This repo introduces functional programming concepts using TypeScript and possibly libraries in the fp-ts ecosystem.

This fork is an edited translation of Giulio Canti's "Introduction to Functional Programming (Italian)". The author uses the original as a reference and supporting material for his lectures and workshops on functional programming.

The purpose of the edits is to expand on the material without changing the concepts nor structure, for more information about the edit's goals see the CONTRIBUTING file.

- What is functional programming

- The two pillars of functional programming

- Semigroups

- Eq

- Ord

- Monoids

- Pure and partial functions

- ADTs and functional error-handling

- Category theory

- Functors

- Applicative functors

- Monads

Though programming was born in mathematics, it has since largely been divorced from it. The idea is that there's some higher level than the code in which you need to be able to precisely, and that mathematics actually allows you to think precisely about it - Leslie Lamport

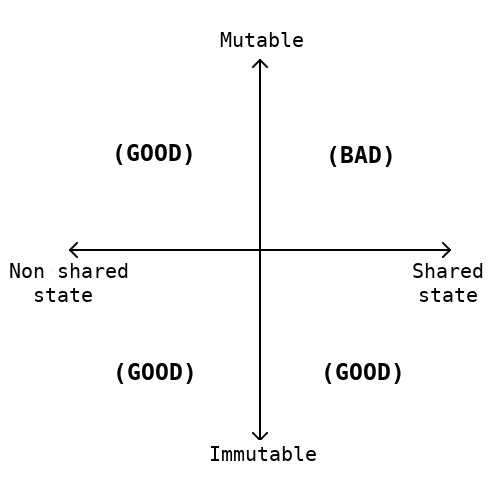

Functional programming's goal is to dominate a system's complexity through the use of formal models, careful attention is given to code's properties.

Functional programming will help teach people the mathematics behind program construction: how to write composable code, how to reason about effects, how to write consistent, general, less ad-hoc APIs

Example

Why's map "more functional" than a for loop?

const xs = [1, 2, 3]

function double(n: number): number {

return n * 2

}

const ys: Array<number> = []

for (let i = 0; i < xs.length; i++) {

ys.push(double(xs[i]))

}

const zs = xs.map(double)A for loop offers more flexibility: I can modify the starting index (initialization), the looping condition (condition), and the final expression.

This also implies that I may introduce errors and that I have no guarantee about the returned value.

A mapping function gives me several guarantees: all the input elements will be passed to the mapping function, regardless of the content of the callback function provided, the resulting array will always have the same number of elements of the starting one.

- Referential transparency

- Composition (as universal design pattern)

An expression is said to be referentially transparent if it can be replaced with its corresponding value without changing the program's behaviour

Example

function double(n: number): number {

return n * 2

}

const x = double(2)

const y = double(2)The expression double(2) benefits from referential transparency because it is replaceable with its value, the number 4.

const x = 4

const y = xNot every expression benefits from referential transparency, let's see an example.

Example

function inverse(n: number): number {

if (n === 0) throw new Error('cannot divide by zero')

return 1 / n

}

const x = inverse(0) + 1I can't replace inverse(0) with its value, thus it doesn't benefits from referential transparency.

Why is referential transparency so important? Because it allows us to:

- reason better about our code

- refactor without changing our system's behaviour

Example

declare function question(message: string): Promise<string>

const x = await question('What is your name?')

const y = await question('What is your name?')Can I refactor in this way?

const x = await question('What is your name?')

const y = xFunctional programming's fundamental pattern is composition: we compose small units of code accomplishing very specific tasks into larger and complex units.

At a higher level the aim is modular programming:

By modular programming I mean the process of building large programs by gluing together smaller programs - Simon Peyton Jones

The term combinator refers to the combinator pattern:

A style of organizing libraries centered around the idea of combining things. Usually there is some type

T, some "primitive" values of typeT, and some "combinators" which can combine values of typeTin various ways to build up more complex values of typeT

The general form of a combinator is:

combinator: Thing -> ThingThe goal of a combinator is to create new things from things defined before.

Since this new Thing result can be passed around as input we obtain a combinatory explosion of opportunities, which makes this pattern extremely powerful.

If we mix several different combinators together we can obtain an even bigger combinatory explosion.

Thus the usual design you can find in a functional module is:

- a small set of "primitives"

- a set of combinators to combine the primitives in larger structures

Demo

Sometimes, the elegant implementation is just a function. Not a method. Not a class. Not a framework. Just a function. - John Carmack

Of the two combiners in 01_retry.ts a special mention goes to concat since it refers to a very powerful functional programming abstraction: semigroups.

A term we could associate to functional programming might be algebraic programming:

Algebras can be thought of as the design patterns for functional programming

An algebra is generally defined as whatever combination of:

- sets

- operations

- laws

Algebras are how mathematicians try to capture an idea in its purest form, eliminating everything that is superfluous.

Algebras can be thought of as an abstraction of interfaces: when an algebraic structure is modified we can only use the operations defined by the algebra, those allowed in compliance with its own laws.

Mathematicians work with such interfaces from centuries, and it works.

Let's see our first example of an algebra, a magma.

Definition. Given A a non empty set and * a binary operation closed on (or internal to) A, then the pair (A, *) is called a magma.

Note: An operation * is closed on A if *: A × A ⟶ A. This means that whichever elements of the set A we apply the operation on the result will still be an element of A.

integer + integer = integer

integer / integer = integer | float | NaNOn line 1 we have the pair (integer, +). The non empty set is the set of integers (in most cases the terms set and type can be used interchangeably), while the binary operation is the usual mathematical addition. No matter which integers we operate on, the sum will always result with an integer. Thus the pair (integer, +) is a magma.

On line 2 we have the pair (integer, /) where the binary operation is the usual division between integers. While this operation results in an integer in some cases (e.g. 9 / 3 = 3), it does not for all the members of the integer set (e.g. 1 / 0 or 10 / 3). Thus, division, is not closed on integer. Thus, the pair (integer, /) is not a magma.

Food for your thoughts: explain why the pair (positive, -), where positive is the set of positive numbers, such as (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc), does not form a magma under the binary operation -, the usual mathematical subtraction.

An interesting property of magmas:

Since the binary operation of a magma takes two values of a given type and returns a new value of the same type (closure property), this operation can be chained indefinitely.

And this is the encoding of a magma in TypeScript:

- the set is encoded in a type parameter (the generic

AinMagma<A>) - the

*operation is here calledconcat(theconcatmethod implemented in any instance ofMagma<A>)

// fp-ts/lib/Magma.ts

interface Magma<A> {

readonly concat: (x: A, y: A) => A

}Magmas do not obey any law, they only have the closure requirement. Let's see an algebra that do requires another law: semigroups.

Given (A, *) a magma, if * is associative then it's a semigroup.

The term "associative" means that the equation:

(x * y) * z = x * (y * z)holds for any x, y, z in A.

In layman terms associativity tells us that we do not have to need to worry about parentheses in expressions and that, we can simply write x * y * z (there's no ambiguity).

Example

String concatenation benefits from associativity.

("a" + "b") + "c" = "a" + ("b" + "c") = "abc"A characteristic of associativity is that:

Semigroups capture the essence of parallelizable operations

If we know that there is such an operation that follows the associativity law we can further split a computation in two sub computations, each of them could be further split in sub computations.

a * b * c * d * e * f * g * h = ((a * b) * (c * d)) * ((e * f) * (g * h))Sub computations can be run in parallel mode.

There are many examples of semigroups:

(number, +)where+is the usual addition of numbers(number, *)where*is the usual number multiplication(string, +)where+is the usual string concatenation(boolean, &&)where&&is the logical conjunction(boolean, ||)where||is the logical disjunction

As usual in fp-ts the algebra Semigroup, contained in the the fp-ts/lib/Semigroup module, is implemented through a TypeScript interface:

// fp-ts/lib/Semigroup.ts

interface Semigroup<A> extends Magma<A> {}The following law has to hold true:

- Associativity:

concat(concat(x, y), z) = concat(x, concat(y, z)), for everyx,y,zinA

Note. Sadly it is not possible to encode this law in TypeScript's type system.

The name concat makes sense for arrays (as we'll see later) but, depending on the context and the type A on whom we're implementing an instance, the concat semigroup operation may have different interpretations and meanings:

- "concatenation"

- "merging"

- "fusion"

- "selection"

- "addition"

- "substitution"

and many others.

Example

This is how to implement the semigroup (number, +) where + is the usual addition of numbers:

/** number `Semigroup` under addition */

const semigroupSum: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => x + y

}Please note that for the same type (the underlying non-empty set, in the previous case number) it is possible to define more instances of the type class Semigroup.

It is a common mistake to think about the semigroup of numbers, but remember that a semigroup is a pair (A,*) of a non-empty set and an associative operation. So when specifying a semigroup we need both a non-empty set (or type, such as number, string, or more complex ones) and an operation.

This is the implementation for the semigroup (number, *) where * is the usual number multiplication:

/** number `Semigroup` under multiplication */

const semigroupProduct: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => x * y

}Another example, with two strings this time:

const semigroupString: Semigroup<string> = {

concat: (x, y) => x + y

}By definition concat combines merely two elements of A every time, is it possible to combine any n number of them?

The fold function takes:

- an instance of a semigroup

- an initial value

- an array of elements

import {

fold,

semigroupSum,

semigroupProduct

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

const sum = fold(semigroupSum)

sum(0, [1, 2, 3, 4]) // 10

const product = fold(semigroupProduct)

product(1, [1, 2, 3, 4]) // 24Quiz. Why do I need to provide an initial value?

