A Bite of Python,也可叫作“咬一口Python”,寓意着Python的冰山一角,包含着作者这几年学Python时积累的一些知识和经验,文章中包含了许多快速简洁的例子,方便让读者了解到Python中存在的一些概念,然后去自行拓展。

Python是一门解释型的高级编程语言,由Guido van Rossum于1989年开始编写,并在1991年发布了第一版。Python的特点是代码简洁而且可读性强,使用空格缩进来划分代码块。

用浏览器访问官网的下载页面Download Python,选择合适的版本下载安装。

命令行安装:

Mac:

$ brew install python3Debian&Ubuntu:

$ sudo apt-get install python3Python的官方解释器是CPython,也就是我们通常讨论的Python的实现,它是用C编写的,负责将编写好的Python代码翻译并执行。

除此之外,Python还有许多实现版本:

- PyPy,用rPython实现的Python解释器,使用了JIT编译技术,因此执行速度通常比C实现的CPython还要快。

- Jython,一个用Java实现的Python解释器。

- IronPython,一个用.NET实现的Python解释器。

不同于一些语言使用花括号的方式来明确代码块,Python用缩进来表示代码的层级(通常是四个空格,最好不要用tab)

x = 75

if x >= 60:

if x > 80:

print('A')

else:

print('B')

else:

print('C')

# 75| 运算 | 结果 |

|---|---|

x or y |

如果 x 是false, 就是y, 否则是 x |

x and y |

如果 x 是false, 就是x, 否则是 y |

not x |

如果 x 是false, 就是True, 否则是 False |

| 运算 | 含义 |

|---|---|

< |

小于 |

<= |

小于或等于 |

> |

大于 |

>= |

大于等于 |

== |

等于 |

!= |

不等于 |

is |

对象标识等于 |

is not |

对象标识不等于 |

| 运算 | 含义 |

|---|---|

x + y |

加法 |

x - y |

减法 |

x * y |

乘法 |

x / y |

除法 |

x // y |

整除 |

x % y |

取模 |

-x |

取反 |

+x |

取正 |

abs(x) |

绝对值 |

int(x) |

整型转换 |

float(x) |

浮点数转换 |

complex(re, im) |

复数 |

c.conjugate() |

共轭复数 |

divmod(x, y) |

返回(x // y, x % y) |

pow(x, y) |

x的y次幂 |

x ** y |

x的y次幂 |

| 运算 | 含义 |

|---|---|

| `x | y` |

x ^ y |

按位异或 |

x & y |

按位与 |

x << n |

按位左移 |

x >> n |

按位右移 |

~x |

按位反转 |

True和False分别表示Python布尔值中的真和假,当用==比较时,1与True相等,0与False相等,因此True和False还可以当作索引应用在容器操作上。

用内置的bool函数可以返回一个对象的布尔值表示,通常一个空的容器(例如一个空列表、一个空字典)的布尔值表示会返回False,反之为True,此外None的布尔值表示也是为False。

type(False), type(True)

# <class 'bool'> <class 'bool'>

0 == False, 1 == True

# True True

0 is False, 1 is True

# False False

[1,2,3][False], [1,2,3][True]

# 1 2

bool([]), bool({}), bool(set()), bool(()), bool(''), bool(None)

# False False False False False FalseNone在Python中表示空或不存在的含义,在同一个运行的程序中,None的地址只有一个。

当一个函数没有执行return语句或者执行一个没有返回对象的return语句时,默认会返回None值。

type(None)

# <class 'NoneType'>

id(None) == id(None)

# True

def f():

a = 1

def f2():

a = 1

return

f()

# None

f2()

# Nonenot在Python中常用于逻辑判断,表示非或不的含义,当not应用在布尔值时,会把布尔值取反返回,否则会尝试将对象转成布尔值表示再进行逻辑操作。

not False

not True

not None

not [], not {}, not (), not set()

# True

# False

# True

# True True True Truenot一般也应用于判断一个对象是否存在于容器上:

1 not in (1, 2, 3)

# False

1 not in [1, 2, 3]

# False

'a' not in {'a': 1}

# False

'a' not in {'a', 'b'}还有用于对象的标识判断:

a = 'None'

a is not None

# Trueis用于判断是否同一个对象:

True is True

True is not True

# True

# False

sentinel = object()

l = []

l.append(object())

l.append(sentinel)

l.append(object())

for obj in sentinel

print('object')

if obj is sentinel:

break

# objectA simple life lesson:

import this

# ...

love = this

this is love

# True

love is True

# False

love is False

# False

love is not True or False

# True

love is not True or False; love is love

# Trueand表示与的关系,用在条件表达式时,表示只有两个条件同时成立的情况下,判断条件才成功。

True and False

True and True

False and False

False and True

# False

# True

# False

# False当用and来连接两个表达式时,根据短路性质,如果第一个表达式的布尔表示为False,那么不会计算后面的表达式。

def condition_true():

