Easy to use state machine to manage the state of python objects.

This state machine implementation is developed with the following goals in mind:

- Easy to use API, for configuration of the state machine and triggering state transitions,

- Usable for any (almost, I'm sure) python class with a finite number of states,

- Fully featured, including nested states, conditional transitions, shorthand notations, many ways to configure callbacks,

- Simple state machines do not require advanced knowledge; complexity of configuration scales with complexity of requirements,

- One state machine manages the state of all instances of a class; the objects only store their current state as a string,

- Option to use multiple interacting state machines in the same class, with no added complexity,

- Optimized for speed and memory efficient.

To install the module you can use: pip install states3. It has no external dependencies, except optionally graphviz for creating an image of your state machine.

This module only runs on Python >= 3.6.

The following basic state machine concepts are used:

- state machine: system that manages the states of objects according to predefined states and transitions,

- state: state of an stateful object; objects can be in one state at the time,

- transition: transition of the object from one state to another,

- trigger: (generated) method called on an object that triggers a state transition,

- callback: different functions called on state transitions by the state machine,

- condition: conditions that allow a specific state transition to take place.

Here is a simple state machine to give some idea of what the configuration looks like.

from states import state_machine, StatefulObject, states, state, transition

class LightSwitch(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('off', 'on'),

transitions=[

transition('off', 'on', trigger='flick'),

transition('on', 'off', trigger='flick'),

],

)

@state.on_entry('on', 'off')

def print(self, name):

print(f"{name} turned the light {self.state}")

lightswitch = LightSwitch(state="off")

lightswitch.flick(name="Bob") # prints: "Bob turned the light on"

lightswitch.flick(name="Ann") # prints: "Ann turned the light off" The module has the following basic and some more advanced features:

- enable triggering state transitions by setting trigger name(s) in machine configuration:

- same trigger can be set for different transitions,

- when a trigger method is called it passes its arguments to all callbacks (e.g.

on_exit,on_entry),

- conditional transitions can be used to change state depending on condition functions,

- if a transition is triggered, but the condition is not met, the transition does not take place

- to do this, create multiple transitions from the same state to different states and give them different conditions

- A large number of callbacks can be installed when needed. Examples are

on_entryof a state,on_exitof a stateon_transferon a specific transition between states,conditionon a transition. More info in the section "On Callbacks", - callbacks can be methods on the class of which the state is managed by the machine, with 2 options:

- The callback is configured as a string (e.g.

active=state("on_entry": "do_callback")) in state machine definition, that is looked op on the stateful class, - The callback is a decorated method of the class (e.g.

@machine.on_entry('active')withactivethe state name being entered),

- The callback is configured as a string (e.g.

- wildcards (

*) and listed states can be used to define (callbacks for) multiple transitions or at once:- for example transition

transition(["A", "B"], "C")would create 2 transitions, on from A to C and one from B to C;transition("*", "C")would create transitions from all states to C,

- for example transition

- nested states can be used to better organize states and transitions, states can be nested to any depth,

- multiple state machines can be used in the same class and have access to that class for callbacks, a single trigger can result in callbacks through multiple machines,

- a context manager can be defined on state machine level to create a context for each transition,

- constraints can be defined on a state, basically setting conditions on all transitions to that state,

- custom exceptions:

MachineError: raised at initialization time in case of a misconfiguration of the state machine,TransitionError: raised at run time in case of, for example, an attempt to trigger a non-existing transition,

- Basic support to draw states and transitions using

graphviz.

This section we will show an example that shows most of the features of the state machine. We will introduce features step-by-step.

Lets define a simple User class, say for getting access to an application:

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(...)

def __init__(self, username, state='somestate'):

super().__init__(state=state)

self.username = username

self.password = None- Class

StatefulObjectsets one class attribute and adds trigger methods to theUserclass when these are defined. state_machineis the factory function that takes a configuration and turns it in a fully fledged state machine.- Notice you can set the initial state through the

state(or any other name you gave the state machine), argument of__init__.

Let's add some states:

new: a user that has just been created, without password, etc.active: a user that is active on the server, has been authenticated at least once, ...blocked: a user that has been blocked access for whatever reason.