Example

Lets provide some applications of fold, by reimplementing some popular functions from the JavaScript standard library.

import { Predicate } from 'fp-ts/lib/function'

import {

fold,

Semigroup,

semigroupAll,

semigroupAny

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

function every<A>(p: Predicate<A>, as: Array<A>): boolean {

return fold(semigroupAll)(true, as.map(p))

}

function some<A>(p: Predicate<A>, as: Array<A>): boolean {

return fold(semigroupAny)(false, as.map(p))

}

const semigroupObject: Semigroup<object> = {

concat: (x, y) => ({ ...x, ...y })

}

function assign(as: Array<object>): object {

return fold(semigroupObject)({}, as)

}Given a Semigroup instance, it is possible to obtain a new Semigroup instance simply swapping the order in which the operands are combined:

// this is a Semigroup combinator

function getDualSemigroup<A>(

S: Semigroup<A>

): Semigroup<A> {

return {

concat: (x, y) => S.concat(y, x)

}

}Quiz. This combinator makes sense because, generally speaking, the concat operation is not commutative, can you find an example?

What happens if, given a specific type A we can't find an associative binary operation on A?

You can always define a semigroup instance for any instance for any given type using the following constructors:

// fp-ts/lib/Semigroup.ts

/** Always return the first argument */

function getFirstSemigroup<A = never>(): Semigroup<A> {

return {

concat: (x, y) => x

}

}

/** Always return the second argument */

function getLastSemigroup<A = never>(): Semigroup<A> {

return {

concat: (x, y) => y

}

}Quiz: Can you explain the presence of the = never for the type parameter A?

Another technique is to define a semigroup instance not for the A type but for Array<A> (to be precise, it is a semigroup instance not for A but for the non-empty arrays of A) called the free semigroup of A.

function getSemigroup<A = never>(): Semigroup<Array<A>> {

return {

concat: (x, y) => x.concat(y)

}

}and then we can map the elements of A to the singleton (a one-dimensional tuple) of Array<A> meaning an array with only one A element.

function of<A>(a: A): Array<A> {

return [a]

}Notes. The concat in getSemigroup is the native array concat operation, this also explains why concat is the name of *, the binary associative operation of semigroups.

The free semigroup of A thus is simply the semigroup whose elements are all the possible finite and non-empty combinations of A elements.

The free semigroup of A can be seen as a lazy way of concatenating elements of A while preserving the content of A.

Even though I may have an instance of a semigroup for A, I could very well decide to use the free semigroup nonetheless because:

- it avoids executing potentially useless computations

- it avoids passing around the semigroup instance

- allows the consumer of my APIs to decide the merging strategy

Let's try defining a semigroup instance for more complex types:

import {

Semigroup,

semigroupSum

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

type Point = {

x: number

y: number

}

const semigroupPoint: Semigroup<Point> = {

concat: (p1, p2) => ({

x: semigroupSum.concat(p1.x, p2.x),

y: semigroupSum.concat(p1.y, p2.y)

})

}Too much boilerplate? The good news is that we can construct a semigroup instance for a struct like Point if we are able to provide a semigroup instance for each of its fields.

Conveniently the fp-ts/lib/Semigroup module exports a getStructSemigroup instance:

import {

getStructSemigroup,

Semigroup,

semigroupSum

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

type Point = {

x: number

y: number

}

const semigroupPoint: Semigroup<Point> = getStructSemigroup(

{

x: semigroupSum,

y: semigroupSum

}

)We can keep passing to getStructSemigroup the freshly defined semigroupPoint instance.:

type Vector = {

from: Point

to: Point

}

const semigroupVector: Semigroup<

Vector

> = getStructSemigroup({

from: semigroupPoint,

to: semigroupPoint

})Note. There is a combinator similar to getStructSemigroup that works with tuples: getTupleSemigroup.

There are other combinators exported from fp-ts, here we can see a combinator that allows us to derive a semigroup instance for functions: given an instance of a semigroup B we can derive a new semigroup instance for functions with the following signatures: (a: A) => B (for every possible A).

Example

import { Predicate } from 'fp-ts/lib/function'

import {

getFunctionSemigroup,

semigroupAll

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

/** `semigroupAll` is the boolean semigroup under conjunction */

const semigroupPredicate: Semigroup<

Predicate<Point>

> = getFunctionSemigroup(semigroupAll)<Point>()Now we can "merge" two predicates defined over Point.

const isPositiveX = (p: Point): boolean => p.x >= 0

const isPositiveY = (p: Point): boolean => p.y >= 0

const isPositiveXY = semigroupPredicate.concat(

isPositiveX,

isPositiveY

)

isPositiveXY({ x: 1, y: 1 }) // true

isPositiveXY({ x: 1, y: -1 }) // false

isPositiveXY({ x: -1, y: 1 }) // false

isPositiveXY({ x: -1, y: -1 }) // falseGiven that number is a total order (meaning that whatever two x and y we choose, one of those two conditions has to hold true: x <= y or y <= x) we can define another two instances of semigroup using min or max as operations.

const meet: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => Math.min(x, y)

}

const join: Semigroup<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => Math.max(x, y)

}Quiz. Why is it so important that number is a total order?

Is it possible to capture the notion of being totally ordered for other types that are not number? To do so we first need to capture the notion of equality.

Equivalence relations capture the concept of equality of elements of the same type. The concept of an equivalence relation can be implemented in TypeScript with the following type class:

interface Eq<A> {

readonly equals: (x: A, y: A) => boolean

}Intuitively:

- if

equals(x, y) = truethenx = y - if

equals(x, y) = falsethenx ≠ y

Example

This is an instance of Eq for the number type:

import { Eq } from 'fp-ts/lib/Eq'

const eqNumber: Eq<number> = {

equals: (x, y) => x === y

}The following laws have to hold true:

- Reflexivity:

equals(x, x) === true, for everyxinA - Symmetry:

equals(x, y) === equals(y, x), for everyx,yinA - Transitivity: if

equals(x, y) === trueandequals(y, z) === true, thenequals(x, z) === true, for everyx,y,zinA

Example

A programmer can thus define a function elem (which indicates whether a value appears in an array) in the following way:

function elem<A>(

E: Eq<A>

): (a: A, as: Array<A>) => boolean {

return (a, as) => as.some(item => E.equals(item, a))

}

elem(eqNumber)(1, [1, 2, 3]) // true

elem(eqNumber)(4, [1, 2, 3]) // falseLet's define some instances of Eq for more complex types.

type Point = {

x: number

y: number

}

const eqPoint: Eq<Point> = {

equals: (p1, p2) => p1.x === p2.x && p1.y === p2.y

}We can also try to optimize equals by first testing whether there is a reference equality (see fromEquals in fp-ts).

const eqPoint: Eq<Point> = {

equals: (p1, p2) =>

p1 === p2 || (p1.x === p2.x && p1.y === p2.y)

}Too much boilerplate? The good news is that we can write an Eq instance for a struct like Point if we can provide an Eq instance for each of its fields.

Conveniently, the fp-ts/lib/Eq module exports a combinator getStructEq:

import { getStructEq } from 'fp-ts/lib/Eq'

const eqPoint: Eq<Point> = getStructEq({

x: eqNumber,

y: eqNumber

})We can keep passing the just defined eqPoint to getStructEq.

type Vector = {

from: Point

to: Point

}

const eqVector: Eq<Vector> = getStructEq({

from: eqPoint,

to: eqPoint

})Note. There is a combinator similar to getStructEq that works on tuples: getTupleEq.

There are other combinators exported by fp-ts, here we can see one that allows us to derive an Eq instance from an array:

import { getEq } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

const eqArrayOfPoints: Eq<Array<Point>> = getEq(eqPoint)At last, another combinator to create new Eq instances is contramap: given an Eq<A> instance and a function from B to A we can derive an instance Eq<B>

import { contramap, eqNumber } from 'fp-ts/lib/Eq'

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable'

type User = {

userId: number

name: string

}

/** two users are equal if their `userId` field is equal */

const eqUser = pipe(

eqNumber,

contramap((user: User) => user.userId)

)

eqUser.equals(

{ userId: 1, name: 'Giulio' },

{ userId: 1, name: 'Giulio Canti' }

) // true

eqUser.equals(

{ userId: 1, name: 'Giulio' },

{ userId: 2, name: 'Giulio' }

) // falseSpoiler. contramap is the fundamental function of contravariant functors.

Defining an Eq<A> instance is equivalent to defining a partition of A where two elements x, y of A are members of the same partition if and only if equals(x, y) = true.

Note. Every f: A ⟶ B function creates an Eq<A> instance defined by:

equals(x, y) = f(x) = f(y)for every x, y of A.

Spoiler. We'll see how this notion will come back useful in the demo: 03_shapes.ts

In the previous chapter regarding Eq we were dealing with the concept of equality. In this one we'll deal with the concept of ordering.

The concept of a total order relation can be implemented in TypeScript with the following type class:

import { Eq } from 'fp-ts/lib/Eq'

type Ordering = -1 | 0 | 1

interface Ord<A> extends Eq<A> {

readonly compare: (x: A, y: A) => Ordering

}Resulting in:

x < yif and only ifcompare(x, y) = -1x = yif and only ifcompare(x, y) = 0x > yif and only ifcompare(x, y) = 1

Thus we can say that x <= y holds true only if compare(x, y) <= 0.

Example

Here we can see an instance of Ord for the type number:

const ordNumber: Ord<number> = {

equals: (x, y) => x === y,

compare: (x, y) => (x < y ? -1 : x > y ? 1 : 0)

}The following laws have to hold true:

- Reflexivity:

compare(x, x) <= 0, for everyxinA - Antisymmetry: if

compare(x, y) <= 0andcompare(y, x) <= 0thenx = y, for everyx,yinA - Transitivity: if

compare(x, y) <= 0andcompare(y, z) <= 0thencompare(x, z) <= 0, for everyx,y,zinA

compare has also to be compatible with the equals operation from Eq:

compare(x, y) === 0 if and only if equals(x, y) === true, for every x, y in A

Nota. equals can be lawfully derived from compare in the following way:

equals: (x, y) => compare(x, y) === 0In fact the fp-ts/lib/Ord module exports a handy helper fromCompare which allows us to define an Ord instance simply by supplying the compare function:

import { fromCompare, Ord } from 'fp-ts/lib/Ord'

const ordNumber: Ord<number> = fromCompare((x, y) =>

x < y ? -1 : x > y ? 1 : 0

)Thus a programmer can define a min function in the following way:

function min<A>(O: Ord<A>): (x: A, y: A) => A {

return (x, y) => (O.compare(x, y) === 1 ? y : x)

}

min(ordNumber)(2, 1) // 1The order's totality (thus given any x e y, one of the following conditions holds true: x <= y oppure y <= x) may look obvious when speaking about numbers, but that's not always the case. Let's consider a more complex case:

type User = {

name: string

age: number

}How can we define an Ord<User>?

