionaries used to implement the custom scoping in the Scalate templates. Although this is a microbenchmark, and probably does not perfectly match real-world usage patterns, the conclusion is pretty clear: Scalatags is fast!

This is the Scalatags fragment that was rendered:

val contentpara = "contentpara".cls

val first = "first".cls

def para(n: Int) = p(

contentpara,

title:=s"this is paragraph $n"

)

val titleString = "This is my title"

val firstParaString = "This is my first paragraph"

html(

head(

script("console.log(1)")

),

body(

h1(color:="red")(titleString),

div(backgroundColor:="blue")(

para(0)(

first,

firstParaString

),

a(href:="www.google.com")(

p("Goooogle")

),

for(i <- 0 until 5) yield para(i)(

s"Paragraph $i",

color:=(if (i % 2 == 0) "red" else "green")

)

)

)

).toString()The rest of the code involved in this micro-benchmark can be found in PerfTests.scala

The primary data structure, the HtmlTag:

case class HtmlTag(tag: String,

children: List[Node],

attrs: SortedMap[String, String],

void: Boolean) extends Nodeis a simple, immutable representation of a single HTML tag. It's .apply() method takes a list of Modifier objects, which are really objects with a single transform: HtmlTag => HtmlTag method. These transforms are applied to the HtmlTag sequentially, returning a new HtmlTag at the end of the process.

The current selection of Modifier (or implicitly convertable) types include

- HtmlTags and

Strings: appends itself to the parent'schildrenlist. - AttrPairs: sets a key in the parent's

attrslist. - StylePairs: appends the inline

style: value;to the parent'sstyleattribute.

Although these are the Modifiers which are provided, it is possible to come up with your own custom Modifiers which do a variety of different things to the HtmlTag. All it has to do is provide a transform: HtmlTag => HtmlTag method, and it can do whatever it wants to the HtmlTag being transformed, including:

- Adding multiple attributes at once

- Adding both attributes and children at once

- Modifying existing attributes

- Modifying or filtering the list of children

The bulk of Scalatag's ~5000 lines of code is static bindings (and inline documentation!) for the myriad of CSS rules and HTML tags and attributes that exist. The core of Scalatags lives in Core.scala, with most of the implicit extensions and conversions living in package.scala.

Scalatags was made after experience with a broad range of HTML generation systems. This experience (with both the pros and cons of existing systems) informed the design of Scalatags.

Jinja2 is the templating engine that comes bundled with Flask, a similar (but somewhat weaker) system comes bundled with Django, and another system in a similar vein is Ruby on Rail's ERB rendering engine. This spread more-or-less represents the old-school way of rendering HTML, in that they:

- Are effectively string-based

- Use special syntax for both interpolating variables as well as for basic control flow logic

- Have a ruby/python-like (but not quite!) language for logic within the template

- Are generally with one template per file.

They also showcase many of the weaknesses of this style of templating system:

- The fact that it's string based means it's vulnerable to XSS injections, or plain-old malformed HTML output.

- The one-template-per-file rule discourages you from building your page from small re-usable fragments, because who wants to keep track of hundreds of individual files. People are reluctant to make a file with 3-5 lines in it, which is understandable but unfortunate because factoring templates into re-usable 3-5 line snippets is a good way of staying sane.

- The API is complex and novel: Jinja2 for example contains logic around file-loading & caching, as well as custom Jinja2-specific ways of doing loops, conditionals, functions, comments, inheritance, scoping, imports and other things. All these are things you would have to learn.

- The syntax is completely new; finding a editor that properly supports all the quirks and semantics (or even simply highlighting things properly) is hard. You could hack together something quick and extremely fragile, or you could wait ages for a solid plugin to materialize.

- Abstraction is clunky: inbuilt tags are used via

<div />, while user-defined components are called e.g. by{{ component() }}. You're left with a choice between not using much abstraction and mainly sticking to inbuilt tags, or creating components and accepting the fact that your templates will basically be totally composed of{{ curly braces }}. Neither choice is satisfying. - Have no sort of static checking at all; you're just passing dicts around, and waiting for silly mistakes to blow up at run-time so you can fix them.

Razor (the ASP.NET MVC template engine) and the Play framework's template engine go in a new direction. Their templates generally:

- Are statically-compiled

- Re-use large chunks of the host language

Both templating systems generally use @ to delimit "code"; e.g. @for(...){...} declares a for-loop. Nice things are:

- The API is far simpler: all the custom control-flow/logic/syntax basically collapses into the simple statement "do it the way C#/Scala does it".

