- Aims of the Design Pattern

- Video

- The Problem

- The Solution

- Code Along

- Design Problems

- How the Object get its components

- How do the components interact/communicate with each other?

- Conclusion

The aims of the 'Component' design pattern is to allows for the decoupling of domains from their entities allowing them to span multiple domains. Decoupling allows for code reusability and allows developers to work on different sections of the code at the same time.

Our player for the video doesn't seem to work so here is the link

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/_FCfNAjaJAE" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>Say we developed a 'character' who moves on player input, is animated on screen and interacts with the environment. Naturally we want to put everything that involves our character into one class so its all contained. This sounds like a good idea but this will end up in us having to duplicate lots of code between characters. It also means if we want to change one part of a character we have to alter the same function, exposing lots more possible errors and makes them harder to track. For example, if we want to update the physics of a character, we would be making changes in the same function as the graphics.

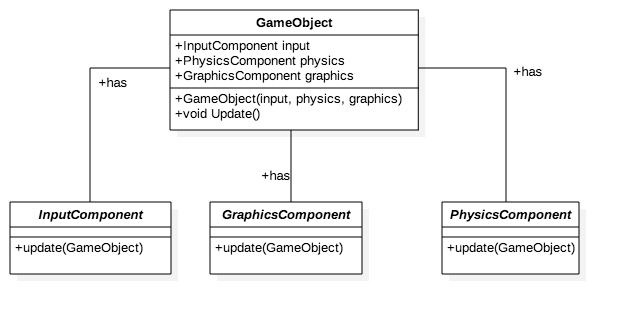

The solution to this problem is to separate out functionality into multiple components. A character is transformed into a GameObject, with multiple components that inherit from abstract interfaces. These abstract interfaces may cover functionality such as graphics and rendering, physics, and input.

In the following demo, we provide an implementation of the Component design pattern by starting off with a sub-optimal solution. The following solution implements the protagonist of our game who we will call Fred The Frog. In our game we want to be able to move Fred the Frog around our screen and not be able to bump into other objects on the map. We also want him to be able to be animated so it is clear what he is doing. This is a somewhat realistic scenario of what we expect most objects in our game to be able to do in some capacity.

We start with a rigid class that is inflexible as seen below.

class FredTheFrog {

public:

// Constructor

// Doesn't need any parameters as we know how we want Fred to Be and Act

FredTheFrog() {

velocityX = 0;

velocityY = 0;

x = 0;

y = 0;

acceleration = 1;

still = new Sprite("frog.png");

leftWalking = new Sprite("frogleft.png");

rightWalking = new Sprite("frogright.png");

}

~FredTheFrog() {}

// Update function that we will add to the Game Loop to get called every loop iteration.

void update(Map* map) {

// Make changes based on keyboard inputs

if (INPUT::getKeyDown() == "w") {

velocityY -= acceleration;

} else if (INPUT::getKeyDown() == "a") {

velocityX -= acceleration;

} else if (INPUT::getKeyDown() == "s") {

velocityY += acceleration;

} else if (INPUT::getKeyDown() == "d") {

velocityX += acceleration;

}

// Alter the location of Fred and resolve collisions.

x += velocityX;

y += velocityY;

map->sortCollisions(this*);

// Display the correct sprite of Fred on the screen

if (velocityX==0) { still.draw(x,y); }

else if (velocityX>0) { rightWalking.draw(x,y); }

else if (velocityX<0) { leftWalking.draw(x,y); }

}

private:

// We say (0,0) is the top left

int velocityX, velocityY, x, y, acceleration;

// We say that the sprite class is already implemented for this tutorial

Sprite* still;

Sprite* leftWalking;

Sprite* rightWalking;

}This code will run and work as expected. However, the problem occurs when we try and extend our class or alter it. We will also find ourselves writing lots of similar code if we decide to write another character.

To overcome this problem we are going to split this code up into components. We are going to reuse all of the code just separate it into different classes that can be reused in other places.

We will start off by writing the Physics Component.

class FredPhysicsComponent {

public:

// Constructor and Destructor

FredPhysicsComponent();

~FredPhysicsComponent();

// Update function

void update(FredTheFrom& fred, Map& map){

fred.x += fred.velocityX;

fred.y += fred.velocityY;

map.sortCollisions(fred);

}

}We can see that we write the physics component so that is just has a simple update function. As the physics gets more complicated you can add functions within the component without worrying about getting it mixed in with code we don't want it too.

