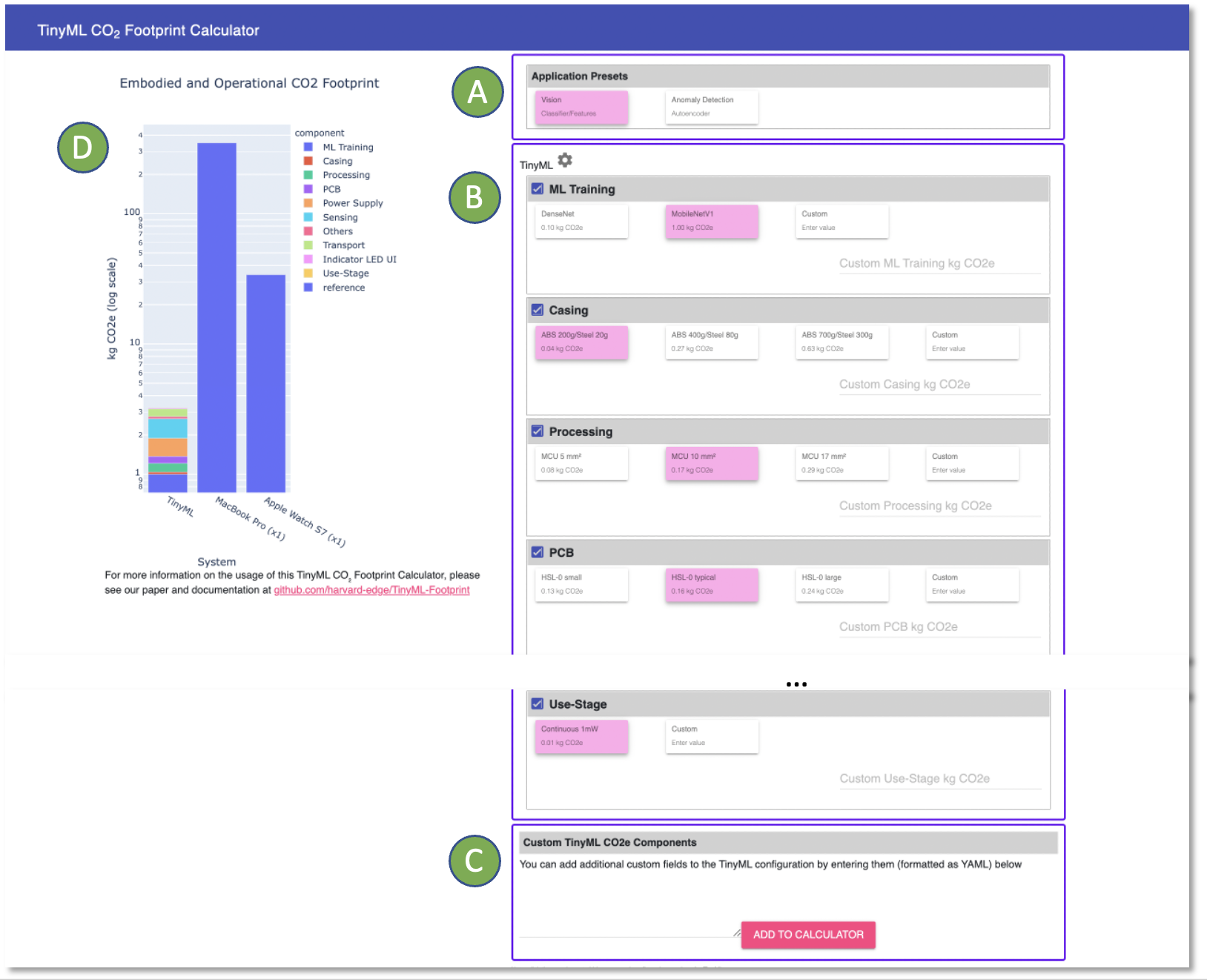

Plug in play calculator for measuring footprint of complete TinyML system available here!

Below is a walkthrough of how to use it:

(A) Select a TinyML application as your baseline starting point, which sets your system to preset defaults.

(B) Customize components based on your specific application needs and requirements. You can select one of the hardware specification levels we provide from Pirson & Bol [1] or provide a custom value if you know the component's footprint for your own system.

(C) Add additional components to include in your system and their associated footprints if you have more components the ones we provide.

(D) Visualize the results in the plot and measure your TinyML system's footprint! You can compare with an Apple Watch S7 and Macbook Pro for reference.