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('new', 'active', 'blocked')

)

def __init__(self, username):

super().__init__(state='new')

self.username = username

self.password = None

user = User('rosemary')

user.goto_active()

assert user.state == 'active'state_machinetakes a parameterstates, preferable created with thestatesfunction that returns a validated dictionary.- The initial state can be set as above; if not given, the first state of the state machine will be used as the initial state,

- When no transitions are explicitly defined, transitions will be automatically added to the state machine. All possible transitions and related triggers are generated and can be called as

goto_[statename](...), states('new', 'active', 'blocked')is shorthand forstates(new=state(), active=state(), blocked=state()); the longer form is only needed when extra configuration of the states is needed,

Most of the time you would want to define the transitions yourself, to configure them and to limit possible transitions (e.g. reduce the chance of users logging in without password).

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('new', 'active', 'blocked'),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

]

)

def __init__(self, username):

super().__init__(state='new')

self.username = username

self.password = None

user = User('rosemary')

user.activate()

assert user.state == 'active' # this is the current state of the user- We add a an argument

transitionsto the state machine with from- and to states, and a trigger name that can be called to trigger the transition. - The

transitionitems in thetransitionslist are validating functions returning a dictionary, - The transitions limit the possible transition between states to those with transitions defined on them; if e.g.

user.activate()was called again, aTransitionErrorwould be raised, because there is not transition between 'active' and 'active', - We also created a user, with initial state 'new' and triggered a transition:

user.activate(), after which the user had the new state 'active'. - trigger functions like

User.activate()andUser.block()are auto-generated during state machine construction, - Similarly, now the user has state 'active', we could call

user.block()and afteruser.unblock(), but only in that order, However, a user needs to have a password to be 'active'.

Lets use activate to set the password of the user (leaving out the __init__ method; it will stay the same for now):

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('new', 'active', 'blocked'),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

]

)

...

@state.on_entry('active')

def set_password(self, password):

self.password = password

user = User('rosemary')

user.activate(password='very_secret')

assert user.state == 'active'

assert user.password == 'very_secret'- The decorator

@state.on_entry('active')basically setsset_passwordto be called on entry of the stateactiveby the user. - Note that in

@state.on_entry, the name of the state machine attribute fromstate=state_machine(...)is used, - Remember that to go to the state 'active' the trigger function

user.activate(...)needs to be called:- All arguments passed to the trigger function will be passed to ALL callbacks that are called as a result,

- Tip: use keyword arguments in callbacks and when calling trigger functions in other than trivial cases,

- if there are multiple arguments needed by different callbacks, they can be defined like e.g.

callback(used_args, .., **ignored)to ignore all unneeded arguments by this callback, but possibly needed by others.

- We can similarly set callbacks for

on_exit,on_stay.

To make the possibilities of callbacks clearer, let's have some more:

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('new', 'active', 'blocked'),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

]

)

...

def set_password(self, password):

self.password = password

@state.on_entry('*') # on_entry of all states

def print_transition(self, **ignored):

print(f"user {self.username} went to state {self.state}")

@state.on_exit('active') # called when exiting the 'active' state

def forget_password(self, **ignored):

self.password = None

@state.on_transfer('active', 'blocked')

def do_something(self, **ignored):

pass- A wildcard

*can be used to indicate all states (or sub-states, as in 'active.*' , more on that later), - for callback decorators

on_entry,on_exitandon_stay, multiple comma separated states can be given (e.g.@state.on_exit('new', active')) and the callback will be installed on each state, - If an action is required on a specific transition, this can be achieved with

@state.on_transfer(old_state, new_state); if too manyon_transfercallbacks are required on a state machine, there might be a problem in the state definitions,

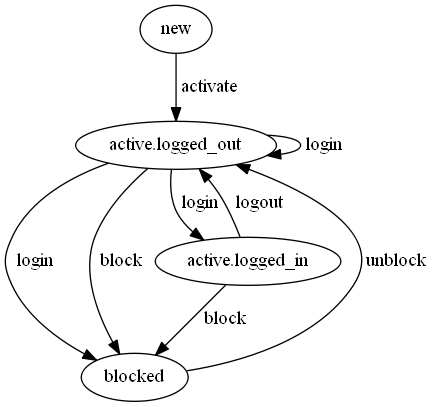

To make this state machine a bit more useful, let us include a basic login process. To do this we will add 2 sub-states to the 'active' state:

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition, state

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states('new', 'blocked',

active=state(states=states('logged_out', 'logged_in'))),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

]

)

...