print("true")

return True

def condition_false():

print("false")

return False

if condition_true() and condition_false():

pass

# true

# false

if condition_false() and condition_true():

pass

# false

if condition_true() and condition_true():

pass

# true

# trueor表示或的关系,用在条件表达式时,表示如果有其中一个条件成立的情况下,则判断条件成功。

True or False

True or True

False or False

False or True

# True

# True

# False

# True当用or来连接两个表达式时,根据短路性质,如果第一个表达式的布尔表示为True,那么不会计算后面的表达式。

def condition_true():

print("true")

return True

def condition_false():

print("false")

return False

if condition_true() or condition_false():

pass

# true

if condition_false() or condition_true():

pass

# false

# true

if condition_true() or condition_true():

pass

# true

None or []

None or [] or {}

None or [] or {}

# []

# {}def用于定义一个函数或方法,后面跟着的是函数名,以及参数列表。

def f():

print("f")

f()

# f

def f():

print("f")

def f2():

print("f2")

return f2

f2 = f()

f2()

# f

# f2在定义类的实例方法时,函数参数列表的第一个参数代表着类实例本身:

class Func:

def f(self):

print("f")

return self.f2

def f2(self):

print("f2")

f2 = Func().f()

f2()

# f

# f2pass在Python中不做任何事情,通常用pass是为了保持程序结构的完整性,例如提前定义一个稍后实现的函数,或者继承一个基类但不重写其中的方法(常见于自定义异常)等等。

def f():

pass

class MyException(Exception):

passimport语句在Python中的作用是导入其他模块,籍此访问其他模块中的变量。

import sys

sys.version_info

# sys.version_info(major=3, minor=6, micro=1, releaselevel='final', serial=0)导入又分为绝对导入和相对导入,其中import <>属于绝对导入,相对导入一般用from <> import的方式。

from语句用来从一个模块中导入变量。

from sys import version_info

version_info

# sys.version_info(major=3, minor=6, micro=1, releaselevel='final', serial=0)相对导入一般可以用from <> import的语法来完成,在PEP 328中有一个例子,假设当前的目录结构如下:

package/

__init__.py

subpackage1/

__init__.py

moduleX.py

moduleY.py

subpackage2/

__init__.py

moduleZ.py

moduleA.py

而当前文件是moduleX.py或者subpackage1/__init__.py,以下的相对导入的语法都是合法的:

from .moduleY import spam

from .moduleY import spam as ham

from . import moduleY

from ..subpackage1 import moduleY

from ..subpackage2.moduleZ import eggs

from ..moduleA import foo

from ...package import bar在导入模块时可以给模块起别名,而这个操作一般可以用as关键字来实现:

import abc as cba

cba

# <module 'abc' from '/usr/local/Cellar/python3/3.6.1/bin/../Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.6/lib/python3.6/abc.py'>assert语句用于实现表达式的断言,如果断言没有通过,则会抛出一个AsserationError异常:

assert 1+1 == 2

assert 1+1 == 3, "1+1=2!"

# AssertionError: 1+1=2!for语句用于对一个可迭代对象执行遍历操作,需与in配合使用。

for i in range(3):

print(i)

# 0

# 1

# 2

for i in "abc":

print(i)

# a

# b

# c

[i for i in reversed("abc")]

# ['c', 'b', 'a']break用于中断当前循环体的执行,跳出当前循环。

while True:

print(1)

break

print(2)

# 1

for i in range(5):

if i == 3:

break

print(i)

# 0

# 1

# 2continue用于跳过当前的循环体的一个迭代。

for i in range(5):

if i == 3:

continue

print(i)

# 0

# 1

# 2

# 4class用于类的定义。

class Counter:

base = 0

def __init__(self):

self.c = self.base

def add(self, i):

self.c += i

return self.c

c = Counter()

c.add(1)

c.add(1)

Counter.base = 5

c.add(1)

Counter().add(1)

# 1

# 2

# 3

# 6在类层级定义的属性或者方法都会绑定到类的__dict__属性上,而每个实例则有自身的__dict__属性,存放实例的属性。

__dict__属性是一个字典,键为变量的名称,值则是对于的变量值。

Counter.__dict__

# mappingproxy({'__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Counter' objects>,

# '__doc__': None,

# '__init__': <function __main__.Counter.__init__>,

# '__module__': '__main__',

# '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Counter' objects>,

# 'add': <function __main__.Counter.add>,

# 'base': 0})

Counter().__dict__

# {'c': 0}

vars(Counter()) # 等于 Counter().__dict__

# {'c': 0}del语句用来删除一个变量的引用,也可以用于容器上的删除操作。

在这个例子中,当执行del a操作后,下面的print(a)语句就会因为无法访问到a这个变量而抛出异常了。

a = 1

del a

try:

print(a)

except NameError:

print("no variable named a!")