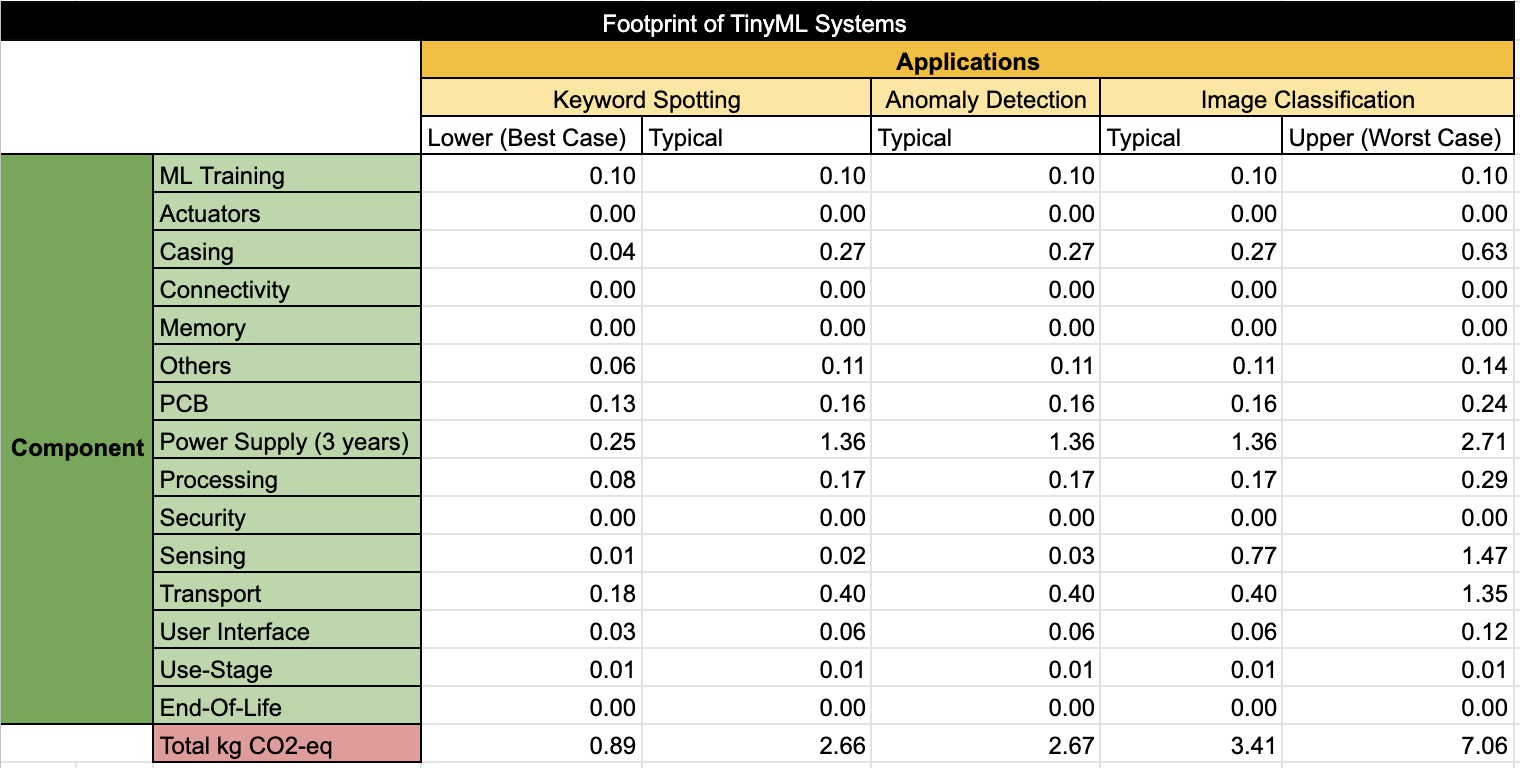

Below is the embodied & operational fooprint in kg CO2-eq for each component of a TinyML System for 3 different applications using Pirson & Bol [1].

- Model Training numbers are taken from Dodge et al. [2] using DenseNet models, which serve as an upper bound as these models are much larger, and require more energy to train, than typical TinyML models.

- Use-Stage of the hardware life cycle (i.e. operational footprint) is calculated as the kg CO2-eq of recharging the power supply using emission factor for electricity consumed from EPA [3], accounting for three years (to be consistent with Apple’s analysis [4]) of continuous use at 1 mW, an average estimate of the power used by current TinyML systems in the MLPerf Tiny Benchmark [5], [6].

