This is just a simple demonstration to get a basic understanding of how kubernetes works while working step by step. I learnt kubernetes like this and made this repo to solve some problems that I faced during my learning experience so that it might help other beginners. We won't be going into depth about docker 😊 but will see sufficient content to get you basic understanding to learn and work with kubernetes. ✌️ Hope you enjoy learning. If you like it please give it a 🌟.

Important :- By seeing size of readme you might have second thoughts but to be honest if you work from start you won't experience any problem and learn along the way.

- Requirements

- Docker

- Kubernetes

- What is Kubernetes

- Working with Kubernetes

- Setting up a Kubernetes cluster

- Running a local single node Kubernetes cluster with Minikube

- Checking Status of cluster

- Deploying your Node app

- Listing Pods

- Accessing your web application

- Horizontally scaling the application

- Displaying the Pod IP and Pods Node when listing Pods

- Accessing Dashboard when using Minikube

- Pods

- Examining a YAML descriptor of an existing pod

- Introducing the main parts of a POD definition

- Creating a simple YAML descriptor for a pod

- Using kubectl create to create the pod

- Retrieving a PODs logs with Kubectl logs

- Forwarding a Local Network to a port in the Pod

- Introducing labels

- Listing subsets of pods through label selectors

- Using labels and selectors to constrain pod scheduling

- Annotating pods

- Using namespace to group resources

- Stopping and removing pods

- Replication and other controllers: Deploying managed pods

- You need to have docker installed for your OS

- minikube installed for running locally

- kubectl installed.

Docker is a platform for packaging, distribution and running applications. It allows you to package your application together with its whole environment. This can be either a few libraries that the app requires or even all the files that are usually available on the filesystem of an installed operating system. Docker makes it possible to transfer this package to a central repository from which it can then be transferred to any computer running Docker and executed there

Three main concepts in Docker comprise this scenario:

- Images :— A Docker based container image is something you package your application and its environment. It contains the filesystem that will be available to the application and other metadata, such as the path to the executable that should be executed when the image is run.

- Registries :- A Docker Registry is a repository that stores your Docker images and facilitates easy sharing of those images between different people and computers. When you build your image, you can either run it on the computer you’ve built it on, or you can push (upload) the image to a registry and then pull (download) it on another computer and run it there. Certain registries are public, allowing anyone to pull images from it, while others are private, only accessible to certain people or machines.

- Containers :- A Docker-based container is a regular Linux container created from a Docker-based container image. A running container is a process running on the host running Docker, but it’s completely isolated from both the host and all other processes running on it. The process is also resource-constrained, meaning it can only access and use the number of resources (CPU, RAM, and so on) that are allocated to it.

You first need to create a container image. We will use docker for that. We are creating a simple web server to see how kubernetes works.

- create a file

app.jsand copy this code into it

const http = require('http');

const os = require('os');

console.log("Kubia server starting...");

var handler = function (request, response) {

console.log("Received request from " + request.connection.remoteAddress);

response.writeHead(200);

response.end("You've hit " + os.hostname() + "\n");

};

var www = http.createServer(handler);

www.listen(8080);Now we will create a docker file that will run on a cluster when we create a docker image.

- create a file named

Dockerfileand copy this code into it.

FROM node:8

RUN npm i

ADD app.js /app.js

ENTRYPOINT [ "node", "app.js" ]

Make sure your docker server is up and running. Now we will create a docker image in our local machine. Open your terminal in the current project's folder and run

docker build -t kubia .

You’re telling Docker to build an image called kubia based on the contents of the current directory (note the dot at the end of the build command). Docker will look for the Dockerfile in the directory and build the image based on the instructions in the file.

Now check your docker image created by running

docker images

This command lists all the images.

docker run --name kubia-container -p 8080:8080 -d kubia

This tells Docker to run a new container called kubia-container from the kubia image. The container will be detached from the console (-d flag), which means it will run in the background. Port 8080 on the local machine will be mapped to port 8080 inside the container (-p 8080:8080 option), so you can access the app through localhost.

Run in your terminal

curl localhost:8080

You’ve hit 44d76963e8e1

You can list all your running containers by this command.

docker ps

The docker ps command only shows the most basic information about the containers.

Also to get additional information about a container run this command

docker inspect kubia-container

You can see all the container by

docker ps -a

The Node.js image on which you’ve based your image contains the bash shell, so you can run the shell inside the container like this:

docker exec -it kubia-container bash

This will run bash inside the existing kubia-container container. The bash process will have the same Linux namespaces as the main container process. This allows you to explore the container from within and see how Node.js and your app see the system when running inside the container. The -it option is shorthand for two options:

- -i, which makes sure STDIN is kept open. You need this for entering commands into the shell.

- -t, which allocates a pseudo terminal (TTY).

Let’s see how to use the shell in the following listing to see the processes running in the container.

root@c61b9b509f9a:/# ps aux

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

root 1 0.4 1.3 872872 27832 ? Ssl 06:01 0:00 node app.js

root 11 0.1 0.1 20244 3016 pts/0 Ss 06:02 0:00 bash

root 16 0.0 0.0 17504 2036 pts/0 R+ 06:02 0:00 ps auxYou see only three processes. You don’t see any other processes from the host OS.