Next we will move onto the Graphics Component

class FredGraphicsComponent {

public:

// Constructor that stores the game sprites

FredGraphicsComponent() {

still = new Sprite('frog');

walkingLeft = new Sprite('frogLeft');

walkingRight = new Sprite('frogRight');

}

~FredGraphicsComponent();

//Update function

void update(FredTheFrog& fred){

if(fred.velocityX==0){ still.draw(x,y); }

else if(fred.velocityX>0){ rightWalking.draw(x,y); }

else if(fred.velocityX<0){ leftWalking.draw(x,y); }

}

private:

Sprite& still;

Sprite& walkingLeft;

Sprite& walkingRight;

}Again we can see that the graphics component also just has a simple update function that runs the physics part of fred when called.

The last piece of the puzzle is keyboard input. We again can split this into a module as follows.

class FredInputComponent {

public:

FredInputComponent(){

acceleration = 1;

};

~FredInputComponent();

void update(FredTheFrog& fred){

if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "w"){

fred.velocityY -= acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "a"){

fred.velocityX -= acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "s"){

fred.velocityY += acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "d"){

fred.velocityX += acceleration;

}

}

private:

int acceleration;

}Now we can easily bring all these things together into a very small class that makes up fred. This is shown below

class FredTheFrog {

public:

FredTheFrog(){

physicsComponent = new FredPhysicsComponent();

graphicsComponent = new FredGraphicsComponent();

inputComponent = new FredInputComponent();

}

~FredTheFrog(){}

void update(Map& map){

// Update components

inputComponent.update(this*);

physicsComponent.update(this*, map);

graphicsComponent.update(this*);

}

private:

// We say (0,0) is the top left

int velocityX, velocityY, x, y;

// Here we store our components

PhysicsComponent& physicsComponent;

GraphicsComponent& graphicsComponent;

InputComponent& inputComponent;

}We can clearly see now that the code we have now for FredTheFrog is much simpler and if we want to find a certain part of Fred we can now do it very quickly. However, this solution only goes part of the way to solving the problem. If we want to use the code again for another game character we can't as they components are all specific to FredTheFrog. We also will have trouble when we want things to know about our characters as they will all be different classes.

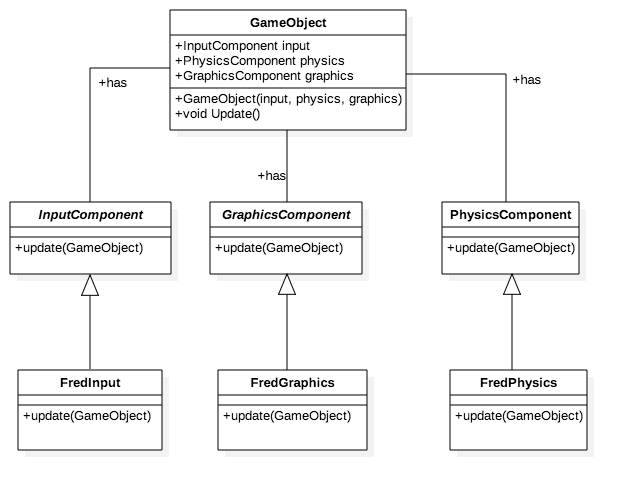

We can solve this problem by using abstract classes and this is when the design pattern really starts to be come more general and much more flexible to use. Below we can see the UML diagram of how to represent this.

We have a GameObject that we then instance whenever we want to have an object or character in our game, Fred would be a GameObject. The game object then stores all the components needed to make it up. It stores the abstract classes so you can implement your components by extending any given component. In the UML diagram we can see that we extend the components for Fred but you can write components so they are reusable so we could have a reusable graphics component by making the sprites modifiable. Below is how the Fred would work if we used these abstract classes.class GameObject(){

public:

GameObject(PhysicsComponent& physics, GraphicsComponent& graphics, InputComponent& input){

physicsComp = physics;

graphicsComp = graphics;

inputComp = input;

}

~GraphicsComponent();

void update(){

physicsComp.update(*this);

graphicsComp.update(*this);

inputComp.update(*this);

}

private:

PhysicsComponent& physicsComp;

GraphicsComponent& graphicsComp;

InputComponent& inputComp;

}

class InputComponent {

public:

// Virtual in CPP means these functions are abstract and need to be extended

virtual InputComponent();

virtual ~InputComponent();

virtual void update(GameObject& obj);

}

// In CPP this means that FredInput now extends the InputComponent

class FredInput : public InputComponent {

public:

FredInput();

~FredInput();

void update(GameObject& fred) {

if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "w"){

fred.velocityY -= fred.acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "a"){

fred.velocityX -= fred.acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "s"){

fred.velocityY += fred.acceleration;

}else if(INPUT::getKeyDown() == "d"){

fred.velocityX += fred.acceleration;

}

}

}

// Abstract Physics Component

class PhysicsComponent {

public:

// Must be extended

virtual PhysicsComponent();

virtual ~PhyscialComponent();

virtual void update(GameObject& obj, Map& map);