# no variable named a!除此之外,del也可以用于容器元素或对象属性的删除操作。

l = [1, 2, 3]

del l[1]

l

# [1, 3]

a = {

"a": 1,

"b": 2

}

del a["a"]

"a" in a

# False

class MyClass:

def __init__(self):

self.i = 1

my_class = MyClass()

hasattr(my_class, "i")

# True

del my_class.i

hasattr(my_class, "i")

# Falseif,elif和else关键字组成程序中的条件语句和控制流。

for i in [1, 2, 3]:

if i == 3:

print("if")

elif i == 2:

print("elif")

else:

print("else")

# else

# elif

# iftry,raise,except和finally关键字用于处理和控制程序的异常。

for i in [-1, 0, 1]:

try:

if i == -1:

raise ValueError

if i == 0:

raise Exception

except ValueError:

print("ValueError")

except Exception:

print("Exception")

finally:

print("i=", i)

# ValueError

# i= -1

# Exception

# i= 0

# i= 1lambda语句用于定义一个匿名函数,函数内容为单个表达式,表达式的值就是lambda函数的返回值。

add = lambda a, b: a+b

add(1,2)

# 3

class ObjectFactory:

create = lambda : object()

ObjectFactory.create()

# <object object at 0x108074100>当一个函数中出现了yield关键字时,这个函数就变成了一个生成器,调用这个函数时会返回一个generator对象,接下来可以用next函数来驱动这个生成器往下执行,直至碰到一个yield语句,这时候生成器会返回函数yield语句后面的对象,也可以调用生成器的send方法给生成器发送一个值,这个发送的值会成为yield语句的返回值,当生成器执行完最后一个yield语句后,此时继续驱动生成器就会抛出一个StopIteration的异常,生成器的return语句的返回值会赋值给这个异常实例的value属性上。

def g():

a = yield 1

b = yield a

yield b

return "done"

g = g()

g

# <generator object g at 0x101d4c990>

next(g) # equals to `g.send(None)`, variable a will become a `None`

# 1

g.send(2)

# 2

next(g)

# None

try:

next(g)

except StopIteration as e:

print(e.value)

# done如果函数内想对一个全局作用域的变量进行赋值时,则需要用global关键字来声明你想要接触的变量名,接下来便可以访问和修改这个变量。

a = 1

def g():

global a

a = 2

a

g()

a

# 1

# 2要理解nonlocal关键字,可以看以下的例子。

在这个例子中,内层函数inside想要修改外层函数变量a的值,但执行outside函数后返回的结果为1。

def outside():

a = 1

def inside():

a = 2

inside()

return a

outside()

# 1原因是在执行inside函数时的a = 2语句时,程序认为a是inside函数中的一个局部变量,因此外层函数的变量a没有受到影响。

解决方法是在a = 2语句之前用nonlocal来声明a不是一个局部变量,这样inside在执行时就会去外层函数寻找名称为a的变量,并对这个值进行修改。

def outside():

a = 1

def inside():

nonlocal a

a = 2

inside()

return a

outside()

# 2with语句需要配合上下文管理器来使用,上下文管理器是一个定义了进入和离开操作的对象,当执行到with语句时,程序就会触发跟随with语句后面的上下文管理器的进入回调,当离开with包裹的区块后,程序就会触发上下文管理器的离开回调。

这常见于一些资源获取和资源释放的动作,例如下面是一个打开文件的例子,当不用with语句时,需要手动控制文件的关闭,而用with的话,即保证了代码的整洁的同时也确保了可读性。

f = open("/etc/hosts")

f.readline()

f.close()

with open("/etc/hosts") as f:

f.readline()想定义一个上下文管理器十分简单,只需要编写一个类,并定义其中的__enter__(对应进入)和__exit__(对应离开)方法就可以了。

class Context:

def __enter__(self):

print("__enter__")

return self

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb):

print("__exit__")

with Context() as ctx:

ctx

# __enter__

# <__main__.Context object at 0x10dab5438>

# __exit__定义注释有两种方式,一种是以"#"开头,这种属于是单行注释,另一种是用三个引号包裹字符串,这种可以用作多行注释,也有一种用法是定义函数或类的文档字符串。

'''

multiple

lines

comment

'''

a = 1

# single line comment

b = 2

class C:

''' This is doc-string

'''

pass

print(repr(C.__doc__))

#' This is doc-string\n '要理解Python中的变量首先要明白Python中的命名空间。在Python中,命名空间本质上就是名字到对象的一个映射,因此我们平时谈论的变量也是由名字以及对象两个部分来组成,当执行a = 1这条语句时,Python会在命名空间中添加a这个名字,并把这个名字绑定到1上面,当执行print(a)这条语句时,Python则会从命名空间中查找a这个名字,再把这个名字映射的对象取出来完成后面的动作。