Like having an isolated process tree, each container also has an isolated filesystem. Listing the contents of the root directory inside the container will only show the files in the container and will include all the files that are in the image plus any files that are created while the container is running (log files and similar), as shown in the following listing.

root@c61b9b509f9a:/# ls

app.js bin boot dev etc home lib lib64 media mnt opt package-lock.json proc root run sbin srv sys tmp usr varIt contains the app.js file and other system directories that are part of the node:8 base image you’re using. To exit the container, you exit the shell by running the exit command and you’ll be returned to your host machine (like logging out of an ssh session, for example).

docker stop kubia-container

This will stop the main process running in the container and consequently stop the container because no other processes are running inside the container. The container itself still exists and you can see it with docker ps -a. The -a option prints out all the containers, those running and those that have been stopped. To truly remove a container, you need to remove it with the docker rm command:

docker rm kubia-container

This deletes the container. All its contents are removed and it can’t be started again.

The image you’ve built has so far only been available on your local machine. To allow you to run it on any other machine, you need to push the image to an external image registry. For the sake of simplicity, you won’t set up a private image registry and will instead push the image to Docker Hub

Before you do that, you need to re-tag your image according to Docker Hub’s rules. Docker Hub will allow you to push an image if the image’s repository name starts with your Docker Hub ID. You create your Docker Hub ID by registering at hub-docker. I’ll use my own ID (knrt10) in the following examples. Please change every occurrence with your own ID.

Once you know your ID, you’re ready to rename your image, currently tagged as kubia, to knrt10/kubia (replace knrt10 with your own Docker Hub ID):

docker tag kubia knrt10/kubia

This doesn’t rename the tag; it creates an additional tag for the same image. You can confirm this by listing the images stored on your system with the docker images command, as shown in the following listing.

docker images | head

As you can see, both kubia and knrt10/kubia point to the same image ID, so they’re in fact one single image with two tags.

Before you can push the image to Docker Hub, you need to log in under your user ID with the docker login command. Once you’re logged in, you can finally push the yourid/kubia image to Docker Hub like this:

docker push knrt10/kubia

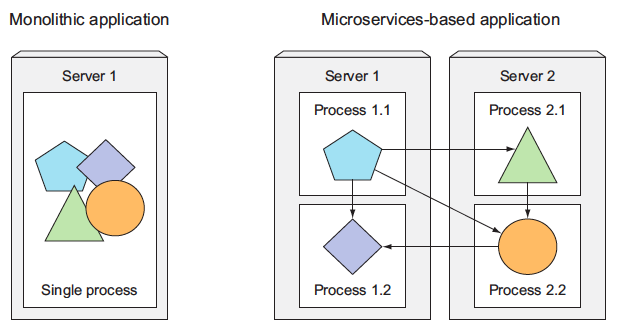

Years ago, most software applications were big monoliths, running either as a single process or as a small number of processes spread across a handful of servers. Today, these big monolithic legacy applications are slowly being broken down into smaller, independently running components called microservices. Because microservices are decoupled from each other, they can be developed, deployed, updated, and scaled individually. This enables you to change components quickly and as often as necessary to keep up with today’s rapidly changing business requirements.

But with bigger numbers of deployable components and increasingly larger datacenters, it becomes increasingly difficult to configure manage, and keep the whole system running smoothly. It’s much harder to figure out where to put each of those components to achieve high resource utilization and thereby keep the hardware costs down. Doing all this manually is hard work. We need automation, which includes automatic scheduling of those components to our servers, automatic configuration, supervision, and failure-handling. This is where Kubernetes comes in.

Kubernetes enables developers to deploy their applications themselves and as often as they want, without requiring any assistance from the operations (ops) team. But Kubernetes doesn’t benefit only developers. It also helps the ops team by automatically monitoring and rescheduling those apps in the event of a hardware failure. The focus for system administrators (sysadmins) shifts from supervising individual apps to mostly supervising and managing Kubernetes and the rest of the infrastructure, while Kubernetes itself takes care of the apps.

Each microservice runs as an independent process and communicates with other microservices through simple, well-defined interfaces (APIs). Refer to below image

Image taken from other source

Microservices communicate through synchronous protocols such as HTTP, over which they usually expose RESTful (REpresentational State Transfer) APIs, or through asynchronous protocols such as AMQP (Advanced Message Queueing Protocol). These protocols are simple, well understood by most developers, and not tied to any specific programming language. Each microservice can be written in the language that’s most appropriate for implementing that specific microservice.

Because each microservice is a standalone process with a relatively static external API, it’s possible to develop and deploy each microservice separately. A change to one of them doesn’t require changes or redeployment of any other service, provided that the API doesn’t change or changes only in a backward-compatible way.