@state.on_entry('active')

def set_password(self, password):

self.password = password- Notice

active=state(states=states('logged_out', 'logged_in')):- the sub_state has the same configuration as the main state machine,

- but instead of

state_machinewe will use the functionstatereturning a dictionary, - actual construction of the sub-states is left to the main

state_machine

- the transition

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate')will now put the user in theactive.logged_outstate (because it is first in the list of sub-states ofactive) - the transition

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block')will put the user in theblockedstate independent of theactivesub-state the user was in,

Of course the user needs to be able to login and logout and during login, a password must be checked:

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition, state

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states(

new=state(), # default: exactly the same result as using just the state name

blocked=state(),

active=state(

states=states('logged_out', 'logged_in'),

transitions=[

transition('logged_out', 'logged_in', trigger='log_in'),

transition('logged_out', 'logged_out', trigger='log_in'),

transition('logged_in', 'logged_out', trigger='log_out')

]

)

),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

]

)

...

@state.on_entry('active')

def set_password(self, password):

self.password = password

@state.condition('active.logged_out',

'active.logged_in')

def verify_password(self, password):

return self.password == password

@state.on_entry('active.logged_in')

def print_welcome(self, **ignored):

print(f"Welcome back {self.username}")

@state.on_exit('active.logged_in')

def print_goodbye(self, **ignored):

print(f"Goodbye {self.username}")

@state.on_transfer('active.logged_out',

'active.logged_out')

def print_sorry(self, **ignored):

print(f"Sorry, {self.username}, you gave an incorrect password")

user = User('rosemary').activate(password='very_secret').log_in(password='very_secret')

assert user.state == 'active.logged_in'

user = User('rosemary').activate(password='very_secret').log_in(password='wrong_secret')

assert user.state == 'active.logged_out'-

With

@state.condition(...)a conditional transition is introduced:- this means that the transition only takes place when the decorated method returns

True, - So, what if the condition returns

False?- During state machine initialization, a check for a default transition (without condition) takes place,

- if not found, an unconditional transition back to the original state is auto-generated,

- in this case, because we wanted to add the callback with

@state.on_transfer('logged_out', 'logged_out'), we needed to explicitly add this (default) transition to the state machine, - this transition is executed when the conditions fails.

- this means that the transition only takes place when the decorated method returns

-

Note that the triggers can be chained

User(...).activate(...).log_in(...), the trigger functions return the object itself, -

A function can have multiple callback decorators applied to it; also the same decorator can be applied to multiple callback functions,

-

This completes a basic state machine for the user flow for application access, it might seem little code, but it accomplished quite a lot:

-

The user must provide a password to become active,

-

the user must be active to be able to log in,

-

the user must provide the correct password to login,

-

the user is be provided with different feedback for each occasion,

-

the user can be blocked and unblocked and he/she cannot login when blocked.

-

**Intermezzo: another way to configure conditional transitions (and other callbacks) **

For clarity sake there is another way to configure conditional transitions:

from states import states, transition, state, case, default_case active=state( states=states('logged_out', 'logged_in'), transitions=[ transition('logged_out', [case('logged_in', condition='verify_password'), default_case('logged_out')], # stay in logged_out trigger='log_in'), transition('logged_in', 'logged_out', trigger='log_out') ] )

- The second argument of

transitionis replaced with a list of cases, indicating different end states of the transition,caseanddefault_caseare function that help configuration (e.g. validate); they define the states the transition might lead to and return dictionaries,condition='verify_password'refers to the methodverify_passwordon the state managed object. If the condition argument is a string it will be looked up on the (in this case) User class. If it's a function, it will be used as is,- Similarly other callbacks can be configured directly in the state machine config (not through decorators). For example you could do

active=state(on_entry='set_password'),- This way of configuration is especially useful for conditional transitions, because they are part of the 'structure' of the state machine; the other callbacks are (in my mind) better added through decorators, for clarity sake.