It always depends on the context, but it's always possible to order the users based on their age:

const byAge: Ord<User> = fromCompare((x, y) =>

ordNumber.compare(x.age, y.age)

)We can eliminate some boilerplate using the combinator contramap: given an Ord instance for A and a function from B to A, we can derive an instance of Ord for B

import { contramap } from 'fp-ts/lib/Ord'

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable'

const byAge: Ord<User> = pipe(

ordNumber,

contramap((user: User) => user.age)

)Spoiler. contramap is the fundamental function of contravariant functors.

Now we can obtain the youngest of two users using min:

const getYounger = min(byAge)

getYounger(

{ name: 'Guido', age: 48 },

{ name: 'Giulio', age: 45 }

) // { name: 'Giulio', age: 45 }And what if we wanted to obtain the eldest one? We can invert the order, or better, obtain the dual order.

Luckily there's an another combinator for this:

import { getDualOrd } from 'fp-ts/lib/Ord'

function max<A>(O: Ord<A>): (x: A, y: A) => A {

return min(getDualOrd(O))

}

const getOlder = max(byAge)

getOlder(

{ name: 'Guido', age: 48 },

{ name: 'Giulio', age: 45 }

) // { name: 'Guido', age: 48 }We've seen before that semigroups are helpful every time we want to "concat"enate or "merge" (choose the word that fits your intuition and use case better) different data in one.

There's another way of creating a semigroup instance for A: if we already have an Ord<A> then we can derive one of semigroup.

Actually we can derive two of them:

import { ordNumber } from 'fp-ts/lib/Ord'

import {

getJoinSemigroup,

getMeetSemigroup,

Semigroup

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

/** Takes the minimum of two values */

const semigroupMin: Semigroup<number> = getMeetSemigroup(

ordNumber

)

/** Takes the maximum of two values */

const semigroupMax: Semigroup<number> = getJoinSemigroup(

ordNumber

)

semigroupMin.concat(2, 1) // 1

semigroupMax.concat(2, 1) // 2Example

Let's wrap it up with one finale example (taken from Fantas, Eel, and Specification 4: Semigroup)

Let's suppose of building a system where a client's record are modelled in the following way:

interface Customer {

name: string

favouriteThings: Array<string>

registeredAt: number // since epoch

lastUpdatedAt: number // since epoch

hasMadePurchase: boolean

}For some reason you may end up having duplicate records for the same person.

We need a merging strategy and that's exactly what semigroups take care of!

import { getMonoid } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import { contramap, ordNumber } from 'fp-ts/lib/Ord'

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable'

import {

getJoinSemigroup,

getMeetSemigroup,

getStructSemigroup,

Semigroup,

semigroupAny

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

const semigroupCustomer: Semigroup<

Customer

> = getStructSemigroup({

// keep the longer name

name: getJoinSemigroup(

pipe(

ordNumber,

contramap((s: string) => s.length)

)

),

// accumulate things

favouriteThings: getMonoid<string>(),

// keep the least recent date

registeredAt: getMeetSemigroup(ordNumber),

// keep the most recent date

lastUpdatedAt: getJoinSemigroup(ordNumber),

// boolean semigroup under disjunction

hasMadePurchase: semigroupAny

})

semigroupCustomer.concat(

{

name: 'Giulio',

favouriteThings: ['math', 'climbing'],

registeredAt: new Date(2018, 1, 20).getTime(),

lastUpdatedAt: new Date(2018, 2, 18).getTime(),

hasMadePurchase: false

},

{

name: 'Giulio Canti',

favouriteThings: ['functional programming'],

registeredAt: new Date(2018, 1, 22).getTime(),

lastUpdatedAt: new Date(2018, 2, 9).getTime(),

hasMadePurchase: true

}

)

/*

{ name: 'Giulio Canti',

favouriteThings: [ 'math', 'climbing', 'functional programming' ],

registeredAt: 1519081200000, // new Date(2018, 1, 20).getTime()

lastUpdatedAt: 1521327600000, // new Date(2018, 2, 18).getTime()

hasMadePurchase: true }

*/Demo

If we add another condition to the definition of a semigroup (A, *), such as exists an element u in A such as for every element a in A holds true the following condition:

u * a = a * u = athen the triplet (A, *, u) is called a monoid and the element u is called unity.

(synonyms: neutral element, identity element).

import { Semigroup } from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

interface Monoid<A> extends Semigroup<A> {

readonly empty: A

}The following laws have to hold true:

- Right identity:

concat(a, empty) = a, for everyainA - Left identity:

concat(empty, a) = a, for everyainA

Note. The monoids unity is unique.

Many of the semigroups we've seen before are monoids as well:

/** number `Monoid` under addition */

const monoidSum: Monoid<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => x + y,

empty: 0

}

/** number `Monoid` under multiplication */

const monoidProduct: Monoid<number> = {

concat: (x, y) => x * y,

empty: 1

}

const monoidString: Monoid<string> = {

concat: (x, y) => x + y,

empty: ''

}

/** boolean monoid under conjunction */

const monoidAll: Monoid<boolean> = {

concat: (x, y) => x && y,

empty: true

}

/** boolean monoid under disjunction */

const monoidAny: Monoid<boolean> = {

concat: (x, y) => x || y,

empty: false

}Let's see some more complex example.

Given a type A, the endomorphisms (an endomorphism is simply a function whose domain and codomain are the same) on A admit a monoid instance:

type Endomorphism<A> = (a: A) => A

function identity<A>(a: A): A {

return a

}

function getEndomorphismMonoid<A = never>(): Monoid<

Endomorphism<A>

> {

return {

concat: (x, y) => a => x(y(a)),

empty: identity

}

}If the type M admits a monoid instance then the type (a: A) => M gives rise to a monoid instance for every type A:

function getFunctionMonoid<M>(

M: Monoid<M>

): <A = never>() => Monoid<(a: A) => M> {

return () => ({

concat: (f, g) => a => M.concat(f(a), g(a)),

empty: () => M.empty

})

}As a consequence we can see that reducers admit a monoid instance:

type Reducer<S, A> = (a: A) => (s: S) => S

function getReducerMonoid<S, A>(): Monoid<Reducer<S, A>> {

return getFunctionMonoid(getEndomorphismMonoid<S>())<A>()

}One could think that every semigroup is also a monoid. That's not the case. Let's see a counter example:

const semigroupSpace: Semigroup<string> = {

concat: (x, y) => x + ' ' + y

}It is not possible to find such an empty value that concat(x, empty) = x.

Lastly we can construct a monoid instance for a structure like Point:

type Point = {

x: number

y: number

}if we are able to feed the getStructMonoid a monoid instance for each of its fields:

import {

getStructMonoid,

Monoid,

monoidSum

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Monoid'

const monoidPoint: Monoid<Point> = getStructMonoid({

x: monoidSum,

y: monoidSum

})We can move further through the freshly defined getStructMonoid instance:

type Vector = {

from: Point

to: Point

}

const monoidVector: Monoid<Vector> = getStructMonoid({

from: monoidPoint,

to: monoidPoint

})Note. There is a combinator similar to getStructMonoid that works with tuples: getTupleMonoid.

When we use a monoid instead of a semigroup the folding operation is even easier: we no longer need to feed an initial value, we can use the neutral element for that:

import {

fold,

monoidAll,

monoidAny,

monoidProduct,

monoidString,

monoidSum

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Monoid'

fold(monoidSum)([1, 2, 3, 4]) // 10

fold(monoidProduct)([1, 2, 3, 4]) // 24

fold(monoidString)(['a', 'b', 'c']) // 'abc'

fold(monoidAll)([true, false, true]) // false

fold(monoidAny)([true, false, true]) // trueDemo

A pure function is a procedure that given the same input always gives the same output and does not have any observable side effect.

Such an informal statement could leave space for some doubts

- what is a "side effect"?

- what does it means "observable"?

- what does it mean "same"?

Let's see a formal definition of the concept of a function.

Note. If X e Y are sets, then with X × Y we indicate their cartesian product, meaning the set

X × Y = { (x, y) | x ∈ X, y ∈ Y }

The following definition was given a century ago:

Definition. A _function: f: X ⟶ Y is a subset of X × Y such as

for every x ∈ X there's exactly one y ∈ Y such that (x, y) ∈ f.

The set X is called domain of f, Y it's his codomain.

Example

The function double: Nat ⟶ Nat is the subset of the cartesian product Nat × Nat given by { (1, 2), (2, 4), (3, 6), ...}.

In TypeScript

const f: { [key: number]: number } = {

1: 2,

2: 4,

3: 6

...

}Please note that the set f has to be described statically when defining the function (meaning that the elements of that set cannot change with time for no reason).

In this way we can exclude any form of side effect and the return value is always the same.

The one in the example is called an extensional definition of a function, meaning we enumerate one by one each of the elements of its domain. Obviously, when such a set is infinite this proves to be problematic.

We can get around this issue by introducing the one that is called intentional definition, meaning that we express a condition that has to hold for every couple (x, y) ∈ f meaning y = x * 2.

This the familiar form in which we write the double function and its definition in TypeScript:

function double(x: number): number {

return x * 2

}The definition of a function as a subset of a cartesian product shows how in mathematics every function is pure: there is no action, no state mutation or elements being modified. In functional programming the implementation of functions has to follow as much as possible this ideal model.

The fact that a function is pure does not imply automatically a ban on local mutability as long as it doesn't leaks out of its scope.

The ultimate goal is to guarantee: referential transparency.

An expression contains "side effects" if it doesn't benefits from referential transparency

Functions compose:

Definition. Given f: Y ⟶ Z and g: X ⟶ Y two functions, then the function h: X ⟶ Z defined by:

h(x) = f(g(x))

is called composition of f and g and is written h = f ∘ g

Please note that in order for f and g to combine, the domain of f has to be included in the codomain of g.