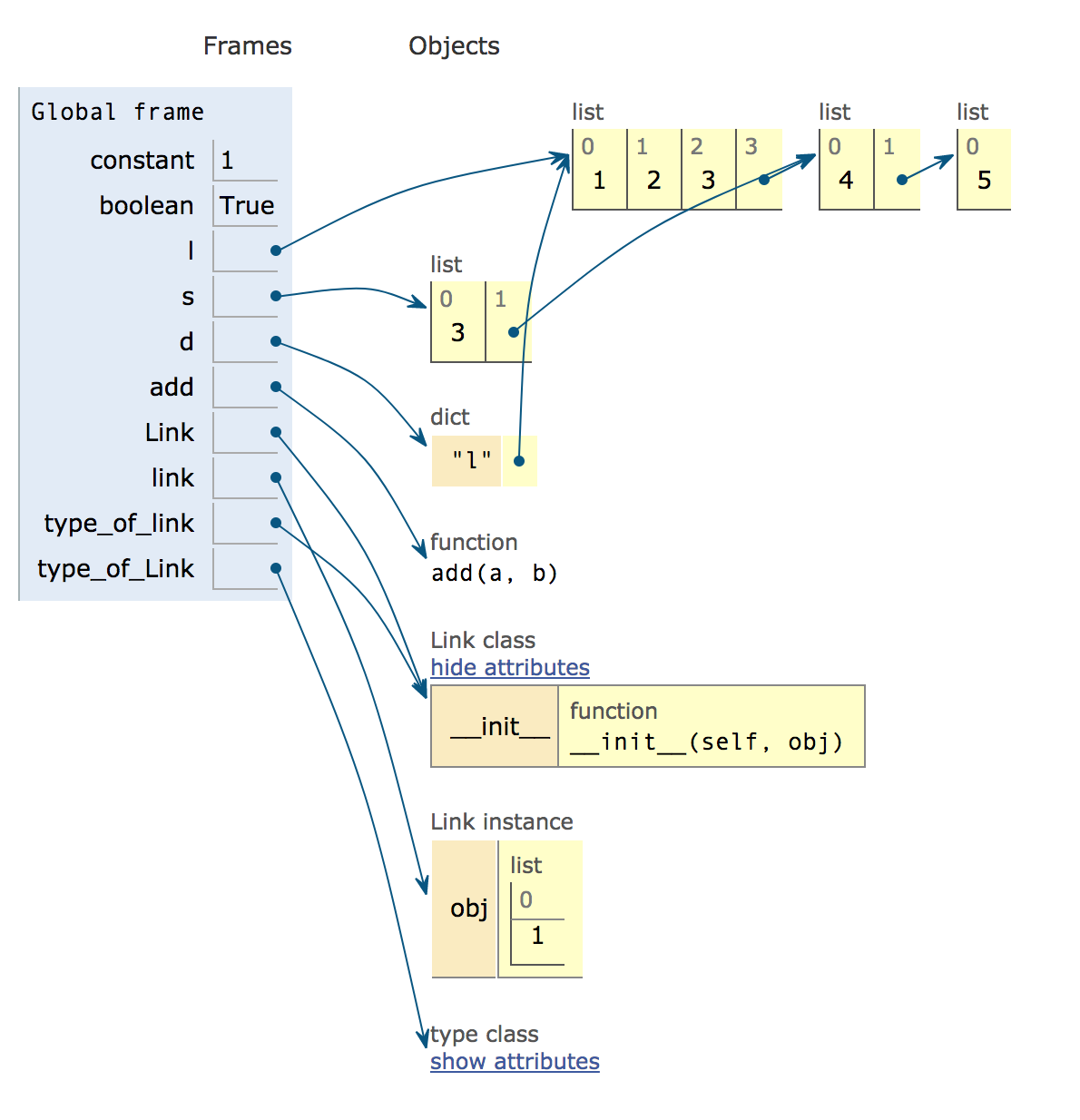

例如下面这个例子中就很好的展示了Python的对象是如何组织起来的:

constant = 1

boolean = True

l = [1,2,3, [4, [5]]]

s = l[2:]

d = {"l": l}

def add(a, b):

return a + b

add(1,2)

class Link:

def __init__(self, obj):

self.obj = obj

link = Link([1])

type_of_link = type(link)

type_of_Link = type(Link)在Python中万物皆对象,所有的类都继承自object类。

isinstance(1, object)

# True

isinstance('1', object)

# True

isinstance([1], object)

# True

class A: pass

isinstance(A, object)

# True

isinstance(object, object)

# True

isinstance(object(), object)

# True用type函数能获取对象的类型,例如一个列表的类型是list,类A的实例的类型是__main__.A类,而这个类的类型是type,反而言之,类是type的一个实例。

type([])