- Static checking in templates is nice.

However, they still have their downsides:

- Abstractions are less clunky to use than in old-school templates, e.g.

@component()rather than{{ component() }}, but still not ideal. - The one-template-per-file rule is still there, making abstractions clunky to define.

- They still require their own special build-system-integration, run-time compilation, caching, and other things, which a templating language really shouldn't need. Scalate, which has a runtime dependency on the entire Scala compiler, suffers from the same problem.

- The syntax still poses a problem for editors; both HTML editors and C#/Scala editors won't want to work with these templates, so you still end up with sub-par support or waiting for plugins.

- You still end up with weird edge cases due to the fact that you're squashing together two completely unrelated syntaxes.

XHP and Pyxl are HTML generation systems used at Facebook and Dropbox. In short, they allow you to:

- Embed sections of your HTML as literals within your PHP and Python code

- Reference them as objects (e.g. calling methods and modifying fields)

- Provide a way to interpolate values and combine them.

The Pyxl homepage provides this example:

image_name = "bolton.png"

image = <img src="/static/images/{image_name}" />

text = "Michael Bolton"

block = <div>{image}{text}</div>

element_list = [image, text]

block2 = <div>{element_list}</div>Which shows how you can generate HTML directly in your python code, using your python variables. These libraries are basically the same thing, and have some nice properties:

- The one-template-per-file rule is gone! This encourages you to make more, smaller fragments and then compose them, which is great.

- They're no longer string-based, so you won't have problems with XSS or malformed output.

- The API is really simple; maybe a dozen different things you need to remember, and the rest is "just use Python/PHP". E.g. they don't need to load templates from the filesystem any more (with all the associated discovery/loading/caching logic) since it's all just in your code.

- The syntax is completely familiar too; apart from maybe one new rule (using

{...}to interpolate values) the rest of your templates and logic are bog-standard HTML/Python/PHP. - Abstraction is almost seamless; both systems allow you to define custom components and have them called via

<component arg="..." />

But they're not quite there:

- Although the syntax is familiar to you, it's not familiar to your editor, and probably will mess up your syntax highlighting (and other tooling) in your Python/PHP files.

- Defining custom components (e.g. in Pyxl) is much more verbose/tedious than it needs to be. Most of the time, all you want is a function; very rarely do you want a fragment that is long lived and has mutable state, which is where classes/objects are really necessary.

- Even using custom components gets tedious; at some scale, everything you pass into a component will be a structured Python value rather than a string, and you end up with code like

<component arg1="{value1}" arg2="{value2}" arg3="{value3}" arg4="{value4}" />. It's nice to have inbuilt/custom components behave uniformly, but you wonder what the XML syntax is really buying you other than forcing you to only use keyword-arguments and to wrap arguments in"{...}". - It's still XML! People spend a lot of time trying to get XML out of their templates; it seems odd to spend just as much time trying to put it into your source code.

And that's why I created Scalatags:

- Structured and immune to malformed output/XSS.

- No more one-template-per-file rule; make small templates to your hearts content!

- Dead-simple API, which re-uses 100% of what you know about Scala's language and libraries.

- 100% Scala syntax; no more bumping into weird edge cases with the parser.

- Syntax highlighting, error-highlighting, jump-to-definition, in-editor-documentation, and all the other nice IDE features out of the box. No more waiting for plugins!

- Inbuilt and custom tags are uniformly just function calls (e.g.

div("hello world")) - Custom components are trivial to create (

def component(x: Int, y: Int) = ...) and trivial to use (component(value1, value2)) because they're just functions. - No dependencies! No need for SBT integration, filesystem loading, runtime compilation, caching, and all that jazz. You create a Scala object, call

.toString(), and that's it!

On top of fixing all the old problems, Scalatags targets some new ones:

- Typesafe-ish access to HTML tags, attributes and CSS classes and styles. No more weird bugs due to typos like

flaot: leftor<dvi>. - Cross compiles to run on both JVM and Javascript via ScalaJS, which is a property few other engines (e.g. Mustache) have.

- Blazing fast

Scalatags is still a work in progress, but I think I've hit most of the pain points I was feeling with the old systems, and hope to continually improve it over time. Pull requests are welcome!

The MIT License (MIT)

Copyright (c) 2013, Li Haoyi

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.