Definition. A function is said to be partial if it is not defined for each value of its domain.

Vice versa, a function defined for all values of its domain is said to be total

Example

f(x) = 1 / x

The function f: number ⟶ number is not defined for x = 0.

A partial function f: X ⟶ Y can always be "brought back" to a total one by adding a special value, let's call it None, to the codomain and by assigning it to the output of f for every value of X where the function is not defined.

f': X ⟶ Y ∪ None

Let's call it Option(Y) = Y ∪ None.

f': X ⟶ Option(Y)

In functional programming the tendency is to define only pure and and total functions.

Is it possible to define Option in TypeScript?

A good first step when writing an application or feature is to define it's domain model. TypeScript offers many tools that help accomplishing this task. Algebraic Data Types (in short, ADTs) are one of these tools.

In computer programming, especially functional programming and type theory, an algebraic data type is a kind of composite type, i.e., a type formed by combining other types.

Two common families of algebraic data types are:

- product types

- sum types

Let's begin with the more familiar ones: product types.

A product type is a collection of types Ti indexed by a set I.

Two members of this family are n-tuples, where I is an interval of natural numbers:

type Tuple1 = [string] // I = [0]

type Tuple2 = [string, number] // I = [0, 1]

type Tuple3 = [string, number, boolean] // I = [0, 1, 2]

// Accessing by index

type Fst = Tuple2[0] // string

type Snd = Tuple2[1] // numberand structs, where I is a set of labels:

// I = {"name", "age"}

interface Person {

name: string

age: number

}

// Accessing by label

type Name = Person['name'] // string

type Age = Person['age'] // numberIf we label with C(A) the number of elements of type A (also called in mathematics, cardinality), then the following identities hold true:

C([A, B]) = C(A) * C(B)the cardinality of a product is the product of the cardinalities

Example

type Hour = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

type Period = 'AM' | 'PM'

type Clock = [Hour, Period]Type Clock has 12 * 2 = 24 elements.

Each time it's components are independent.

type Clock = [Hour, Period]Here Hour and Period are independent: the value of Hour does not change the value of Period. Every legal pair of [Hour, Period] makes "sense" and is legal.

A sum type is a a data type that can hold a value of different (but limited) types. Only one of these types can be used in a single instance and there is generally a "tag" value differentiating those types.

In TypeScript official docs those are called tagged union types.

Example (redux actions)

type Action =

| {

type: 'ADD_TODO'

text: string

}

| {

type: 'UPDATE_TODO'

id: number

text: string

completed: boolean

}

| {

type: 'DELETE_TODO'

id: number

}The type tag makes sure every member of the union is disjointed.

Note. The name of the field that acts as a tag is chosen by the developer. It doesn't have to be "type".

A sum type with n elements needs at least n constructors, one for each member:

const add = (text: string): Action => ({

type: 'ADD_TODO',

text

})

const update = (

id: number,

text: string,

completed: boolean

): Action => ({

type: 'UPDATE_TODO',

id,

text,

completed

})

const del = (id: number): Action => ({

type: 'DELETE_TODO',

id

})Sum types can be polymorphic and recursive.

Example (linked lists)

// ↓ type parameter

type List<A> =

| { type: 'Nil' }

| { type: 'Cons'; head: A; tail: List<A> }

// ↑ recursionJavaScript doesn't have pattern matching (neither does TypeScript) but we can simulate it with a fold function:

const fold = <A, R>(

onNil: () => R,

onCons: (head: A, tail: List<A>) => R

) => (fa: List<A>): R =>

fa.type === 'Nil' ? onNil() : onCons(fa.head, fa.tail)Note. TypeScript offers a great feature for sum types: exhaustive check. The type checker is able to infer if all the cases are covered.

Example (calculate the length of a List recursively)

const length: <A>(fa: List<A>) => number = fold(

() => 0,

(_, tail) => 1 + length(tail)

)Because the following identity holds true:

C(A | B) = C(A) + C(B)The sum of the cardinality is the sum of the cardinalities

Example (the Option type)

type Option<A> =

| { _tag: 'None' }

| {

_tag: 'Some'

value: A

}From the general formula C(Option<A>) = 1 + C(A) we can derive the cardinality of the Option<boolean> type: 1 + 2 = 3 abitanti.

When the components would be dependent if implemented with a product type.

Example (component props)

interface Props {

editable: boolean

onChange?: (text: string) => void

}

class Textbox extends React.Component<Props> {

render() {

if (this.props.editable) {

// error: Cannot invoke an object which is possibly 'undefined' :(

this.props.onChange(...)

}

}

}The problem here is that Props is modelled like a product but onChange depends on editable.

A sum type is a better choice:

type Props =

| {

type: 'READONLY'

}

| {

type: 'EDITABLE'

onChange: (text: string) => void

}

class Textbox extends React.Component<Props> {

render() {

switch (this.props.type) {

case 'EDITABLE' :

this.props.onChange(...) // :)

...

}

}

}Example (node callbacks)

declare function readFile(

path: string,

// ↓ ---------- ↓ CallbackArgs

callback: (err?: Error, data?: string) => void

): voidThe result is modelled with a product type:

type CallbackArgs = [Error | undefined, string | undefined]there's an issue though: it's components are dependent: we either receive an error or a string, but not both: but the components are

| err | data | legal? |

|---|---|---|

Error |

undefined |

✓ |

undefined |

string |

✓ |

Error |

string |

✘ |

undefined |

undefined |

✘ |

A sum type would be a better choice...but which sum type?

Let's see how to handle errors in a functional way.

The type Option represents the effect of a computation which may fail or return a type A:

type Option<A> =

| { _tag: 'None' } // represents a failure

| { _tag: 'Some'; value: A } // represents a successConstructors and pattern matching:

// a nullary constructor can be implemented as a constant

const none: Option<never> = { _tag: 'None' }

const some = <A>(value: A): Option<A> => ({

_tag: 'Some',

value

})

const fold = <A, R>(

onNone: () => R,

onSome: (a: A) => R

) => (fa: Option<A>): R =>

fa._tag === 'None' ? onNone() : onSome(fa.value)The Option type can be used to avoid throwing exceptions or representing the optional values, thus we can move from...

// this is a lie ↓

function head<A>(as: Array<A>): A {

if (as.length === 0) {

throw new Error('Empty array')

}

return as[0]

}

let s: string

try {

s = String(head([]))

} catch (e) {

s = e.message

}...where the type systems is in the absolute dark about the possibility of a failure, to...

// ↓ the type system "knows" that this computation may fail

function head<A>(as: Array<A>): Option<A> {

return as.length === 0 ? none : some(as[0])

}

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable'

const s = pipe(

head([]),

fold(() => 'Empty array', a => String(a))

)...where the possibility of an error is encoded in the type system.

Now, let's suppose we want to "merge" two different Option<A>s,: there are four different cases:

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a) | none | none |

| none | some(a) | none |

| some(a) | some(b) | ? |

There's an issue in the last case, we need to "merge" two different As.

Isn't that the job our old good friends Semigroups!? We can request an instance of a Semigroup<A> and then derive an instance for the semigroup of Option<A>. That's exactly how the combinator getApplySemigroup from fp-ts works:

import { semigroupSum } from 'fp-ts/lib/Semigroup'

import {

getApplySemigroup,

some,

none

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const S = getApplySemigroup(semigroupSum)

S.concat(some(1), none) // none

S.concat(some(1), some(2)) // some(3)If we have a monoid instance for A then we can derive a monoid instance for Option<A> (via getApplyMonoid) that works this way (some(empty) will be the neutral (identity) element):

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a) | none | none |

| none | some(a) | none |

| some(a) | some(b) | some(concat(a, b)) |

import {

getApplyMonoid,

some,

none

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const M = getApplyMonoid(monoidSum)

M.concat(some(1), none) // none

M.concat(some(1), some(2)) // some(3)

M.concat(some(1), M.empty) // some(1)We can derive another two monoids for Option<A> (for every A):

getFirstMonoid...

Monoid returning the left-most non-None value:

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a) | none | some(a) |

| none | some(a) | some(a) |

| some(a) | some(b) | some(a) |

import {

getFirstMonoid,

some,

none

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const M = getFirstMonoid<number>()

M.concat(some(1), none) // some(1)

M.concat(some(1), some(2)) // some(1)- ...and it's dual:

getLastMonoid

Monoid returning the right-most non-None value:

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a) | none | some(a) |

| none | some(a) | some(a) |

| some(a) | some(b) | some(b) |

import { getLastMonoid, some, none } from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const M = getLastMonoid<number>()

M.concat(some(1), none) // some(1)

M.concat(some(1), some(2)) // some(2)Example given, getLastMonoid can be used to handle optional values:

import { Monoid, getStructMonoid } from 'fp-ts/lib/Monoid'

import {

Option,

some,

none,

getLastMonoid

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

/** VSCode settings */

interface Settings {

/** Controls the font family */

fontFamily: Option<string>

/** Controls the font size in pixels */

fontSize: Option<number>

/** Limit the width of the minimap to render at most a certain number of columns. */

maxColumn: Option<number>

}

const monoidSettings: Monoid<Settings> = getStructMonoid({

fontFamily: getLastMonoid<string>(),

fontSize: getLastMonoid<number>(),

maxColumn: getLastMonoid<number>()

})

const workspaceSettings: Settings = {

fontFamily: some('Courier'),

fontSize: none,

maxColumn: some(80)

}

const userSettings: Settings = {

fontFamily: some('Fira Code'),

fontSize: some(12),

maxColumn: none

}

/** userSettings overrides workspaceSettings */

monoidSettings.concat(workspaceSettings, userSettings)

/*

{ fontFamily: some("Fira Code"),

fontSize: some(12),

maxColumn: some(80) }

*/A common usage of Either is as an alternative for Option for handling the possibility of missing values.

