Pushup is an experiment. In terms of the development life cycle, it should be considered preview pre-release software: it is largely functional, likely has significant bugs (including potential for data loss) and/or subpar performance, but is suitable for demos and testing. It has a decent unit test suite, including fuzzing test cases for the parser. Don't count on it for anything serious yet, and expect significant breaking changes.

- Pushup - a page-oriented web framework for Go

Pushup is an experimental new project that is exploring the viability of a new approach to web frameworks in Go.

Pushup seeks to make building page-oriented, server-side web apps using Go easy. It embraces the server, while acknowledging the reality of modern web apps and their improvements to UI interactivity over previous generations.

Pushup is a program that compiles projects developed with the Pushup markup language into standalone web app servers.

There are three main aspects to Pushup:

- An opinionated project/app directory structure that enables file-based routing,

- A lightweight markup alternative to traditional web framework templates that combines Go code for control flow and imperative, view-controller-like code with HTML markup, and

- A compiler that parses that markup and generates pure Go code,

building standalone web apps on top of the Go stdlib

net/httppackage.

The core object in Pushup is the "page": a file with the .up extension that

is a mix of HTML, Go code, and a lightweight markup language that glues them

together. Pushup pages participate in URL routing by virtue of their path in

the filesystem. Pushup pages are compiled into pure Go which is then built

along with a thin runtime into a standalone web app server (which is all

net/http under the hood).

The main proposition motivating Pushup is that the page is the right level of abstraction for most kinds of server-side web apps.