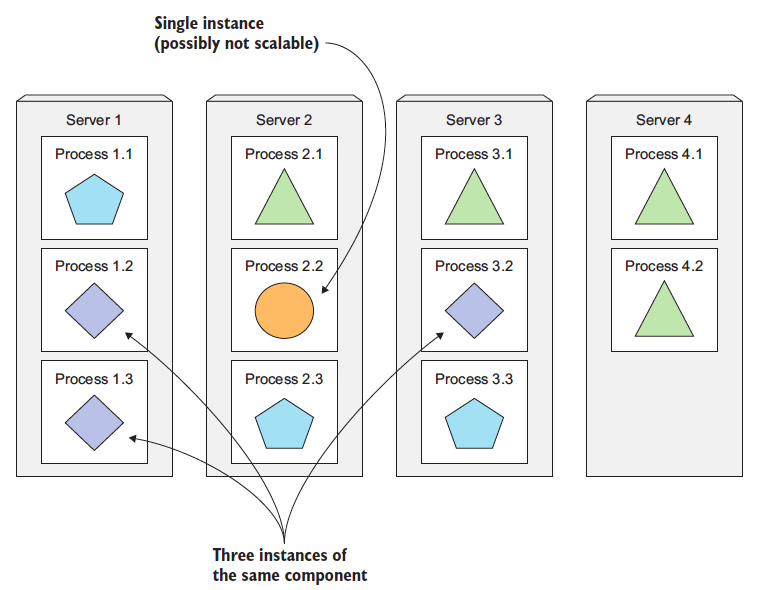

Scaling microservices, unlike monolithic systems, where you need to scale the system as a whole, is done on a per-service basis, which means you have the option of scaling only those services that require more resources, while leaving others at their original scale. Refer to image below

Image taken from other source

When a monolithic application can’t be scaled out because one of its parts is unscalable, splitting the app into microservices allows you to horizontally scale the parts that allow scaling out, and scale the parts that don’t, vertically instead of horizontally.

As always, microservices also have drawbacks. When your system consists of only a small number of deployable components, managing those components is easy. It’s trivial to decide where to deploy each component, because there aren’t that many choices. When the number of those components increases, deployment-related decisions become increasingly difficult because not only does the number of deployment combinations increase, but the number of inter-dependencies between the components increases by an even greater factor.

Microservices also bring other problems, such as making it hard to debug and trace execution calls, because they span multiple processes and machines. Luckily, these problems are now being addressed with distributed tracing systems such as Zipkin.

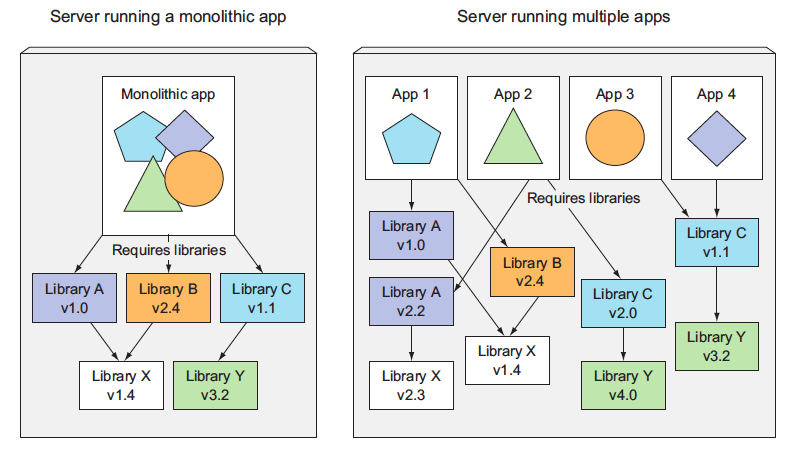

Multiple applications running on the same host may have conflicting dependencies.

Now that you have your app packaged inside a container image and made available through Docker Hub, you can deploy it in a Kubernetes cluster instead of running it in Docker directly. But first, you need to set up the cluster itself.

Setting up a full-fledged, multi-node Kubernetes cluster isn’t a simple task, especially if you’re not well-versed in Linux and networking administration. A proper Kubernetes install spans multiple physical or virtual machines and requires the networking to be set up properly so that all the containers running inside the Kubernetes cluster can connect to each other through the same flat networking space.

The simplest and quickest path to a fully functioning Kubernetes cluster is by using Minikube. Minikube is a tool that sets up a single-node cluster that’s great for both testing Kubernetes and developing apps locally.

Once you have Minikube installed locally, you can immediately start up the Kubernetes cluster with the command in the following listing.

minikube start

Starting local Kubernetes cluster...

Starting VM...

SSH-ing files into VM...

...

Kubectl is now configured to use the cluster.Starting the cluster takes more than a minute, so don’t interrupt the command before it completes.

To interact with Kubernetes, you also need the kubectl CLI client. Installing it is easy.

To verify your cluster is working, you can use the kubectl cluster-info command shown in the following listing.

kubectl cluster-info

Kubernetes master is running at https://192.168.99.100:8443

kubernetes-dashboard is running at https://192.168.99.100:8443/api/v1/...

KubeDNS is running at https://192.168.99.100:8443/api/v1/namespaces/kube-system/services/kube-dns:dns/proxyThis shows the cluster is up. It shows the URLs of the various Kubernetes components, including the API server and the web console.

The simplest way to deploy your app is to use the kubectl run command, which will create all the necessary components without having to deal with JSON or YAML.

kubectl run kubia --image=knrt10/kubia --port=8080 --generator=run/v1

The --image=knrt10/kubia part obviously specifies the container image you want to run, and the --port=8080 option tells Kubernetes that your app is listening on port 8080. The last flag (--generator) does require an explanation, though. Usually, you won’t use it, but you’re using it here so Kubernetes creates a ReplicationController instead of a Deployment.