In such use case, None is replaced by Left which holds the useful information. Right replaces Some. As a convention Left is used for failure while Right is used for success.

type Either<E, A> =

| { _tag: 'Left'; left: E } // represents a failure

| { _tag: 'Right'; right: A } // represents a successConstructors and pattern matching:

const left = <E, A>(left: E): Either<E, A> => ({

_tag: 'Left',

left

})

const right = <E, A>(right: A): Either<E, A> => ({

_tag: 'Right',

right

})

const fold = <E, A, R>(

onLeft: (left: E) => R,

onRight: (right: A) => R

) => (fa: Either<E, A>): R =>

fa._tag === 'Left' ? onLeft(fa.left) : onRight(fa.right)Let's get back to the callback example:

declare function readFile(

path: string,

callback: (err?: Error, data?: string) => void

): void

readFile('./myfile', (err, data) => {

let message: string

if (err !== undefined) {

message = `Error: ${err.message}`

} else if (data !== undefined) {

message = `Data: ${data.trim()}`

} else {

// should never happen

message = 'The impossible happened'

}

console.log(message)

})we can change the signature in:

declare function readFile(

path: string,

callback: (result: Either<Error, string>) => void

): voidand consume the API in this new way:

import { flow } from 'fp-ts/lib/function'

readFile(

'./myfile',

flow(

fold(

err => `Error: ${err.message}`,

data => `Data: ${data.trim()}`

),

console.log

)

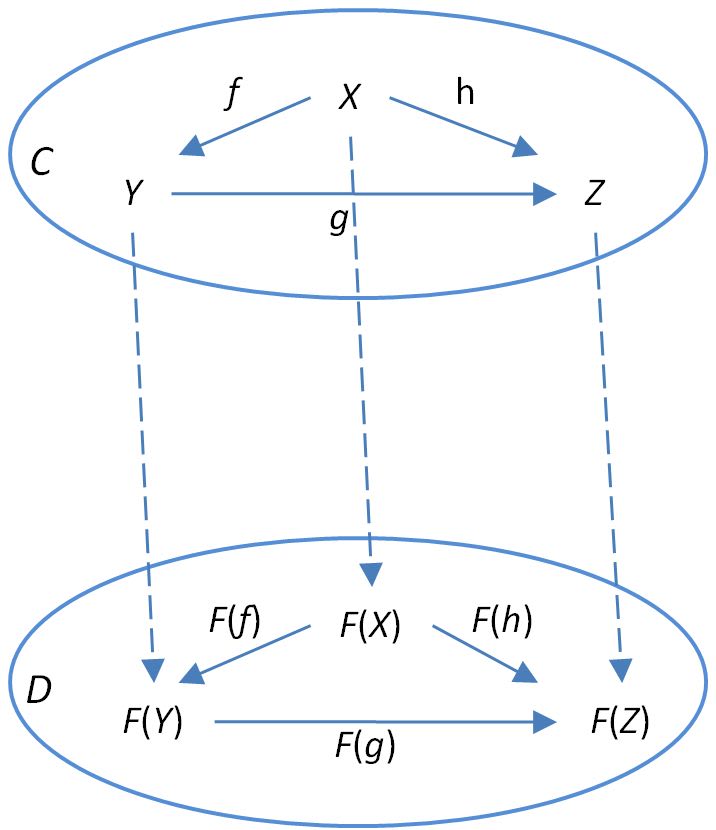

)Historically, the first advanced abstraction implemented in fp-ts has been Functor, but before we can talk about functors, we'll talk a bit about categories since functors are based on them.

One of functional's programming core characteristics is composition

And how do we solve problems? We decompose bigger problems into smaller problems. If the smaller problems are still too big, we decompose them further, and so on. Finally, we write code that solves all the small problems. And then comes the essence of programming: we compose those pieces of code to create solutions to larger problems. Decomposition wouldn't make sense if we weren't able to put the pieces back together. - Bartosz Milewski

But what does it means exactly? How can we say two things compose? And how can we say two things compose well?

Entities are composable if we can easily and generally combine their behaviours in some way without having to modify the entities being combined. I think of composability as being the key ingredient necessary for achieving reuse, and for achieving a combinatorial expansion of what is succinctly expressible in a programming model. - Paul Chiusano

We need to refer to a strict theory able to answer such fundamental questions. We need a formal definition of the concept of composability.

Luckily, for the last 60 years ago, a large number of researchers, members of the oldest and largest humanity's open source project (maths) occupies itself with developing a theory dedicated to composability: category theory.

Categories capture the essence of composition.

Saunders Mac Lane

Samuel Eilenberg

The definition of a category, even though isn't really complex, is a bit long, thus I'll split it in two parts:

- the first is merely technical (we need to define its laws)

- the second one will be more relevant to what we care for: a notion of composition

A category is an (Objects, Morphisms) pair where:

Objectsis a collection of objectsMorphismsis a collection of morphisms (also called "arrows") between objects

Note. The term "object" has nothing to do with the concept of "objects" in programming and. Just think about those "objects" as black boxes we can't inspect, or simple placeholders useful to define the various morphisms.

Every morphism f owns a source object A and a target object B.

In every morphism, both A and B are members of Objects. We write f: A ⟼ B and we say that"f is a morphism from A to B"

There is an operation, ∘, called "composition", such as the following properties hold true:

- (composition of morphisms) every time we have two morphisms

f: A ⟼ Bandg: B ⟼ CinMorphismsthen there has to be a thirdg ∘ f: A ⟼ CinMorphismswhich is the composition offandg - (associativity) if

f: A ⟼ B,g: B ⟼ Candh: C ⟼ Dthenh ∘ (g ∘ f) = (h ∘ g) ∘ f - (identity) for every object

X, there is a morphismidentity: X ⟼ Xcalled identity morphism ofX, such as for every morphismf: A ⟼ Xandg: X ⟼ B, the following equation holds trueidentity ∘ f = fandg ∘ identity = g.

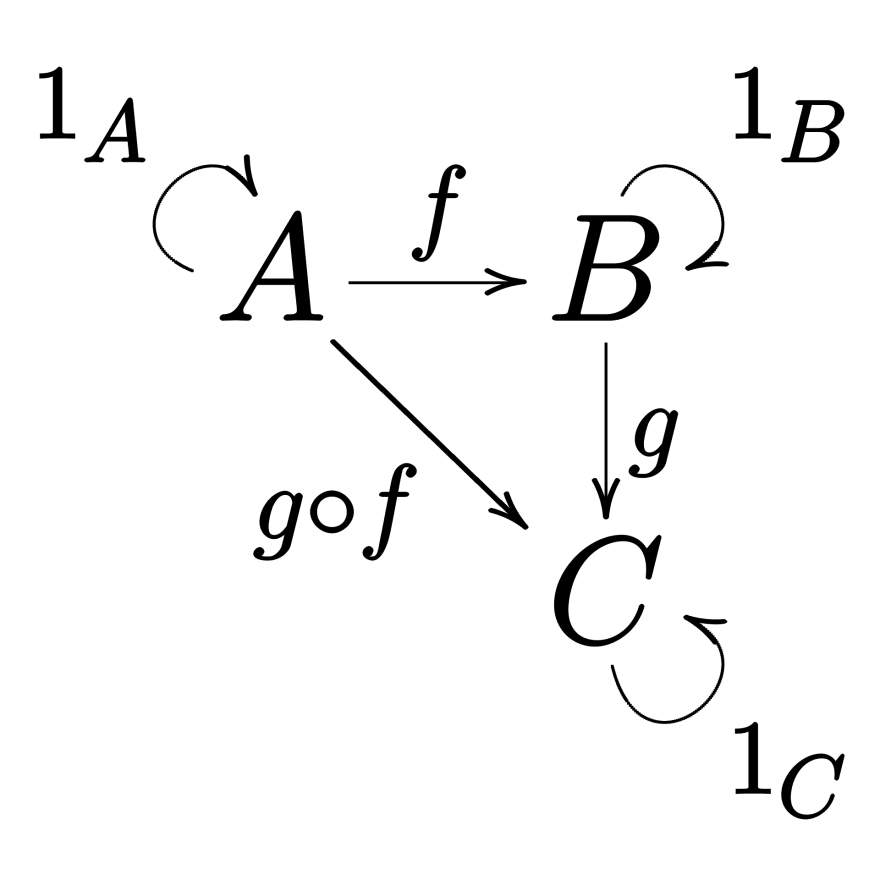

Example

(source: category on wikipedia.org)

This category is simple, there are three objects and six morphisms (1A, 1B, 1C are the identity morphisms for A, B, C).

A category can be seen as a simplified model for a typed programming language, where:

- the objects are types

- morphisms are functions

∘is the usual function composition

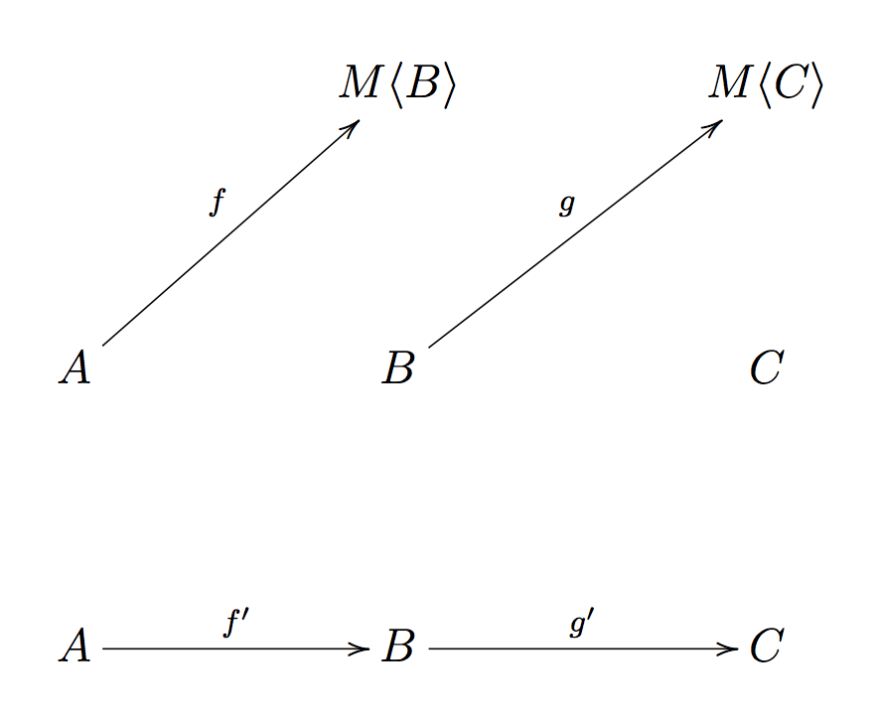

The following diagram:

can be seen as an imaginary (and simple) programming language with just three types and a handful of functions

