- What is REST?

REST is an acronym for Representational State Transfer and an architectural style for distributed hypermedia systems.

- What is a REST API?

A Web API (or Web Service) conforming to the REST architectural style is a REST API.

- What is the architectural style then?

It is based on six principles:

Rest is resources oriented, so is important to identify a right level of abstraction of the resources involved and their interactions.

Clients and Servers can evolve isolated since the concerns are separated (but keeping in mind the interface must be respected) The main idea is to separate the user interface concerns (client) from the data storage concerns (server)

The server can't store any session at their side, so every request made to the server needs to contain all the information, to allow to the server to execute the requested action properly.

So the session state needs to be keep at client side

Retrieving resources should be cacheable. (This is why using a Body Payload for a GET call is considered a bad practice)

In Rest it is fine to hold the API in a server "A" and then save the resources in a server "B" (and even having the security in a server "C")

All the above constraints help you build a truly RESTful API, and you should follow them. Still, at times, you may find yourself violating one or two constraints. Do not worry; you are still making a RESTful API – but not “truly RESTful.”

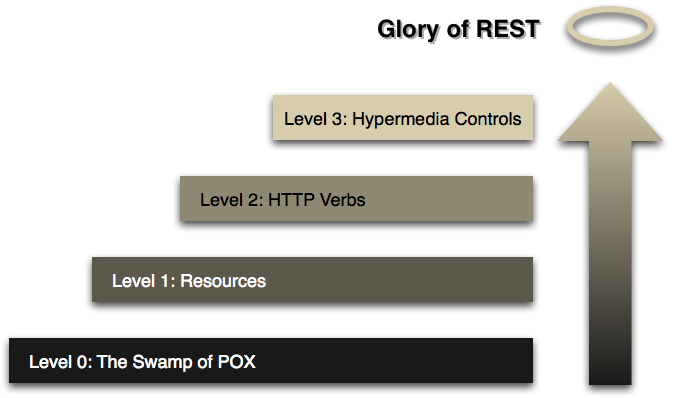

Is a way to measure how mature is your REST Api based on 4 models, from 0 to 4. I'd like to encourage this is not a standard. In fact, there is no standard defined to say if a REST Api is good enough or not. But the truth is, the Richardson Maturity Model was quickly adopted by the IT Industry, at least ot have "something to follow" to let you know you're doing well

If you have an API defined over the Https protocol to transfer data, then you are already in that level. It's free!

This level aims for having a good abstraction level based on resources. Following the plural over the singular, and not including verbosity at any endpoint

Examples of good naming ✅

- /employees

- /departments

- /employees/9e0343b9-a873-4db7-813e-fdeb68305d3b/departments

- /candidates/search?name=jhon&page=1&offset=20

The first endpoint can be used to create/update a single employee, or even to retrieve all the collection

The second endpoint is similar to the first one, but based on departments

The third can be used to update the departments of a given employee. Also, to retrieve the departments where the employee is added (if the key is found)

The last one is a search endpoint following the Google Semantic, it is retrieving the first page with only 20 candidates who are named as John

Examples of bad naming ❌

- /employee (not plural)

- /departments/create (verbosity is not allowed)

- /getEmployeeById (Please don't)

- /search?type=candidate&name=jhon&page=1&offset=20 (Avoid using flags, wrong abstraction level)

Now the right usage of Http Verbs and Http Status Codes are important.

Since the endpoint does not allow to be verbose, we have to use the right Http Verb to specify the kind of action we want to execute. In addition, is a good practice to choose the right Http Status Code to return if the action requested were succeeded or not.

- POST (Use POST only for creating new resources, please return 201) This operation is not idempotent

- GET (Use GET to retrieve data without changing the status of the server, please return 200, remember then it can be cached)

- PUT (Use PUT to update a whole existing resource in an idempotent way, please return 200)

- PATCH (Use PATCH to update partially an existing resource OR changing the state in a non-idempotent way OR implement a command that is out from the REST convention OR many other reasons... I just listed the most typical) This operation should not be idempotent

- DELETE (Use DELETE to remove a resource from the server, please return 200) This operation is not idempotent

As you notice is important to keep in mind the idempotency principle. Some operations must be idempotent by default, not others. If you are not familiar with idempotency, this is a mathematical principle that is saying you'll always have the same result, no matter how many times you execute it

Since this level adds complexity at client/server side. It is not recommended for small API's. Even some people consider it as an overkill, also it is better to keep the focus in the 2nd level for now

- About REST

- About Maturity Models

Level 2 is valid enough, you will find it in the 90% of the cases, so it is an acceptable approach, since it stands to encourage the good usage of namings (so then a right abstraction level) status codes a right verbs.

Even we could say the level 2 is the pragmatic one, since it is pushing for the having some best practices but avoiding the complexity of the level 3.