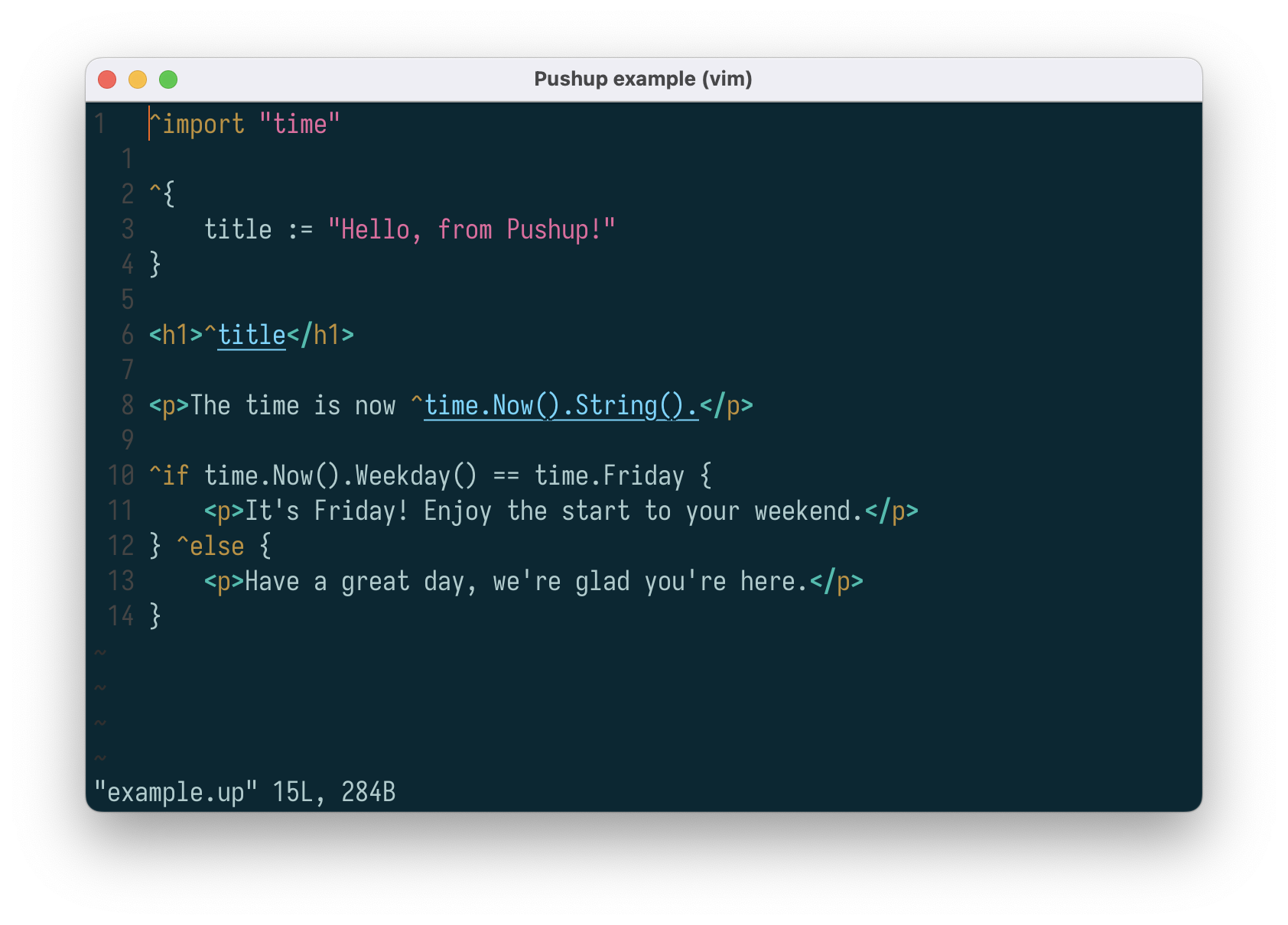

The syntax of the Pushup markup language looks like this:

^import "time"

^{

title := "Hello, from Pushup!"

}

<h1>^title</h1>

<p>The time is now ^time.Now().String().</p>

^if time.Now().Weekday() == time.Friday {

<p>It's Friday! Enjoy the start to your weekend.</p>

} ^else {

<p>Have a great day, we're glad you're here.</p>

}

You would then place this code in a file somewhere in your app/pages

directory, like hello.up. The .up extension is important and tells

the compiler that it is a Pushup page. Once you build and run your Pushup app,

that page is automatically mapped to the URL path /hello.

To make a new Pushup app, first install the main Pushup executable.

- go 1.18 or later

Make sure the directory where the go tool installs executables is in your

$PATH. It is $(go env GOPATH)/bin. You can check if this is the case with:

echo $PATH | grep $(go env GOPATH)/bin > /dev/null && echo yes || echo noDownload Pushup for your platform from the releases page.

git clone git@github.com:AdHocRandD/pushup.git

cd pushup

makeMake sure you have Go installed (at least version 1.18), and type:

go install github.com/adhocteam/pushup@latestTo create a new Pushup project, use the pushup new command.

pushup newWithout any additional arguments, it will attempt to create a scaffolded new project in the current directory. However, the directory must be completely empty, or the command will abort. To simulataneously make a new directory and generate a scaffolded project, pass a relative path as argument:

pushup new myprojectThe scaffolded new project directory consists of a directory structure for .up files and auxiliary project Go code, and a go.mod file.

Change to the new project directory if necessary, then do a pushup run,

which compiles the Pushup project to Go code, builds the app, and starts up

the server.

pushup runIf all goes well, you should see a message on the terminal that the Pushup app is running and listening on a port:

↑↑ Pushup ready and listening on 0.0.0.0:8080 ↑↑

By default it listens on port 8080, but with the -port or -unix-socket

flags you can pick your own listener.

Open http://localhost:8080/ in your browser to see the default layout and a welcome index page.

See the example directory for a demo Pushup app that demonstrates many of the concepts in Pushup and implements a few small common patterns like some HTMX examples and a simple CRUD app.

Click on "view source" at the bottom of any page in the example app to see the source of the .up page for that route, including the source of the "view source" .up page itself. This is a good way to see how to write Pushup syntax.

Pushup treats projects as their own self-contained Go module. The build

process assumes this is the case by default. But it is possible to include a

Pushup project as part of a parent Go module. See the the -module option to

pushup new.

Pushup projects have a particular directory structure that the compiler expects before building. The most minimal Pushup project would look like:

app

├── layouts

├── pages

│ └── index.up

├── pkg

└── static

go.mod

Pushup pages are the main units in Pushup. They are a combination of logic and content. It may be helpful to think of them as both the controller and the view in a MVC-like system, but colocated together in the same file.

They are also the basis of file-based routing: the name of the Pushup file, minus the .up extension, is mapped to the portion of the URL path for routing.

Layouts are HTML templates that used in common across multiple pages. They are

just HTML, with Pushup syntax as necessary. Each page renders its contents, and

then the layout inserts the page contents into the template with the

^outputSection("contents") Pushup expression.

Static media files like CSS, JS, and images, can be added to the app/static

project directory. These will be embedded directly in the project executable

when it is built, and are accessed via a straightforward mapping under the

"/static/" URL path.