Example given:

A = stringB = numberC = booleanf = string => numberg = number => booleang ∘ f = string => boolean

The implementation could be something like:

function f(s: string): number {

return s.length

}

function g(n: number): boolean {

return n > 2

}

// h = g ∘ f

function h(s: string): boolean {

return g(f(s))

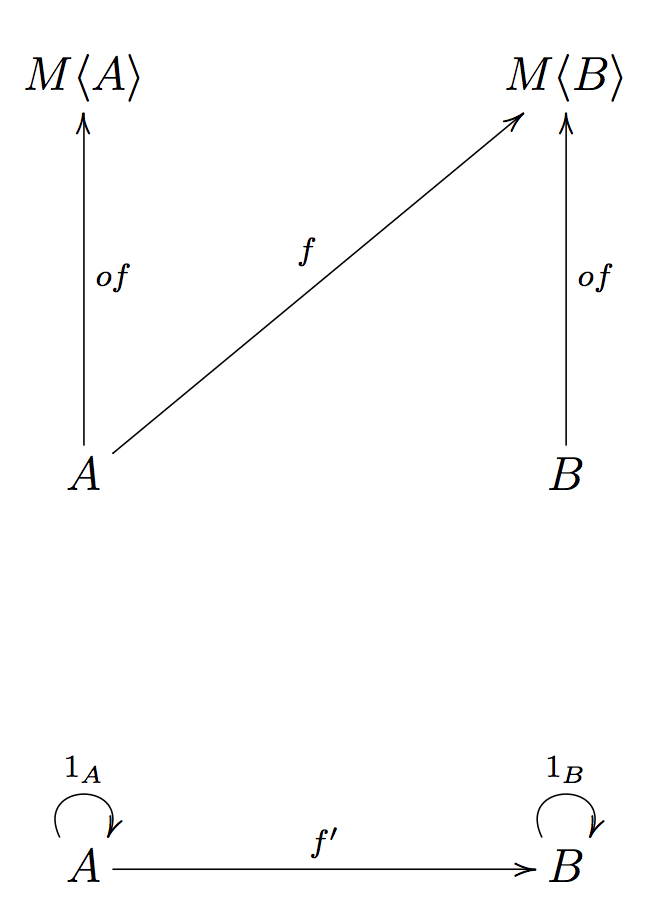

}We can define a category, let's call it TS, as a simplified model of the TypeScript language, where:

- the objects are all the possible TypeScript types:

string,number,Array<string>, ... - the morphisms are all TypeScript functions:

(a: A) => B,(b: B) => C, ... whereA,B,C, ... are TypeScript types - the identity morphisms are all encoded in a single polymorphic function

const identity = <A>(a: A): A => a - morphism's composition is the usual function composition (which we know to be associative)

As a model of TypeScript, the TS category may seem a bit limited: no loops, no ifs, there's almost nothing... that being said that simplified model is rich enough to help us reach our goal: to reason about a well-defined notion of composition.

In the TS category we can compose two generic functions f: (a: A) => B and g: (c: C) => D as long as C = B

function compose<A, B, C>(

g: (b: B) => C,

f: (a: A) => B

): (a: A) => C {

return a => g(f(a))

}But what happens if B != C? How can we compose two such functions? Should we give up?

In the next section we'll see under which conditions such a composition is possible. We'll talk about functors.

In the last section we've spoken about the TS category (the TypeScript category) and composition's core problem with functions:

How can we compose two generic functions

f: (a: A) => Beg: (c: C) => D?

Why is finding solutions to these problem so important?

Because, if it is true that categories can be used to model programming languages, morphisms (functions in the TS category) can be used to model programs.

Thus, solving this abstract problem means finding a concrete way of composing programs in a generic way. And that now is really interesting for us developers, isn't it?

How is it possible to model a program that produces side effects with a pure function?

The answer is to model it's side effects through effects, meaning types that represent side effects.

Let's see two possible techniques to do so in JavaScript:

- define a DSL (domain specific language) for effects

- use a thunk

The first technique, using a DSL, means modifying a program like:

function log(message: string): void {

console.log(message) // side effect

}changing its codomain and making possible that it'll be a function that returns a description of the side effect:

type DSL = ... // sum type of every possible effect handled by the system

function log(message: string): DSL {

return {

type: "log",

message

}

}Quiz. Is the freshly defined log function really pure? Actually log('foo') !== log('foo')!

This technique requires a way to combine effects and the definition of an interpreter able to execute the side effects.

The second technique is to enclose the computation in a thunk:

interface IO<A> {

(): A

}

function log(message: string): IO<void> {

return () => {

console.log(message)

}

}The log program, once executed, it won't instantly cause a side effect, but returns a value representing the computation (also known as action).

Let's see another example using thunks, reading and writing on localStorage:

const read = (name: string): IO<string | null> => () =>

localStorage.getItem(name)

const write = (

name: string,

value: string

): IO<void> => () => localStorage.setItem(name, value)In functional programming there's a tendency to shove side effects (under the form of effects) to the border of the system (the main function) where they are executed by an interpreter obtaining the following schema:

system = pure core + imperative shell

In purely functional languages (like Haskell, PureScript or Elm) this division is strict and clear and imposed by the very languages.

Even with this thunk technique (the same technique used in fp-ts) we need a way to combine effects, let's see how.

We first need a bit of terminology: we'll call pure program a function with the following signature:

(a: A) => BSuch a signature models a program that takes an input of type A and returns a result of type B without any effect.

Example

The len program:

const len = (s: string): number => s.lengthWe'll call an effectful program a function with the following signature:

(a: A) => F<B>Such a signature models a program that takes an input of type A and returns a result of type B together with an effect F, where F is some sort of type constructor.

Let's recall that a type constructor is an n-ary type operator that takes as argument one or more types and returns another type.

Example

The head program:

const head = (as: Array<string>): Option<string> =>

as.length === 0 ? none : some(as[0])is a program with an Option effect.

When we talk about effects we are interested in n-ary type constructors where n >= 1, example given:

| Type constructor | Effect (interpretation) |

|---|---|

Array<A> |

a non deterministic computation |

Option<A> |

a computation that may fail |

IO<A> |

a synchronous computation with side effects |

Task<A> |

an asynchronous computation |

where

interface Task<A> extends IO<Promise<A>> {}Let's get back to our core problem:

How do we compose two generic functions

f: (a: A) => Beg: (c: C) => D?

With our current set of rules this general problem is not solvable. We need to add some boundaries to B and C.

We already know that if B = C then the solution is the usual function composition.

function compose<A, B, C>(

g: (b: B) => C,

f: (a: A) => B

): (a: A) => C {

return a => g(f(a))

}But what about other cases?

Let's consider the following boundary: B = F<C> for some type constructor F, or in other words (and after some renaming):

f: (a: A) => F<B>is an effectful programg: (b: B) => Cis a pure program

In order to compose f with g we need to find a procedure (called lifting) that allows us to derive a function g from a function (b: B) => C to a function (fb: F<B>) => F<C> in order to use the usual function composition (in fact, in this way the codomain of f would be the same of the new function's domain).

That is, we have modified the original problem in a different and new one: can we find a lift function that operates this way?

Let's see some practical example:

Example (F = Array)

function lift<B, C>(

g: (b: B) => C

): (fb: Array<B>) => Array<C> {

return fb => fb.map(g)

}Example (F = Option)

import {

isNone,

none,

Option,

some

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

function lift<B, C>(

g: (b: B) => C

): (fb: Option<B>) => Option<C> {

return fb => (isNone(fb) ? none : some(g(fb.value)))

}Example (F = Task)

import { Task } from 'fp-ts/lib/Task'

function lift<B, C>(

g: (b: B) => C

): (fb: Task<B>) => Task<C> {

return fb => () => fb().then(g)

}All of these lift functions look pretty much similar. That's no coincidence, there's a very important pattern behind the scenes: every of these type constructors (and many others) admit an functor instance.

Functors are maps between categories that preserve the structure of the category, meaning they preserve the identity morphisms and the composition operation.

Since categories are pairs of objects and morphisms, a functor too is a pair of something:

- a map between objects that binds every object

Ain C an object in D. - a map between morphisms that binds every morphism in C a morphism in D.

where C e D are two categories (aka two programming languages).

(source: functor on ncatlab.org)

Even though a map between two different programming languages is an interesting idea, we're more interested in a map where C and D are the same (the TS category). In that case we're talking about endofunctors (from the greek "endo" meaning "inside"/"internal").

From now on, unless specified differently, when I write "functor" I mean an endofunctor in the TS category.

Now we know the practical side of functors, let's see the formal definition.

A functor is a pair (F, lift) where:

Fis ann-ary (n >= 1) type constructor mapping every typeXin a typeF<X>(map between objects)liftis a function with the following signature:

lift: <A, B>(f: (a: A) => B) => ((fa: F<A>) => F<B>)that maps every function f: (a: A) => B in a function lift(f): (fa: F<A>) => F<B> (map between morphism)

The following properties have to hold true:

lift(1X)=1F(X) (identities go to identities)lift(g ∘ f) = lift(g) ∘ lift(f)(the image of a composition is the composition of its images)

The lift function is also called under its variant map, which is essentially a lift with the argument's order rearranged:

lift: <A, B>(f: (a: A) => B) => ((fa: F<A>) => F<B>)

map: <A, B>(fa: F<A>, f: (a: A) => B) => F<B>Please note that map can be derived from lift (and vice versa).