# list

type(A())

# __main__.A

type(type(A()))

# type再来看一下看似奇怪的例子:

isinstance(type, object)

# True

isinstance(object, type)

# True通过上面这个例子可以看到,type是一个object,object又是一个type,这是什么回事呢?

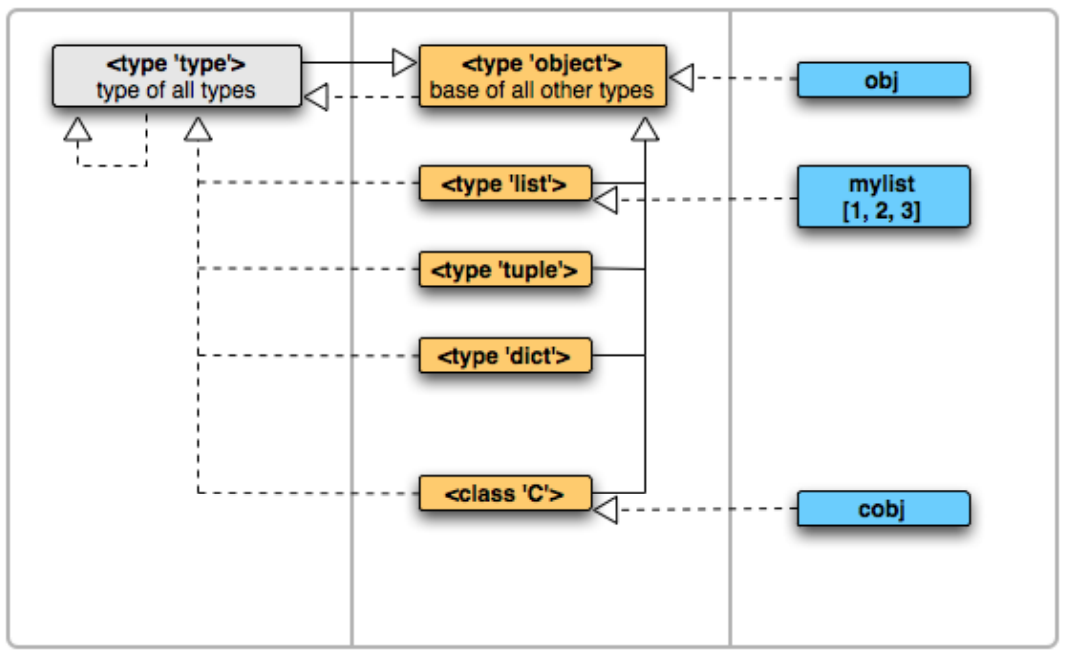

其实,type和object有点类似先有鸡还是先有蛋的情况,通过下面这个例子和图解,便能很好的理解type和object之间的关系。首先万物皆object,而type也是继承自object的,但object是type的一个实例,假如我们编写了一个列表,那么这个列表实际上是list的一个实例,list继承了object,而list和object都属于type的实例,这种创造类的类我们也一般称它为元类(metaclasses)。

obj = object()

cobj = C()

mylist = [1,2,3] 再来一个例子表明它们之间的关系:

issubclass(type, object) # type继承了object

# True

issubclass(object, type)

# False

isinstance(object, type) # object是type的一个实例

# True

isinstance(type, object) # 因为type继承了object,所以这里为True

# TruePython代码是如何一步步地转化成Python虚拟机所能理解的形式呢?简单地说,从Python代码转换成字节码的过程中会经过以下的几个过程:

- 把Python源码转换成解析树。

- 把解析树转换成抽象语法树(AST)。

- 生成符号表。

- 从AST中生成codeobject:

- 把AST转换为控制流

- 从控制流中提交codeobject

Python中有个内置的compile函数,可以将源代码转换成codeobject,codeobject中包含了源代码转译后的字节码。

compile(source, filename, mode, flags=0, dont_inherit=False, optimize=-1)其中flags指明了编译的特征,例如ast模块的parse函数就把flags设置为PyCF_ONLY_AST。