- End-of-life stage taken to be negliblige contribution (i.e. <1%) to system footprint as shown in multiple similar cases such as Apple Watch [4] and STMicroelectronics Microcontroller [7].

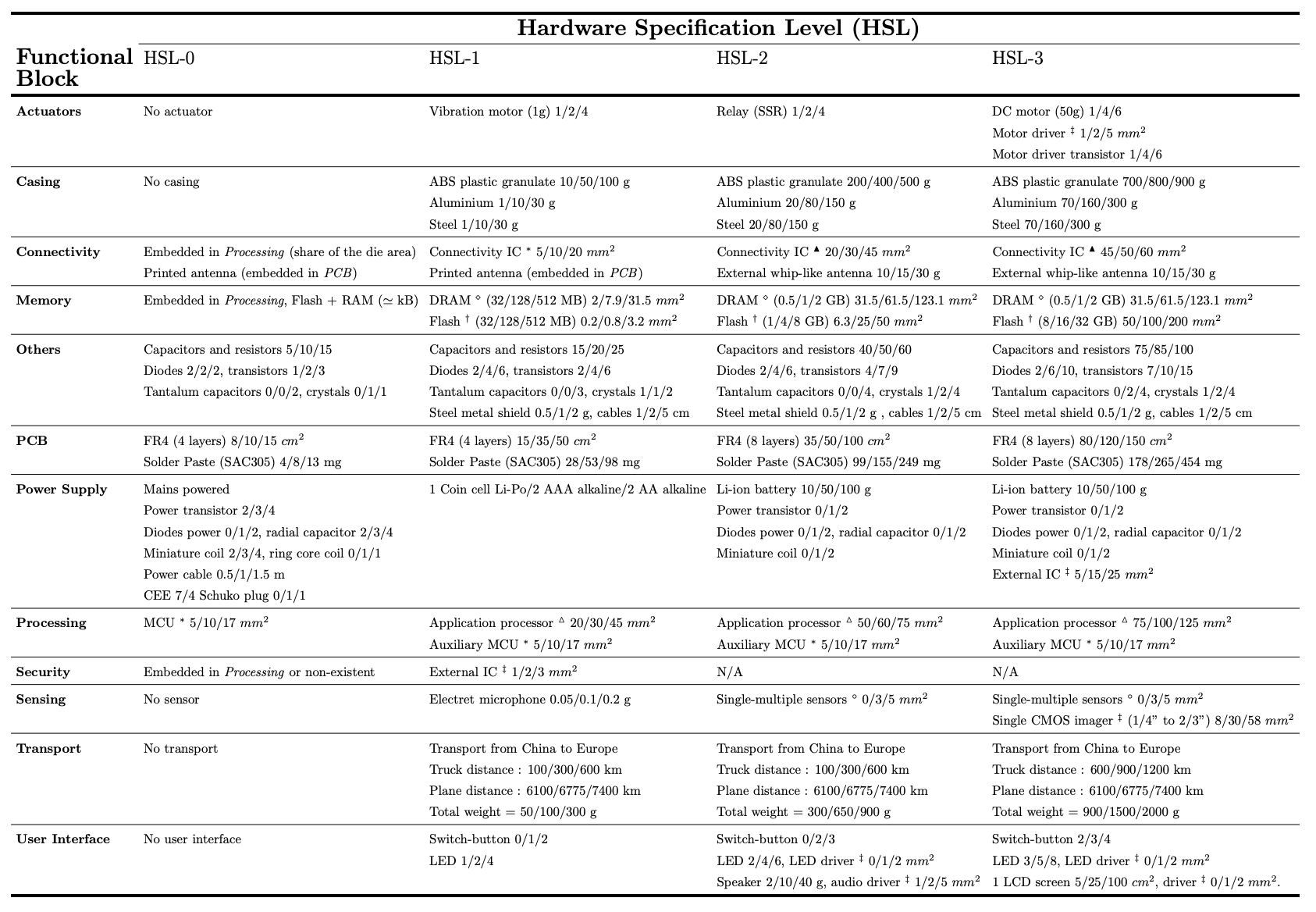

Pirson & Bol [1] breakdown any IoT device into generic functional blocks: processing, memory, actuators, casing, connectiv- ity, PCB, power supply, security, sensing, transport, user interface, and others circuit components (e.g. resistors, capacitors, diodes, etc.). Within these blocks, there are different specifications that need to be met depending on the application and its requirements, which we use.