Because you can’t list individual containers since they’re not standalone Kubernetes objects, can you list pods instead? Yes, you can. Let’s see how to tell kubectl to list pods in the following listing.

kubectl get pods

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kubia-5k788 1/1 Running 1 7dWith your pod running, how do you access it? Each pod gets its own IP address, but this address is internal to the cluster and isn’t accessible from outside of it. To make the pod accessible from the outside, you’ll expose it through a Service object. You’ll create a special service of type LoadBalancer because if you create a regular service (a ClusterIP service), as the pod, it would also only be accessible from inside the cluster. By creating a LoadBalancer-type service, an external load balancer will be created and you can connect to the pod through the load balancer’s public IP.

To create the service, you’ll tell Kubernetes to expose the ReplicationController you created earlier:

kubectl expose rc kubia --type=LoadBalancer --name kubia-http

service "kubia-http" exposed

Important: We’re using the abbreviation rc instead of replicationcontroller. Most resource types have an abbreviation like this so you don’t have to type the full name (for example, po for pods, svc for services, and so on).

The expose command’s output mentions a service called kubia-http. Services are objects like Pods and Nodes, so you can see the newly created Service object by running the kubectl get services | svc command, as shown in the following listing.

kubectl get svc

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 7d

kubia-http LoadBalancer 10.96.99.92 <pending> 8080:30126/TCP 7dImportant :- Minikube doesn’t support LoadBalancer services, so the service will never get an external IP. But you can access the service anyway through its external port. So external IP will always be pending in that case. When using Minikube, you can get the IP and port through which you can access the service by running

minikube service kubia-http

You now have a running application, monitored and kept running by a Replication-Controller and exposed to the world through a service. Now let’s make additional magic happen. One of the main benefits of using Kubernetes is the simplicity with which you can scale your deployments. Let’s see how easy it is to scale up the number of pods. You’ll increase the number of running instances to three.

Your pod is managed by a ReplicationController. Let’s see it with the kubectl get command:

kubectl get rc

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE

kubia 1 1 1 7dTo scale up the number of replicas of your pod, you need to change the desired replica count on the ReplicationController like this:

kubectl scale rc kubia --replicas=3

replicationcontroller "kubia" scaled

You’ve now told Kubernetes to make sure three instances of your pod are always running. Notice that you didn’t instruct Kubernetes what action to take. You didn’t tell it to add two more pods. You only set the new desired number of instances and let Kubernetes determine what actions it needs to take to achieve the requested state.

Back to your replica count increase. Let’s list the ReplicationControllers again to see the updated replica count:

kubectl get rc

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE

kubia 3 3 3 7dBecause the actual number of pods has already been increased to three (as evident from the CURRENT column), listing all the pods should now show three pods instead of one:

kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kubia-5k788 1/1 Running 1 7d

kubia-7zxwj 1/1 Running 1 3d

kubia-bsksp 1/1 Running 1 3dAs you can see, three pods exist instead of one. Currently running, but if it is pending, it would be ready in a few moments, as soon as the container image is downloaded and the container is started.

As you can see, scaling an application is incredibly simple. Once your app is running in production and a need to scale the app arises, you can add additional instances with a single command without having to install and run additional copies manually.

Keep in mind that the app itself needs to support being scaled horizontally. Kubernetes doesn’t magically make your app scalable; it only makes it trivial to scale the app up or down.

If you’ve been paying close attention, you probably noticed that the kubectl get pods command doesn’t even show any information about the nodes the pods are scheduled to. This is because it’s usually not an important piece of information.

But you can request additional columns to display using the -o wide option. When listing pods, this option shows the pod’s IP and the node the pod is running on:

kubectl get pods -o wide

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE

kubia-5k788 1/1 Running 1 7d 172.17.0.4 minikube

kubia-7zxwj 1/1 Running 1 3d 172.17.0.5 minikube

kubia-bsksp 1/1 Running 1 3d 172.17.0.6 minikubeTo open the dashboard in your browser when using Minikube to run your Kubernetes cluster, run the following command:

minikube dashboard

Pods and other Kubernetes resources are usually created by posting a JSON or YAML manifest to the Kubernetes REST API endpoint. Also, you can use other, simpler ways of creating resources, such as the kubectl run command, but they usually only allow you to configure a limited set of properties, not all. Additionally, defining all your Kubernetes objects from YAML files makes it possible to store them in a version control system, with all the benefits it brings.

You’ll use the kubectl get command with the -o yaml option to get the whole YAML definition of the pod, or you can use -o json to get the whole JSON definition as shown in the following listing.

kubectl get po kubia-bsksp -o yaml

The pod definition consists of a few parts. First, there’s the Kubernetes API version used in the YAML and the type of resource the YAML is describing. Then, three important sections are found in almost all Kubernetes resources:

- Metadata includes the name, namespace, labels, and other information about the pod.

- Spec contains the actual description of the pod’s contents, such as the pod’s containers, volumes, and other data.

- Status contains the current information about the running pod, such as what condition the pod is in, the description and status of each container, and the pod’s internal IP and other basic info.

The status part contains read-only runtime data that shows the state of the resource at a given moment. When creating a new pod, you never need to provide the status part.

The three parts described previously show the typical structure of a Kubernetes API object. All other objects have the same anatomy. This makes understanding new objects relatively easy.

Going through all the individual properties in the previous YAML doesn’t make much sense, so, instead, let’s see what the most basic YAML for creating a pod looks like.