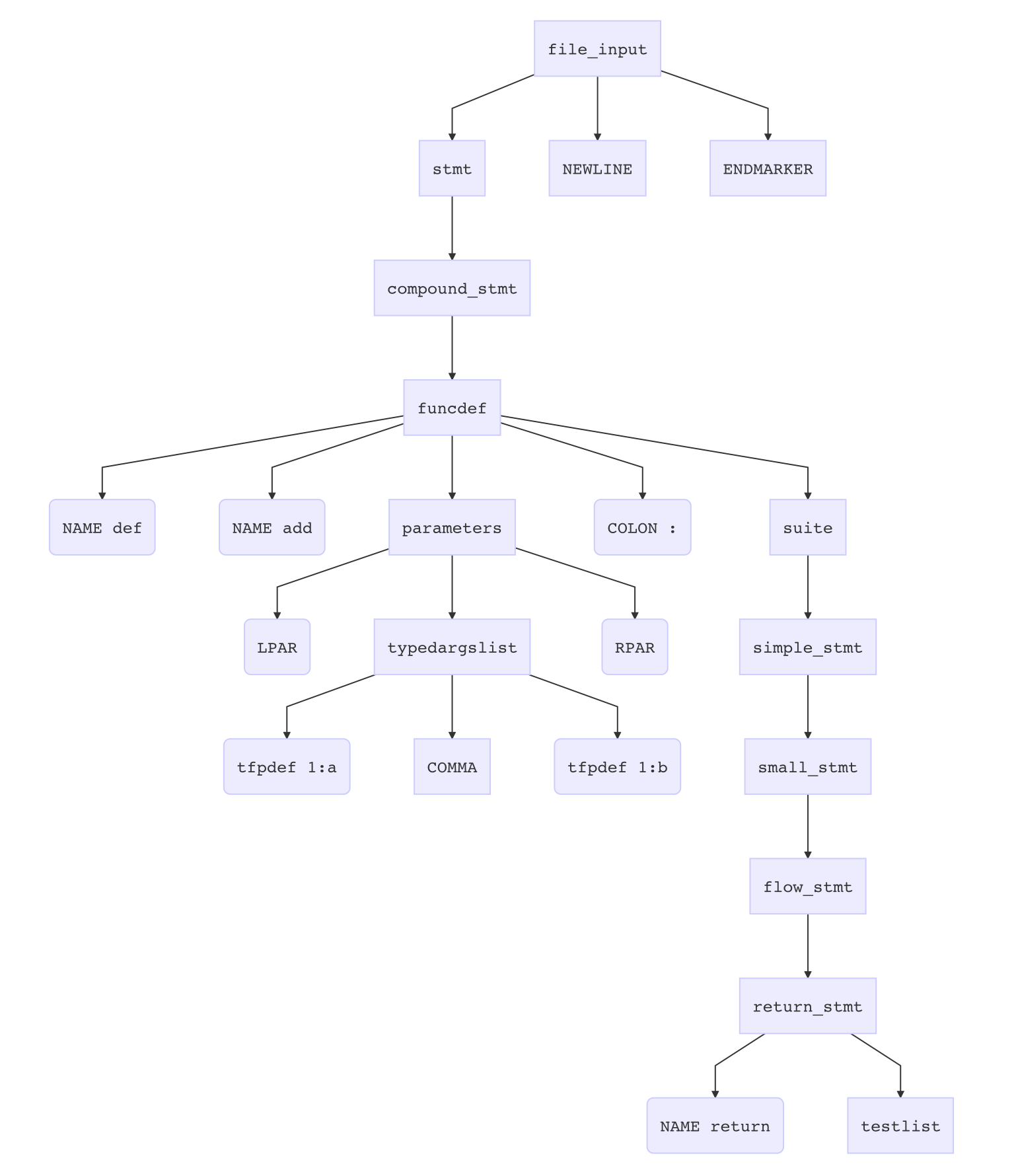

compile(source, filename, mode, PyCF_ONLY_AST)前面说了Python在执行时会把代码转化为解析树,那么解析树长什么样呢?

下面用parser模块对一个加法函数就行解析,对结果进行打印:

import parser

from pprint import pprint

code_str = 'def add(a, b):return a + b'

res = parser.suite(code_str)

pprint(res.tolist())不难看出,这个结果列表是一个树状结构:

[257,

[269,

[295,

[263,

[1, 'def'],

[1, 'add'],

[264,

[7, '('],

[265, [266, [1, 'a']], [12, ','], [266, [1, 'b']]],

[8, ')']],

[11, ':'],

[304,

[270,

[271,

[278,

[281,

[1, 'return'],

[331,

[305,

[309,

[310,

[311,

[312,

[315,

[316,

[317,

[318,

[319,

[320, [321, [322, [323, [324, [1, 'a']]]]]],

[14, '+'],

[320, [321, [322, [323, [324, [1, 'b']]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]],

[4, '']]]]]],

[4, ''],

[0, '']]

但列表里面大部分都是让人看不懂的数字,其实每个数字都代表了一个符号或者令牌,分别象征着不同的含义,它们对应的含义可以在CPython源码的Include/graminit.h和Include/token.h文件中找到。

下面是对上面列表翻译后的一个树状结构,可以看到原来的代码都被翻译成一颗工整的语法树结构了。

在CPython中,Python的代码最终会被转化成字节码,再由虚拟机对它们进行解析,Python的虚拟机是一种基于栈形式的虚拟机。

在Python中有一个dis模块可以帮助把字节码转成可读的形式展示,下面这个例子对loop函数进行分析,这个函数循环对一个初始值为1的变量进行累加,直至变量的值等于5。

def loop():

x = 1

while x < 5:

x += 1

print(x)

import dis

dis.dis(loop)下面输出的字节码的指令含义都可以在library/dis中找到。

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (1)