Pushup maps file locations to URL route paths. So about.up becomes

/about, and foo/bar/baz.up becomes /foo/bar/baz. More TK ...

You can print a list of the app's routes with the command:

pushup routesIf the filename of a Pushup page starts with a $ dollar sign, the portion

of the URL path that matches will be available to the page via the getParam()

Pushup API method.

For example, let's say there is a Pushup page at app/pages/people/$id.up.

If a browser visits the URL /people/1234, the page can access it like a named

parameter with the API method getParam(), for example:

<p>ID: ^getParam(req, "id")</p>

would output:

<p>ID: 1234</p>The name of the parameter is the word following the $ dollar sign, up to a dot

or a slash. Conceptually, the URL route is /people/:id, where :id is the

named parameter that is substituted for the actual value in the request URL.

Directories can be dynamic, too. app/pages/products/$pid/details.up maps

to /products/:pid/details.

Multiple named parameters are allowed, for example, app/pages/users/$uid/projects/$pid.up

maps to /users/:uid/projects/:pid.

Inline partials allow pages to denote subsections of themselves, and allow for these subsections (the inline partials) to be rendered and returned to the client independently, without having to render the entire enclosing page.

Typically, partials in templating languages are stored in their own files, which are then transcluded into other templates. Inline partials, however, are partials declared and defined in-line a parent or including template.

Inline partials are useful when combined with enhanced hypertext solutions (eg., htmx). The reason is that these sites make AJAX requests for partial HTML responses to update portions of an already-loaded document. Partial responses should not have enclosing markup such as base templates applied by the templating engine, since that would break the of the document they are being inserted into. Inline partials in Pushup automatically disable layouts so that partial responses have just the content they define.

The ability to quickly define partials, and not have to deal with complexities like toggling off layouts, makes it easier to build enhanced hypertext sites.

All modern web frameworks should implement a standard set of functionality, spanning from safety to convenience. As of this writing, Pushup does not yet implement them all, but aspires to prior to any public release.

By default, all content is HTML-escaped, so in general it is safe to directly place user-supplied data into Pushup pages. (Note that the framework does not (yet) do this in your Go code, data from form submissions and URL queries should be validated and treated as unsafe.)

For example, if you wanted to display on the page the query a user searched for, this is safe:

^{ query := req.FormValue("query") }

<p>You search for: <b>^query</b></p>

Pushup is a mix of a new syntax consisting of Pushup directives and keywords, Go code, and HTML markup.

Parsing a .up file always starts out in HTML mode, so you can just put plain HTML in a file and that's a valid Pushup page.

When the parser encounters a '^' character (caret, ASCII 0x5e) while in HTML mode, it switches to parsing Pushup syntax, which consists of simple directives, control flow statements, block delimiters, and Go expressions. It then switches to the Go code parser. Once it detects the end of the directive, statement, or expression, it switches back to HTML mode, and parsing continues in a similar fashion.

Pushup uses the tokenizers from the go/scanner and golang.org/x/net/html packages, so it should be able to handle any valid syntax from either language.

Use ^import to import a Go package into the current Pushup page. The syntax

for ^import is the same as a regular Go import declaration

Example:

^import "strings"

^import "strconv"

^import . "strings"

Layouts are HTML templates that enclose the contents of a Pushup page.

The ^layout directive instructs Pushup what layout to apply the contents of

the current page.

The name of the layout following the directive is the filename in the

layouts directory minus the .up extension. For example, ^layout main

would try to apply the layout located at app/layouts/main.up.

^layout is optional - if it is not specified, pages automatically get the

"default" layout (app/layouts/default.up).

Example:

^layout homepage

A page may choose to have no layout applied - that is, the contents of the page

itself are sent directly to the client with no enclosing template. In this case,

use the ! name:

^layout !

To include statements of Go in a Pushup page, type ^{ followed by your

Go code, terminating with a closing }.

The scope of a ^{ ... } in the compiled Go code is equal to its surrounding

markup, so you can define a variable and immediately use it:

^{

name := "world"

}

<h1>Hello, ^name!</h1>

Because the Pushup parser is only looking for a balanced closing }, blocks

can be one-liners:

^{ name := "world"; greeting := "Hello" }

<h1>^greeting, ^name!</h1>

A Pushup page can have zero or many ^{ ... } blocks.

A handler is similar to ^{ ... }. The difference is that there may be at most

one handler per page, and it is run prior to any other code or markup on the

page.