You’re going to create a file called kubia-manual.yaml (you can create it in any directory you want), or copy from this repo, where you’ll find the file with filename kubia-manual.yaml. The following listing shows the entire contents of the file.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: kubia-manual

spec:

containers:

- image: knrt10/kubia

name: kubia

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

protocol: TCPLet’s examine this descriptor in detail. It conforms to the v1 version of the Kubernetes API. The type of resource you’re describing is a pod, with the name kubia-manual. The pod consists of a single container based on the knrt10/kubia image. You’ve also given a name to the container and indicated that it’s listening on port 8080.

To create the pod from your YAML file, use the kubectl create command:

kubectl create -f kubia-manual.yaml

pod/kubia-manual created

The kubectl create -f command is used for creating any resource (not only pods) from a YAML or JSON file.

Your little Node.js application logs to the process’s standard output. Containerized applications usually log to the standard output and standard error stream instead of writing their logs to files. This is to allow users to view logs of different applications in a simple, standard way.

To see your pod’s log (more precisely, the container’s log) you run the following command on your local machine (no need to ssh anywhere):

kubectl logs kubia-manual

Kubia server starting...

You haven’t sent any web requests to your Node.js app, so the log only shows a single log statement about the server starting up. As you can see, retrieving logs of an application running in Kubernetes is incredibly simple if the pod only contains a single container.

If your pod includes multiple containers, you have to explicitly specify the container name by including the -c container name option when running kubectl logs. In your kubia-manual pod, you set the container’s name to kubia, so if additional containers exist in the pod, you’d have to get its logs like this:

kubectl logs kubia-manual -c kubia

Note that you can only retrieve container logs of pods that are still in existence. When a pod is deleted, its logs are also deleted.

When you want to talk to a specific pod without going through a service (for debugging or other reasons), Kubernetes allows you to configure port forwarding to the pod. This is done through the kubectl port-forward command. The following command will forward your machine’s local port 8888 to port 8080 of your kubia-manual pod:

kubectl port-forward kubia-manual 8888:8080

In a different terminal, you can now use curl to send an HTTP request to your pod through the kubectl port-forward proxy running on localhost:8888:

curl localhost:8888

You've hit kubia-manual

Using port forwarding like this is an effective way to test an individual pod.

Organizing pods and all other Kubernetes objects is done through labels. Labels are a simple, yet incredibly powerful, Kubernetes feature for organizing not only pods, but all other Kubernetes resources. A label is an arbitrary key-value pair you attach to a resource, which is then utilized when selecting resources using label selectors (resources are filtered based on whether they include the label specified in the selector).

Now, you’ll see labels in action by creating a new pod with two labels. Create a new file called kubia-manual-with-labels.yaml with the contents of the following listing. You can also copy from kubia-manual-with-labels.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: kubia-manual-v2

labels:

creation_method: manual

env: prod

spec:

containers:

- image: knrt10/kubia

name: kubia

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

protocol: TCPYou’ve included the labels creation_method=manual and env=data.labels section. You’ll create this pod now:

kubectl create -f kubia-manual-with-labels.yaml

pod/kubia-manual-v2 created

The kubectl get po command doesn’t list any labels by default, but you can see them by using the --show-labels switch:

kubectl get po --show-labels

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE LABELS

kubia-5k788 1/1 Running 1 8d run=kubia

kubia-7zxwj 1/1 Running 1 5d run=kubia

kubia-bsksp 1/1 Running 1 5d run=kubia

kubia-manual 1/1 Running 0 7h <none>

kubia-manual-v2 1/1 Running 0 3m creation_method=manual,env=prodInstead of listing all labels, if you’re only interested in certain labels, you can specify them with the -L switch and have each displayed in its own column. List pods again and show the columns for the two labels you’ve attached to your kubia-manual-v2 pod:

kubectl get po -L creation_method,env

Labels can also be added to and modified on existing pods. Because the kubia-manual pod was also created manually, let’s add the creation_method=manual label to it:

kubectl label po kubia-manual creation_method=manual

Now, let’s also change the env=prod label to env=debug on the kubia-manual-v2 pod, to see how existing labels can be changed. You need to use the --overwrite option when changing existing labels.

kubectl label po kubia-manual-v2 env=debug --overwrite

Attaching labels to resources so you can see the labels next to each resource when listing them isn’t that interesting. But labels go hand in hand with label selectors. Label selectors allow you to select a subset of pods tagged with certain labels and perform an operation on those pods.

A label selector can select resources based on whether the resource

- Contains (or doesn’t contain) a label with a certain key

- Contains a label with a certain key and value

- Contains a label with a certain key, but with a value not equal to the one you specify

Let’s use label selectors on the pods you’ve created so far. To see all pods you created manually (you labeled them with creation_method=manual), do the following:

kubectl get po -l creation_method=manual

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kubia-manual 1/1 Running 0 22h

kubia-manual-v2 1/1 Running 0 14hAnd those that don’t have the env label:

kubectl get po -l '!env'

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kubia-5k788 1/1 Running 1 9d

kubia-7zxwj 1/1 Running 1 5d

kubia-bsksp 1/1 Running 1 5d

kubia-manual 1/1 Running 0 22hMake sure to use single quotes around !env, so the bash shell doesn’t evaluate the exclamation mark

A selector can also include multiple comma-separated criteria. Resources need to match all of them to match the selector. You can execute command given below

kubectl get po -l '!env , !creation_method' --show-labels

All the pods you’ve created so far have been scheduled pretty much randomly across your worker nodes. Certain cases exist, however, where you’ll want to have at least a little say in where a pod should be scheduled. A good example is when your hardware infrastructure isn’t homogenous. You never want to say specifically what node a pod should be scheduled to, because that would couple the application to the infrastructure, whereas the whole idea of Kubernetes is hiding the actual infrastructure from the apps that run on it.