2 STORE_FAST 0 (x)

3 4 SETUP_LOOP 28 (to 34)

>> 6 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

8 LOAD_CONST 2 (5)

10 COMPARE_OP 0 (<)

12 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 32

4 14 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

16 LOAD_CONST 1 (1)

18 INPLACE_ADD

20 STORE_FAST 0 (x)

5 22 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

24 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

26 CALL_FUNCTION 1

28 POP_TOP

30 JUMP_ABSOLUTE 6

>> 32 POP_BLOCK

>> 34 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

36 RETURN_VALUE

有了上面的基础,再来看下面这个例子:

from timeit import timeit

timeit('[]')

# 0.027015632018446922

timeit('list()')

# 0.44922116107773036

timeit('{}')

# 0.041279405006207526

timeit('dict()')

# 0.44984785199631006为什么用[]定义一个列表比用list()定义一个列表要更快呢?用dis模块进行分析后便很容易得出结论了,相比于[],执行list()时需要去加载list这个名字并查找和调用对应的函数,而执行[]时的指令数量比前者更少,因此它的执行速度也更快。

dis.dis('list()')

1 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (list)

2 CALL_FUNCTION 0

4 RETURN_VALUE

dis.dis('[]')

1 0 BUILD_LIST 0

2 RETURN_VALUE访问函数的__code__属性便能获得函数的code对象,code对象包含了这个函数解析后的字节码,使用opcode模块可获取字节码对应的指令。

import opcode

def add(a, b):

return a + b

add.__code__.co_code

# b'|\x00|\x01\x17\x00S\x00'

list(add.__code__.co_code)

# [124, 0, 124, 1, 23, 0, 83, 0]

for code in list(add.__code__.co_code):

print(opcode.opname[code])

# LOAD_FAST

# <0>

# LOAD_FAST

# POP_TOP

# BINARY_ADD

# <0>

# RETURN_VALUE

# <0>LEGB规则定义了Python对命名空间的查找顺序。

具体如下:

- Locals 函数内的命名空间

- Enclosing 外层函数的命名空间

- Globals 所在模块命名空间

- Builtins Python内置模块的名字空间

def outside():

v = 2

def inside():

print( # B

v) # E

inside() # L

outside() # Gglobals()

返回当前作用域的全局变量空间

locals()