A handler is the appropriate place to do "controller"-like (in the MVC sense) actions, such as HTTP redirects and errors. In other words, any control flow based on the nature of the request, for example, redirecting after a successful POST to create a new object in a CRUD operation.

Example:

^handler {

if req.Method == "POST" && formValid(req) {

if err := createObjectFromForm(req.Form); err == nil {

return http.Redirect(w, req, "/success/", http.StatusSeeOther)

return nil

} else {

// error handling

...

}

...

}

...

Note that handlers (and all Pushup code) run in a method on a receiver that

implements Pushup's Responder interface, which is

interface Responder {

Respond(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request) error

}To exit from a page early in a handler (i.e., prior to any normal content being rendered), return from the method with a nil (for success) or an error (which will in general respond with HTTP 500 to the client).

^if takes a boolean Go expression and a block to conditionally render.

Example:

^if query := req.FormValue("query"); query != "" {

<p>Query: ^query</p>

}

^for takes a Go "for" statement condition, clause, or range, and a block,

and repeatedly executes the block.

Example:

^for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

<p>Number ^i</p>

}

Simple Go expressions can be written with just ^ followed by the expression.

"Simple" means:

- variable names (eg.,

^x) - dotted field name access of structs (eg.,

^account.name) - function and method calls (eg.,

^strings.Repeat("x", 3)) - index expressions (eg.,

a[x])

Example:

^{ name := "Paul" }

<p>Hello, ^name!</p>

Outputs:

<p>Hello, Paul!</p>Notice that the parser stops on the "!" because it knows it is not part of a Go variable name.

Example:

<p>The URL path: ^req.URL.Path</p>

Outputs:

<p>The URL path: /foo/bar</p>Example:

^import "strings"

<p>^strings.Repeat("Hello", 3)</p>

Outputs:

<p>HelloHelloHello</p>Explicit expressions are written with ^ and followed by any valid Go

expression grouped by parentheses.

Example:

^{ numPeople := 4 }

<p>With ^numPeople people there are ^(numPeople * 2) hands</p>

Outputs:

<p>With 4 people there are 8 hands</p>Pushup layouts can have sections within the HTML document that Pushup pages can define with their own content to be rendered into those locations.

For example, a layout could have a sidebar section, and each page can set its own sidebar content.

In a Pushup page, sections are defined with the keyword like so:

^section sidebar {

<article>

<h1>This is my sidebar content</h1>

<p>More to come</p>

</article>

}

Layouts can output sections with the outputSection function.

<aside>

^outputSection("sidebar")

</aside>

Layouts can also make sections optional, by first checking if a page has set a

section with sectionDefined(), which returns a boolean.

^if sectionDefined("sidebar") {

<aside>

^outputSection("sidebar")

</aside>

}

Checking for if a section was set by a page lets a layout designer provide default markup that can be overridden by a page.

^if sectionDefined("title") {

<title>

^outputSection("title")

</title>

} ^else {

<title>Welcome to our site</title>

}

Pushup pages can declare and define inline partials with the ^partial

keyword.

...

<section>

<p>Elements</p>

^partial list {

<ul>

<li>Ag</li>

<li>Na</li>

<li>C</li>

</ul>

}

</section>

...

A request to the page containing the initial partial will render normally,

as if the block where not wrapped in ^partial list { ... }.

A request to the page with the name of the partial appended to the URL path will respond with just the content scoped by the partial block.

For example, if the page above had the route /elements/, then a request to

/elements/list would output:

<ul>

<li>Ag</li>

<li>Na</li>

<li>C</li>

</ul>Inline partials can nest arbitrarily deep.

...

^partial leagues {

<p>Leagues</p>

^partial teams {

<p>Teams</p>

^partial players {

<p>Players</p>

}

}

}

...

To request a nested partial, make sure the URL path is preceded by

each containing partial's name and a forward slash, for example,

/sports/leagues/teams/players.

There is a vim plugin in the vim-pushup directory. You should be able to symlink it into your plugin manager's path. Alternatively, to install it manually:

- Locate or create a

syntaxdirectory in your vim config directory (Usually~/.vim/syntaxfor vim or~/.config/nvim/syntaxfor neovim) - Copy

syntax/pushup.viminto that directory - Locate or create a

ftdetectdirectory in your vim config directory (Usually~/.vim/syntaxfor vim or~/.config/nvim/syntaxfor neovim) - Copy

ftdetect/pushup.viminto that directory