}

// Extending physicsComponent

class FredPhysics : public PhysicsComponent {

public:

FredPhysics();

~FredPhysics();

void update(GameObject& fred, Map& map){

fred.x += fred.velocityX;

fred.y += fred.velocityY;

map.sortCollisions(fred);

}

}

// Abstract Graphics

class GraphicsComponent {

public:

virtual GraphicsComponent(Sprite& stillSprite, Sprite& leftWalking, Sprite& rightWalking);

virtaul ~GraphicsComponent();

virtaul void update(GameObject& obj);

private:

Sprite& still;

Sprite& left;

Sprite& right;

}

// Extends Graphics for Fred

class FredGraphics : public GraphicsComponent {

public:

FredGraphics(Sprite& stillSprite, Sprite& leftWalking, Sprite& rightWalking){

still = stillSprite;

left = leftWalking;

right = rightWalking;

}

~FredGraphics();

void update(GameObject& obj){

if(fred.velocityX==0){ still.draw(fred.x,fred.y); }

else if(fred.velocityX>0){ right.draw(fred.x,fred.y); }

else if(fred.velocityX<0){ left.draw(fred.x,fred.y); }

}

}

GameObject& MakeFred(){

Sprite& still = new Sprite("frog.png");

Sprite& left = new Sprite("frogLeft.png");

Sprite& right = new Sprite("frogRight.png");

auto fredPhys = new FredPhysics();

auto fredGraph = new FredGraphics(still, left, right);

auto fredInput = new FredInput();

return new GameObject(fredPhys, fredGraph, fredInput);

}This solution looks large and cumbersome but if you are writing lots of characters doing similar things you can then build your game up in much more of a simple way.

You need to think about components you want and need. This will depend on your game. The more tangled and bigger the game the more thought out the components they need to be.

You also need to think about :

So we have a pile of separate components - who assembles them into a class?

The object always has the components it needs to run. Never have to rely on other people in wiring up the right components up to the container object.

The problem with this is its then harder to reconfigure the object. When we hard code the set of components we want we aren’t using the flexibility that can come with this pattern as you will see in the next segment.

What we mean by this is if when a class is creating a container object it passes the components you want it to use. This is helpful as the object becomes more flexible as the behaviour can be completely different depending on the components we feed it.

Also the object can be decoupled from the component types as if we are passing in the component types we can probably pass in derived component types. So we can just pass the component interfaces so we get nice encapsulation.

So these completely decoupled components sound perfect in our head but really don’t work in the real world. They are part of the same object and so need to communicate between each other to link up the processes.

There is multiple ways you can do this and they aren’t exclusive - you can put more than one in your designs.

It keeps the components totally decoupled but for a price as it requires any information shared to be shared to all components as the information gets pushed up to the container object. This makes the container object far more complex as most of the information will be specific to a few components.

It also means that any computation on the state is dependent on which order the components are processed. This sort of shared state with components reading the same data is very hard to get right and can introduce a lot of subtle bugs.

So we sort of take a step back to our monolithic class and introduce a direct reference to the components that need to talk to each other. For instance the animation component could have a reference to FredTheFrog’s physics component.

This is really simple and fast to implement but now these two components are tightly coupled together. It’s not great but it isn’t as nasty as the monolithic class as we are only creating links between the components that need the links.

The most complex sadly. We build a small messaging system into our container object to let components send messages. So the component sends a message to the container and the container sends it to all the components! This means that The components are decoupled again as the coupling is the messaging system that is in place.

The container object is simple again. All the container does is pass messages around and does not know about the data the components have at all unlike in shared state communication.

All ways have their uses so you will generally end up using them all in your game if you use the component pattern. The shared state is really good for simple stuff that every component might need.

Letting the components refer to each other directly is handy when the component are closely related. Sometimes it’s just easier letting these closely related components know about each other.

Messaging is good for communication that doesn’t need to be fired back and forth. So like switches that change the games state for instance.

The component pattern can add complexity instead of just making a class. Be careful because using components also means all the parts have to be instantiated and integrated together. That means a lot of memory management complexity that you have introduced, but in the long term with a large code base it will really help with decoupling for easier maintainability and extension later on. This can be really helpful in games programming as generally you are going to have scrap code regularly as you realise you don’t need that functionality in the game. Instead of having to dive into big monolithic classes to figure out which parts you don’t need it’s simpler just retiring some components inside an entity class. Having components allows you to have pile of functionality in predefined blocks you can simply add to new game objects and allows for more simply extension after you realise a behaviour needs extending.

Before finishing up do the quiz to see how much you have learned!

We hope that you can use the Component Pattern inside your own games to great effect! Thank you for reading.

Examples of this in the real world can come from the game engine Unity which uses the component pattern for its game objects.