To show our TinyML System footprints are reasonable, here we explain our selections for each TinyML System component from the specification levels provided in the image below from Pirson & Bol [1]. All three TinyML application footprints shown above (i.e. Keyword Spotting, Anomaly Detection, and Image Classification) contain the same system components except for the sensing modules as sensing requirement is different for each application. Note that in our paper we have only included Keyword Spotting (best case) and Image Classification (typical case & worst case) to capture the range of TinyML System footprints while limiting text appropriately.

No actuators are typically needed in the context of TinyML systems, especially not in the applications outlined earlier. Typically TinyML is used to perform on-device sensor analytics that can then relay some information to another system to take appropariate action.

Ideally TinyML should be able to be deployed in a "stick-and-peel" fashion, making the form factor and casing required very small. However, a 50-100g platic encasing as specified in HSL-1 is more than enough, and even in 10g in most cases ideally. For reference here is what 100g ABS plastic case look like as outlined in HSL-1 upper bound for this component.

One of the main premises of TinyML is running the ML on device, rather than being reliant on the cloud. That being said some minimal communication will always be needed. However, typically we do not see an external IC for communication on TinyML systems and the communication embedded in the processor as mentioned in HSL-0 is what is used and is sufficient.

TinyML is performed on MCUs with only KBs of memory. This fits HSL-0 for this category; a separate, external chip for memory is not typical in TinyML. See Zhang et al. [8] for examples of MCUs with only KBs of memory running TinyML. HSL-0 should suffice for most TinyML applications.

Other circuit components (e.g. resistors, capacitors, diodes, etc.) are not needed for running TinyML and HSL-0 is sufficient for this category.

The Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense is built specifically with the intent of running TinyML [9][10]. The printed circuit board (PCB) can be found to be 8.1 square centimeters, showing HSL-0 for this component is sufficient.

A typical lithium ion battery for the power assumed to run TinyML (i.e. 1mW) on device will allow the systems to run for years with recharge required at a practical interval, compared to say a coin cell battery. The calculations performed to conclude this assumed a battery with 3.6V nominal voltage running at 2000 milliamp hours which we found to be reasonable and typical for a lithium-ion battery.

HSL-0 includes a standalone MCU. All other HSLs include an application processor which is not necessary and needed for running TinyML.

Separate ICs for security (i.e. HSL-1) are not typically found in TinyML devices. We find any security embedded in the processing (i.e. HSL-0) is sufficient at the moment and more common.

The sensing hardware specification level differed depending on application. For keyword spotting a microphone (i.e. HSL-1) is sufficient. Typically anomaly detection involves some sort of fusion of sensors (i.e. HSL-2). Finally, image classification requires a camera (i.e. HSL-3).

The total weight of the TinyML system, even assuming 100g for casing in the worst case, should fall between the range provided per TinyML device in HSL-1 for transporting

An UI is not typically needed for TinyML systems since humans are not typically interacting much with these systems once deployed in the wild but some LEDs or switch buttons should be sufficient to interact or signal anything to the user. For this reason, we selected HSL-1 for this component.

[1] Pirson, T., & Bol, D. (2021). Assessing the embodied carbon footprint of IoT edge devices with a bottom-up life-cycle approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 322, 128966.

[2] Dodge, J., Prewitt, T., Tachet des Combes, R., Odmark, E., Schwartz, R., Strubell, E., ... & Buchanan, W. (2022, June). Measuring the Carbon Intensity of AI in Cloud Instances. In 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 1877-1894).

[3] https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gases-equivalencies-calculator-calculations-and-references

[4] https://www.apple.com/in/environment/pdf/products/watch/Apple_Watch_Series7_PER_Sept2021.pdf

[5] Banbury, C., Reddi, V. J., Torelli, P., Holleman, J., Jeffries, N., Kiraly, C., ... & Xuesong, X. (2021). Mlperf tiny benchmark. In 2021 Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) Datasets and Benchmarks.

[6] https://mlcommons.org/en/inference-tiny-07/

[7] https://www.st.com/content/st_com/en/about/st_approach_to_sustainability/sustainability-priorities/sustainable-technology/eco-design/footprint-of-a-microcontroller.html

[8] Zhang, Y., Suda, N., Lai, L., & Chandra, V. (2017). Hello edge: Keyword spotting on microcontrollers. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.07128.

[9] https://store-usa.arduino.cc/products/arduino-nano-33-ble-sense

[10] https://store-usa.arduino.cc/products/arduino-tiny-machine-learning-kit