The next set of practices will help you to model a Rest Api focusing in the 2nd level and adding an extra layer of best practices to consider

It is important to identify the objects which they will be presented as resources in an agnostic manner.

One of the most common pitfalls, is to design the endpoints keeping the datasource on mind. I mean, imagine you have a Relational Database, and it contains VEHICLE, CAR, BIKE, PIECE, VEHICLE_PIECE... as examples

Then it is wrong to have dedicated endpoints for each table, specially if VEHICLE is so abstract, and it has no meaning by itself. So this is wrong:

-

/vehicles

-

/cars

-

/bikes

-

/pieces

Probably just /cars and /bikes would be enough, and to retrieve pieces you could model in this way:

-

/cars/pieces: To deal with the full catalog of pieces for cars

-

/bikes/pieces: To deal with the full catalog of pieces for bikes

-

/cars/{id}/pieces: To deal with the pieces they were used to manufacture a specific model of car

-

/bikes/{id}/pieces: To deal with the pieces they were used to manufacture a specific model of bike

In addition, you could have more than just a single data source, what if you have also to serve images that they are saved in a local volume named /vehicles/images ? Again don't map your API against your storage. Your interface must not be attached to those kinds of details, and it can be modelled in a different way. Examples:

- /images: full catalog of images if needed returning just the links to those images

- /cars/{id}/images: catalog of images for one car

Finally, is fine to have different endpoints which are modelling the same data in different ways. The data could have multiple representations, not just a single one. Examples:

- /cars/engines

There is no "engines" table, in fact an engine is a "big piece" so probably it is stored at PIECE table. But we're representing the engine as part of our API as an important resource.

Remember to don't make your API verbose. That means verbs are not allowed as part of the endpoint. Just use:

- POST: To create a new resource. The information about the new resource to create, is inside the payload (body) of the request. This operation is not idempotent that means, if you retry the request, it will create the same resource again with a different id. Be carefully with that.

curl -d '{"newCar":{"id":"abc-def-ghi","brand":"jkl-mn-opq","model":"New Model to hit the market!"}}' -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X POST http://server:port/v1/cars

- PUT: To update a whole existing resource. The information about the updated resource is inside the payload (body) of the request. This operation must be idempotent No matter how many times the PUT is executed, the result must be the same

curl -d '{"updatedCar":{"brand":"rst-abc-xyz","model":"Just renamed the model"}}' -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X PUT http://server:port/v1/cars/abc-def-ghi

-

GET: Use this verb for read only operations. Like Reading a single resource (GET /cars/{id}) or a collection (GET /cars) or when a search is executed (GET /cars/search?color=red&engine=1.6). Do not put anything as part of the body payload since GET must be cacheable, use always query params

-

DELETE: To delete a whole resource. Example: DELETE /cars/{id}

It is a very special verb, useful when:

- You can't design the endpoint in a REST way. Example: /bikes/{id}/active or /bikes/{id}/inactive

- You want to update a resource partially

- You can't ensure the idempotency of an update operation. Example: /bikes/{id}/toggle (which actives or not a bike, so it never would be idempotent)

Even it is not a real consensus about when to use Patch. It is heavily used when a command needs to be implemented. Here you have a further reading

-

Success:

- 201 - CREATED ➡️ Use it only when a new resource is "posted"

- 200 - SUCCESS ➡️ The request was processed succeeded at the server

-

Bad Request:

- 400 - BAD REQUEST ➡️ The server understood the request, but it failed. Use this Status when:

- The request has a lack of mandatory fields

- Or some fields are violating a business rule (what if I'm creating a car with only two wheels if four as the expected value for the server?)

- Or any other validation failed

- 401 - UNAUTHORISED ➡️ The requested resource/endpoint needs a previous authorisation and it was not found or expired

- 403 - FORBIDDEN ➡️ The authorisation is ok, but it has no permissions to access to the requested resource/endpoint

- 404 - NOT FOUND ➡️ The requested resource does not exist in the system.

- 400 - BAD REQUEST ➡️ The server understood the request, but it failed. Use this Status when:

-

Internal Server Errors:

- 500 - Internal ➡️ Well this should not be never thrown from our server since it means something was not taken into account

Again this is a default approach, sometimes could be great to return a different kind of status code (like 405 - Conflict) Always it will depend on the use case you're modelling. For further reading please check the whole list of Http Status Code

-

/cars - returns 201 if created ✅

-

/cars - returns 200 if created ❌

-

/cars - returns 400 if a validation failed and the car could not be created ✅

-

/cars - returns 403 if the requester has no permissions to create a new car ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 200 if updated ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 404 if abc-der-123 car does not exists ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 400 if a validation failed and the car could not be updated ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 403 if the requester has no permissions to update/delete an existing car ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 200 if car found ✅