The pods aren't only kubernetes resource type that you can attach label to. Labels can be attached to any Kubernetes resource including nodes.

Let’s imagine one of the nodes in your cluster contains a GPU meant to be used for general-purpose GPU computing. You want to add a label to the node showing this feature. You’re going to add the label gpu=true to one of your nodes (pick one out of the list returned by kubectl get nodes):

kubectl label node minikube gpu=true

node/minikube labeled

Now you can use a label selector when listing the nodes, like you did before with pods. List only nodes that include the label gpu=true:

kubectl get node -l gpu=true

NAME STATUS ROLES AGE VERSION

minikube Ready master 9d v1.10.0As expected, only one node has this label. You can also try listing all the nodes and tell kubectl to display an additional column showing the values of each node’s gpu label.

kubectl get nodes -L gpu

NAME STATUS ROLES AGE VERSION GPU

minikube Ready master 9d v1.10.0 trueNow imagine you want to deploy a new pod that needs a GPU to perform its work. To ask the scheduler to only choose among the nodes that provide a GPU, you’ll add a node selector to the pod’s YAML. Create a file called kubia-gpu.yaml with the following listing’s contents and then use kubectl create -f kubia-gpu.yaml to create the pod. The contents of file are

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: kubia-gpu

spec:

nodeSelector:

gpu: "true"

containers:

- image: luksa/kubia

name: kubiaYou’ve added a nodeSelector field under the spec section. When you create the pod, the scheduler will only choose among the nodes that contain the gpu=true label (which is only a single node in your case).

Similarly, you could also schedule a pod to an exact node, because each node also has a unique label with the key kubernetes.io/hostname and value set to the actual hostname of the node. Example shown below

kubectl get nodes --show-labels

NAME STATUS ROLES AGE VERSION LABELS

minikube Ready master 9d v1.10.0 beta.kubernetes.io/arch=amd64,beta.kubernetes.io/os=linux,gpu=true,kubernetes.io/hostname=minikube,node-role.kubernetes.io/master=But setting the nodeSelector to a specific node by the hostname label may lead to the pod being unschedulable if the node is offline.

In addition to other labels, pods and other objects can also contain annotations. They are also key value pairs, so in essence they are similar to labels, but aren't meant to hold identifying information. They can't be used to group objects the way label can. While objects can be selected through label selectors, there’s no such thing as an annotation selector. On the other hand, annotations can hold much larger pieces of information and are primarily meant to be used by tools. Certain annotations are automatically added to objects by Kubernetes, but others are added by users manually.

A great use to annotating pods is to add desciption to each pod or other API object so that everyone using the cluster can quickly look up information about each individual object.

Let’s see an example of an annotation that Kubernetes added automatically to the pod you created in the previous section. To see the annotations, you’ll need to request the full YAML of the pod or use the kubectl describe command. You’ll use the first option in the following listing.

kubectl get po kubia-zb95q -o yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

annotations:

kubernetes.io/created-by: |

{"kind":"SerializedReference", "apiVersion":"v1",

"reference":{"kind":"ReplicationController", "namespace":"default", ...Without going into too many details, as you can see, the kubernetes.io/created-by

annotation holds JSON data about the object that created the pod. That’s not something

you’d want to put into a label. Labels should be short, whereas annotations can

contain relatively large blobs of data (up to 256 KB in total).

Important:- The kubernetes.io/created-by annotations was deprecated in version

1.8 and will be removed in 1.9, so you will no longer see it in the YAML.

Annotations can obviously be added to pods at creation time, the same way label can. But we can also add it after using the following command. Let's try adding this to kubia-manual pod now.

kubectl annotate pod kubia-manual knrt10.github.io/someannotation="messi ronaldo"

You added the annotation knrt10.github.io/someannotation with the value messi ronaldo. It’s a good idea to use this format for annotation keys to prevent key collisions. When different tools or libraries add annotations to objects, they may accidentally override each other’s annotations if they don’t use unique prefixes like you did here. You can check your pod now using following command

kubectl describe po kubia-manual

Previously we saw how labels organize pods and objects into groups. Because each object can have multiple labels, those groups of objects can overlap. Plus, when working with the cluster (through kubectl for example), if you don’t explicitly specify a label selector, you’ll always see all objects.

Let us first list all the namespaces in our cluster, type the following command

kubectl get ns

NAME STATUS AGE

default Active 9h

kube-public Active 9h

kube-system Active 9hUp to this point, you’ve operated only in the default namespace. When listing resources with the kubectl get command, you’ve never specified the namespace explicitly, so kubectl always defaulted to the default namespace, showing you only the objects in that namespace. But as you can see from the list, the kube-public and the kube-system namespaces also exist. Let’s look at the pods that belong to the kube-system namespace, by telling kubectl to list pods in that namespace only:

kubectl get po -n kube-system

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

etcd-minikube 1/1 Running 0 4h

kube-addon-manager-minikube 1/1 Running 1 9h

kube-apiserver-minikube 1/1 Running 0 4h

kube-controller-manager-minikube 1/1 Running 0 4h

kube-dns-86f4d74b45-w8mqv 3/3 Running 4 9h

kube-proxy-25t92 1/1 Running 0 4h

kube-scheduler-minikube 1/1 Running 0 4h

kubernetes-dashboard-5498ccf677-2zcw5 1/1 Running 2 9h

storage-provisioner 1/1 Running 2 9hI will explain about these pods later (don’t worry if the pods shown here don’t match the ones on your system exactly). It’s clear from the name of the namespace that these are resources related to the Kubernetes system itself. By having them in this separate namespace, it keeps everything nicely organized. If they were all in the default namespace, mixed in with the resources you create yourself, you’d have a hard time seeing what belongs where, and you might inadvertently delete system resources.