How do we define a functor instance in fp-ts? Let's see some example:

The following interface represents the model of a call to some API:

interface Response<A> {

url: string

status: number

headers: Record<string, string>

body: A

}Please note that since body is parametric, this makes Response a good candidate to find a functor instance since Response is a an n-ary type constructor with n >= 1 (a necessary condition).

To define a functor instance for Response we need to define a map function along some technical details required by fp-ts.

// `Response.ts` module

import { Functor1 } from 'fp-ts/lib/Functor'

export const URI = 'Response'

export type URI = typeof URI

declare module 'fp-ts/lib/HKT' {

interface URItoKind<A> {

Response: Response<A>

}

}

export interface Response<A> {

url: string

status: number

headers: Record<string, string>

body: A

}

function map<A, B>(

fa: Response<A>,

f: (a: A) => B

): Response<B> {

return { ...fa, body: f(fa.body) }

}

// functor instance for `Response`

export const functorResponse: Functor1<URI> = {

URI,

map

}Functor compose, given two functors F e G, then the composition F<G<A>> is still a functor and its map is the combination of F's an G's map, thus the composition

Example

import { Option, option } from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

import { array } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

export const functorArrayOption = {

map: <A, B>(

fa: Array<Option<A>>,

f: (a: A) => B

): Array<Option<B>> =>

array.map(fa, oa => option.map(oa, f))

}To avoid boilerplate fp-ts exports an helper:

import { array } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import { getFunctorComposition } from 'fp-ts/lib/Functor'

import { option } from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

export const functorArrayOption = getFunctorComposition(

array,

option

)Not yet. Functors allow us to compose an effectful program f with a pure program g, but g has to be a unary function, accepting one single argument. What happens if g takes two or more arguments?

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure (unary) | lift(g) ∘ f |

| effectful | pure (n-ary, n > 1) |

? |

To manage this circumstance we need something more, in the next chapter we'll see another important abstraction in functional programming: applicative functors.

Before we get into applicative functors I'd like to show you a variant of the functor concept we've seen in the last section: contravariant functors.

If we want to be meticulous, those that we called "functors" should be more properly called convariant functors.

The definition of a contravariant functor is very close to the covariant functor, the only difference is the signature of its fundamental operation (called contramap insteaf of map).

// covariant functor

export interface Functor<F> {

readonly map: <A, B>(

fa: HKT<F, A>,

f: (a: A) => B

) => HKT<F, B>

}

// contravariant functor

export interface Contravariant<F> {

readonly contramap: <A, B>(

fa: HKT<F, A>,

f: (b: B) => A

) => HKT<F, B>

}Note: the HKT type is the way fp-ts uses to represent a generic type constructor (a technique proposed in the following paper Lightweight higher-kinded polymorphism) so when you see HKT<F, X> you can simply read it as F applied on the X type (thus F<X>).

As examples, we've already seen two relevant types that admit an instance of a contravariant functor: Eq and Ord.

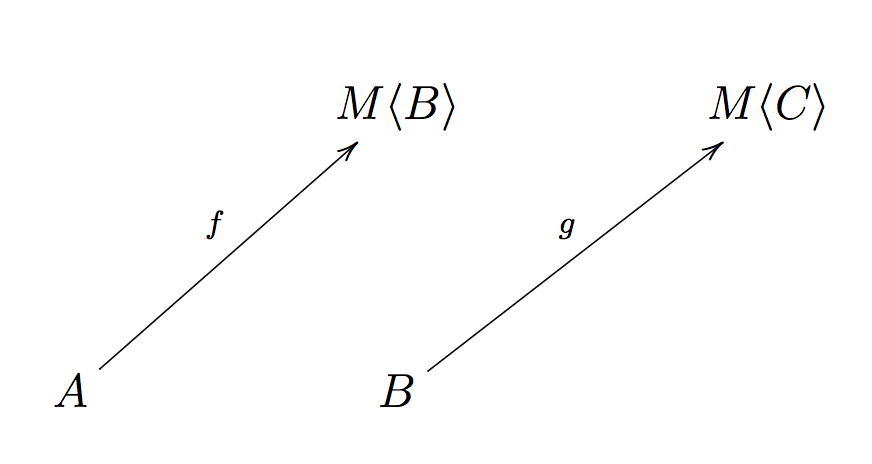

In the section regarding functors we've seen that we can compose an effectful program f: (a: A) => F<B> with a pure one g: (b: B) => C through the lifting of g to a function lift(g): (fb: F<B>) => F<C> (if and only if F has a functor instance).

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure (unary) | lift(g) ∘ f |

But g has to be unary, it can only accept a single argument as input. What happens if g accepts two arguments? Can we still lift g using only the functor instance? Let's try

First of all we need to model a function that accepts two arguments of type B e C (we can use a tuple for this) and returns a value of type D:

g: (args: [B, C]) => DWe can rewrite g using a technique called currying.

Currying is the technique of translating the evaluation of a function that takes multiple arguments into evaluating a sequence of functions, each with a single argument. For example, a function that takes two arguments, one from

Band one fromC, and produces outputs inD, by currying is translated into a function that takes a single argument fromCand produces as outputs functions fromBtoC.

(source: currying on wikipedia.org)

Thus, through currying, we can rewrite g as:

g: (b: B) => (c: C) => DWhat we're looking for is a lifting operation, let's call it liftA2 to distinguish it from the other functor's lift, that returns a function with the following signature:

liftA2(g): (fb: F<B>) => (fc: F<C>) => F<D>How can we obtain it? Since g is unary, we can use a functor instance and the old lift:

lift(g): (fb: F<B>) => F<(c: C) => D>But now we're stuck: functor instances provide no legal operation that allows us to unwrap (unpack) the value F<(c: C) => D> in a function (fc: F<C>) => F<D>.

Let's introduce a new abstraction called Apply that owns such an unwrapping operation (called ap):

interface Apply<F> extends Functor<F> {

readonly ap: <C, D>(

fcd: HKT<F, (c: C) => D>,

fc: HKT<F, C>

) => HKT<F, D>

}The ap is basically unpack with rearranged arguments:

unpack: <C, D>(fcd: HKT<F, (c: C) => D>) => ((fc: HKT<F, C>) => HKT<F, D>)

ap: <C, D>(fcd: HKT<F, (c: C) => D>, fc: HKT<F, C>) => HKT<F, D>thus ap can be derived from unpack (and vice versa).

It would be handy if there was another operation able to to life a value of type A in a value of type F<A>.

We introduce the Applicative abstraction that enriches Apply and contains such an operation (called of):

interface Applicative<F> extends Apply<F> {

readonly of: <A>(a: A) => HKT<F, A>

}Let's see some Applicative instance for some common data types:

Example (F = Array)

import { flatten } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

export const applicativeArray = {

map: <A, B>(fa: Array<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Array<B> =>

fa.map(f),

of: <A>(a: A): Array<A> => [a],

ap: <A, B>(

fab: Array<(a: A) => B>,

fa: Array<A>

): Array<B> => flatten(fab.map(f => fa.map(f)))

}Example (F = Option)

import {

fold,

isNone,

map,

none,

Option,

some

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable'

export const applicativeOption = {

map: <A, B>(fa: Option<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Option<B> =>

isNone(fa) ? none : some(f(fa.value)),

of: <A>(a: A): Option<A> => some(a),

ap: <A, B>(

fab: Option<(a: A) => B>,

fa: Option<A>

): Option<B> =>

pipe(

fab,

fold(

() => none,

f =>

pipe(

fa,

map(f)

)

)

)

}Example (F = Task)

import { Task } from 'fp-ts/lib/Task'

export const applicativeTask = {

map: <A, B>(fa: Task<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Task<B> => () =>

fa().then(f),

of: <A>(a: A): Task<A> => () => Promise.resolve(a),

ap: <A, B>(

fab: Task<(a: A) => B>,

fa: Task<A>

): Task<B> => () =>

Promise.all([fab(), fa()]).then(([f, a]) => f(a))

}Given an Apply instance for F can we define liftA2?

import { HKT } from 'fp-ts/lib/HKT'

import { Apply } from 'fp-ts/lib/Apply'

type Curried2<B, C, D> = (b: B) => (c: C) => D

function liftA2<F>(

F: Apply<F>

): <B, C, D>(

g: Curried2<B, C, D>

) => Curried2<HKT<F, B>, HKT<F, C>, HKT<F, D>> {

return g => fb => fc => F.ap(F.map(fb, g), fc)

}Great! But what happens if the functions accept three arguments? Do we need, yet another abstraction?

Good news, we don't, Apply is enough:

type Curried3<B, C, D, E> = (b: B) => (c: C) => (d: D) => E

function liftA3<F>(

F: Apply<F>

): <B, C, D, E>(

g: Curried3<B, C, D, E>

) => Curried3<HKT<F, B>, HKT<F, C>, HKT<F, D>, HKT<F, E>> {

return g => fb => fc => fd =>

F.ap(F.ap(F.map(fb, g), fc), fd)

}In reality, given an Apply instance we can write with the same pattern a function liftAn, no matter what n is!

Note. liftA1 is simply lift, Functor's fundamental operation.

We can now refresh our "composition table":

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure, n-ary |

liftAn(g) ∘ f |

where liftA1 = lift

Demo

An interesting property of applicative functors is that they compose: for every two functors F and G, their composition F<G<A>> is still an applicative functor.

Example

import { array } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import { Option, option } from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

export const applicativeArrayOption = {

map: <A, B>(

fa: Array<Option<A>>,

f: (a: A) => B

): Array<Option<B>> =>

array.map(fa, oa => option.map(oa, f)),

of: <A>(a: A): Array<Option<A>> => array.of(option.of(a)),

ap: <A, B>(

fab: Array<Option<(a: A) => B>>,

fa: Array<Option<A>>

): Array<Option<B>> =>

array.ap(

array.map(fab, gab => (ga: Option<A>) =>

option.ap(gab, ga)

),

fa

)

}To avoid all of this boilerplate fp-ts exports a useful helper:

import { getApplicativeComposition } from 'fp-ts/lib/Applicative'

import { array } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import { option } from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

export const applicativeArrayOption = getApplicativeComposition(

array,

option

)Not yet. There is still one last important case we have to consider: when both the programs are effectful.