Let's extend the example one more time:

- We want to block the user after 5 failed login attempts (because 3 is soo limiting ;-)

- Let's add a 'deleted' state for users you want to get rid of (for some reason),

- Let's also add some logging, we want to know about state transitions,

- We'll leave out the messages, to keep focus on the task at hand.

import logging

from states import StatefulObject, state_machine, states, transition, state

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

class User(StatefulObject):

state = state_machine(

states=states(

new=state(), # default: exactly the same result as using just the state name

blocked=state(),

active=state(

states=states('logged_out', 'logged_in'),

transitions=[

transition('logged_out', 'logged_in', trigger='login'),

transition('logged_in', 'logged_out', trigger='logout')

]

),

deleted=state(),

),

transitions=[

transition('new', 'active', trigger='activate'),

transition('active', 'blocked', trigger='block'),

transition('active.logged_out', 'blocked', trigger='login'),

transition('blocked', 'active', trigger='unblock'),

transition('*', 'deleted', trigger='delete'),

]

)

def __init__(self, username, max_logins=5):

super().__init__(state='new')

self.username = username

self.password = None

self.max_logins = max_logins

self.login_count = 0

@state.on_entry('active')

def set_password(self, password):

self.password = password

@state.constraint('active.logged_in')

def verify_password(self, password):

return self.password == password

@state.condition('active.logged_out',

'blocked',

trigger='login')

def check_login_count(self, **ignored):

return self.login_count >= self.max_logins

@state.on_transfer('active.logged_out',

'active.logged_out')

def inc_login_count(self, **ignored):

self.login_count += 1

@state.on_exit('blocked')

@state.on_entry('active.logged_in')

def reset_login_count(self, **ignored):

self.login_count = 0

@state.after_entry()

def do_log(self, **ignored):

logger.info(f"user went to state {self.state}")

user = User('rosemary').activate(password='very_secret')

for _ in range(user.max_logins):

user.login('wrong')

assert user.state == 'active.logged_out'

user.login('wrong') # one time too many

assert user.state == 'blocked'- We count login attempts when the user goes from

active.logged_outback toactive.logged_outand reset the count on any successful login, - in

check_login_countwe check whether the login count has exceeded the maximum, - Notice that the decorator above

check_login_count()includes the triggerlogin, this is because there is another transition fromactive.logged_outtoblockedwith triggerblock. The state machine will raise aMachineErrorwhen there is more then a single possible transitions to add the condition to, - Notice also that we have replaced the

@state.condition('active.logged_out', 'active.logged_in')decorator with the@state.constraint('active.logged_in'), decorator; a way to restrict all transitions going into a state (active.logged_inin this case), - The

@state.after_entry('somestate')decorator applies to any entry of a (sub-) sub-state of the state. No argument means the root state machine:@state.after_entry(). Similarly there is@state.before_exit(...).

Options & Niceties

The state machine has a couple of other options and niceties to enhance the experience:

-

A prepare callback that if present will be called before any transition: the

@[state machine name].preparedecorator will install it on the machine. Note that the decorator takes no arguments, -

You can define more then 2 states in a single transition, for example:

transition('new', 'active.logged_out', 'active.logged_in', trigger='log_through')

This will call all related defined callbacks.

-

One or more context managers callback that if present, can create a context for all transitions: it can be installed as follows:

@[state machine attribute name].contextmanager('some_keyword') def some_context(obj, *args, **kwargs): ... # initialize context yield context ... # finalize context

Important: it will pass the context as a keyword argument to all callbacks called within the transitions (all but

prepare), so the callbacks must be able to take the defined keyword argument (in this casesome_keyword) argument, as in:@some_machine.on_exit('somestate') def some_callback(obj, some_keyword, ...): pass # do something with the context argument

or

@some_machine.on_exit('somestate') def some_callback(obj, some_args, **ignored): pass # ignore the context argument

If no keyword is given (as in

@some_machine.contextmanager()), no context will be passed to the callbacks, -

You can save the graph of the state machine in different file formats using

.save_graph(filename, **options)as in:User.state.save_graph('user_state.png') # see image at top of readme

The options are passed to

graphvizas the options for both nodes and edges, see graphviz.

Callbacks like on_entry are part of what makes the use of a state machine so powerful. Here we will give a full list of all callbacks, a way to add them to the state machine through decorators and when they will be called.