Namespaces enable you to separate resources that don’t belong together into nonoverlapping groups. If several users or groups of users are using the same Kubernetes cluster, and they each manage their own distinct set of resources, they should each use their own namespace. This way, they don’t need to take any special care not to inadvertently modify or delete the other users’ resources and don’t need to concern themselves with name conflicts, because namespaces provide a scope for resource names, as has already been mentioned.

A namespace is a Kubernetes resource like any other, so you can create it by posting a YAML file to the Kubernetes API server. Let’s see how to do this now.

You’re going to create a file called custom-namespace.yml (you can create it in any directory you want), or copy from this repo, where you’ll find the file with filename custom-namespace.yml. The following listing shows the entire contents of the file.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Namespace

metadata:

name: custom-namespaceNow type the following command

kubectl create -f custom-namespace.yaml

namespace/custom-namespace created

To create resources in the namespace you’ve created, either add a namespace: customnamespace entry to the metadata section, or specify the namespace when creating the resource with the kubectl create command:

kubectl create -f kubia-manual.yaml -n custom-namespace

pod/kubia-manual created

You now have two pods with the same name (kubia-manual). One is in the default

namespace, and the other is in your custom-namespace.

When listing, describing, modifying, or deleting objects in other namespaces, you

need to pass the --namespace (or -n) flag to kubectl. If you don’t specify the namespace, kubectl performs the action in the default namespace configured in the current kubectl context. The current context’s namespace and the current context itself can be changed through kubectl config commands.

To wrap up this section about namespaces, let me explain what namespaces don’t provide at least not out of the box. Although namespaces allow you to isolate objects into distinct groups, which allows you to operate only on those belonging to the specified namespace, they don’t provide any kind of isolation of running objects. For example, you may think that when different users deploy pods across different namespaces, those pods are isolated from each other and can’t communicate but that’s not necessarily the case. Whether namespaces provide network isolation depends on which networking solution is deployed with Kubernetes. When the solution doesn’t provide inter-namespace network isolation, if a pod in namespace foo knows the IP address of a pod in namespace bar, there is nothing preventing it from sending traffic, such as HTTP requests, to the other pod.

We have created a number of pods which should all be running. If you have followed from the start, you should have 5 pods in default namespace and one in custom-namespace. We are going to stop them all now, because we don't need them anymore.

Let's first delele kubia-gpu pod name

kubectl delete po kubia-gpu

Instead of specifying each pod to delete by name, you’ll now use what you’ve learned

about label selectors to stop both the kubia-manual and the kubia-manual-v2 pod.

Both pods include the creation_method=manual label, so you can delete them by

using a label selector:

kubectl delete po -l creation_method=manual

pod "kubia-manual" deleted pod "kubia-manual-v2" deleted

In the earlier microservices example, where you had tens (or possibly hundreds) of

pods, you could, for instance, delete all canary pods at once by specifying the

rel=canary label selector

kubectl delete po -l rel=canary

Okay, back to your real pods. What about the pod in the custom-namespace? We no

longer need either the pods in that namespace, or the namespace itself. You can delete the whole namespace using the following command. Your all pods inside that workspace will be automatically deleted.

kubectl delete ns custom-namespace

namespace "custom-namespace" deleted

Suppose you want to keep your namespace but delete all the pods in it, so this is the approach to follow. We now have cleaned almost everything but we have some pods running if you ran the kubectl run command before.

This time, instead of deleting the specific pod, tell Kubernetes to delete all pods in the current namespace by using the --all option

kubeclt delete po --all

pod "kubia-pjxrs" deleted

pod "kubia-xvfxp" deleted

pod "kubia-zb95q" deletedNow, double check that no pods were left running:

kubectl get po

kubia-5gknm 1/1 Running 0 48s

kubia-h62k7 1/1 Running 0 48s

kubia-x4nsb 1/1 Running 0 48sWait, what!?! All pods are terminating, but a new pod which weren't there before, has appeared. No matter how many times you delete all pods, a new pod called kubia-something will emerge.

You may remember you created your first pod with the kubectl run command. I mentioned that this doesn’t create a pod directly, but instead creates a ReplicationController, which then creates the pod. As soon as you delete a pod created by the ReplicationController, it immediately creates a new one. To delete the pod, you also need to delete the ReplicationController.

You can delete the ReplicationController and the pods, as well as all the Services you’ve created, by deleting all resources in the current namespace with a single command:

kubectl delete all --all

pod "kubia-5gknm" deleted

pod "kubia-h62k7" deleted

pod "kubia-x4nsb" deleted

replicationcontroller "kubia" deleted

service "kubernetes" deleted

service "kubia-http" deletedThe first all in the command specifies that you’re deleting resources of all types, and the --all option specifies that you’re deleting all resource instances instead of specifying them by name (you already used this option when you ran the previous delete command).

