Input matcher is a mechanism for evaluating the similarity between user inputs like mouse clicks, key presses, dragging. It first captures the input, then performs matching. The output - a coefficient of how similar are the inputs.

# Install npm dependencies

npm install

# Run the React app

npm start

# Run the tests

npm test

# Generate a documentation (in docs/) with typedoc

npm run docsWe will look into src folder:

- ui/ - is a small React app tasked to show the capabilities of the input matcher

- core/ - represents the capturing/matching logic

- matcher/ - contains matcher logic

- AbstractInputMatcher.ts - contains

AbstractInputMatcherwhich describes matcher's properties and behavior - Algorithms.ts - contains a set of functions which implement the needed algorithms for matching

- Config.ts - configuration file

- InputMatcher.ts - contains

InputMatcher; it's a concrete implementation of the above - Matcher.ts - sort of a factory (

getMatcher) that provides an instance ofAbstractInputMatcheraccross the app

- AbstractInputMatcher.ts - contains

- tests/ - no need of explanation

- utils/

- Parser.ts - has the logic of the parser and stringifier of input (

parseSetandstringifySet); the string format is suitable for transportation FE-BE

- Parser.ts - has the logic of the parser and stringifier of input (

- index.ts - simple facade (a.k.a. barrel) of the core

- InputCatcher.ts - contains

InputCatcher; the logic behind capturing of the input from the DOM - InputTypes.ts - contains all standardized types for clicks, movements, the set, etc.

- matcher/ - contains matcher logic

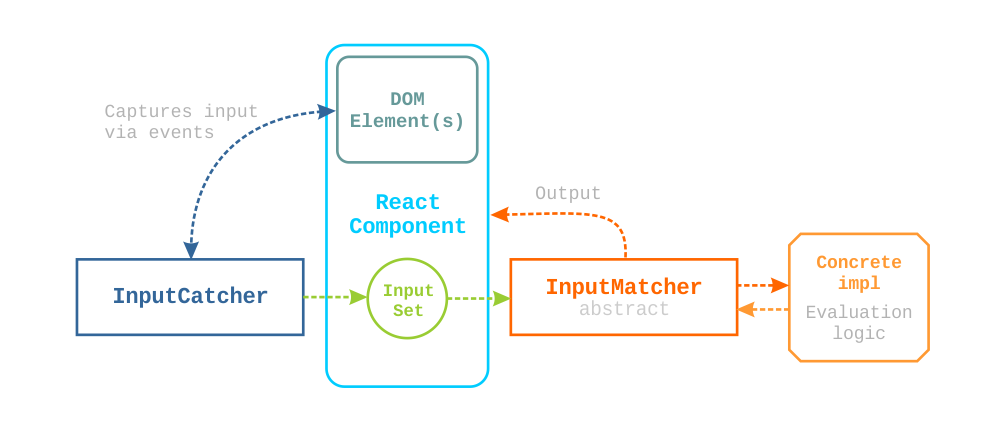

The scheme describes the idea behind the input matcher. Note that the React app is there just for the demo. The core is framework-agnostic.

The InputMatcher and InputCatcher don't know about the existance of each other. They are completely decoupled. The InputCatcher provides DOM events to the UI with which it can listen for the input. The generated InputSet is then passed to the InputMatcher which performs the comparison. In the scheme, we assume that the InputMatcher has already accepted a training set(s).

The idea is to:

- Use pattern recognition or algorithm for finding the similarities between two curves/set of points for each

MouseMove(Possible candidates are Dynamic Time Wrapping and Frechet Distance) - Determine if the clicks are within a specific radius for each

MouseClick(Distance to a point within specified radius) - Perform approximate string matching for each

KeySequence(Damerau–Levenshtein distance; Improvement of Levenshtein that'll work for us)

So far, these are some common techniques. Here arises:

Problem 1. "How are we going to make all of these work together?". The possible solution:

Each algorithm will return a rate between 0 and 1 separately. Let's say we have:

Training set:

[ Click A, Move B, Click C, PressSeq D ]

Input set:

[ Click A1, Move B1, Click C1, PressSeq D1 ]

and A != A1, B ~ B1, C = C1, D ~ D1, then after comparison, we can end up with:

[ 0.1, 0.88, 1, 0.74 ] // Random numbers for the demoIn the end we can simply take the average of the array above and conclude that we have 68% similarity. Unfortunately, this looks promising only for the best-case scenario. Then we encounter:

Problem 2. "Sequentiality - how we can tackle it?"