Yet again we need something more, in the following chapter we'll talk about one of the most important abstractions in functional programming: monads.

Eugenio Moggi is a professor of computer science at the University of Genoa, Italy. He first described the general use of monads to structure programs.

Philip Lee Wadler is an American computer scientist known for his contributions to programming language design and type theory.

In the previous chapter we've seen that we can compose an effectful program f: (a: A) => M<B> with a pure n-ary one g, if and only if M admits an instance of an applicative functor:

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure, n-ary |

liftAn(g) ∘ f |

ove liftA1 = lift

But we have yet to solve one last, and common, case: when both programs are effectful.

Given these two effectful functions:

f: (a: A) => M<B>

g: (b: B) => M<C>what is their composition?

To handle this last case we need something more "powerful" than Functor given that it is quite common to find ourselves with multiple nested contexts.

To show why we need something more, let's see a practical example.

Example (M = Array)

Suppose we need to find the followers of the followers of a Twitter user.

interface User {

followers: Array<User>

}

const getFollowers = (user: User): Array<User> =>

user.followers

declare const user: User

const followersOfFollowers: Array<

Array<User>

> = getFollowers(user).map(getFollowers)Something's odd here: followersOfFollowers has typo Array<Array<User>> but we actually want Array<User>.

We need to un-nest (flatten) the nested arrays.

The flatten: <A>(mma: Array<Array<A>>) => Array<A> function exported from fp-ts can help us here:

import { flatten } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

const followersOfFollowers: Array<User> = flatten(

getFollowers(user).map(getFollowers)

)Good! Let's see another type:

Example (M = Option)

Suppose we want to calculate the multiplicative inverse (reciprocal) of the first element of an array of numbers:

import { head } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import {

none,

Option,

option,

some

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const inverse = (n: number): Option<number> =>

n === 0 ? none : some(1 / n)

const inverseHead: Option<Option<number>> = option.map(

head([1, 2, 3]),

inverse

)Oops, we did it again, inverseHead has typo Option<Option<number>> but we need an Option<number>.

We need to un-nest again the nested Options.

import { head } from 'fp-ts/lib/Array'

import {

isNone,

none,

Option,

option

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Option'

const flatten = <A>(mma: Option<Option<A>>): Option<A> =>

isNone(mma) ? none : mma.value

const inverseHead: Option<number> = flatten(

option.map(head([1, 2, 3]), inverse)

)All of these flatten functions...are not a coincidence. There is a functional pattern behind the scenes: all of those type constructors (and many others) admitca monad instance and

flattenis the most peculiar operation of monads

So, what is a monad?

This is how monads are presented very often...

A monad is defined by three laws:

(1) a type constructor M admitting a functor instance

(2) a function of with the following signature:

of: <A>(a: A) => HKT<M, A>(3) a flatMap function with the following signature:

flatMap: <A, B>(f: (a: A) => HKT<M, B>) => ((ma: HKT<M, A>) => HKT<M, B>)Note: remember that the HKT type is how fp-ts represents a generic type constructor, thus when we see HKT<M, X> we can think about the type constructor M applied on the type X (ovvero M<X>).

The functions of and flatMap have to obey these three laws:

flatMap(of) ∘ f = f(Left identity)flatMap(f) ∘ of = f(Right identity)flatMap(h) ∘ (flatMap(g) ∘ f) = flatMap((flatMap(h) ∘ g)) ∘ f(Associativity)

where f, g, h are all effectful functions and ∘ is the usual function composition.

When I (Giulio, ndr) saw this definition for the first time my first reaction was disconcert.

I had many questions:

- why these two operations and why do they have these signatures?

- why does the "flatMap" name?

- why do these laws have to hold true? What do they mean?

- but most importantly, where's my

flatten?

This chapter will try to answer all of these questions.

Let's get back to our problem: what is the composition of two effectful functions (also called Kleisli arrows)?

For now, I don't even know the type of such a composition.

Wait a moment... we already met an abstraction that deals specifically with composition. Do you remember what did we say about categories?

Categories capture the essence of composition

We can thus turn our composition problem in a category problem: can we find a category that models the composition of Kleisli arrows?

Heinrich Kleisli (Swiss mathematician)

Let's try building a category K (called Kleisli's category) that contains only effectful functions:

- objects which are the same of the TS category, thus all the TypeScript's types.

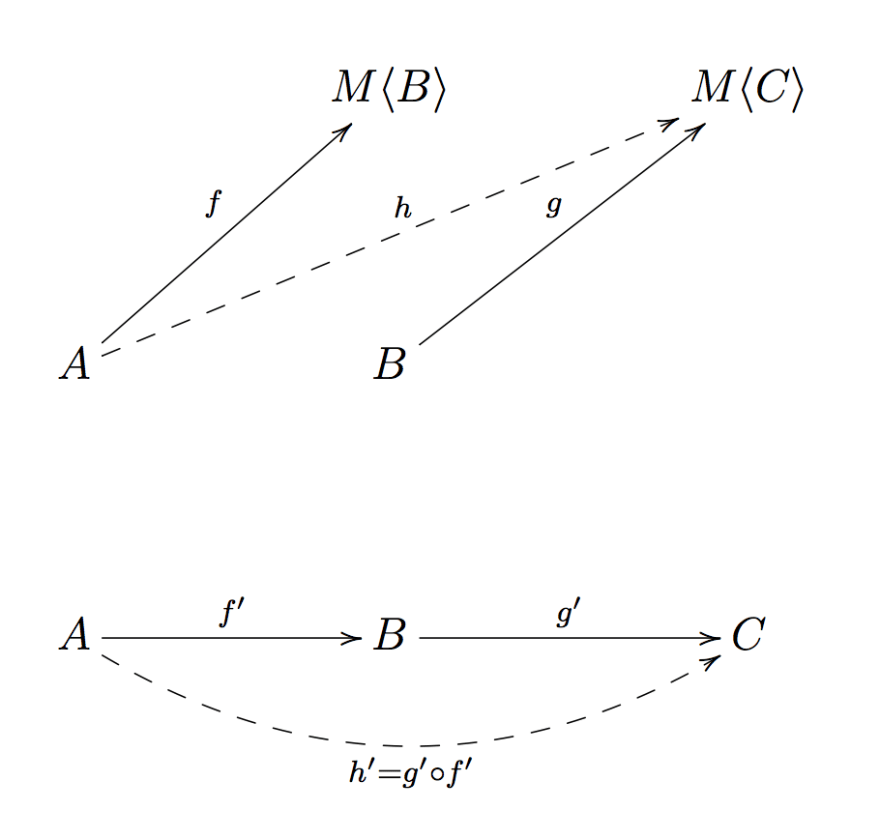

- morphism are constructed this way: every time there is a Kleisli arrow

f: A ⟼ M<B>in TS we draw an arrowf': A ⟼ Bin K.

(above the TS category, underneath the construction of K)

Thus, what is the composition of f and g in K? It is the dotted arrow called h' in the following image:

(above the TS category, underneath the construction of K)

Since h' is an arrow that goes from a A to C, there has to be a corresponding function h that goes from A to M<C> in TS.

Thus a good composition for composing f and g in TS is still an effectful function with the following signature: (a: A) => M<C>.

How can we construct such a function? Well, let's try!

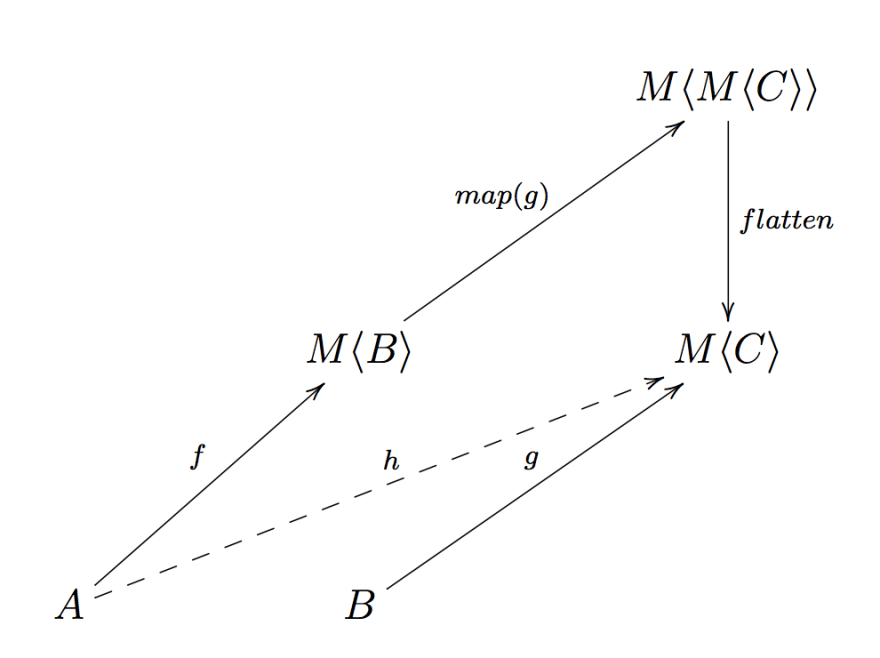

The first (1) point of the monad definition tells us that M admits a functor instance, thus we can use lift to transform the function g: (b: B) => M<C> in a function lift(g): (mb: M<B>) => M<M<C>> (I'll use the name map instead of lift, but we know they are equivalent).

(where flatMap is born)

But know we're stuck: we have no legal operation for the functor instance allowing us to de-nest a value of type M<M<C>> in a value of type M<C>, we need an additional operation called flatten.

If we can define such an operation then we can find the composition we are looking for:

h = flatten ∘ map(g) ∘ f

But wait... flatten ∘ map(g) is flatMap, that's where the name comes from!

h = flatMap(g) ∘ f

We can now update our "composition table"

| Program f | Program g | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| pure | pure | g ∘ f |

| effectful | pure, n-ary |

liftAn(g) ∘ f |