As it deletes resources, kubectl will print the name of every resource it deletes. In the list, you should see the kubia ReplicationController and the kubia-http Service you created before.

Note:- The kubectl delete all --all command also deletes the kubernetes Service, but it should be recreated automatically in a few moments.

As far now, you might have understood that pods represent the basic deployment unit in Kubernetes. We know how to create, supervise and manage them manually. But in real-world use cases, you want your deployments to stay up and running automatically and remain healthy without any manual intervention. To do this, we never almost create pods directly. Instead we create other type of resources like ReplicationControllers or Deployments which then create and manage the actual pods.

When you create unmanaged pods (such as the ones we created previously), a cluster node is selected to run the pod and then its containers are run on that node. Now, we'll learn that Kubernetes then monitors those containers and automatically restarts them if they fail. But if the whole node fails, the pods on the node are lost and will not be replaced with new ones, unless those pods are managed by the previously mentioned ReplicationControllers or similar.

We'll now learn how Kubernetes checks if a container is still alive and restarts it if it isn’t. We’ll also learn how to run managed pods—both those that run indefinitely and those that perform a single task and then stop.

One of the main benefits of using Kubernetes is the ability to give it a list of containers and let it keep those containers running somewhere in the cluster. You do this by creating a Pod resource and letting Kubernetes pick a worker node for it and run the pod’s containers on that node. But what if one of those containers dies?What if all containers of a pod die?

As soon as a pod is scheduled to a node, the Kubelet on that node will run its containers and, from then on, keep them running as long as the pod exists. If the container’s main process crashes, the Kubelet will restart the container. If your application has a bug that causes it to crash every once in a while, Kubernetes will restart it automatically, so even without doing anything special in the app itself, running the app in Kubernetes automatically gives it the ability to heal itself.

But sometimes apps stop working without their process crashing. For example, a Java app with a memory leak will start throwing OutOfMemoryErrors, but the JVM process will keep running. It would be great to have a way for an app to signal to Kubernetes that it’s no longer functioning properly and have Kubernetes restart it.

We’ve said that a container that crashes is restarted automatically, so maybe you’re thinking you could catch these types of errors in the app and exit the process when they occur. You can certainly do that, but it still doesn’t solve all your problems.

For example, what about those situations when your app stops responding because it falls into an infinite loop or a deadlock? To make sure applications are restarted in such cases, you must check an application’s health from the outside and not depend on the app doing it internally.

Kubernetes can check if a container is still alive through liveness probes. You can specify a liveness probe for each container in the pod's specification. Kubernetes can probe the container using one of three mechanisms:

-

An

HTTP GETprobe performs an HTTP GET request on the container's IP address, a port and path you specify. If the probe receives a response and the response code doesn’t represent an error (in other words, if the HTTP response code is 2xx or 3xx), the probe is considered successful. If the server returns an error response code or if it doesn’t respond at all, the probe is considered a failure and the container will be restarted as a result. -

A

TCP Socketprobe tries to open a TCP connection to the specified port of the container. If the connection is established successfully, the probe is successful. Otherwise, the container is restarted. -

An

Execprobe executes an arbitrary command inside the container and checks the command’s exit status code. If the status code is 0, the probe is successful. All other probes are considered as failure.

Let’s see how to add a liveness probe to your Node.js app. Because it’s a web app, it makes sense to add a liveness probe that will check whether its web server is serving requests. But because this particular Node.js app is too simple to ever fail, you’ll need to make the app fail artificially.

To properly demo liveness probes, you’ll modify the app slightly and make it return a 500 Internal Server Error HTTP status code for each request after the fifth one—your app will handle the first five client requests properly and then return an error on every subsequent request. Thanks to the liveness probe, it should be restarted when that happens, allowing it to properly handle client requests again.

I’ve pushed the container image to Docker Hub, so you don’t need to build it yourself. If you want you can see folder kubia-unhealthy for more information. You’ll create a new pod that includes an HTTP GET liveness probe. The following listing shows the YAML for the pod.

You’re going to create a file called kubia-liveness-probe.yaml (you can create it in any directory you want), or copy from this repo, where you’ll find the file with filename kubia-liveness-probe.yaml. The following listing shows the entire contents of the file.

apiVersion: v1

kind: pod

metadata:

name: kubia-liveness

spec:

containers:

- image: knrt10/kubia-unhealthy

name: kubia

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /

port: 8080The pod descriptor defines an httpGet liveness probe, which tells Kubernetes to periodically perform HTTP GET requests on path / on port 8080 to determine if the container is still healthy. These requests start as soon as the container is run.

After five such requests (or actual client requests), your app starts returning HTTP status code 500, which Kubernetes will treat as a probe failure, and will thus restart the container.

To see what a liveness probe does, try creating a pod now. After about a minute and a half, the container will be restarted. You can see that by running kubectl get

kubectl get po kubia-liveness

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kubia-liveness 1/1 Running 1 2m- Write more about pods

- Write about yaml files

- Write about ingress routing

- Write about volumes

- Write about config maps and secrets

- Write more on updating running pods

- Write about StatefulSets

- More on securing pods and containers

- Implement && write about GCP