On callback arguments:

- all callbacks must have as first argument the object of which the state is managed; if the callback is a method on the class of the object, this is automatic: the

selfargument, - The callbacks are called as a result of calling a trigger on the state managed object (

user.activate(password=password)). All arguments with which the trigger is called are passed to all resulting callbacks, - otherwise callbacks can be defined with any arguments (

*args,**kwargs).

So in general the installation of a callback on a state machine looks something like this:

@[machine_name].[decorator_name](*state_names[, trigger='some_trigger'])

def some_callback(self, *args, **kwargs):

passSome notation:

- old_state, new state: the state before and after a transition,

- state_name: the (possibly

.separated) name of the state, - machine: the name of the complete state machine in this case (could be called anything).

With obj the state managed object and *args and **kwargs the arguments passed via the trigger to the callback, (not in calling order):

| name | decorator example | callback called |

|---|---|---|

| on_exit | @machine.on_exit('state_name') |

when the object exits a state during a transition |

| on_entry | @machine.on_entry('state_name') |

when the object enters a state during a transition |

| before_exit | @machine.before_exit('state_name') |

called before any exit within a sub-state of the argument state; state_name is optional, when absent the callback is called on any exit within the machine (e.g. for logging) |

| after_entry | @machine.after_entry('state_name') |

similar as above but called after any entry of sub-state |

| on_transfer | @machine.on_transfer('old_state', 'new_state') |

called when a transition from old_state to new_state takes place |

| on_stay | @machine.on_stay('state_name') |

called when a transition does no cause an exit of the state; also called on a parent state if a transition stays within that state |

| prepare | @machine.prepare |

no argument decorator, if present, always called at the start of any transition, (whether it succeeds or not) |

| contextmanager | @machine.contextmanager |

no argument decorator, if present is called just after prepare, used to create a context for the transition, which will be passed to the callbacks as parameter context (callbacks be ready). The callback should be a generator as used in the standard python @contextmanager decorator. |

| condition | @machine.condition('old_state', 'new_state', trigger='some') |

set a condition on a transition (trigger is optional for occasional disambiguation), called before a transition takes place, callback should return True or False |

| constraint | @machine.constraint('state_name') |

sets a constraint on entering the state, basically adds the callback as a condition on all transition going to the state. |

Notes:

- No callback is required, use as needed, mostly you can do what you want with only a few callbacks,

- None of these callbacks (apart from the

contextmanager), need to be a single method; if multiple callbacks are decorated for the same transition, there are added to a list of callbacks for that occasion, - A callback can be decorated with multiple decorators stacked, the bottom one will used first,

- The decorators do not change the callback in any way, they are not nested in another function, but returned as is,

- The 'state_name' can include wildcards

*meaning any sub-state,

Call order:

- In cases where the stateful object does not change state:

prepare,contextmanager,on_transfer,on_stay,parent.on_stay, ..., [exitcontextmanager], - For an actual state transition:

prepare,contextmanager, *,parent.before_exit,on_exit,[ actual state change],on_entry,parent.after_entry, [parent.on_stayfor any parents the transition does not exit],on_transfer, [exitcontextmanager], - Note the ***** in the above? This where the conditions on the transition and constraints on the new_state are checked. If one of these fail, another transition is checked, until the conditions pass, or there is no condition. The state machine is checked during construction for there always being a default condition-less transition to fall back to,

- In case of nested states, parent callbacks will also be called if applicable, e.g. if a user goes from

active.logged_outtoblocked:on_exitofactive.logged_outandon_exitofactivewill be called, because theactivestate is also exitted.

This state machine is pure python, but very optimized; on a normal PC a state transition with a single callback will take place in ~1 microsecond. The final performance is in most cases determined by the performance of the callbacks, although adding conditions, constraints and contextmanagers will add some extra overhead.

This is a new section of the readme, starting at version 0.4.0.

Features/Changes

- Transitions can be defines with more then 2 states,

- The

contextmanagerdecorator now takes a keyword for the name under which the context is passed to the callbacks, - Transitions directly back to the same state should be defined with a single state name.

Features

- more flexibility in configuration of conditional transitions (for some somewhat rare cases),

- Nicer graphs (with e.g. conditional transitions clearly shown).

Changes

- Some robustness/simplicity improvements, especially handling the alternative name case for e.g. SqlAlchemy.

Bug fixes

- fixes bug where no subclass of StatefulObject could be created without state machine.