What if the input set is like this:

[ Move B1, Click A1, Click C1, PressSeq D1 ]

We can't compare A and B1 because they are different types. Even if they were the same type, we can't be sure if the A is intended to represent/replicate the B1. That's why we should check the nearby actions as well. Targetting the neighbors hence n - 1, n and n + 1, appears to be reasonable. Anything farther from this can be considered as a deviation from the original input, so for example, it won't matter if n resembles n + 3 or not. Of course, only one of the evaluated actions will receive a coefficient - the one with the highest one because the resemblence is the greatest.

Since we have to take in count the positions of the actions now, the scalar output array with coefficients won't help us. We will introduce a new object, the OutputSet which will keep the position offset and the coefficient:

Training set:

[ ..., Move A, Move B, ... ]

Input set:

[ ..., Move A1, Click A2, Move AB, Move B1, PressSeq B2, ... ]

The algorithm will:

-

Move A will check n - 1, n and n + 1

- n - 1 = Move A1: Coefficient is 0.75, so the object will be:

{ pos: -1, coef: 0.75 } - n = Click A2: Different types, so:

{ pos: 0, coef: 0 } - n + 1 = Move AB: Coefficient is 0.28, but 0.75 > 0.28, so:

{ pos: 1, coef: 0 }

- n - 1 = Move A1: Coefficient is 0.75, so the object will be:

-

Move B will check n - 1, n and n + 1

- n - 1 = Move AB: Coefficient is 0.88, and since we already have result for Move AB although 0, we will take the greater coefficient, so 0.88 > 0 which will result in:

{ pos: -1, coef: 0.88 }. If Move A1 coefficient was less than 0.28 and respectively Move AB = 0.28, we would still pick 0.88 in that case because 0.88 > 0.28. - n = Move B1: Coefficient is 0.80, but since we have greater coefficient that is associated with Move B (0.88), we will:

{ pos: 0, coef: 0 } - n + 1 = PressSeq B2: Different types, so:

{ pos: 1, coef: 0 }

- n - 1 = Move AB: Coefficient is 0.88, and since we already have result for Move AB although 0, we will take the greater coefficient, so 0.88 > 0 which will result in:

* Values are randomly selected for the example.

Output set:

[

...,

{ pos: -1, coef: 0.75 }, // Move A1

{ pos: 0, coef: 0 }, // Click A2

{ pos: -1, coef: 0.88 }, // Move AB

{ pos: 0, coef: 0 }, // Move B1

{ pos: 1, coef: 0 }, // PressSeq B2

...

]Now we have to address the differences in the positions somehow. This can happen with adding rates the farther from the original action we are heading. For example:

[ ..., (n - 2) * 0.33 , (n - 1) * 0.66 , (n) * 1, (n + 1) * 0.66, (n + 2) * 0.33, ... ]

Note we are using n +/- 2 to depict the decreasing rates. The rates are randomly picked as well.

So in the previous example with the subset of actions, we will get:

[ ..., 0.66 * 0.75, 1 * 0, 0.66 * 0.88, 1 * 0, 0.66 * 0, ... ] ~ 0.22Problem 3. "Unrepresented actions."

Let's imagine we have the following evaluation:

- Move X

- n - 1 = 0.25

- n = 0.50

- n + 1 = 0.75

- Move Y

- n - 1 = 0.90

- n = 0.5

- n + 1 = 0.2

so Move X is represented by its right neighbor (n + 1), which is 0.75 and Move Y by its left one, which is 0.90. However Move X's right neighbor is the same as Move Y's left neighbor, so we should pick the higher one which results in 0.90 for the action. In the end, it turns out that Move X is left unrepresented by any other action from the input set. We could now select the second greatest coefficient hence n = 0.50 to represent it but realistically, we are always searching for the highest resemblance meaning that even if we choose the 50%, it is for sure not the action we are looking for which means that having a zero coefficient is fine.

Problem 4. "Difference in length between training and input sets."

We can't guarantee the equal length of both of the sets. That's why in the case with difference, we should use zero-coefficient elements in order to address the missing actions which in practice should affect the output. This can be realized by filling either the training or input set, depending which one is longer, until the same length is reached.

Problem 5. "Multiple training sets."

In this scenario, we are comparing the input set with each training set and then taking the average.