-

/cars/search?color=red - returns 200 if red cars found ✅

-

/cars/search?color=green - returns 200 if green cars were not found ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 404 if abc-der-123 car does not exists ✅

-

/cars/abc-der-123 - returns 403 if the requester has no permissions to get an existing car ✅

-

/cars - returns 403 if the requester has no permissions to retrieve the whole collection of cars ✅

-

/cars/search?engine=electric - returns 403 if the requester has no permissions to search over the collection of cars ✅

As it is shown in some examples above, the id of the resource is heavily used in order to perform fetching/updating/deleting operations. So then, is not a good idea to have any kind of easy guessing id, like an incremental one. Because that id can be easily changed at the URL, and it could lead to a bad/wrong usage in order to receive non-allowed information of any other resource.

- /cars/6dd7f186-1ecb-11ed-861d-0242ac120002 ✅

- This is a hard guessing id, since even if the id gets changed at URI it would be hard to know a new valid id

- /cars/112 ❌

- This is wrong since a potential hacker could guess the id is autoincremental, and it could easily change the URL in order to check "what if I request 113 or 114"?

Finally, again don't mix up concepts. The way of modelling the API must be agnostic from data sources and so on. Don't think in the id like if it were your primary key of a table in a database. The table in the database could have its own primary key (autoincremental) but as a private one. The only thing you need to consider is to have a public way to fetch/update/delete resources.

Consider to use UUID for that purpose. Here you have some readings about it:

- https://www.at7.it/en/blog/rest_uuid_resource

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/31584303/rest-api-and-uuid

Sometime is fine to retrieve a whole collection of resources, to perform later filtering/sorting at client side. This approach is fine when you don't expect a heavy load of data. But when so much data is expected, like historic data, there is a big risk of killing the backend side, in order to receive requests that are hard to process.

So then, consider to use pagination at server side. Here you have a running example at this repo

Just imagine, you need to check against the datasource if a car that is going to be created can be created, for example you need to check if there is no other model for that car exactly as the car you want to save, you want to avoid duplicities. And if finally there is some kind of duplicity, then you need to return an error back from the server.

It was already mentioned, if that situation happens then we need to return a 400 Bad Request but it doesn't bring enough information to let us know what really happened with that request. Probably we want to show an error message (that need to be translated to different languages) or probably we want to highlight a field in our UI that is the responsible for having that failure at backend side.

To achieve that, we need a structure to follow to represent an error.

Even there is no standard define about how to return errors from Backend side, the industry recommends following the JSON Api approach.

Even it could be complicated, feel free to reduce/skip the amount of info to put inside the error structure. But at least try to follow that convention as much as possible. Avoid return just a plain text with a generic message

This pattern is coming from CQRS in fact, what it is suggested is just a part of CQRS. The main idea here is, there is nothing wrong in model the same concept of the API in different ways. And it is a good idea to separate the model used to fetch/collect data from the model used to write/update data.

The thing is, if just have a single "car" resource modelled in just one way, probably some clients will retrieve more data than expected. Example:

- GET /cars ➡️ can return a Car object, fully detailed

- GET /offroads ➡️ will return also cars, since a Offroad is a type of car, but modelled as an Offroad object, which has a different set of fields/attributes

Similar thing when you have a custom model for creating/updating a resource (a car) probably the data needed to create a generic car is different than the data needed to create a offroad. And even the data needed to update a whole resource probably is different than the data needed to create the resource.

So then is fine to have:

{

"car": {

"id": "abc-def-ghi",

"brand": "Volvo",

"model": "V40",

"engine": "v1.9 - 110cv - GAS",

"pieces": [

1,

2,

3

]

}

}

{

"offroad": {

"id": "abc-def-ghi",

"brand": "Volvo",

"model": "CX90",

"fourTractionWheels": true,

"extras": [

1,

2,

3

]

}

}

{

"newCar": {

"id": "abc-def-ghi",

"brand": "jkl-mn-opq",

"model": "New Model to hit the market!"

}

}

{

"updatedCar": {

"brand": "rst-abc-xyz",

"model": "Just renamed the model"

}

}

At least try to follow:

- Enable backward compatibility

- Keep the API Documentation updated to reflect new versions (or changes in the existing one)

- Adapt API versioning to business requirements

- Put API security considerations at the forefront

Keep in mind, in the most of the cases, you'll start with the version 1 of your API, and it will never be changed. Only create a new version when a breaking change is introduced. For example:

- A change in the format of the response data could break a caller

- A change in types used for requesting/response data (changing an integer to a float)

- Removing any part of the API

Non-breaking changes, such as adding new endpoints or new response parameters, do not require a change to the major version number.