Features

- adds

@machine.constraint('state_name')decorator.

Changes

- makes setting conditions more robust. Default transitions are added at the end of construction and no more conditions or constraints can be added after that point. This means that if a default transition needs a callback, it must be explicitly defined. Other callbacks can be added dynamically.

Features

- improved speed (~25%); simple state machine with single no-op callback now changes state in ~ 0.8 microseconds on intel i7 from 2016, with Win10.

Bug fixes

- method for calling

on_entrycallbacks after initializing the state of an object during construction is now consistent with previous fixes.

Bugfix release

Bug fixes

- small fix for lost code (must be tired) + extra test.

Enables easier integration with SqlAlchemy (and probably Django).

Features

-

add argument

name(defaultNonein which case nothing changes) to state machine configuration. This is the attribute name the state is stored under on the stateful object. For example useful as column name for use with SqlAlchemy, to enable querying on the state:class User(StatefulObject, SqlaBase): state = Column(String(32), nullable=False) machine = state_machine(name='state', ...) ... blocked_users = session.query(User).filter(User.state='blocked').all()

Bugfix release

Bug fixes

- fix in normalize in case of multiple old states and a condition.

Added extra decorators for convenience and some edge case:

Features

- add

before_exitandafter_entrydecorators.

A major overhaul, with many improvements, especially in configuration and performance:

Features

- simplified configuration and partial auto-generation of state-machine (minimally just using state names),

- adding callbacks to the state machine using decorators, instead of directly in the main configuration,

- much improved speed: a single transition with a single (minimal) callback now takes < 2 microseconds on a normal PC,

- basic option to create a graph from the state machine, using

graphviz, - better validation with improved error messages,

- Corrected and improved README.md (this document).

Changes

- configuration now uses validating functions instead of plain dictionaries and lists.

- Old configurations should still work, but no guarantees.

Bug fixes

- fixed incorrect calling of

on_exitin some cases. Introduced in 0.3.2. Do upgrade if you can.

Features

- trigger calls now return the object itself, making them idempotent:

object.trigger1().trigger2()works, - added an

on_staycallback option to states, called when a trigger is called which results in the state not changing. This andon_transferare the only callbacks being called in such a case.

Bug fixes

- no current bugs, please inform me if any are found

Changes

- when no transition takes place on a trigger call,

on_exit,on_entryetc. are not called anymore (on_transferwill be if defined).on_staycan be used to register callbacks for this case. This breaks backward-compatibility in some cases, but in practice makes the definition of the state machine a lot easier when callingon_exitetc. is undesirable when the actual state does not change. It makes configuration also a lot more intuitive (at least for me ;-). - trigger calls do not return whether a state change has taken place (a

bool), but the object on which the trigger was called, making them idempotent.

The state machine in the module has the following rules for setting up states and transitions:

- notation:

- (A, B, C) : states of a state managed object (called 'object' from now)

- (A(B, C)) : state A with nested states B, C,

- A.B : sub-state B of A; A.B is called a state path,

- <A, B> : transition between state A and state B,

- <A, B or C>: transition from A to B or C, depending on condition functions,

- <*, B>: shorthand for all transitions to state B,

- allowed transitions, given states A, B, C(E, F) and D(G, H):

- <A, B>: basic transition,

- <A,>: transition from state A to itself,

- <C.E, A>: transition from a specific sub-state of C.E to A,

- <C, D.G>: transition from any sub-state of C to specific state D.G,

- <A, C>: transition from A to C.E (if it exists), E being the default state of C because it was explicitly set or its the first state configured in E,

- <C.F, D.H>: transitioning from one sub-state in a state to another sub-state in another state. Note that this would call (if present) on_exit on F and C and on_entry on D and H in that order.

- adding conditional transitions, given transition <A, B or C or D>:

- <A, B> and <A, C> must have conditions attached, these condition will be checked in order of configuration;

- D has no condition attached meaning it will always be the next state if the conditions on <A, B> and <A, C> fail,

- (If <A, D> does have a condition attached, a default state transition <A, A> will be created during state machine construction),

- an object cannot just be in state A if A has sub-states: given state A(B, C), the object can be in A.B or A.C, not in A.

Lars van Gemerden (rational-it) - initial code and documentation.

See LICENSE.txt.