返回当前作用域的本地变量空间

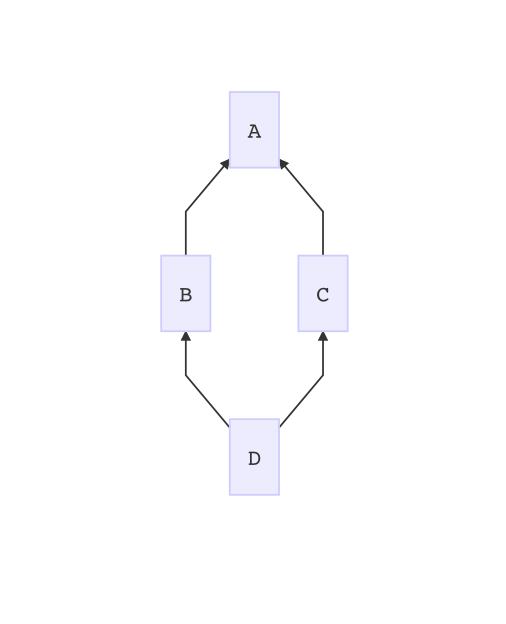

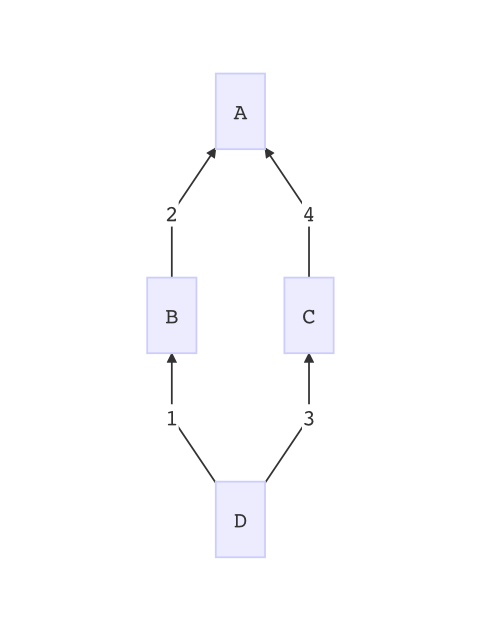

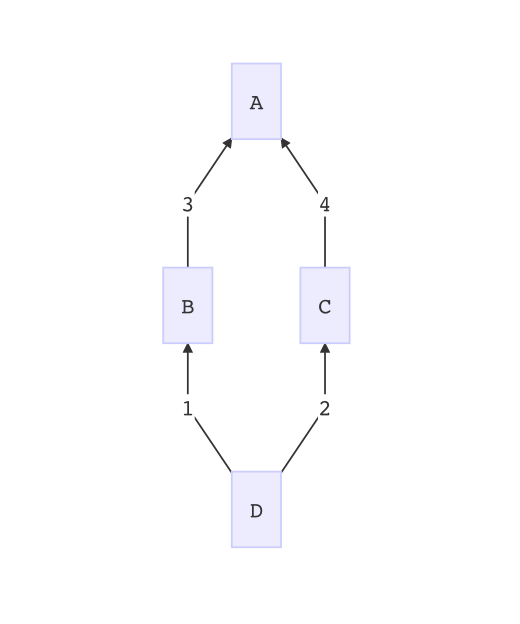

MRO决定了Python多继承中的方法解析顺序。

假如下面的一个类结构,D继承了B和C,B和C分别继承了A。

代码如下,其中A类和C类拥有方法f,分别打印A和C:

class A:

def f(self):

print('A')

class B(A): pass

class C(A):

def f(self):

print('C')

class D(B, C): pass

D().f()以上的输出在Python 2.7和3.6会有不同的输出,

其中2.7输出的是:

A

而3.6输出的是:

C

导致结果的差异是因为在旧式类(old-style class)和新式类(new-style class)中,MRO的规则有所不同。

执行以下语句:

D.__mro__可以看到在旧式类中,方法的查找顺序为D->B->A->C:

而在新式类中,方法的查找顺序为D->B->C->A:

在Python 3.x出现后,就只保留新式类了,采用的MRO规则为C3算法。

dir:返回指定对象的属性列表。

a = []

dir(a)

'''

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__delitem__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__iadd__', '__imul__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__reversed__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__setitem__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'append', 'clear', 'copy', 'count', 'extend', 'index', 'insert', 'pop', 'remove', 'reverse', 'sort']

'''getattr:获取一个对象中的属性,若不存在则抛出AttributeError异常,如果指定了默认值则返回默认值。

class A:

pass

getattr(A, 'a')

# AttributeError: type object 'A' has no attribute 'a'

getattr(A, 'a', 1)

# 1hasattr:检查一个对象是否有指定的属性。

hasattr(A, 'a')

# Falsesetattr:给一个对象的设置属性名和属性名的对应值。

if not hasattr(A, 'a'):

setattr(A, 'a', 2)

if hasattr(A, 'a'):

getattr(A, 'a')

# 2inspect:一个非常有用的内置模块,能够非常方便的获取对象信息。

import inspect

inspect.getmembers(a)Python的垃圾回收方式主要包括引用计数法和分代回收法。

引用计数

Python的垃圾回收主要依赖基于引用计数的回收算法,当一个对象的引用数为0时,Python虚拟机就会考虑回收对象占用的内存。

但引用计数的缺点也十分明显,那就是循环引用的问题,试想有两个容器对象,分别引用了对方作为自己的一个属性,这样在删除其中一个变量后,由于其对象还保留着引用,因此它的内存无法被释放。为了解决这个问题,Python使用了mark-sweep算法,定期扫描跟踪对象的引用情况,释放无用对象的内存。

分代回收

分代回收算法基于弱代假说的**,即:相对于存活时间长的对象,GC更加频繁去处理那些年轻的对象。

Python的分代回收机制把对象按照存活时间分成三个集合,每一个集合即为一个“代”,分别对于一个链表,当垃圾回收器进行收集时,会首先考虑去检查存活时间较短的对象集合。

PEP8定义了Python代码的风格指南。

- b (single lowercase letter)

- B (single uppercase letter)

- lowercase

- lower_case_with_underscores

- UPPERCASE

- UPPER_CASE_WITH_UNDERSCORES

- CapitalizedWords (or CapWords, or CamelCase -- so named because of the bumpy look of its letters [4]). This is also sometimes known as StudlyCaps.

- 实例方法的第一个参数名用

self。 - 类方法的第一个参数名为

cls。

一行的最大行宽不能超过79个字符数量,否则需要用反斜杠""结尾将其分成多行。

导入模块时应该注意分行导入:

Yes: import os

import sys

from subprocess import Popen, PIPE

No: import sys, os捕获异常时要尽量指定其异常类型,否则易导致异常被掩盖等问题。

# Yes

try:

import platform_specific_module

except ImportError:

platform_specific_module = None布尔值比较

不要用==用于布尔值的比较。

Yes: if greeting:

No: if greeting == True:

Worse: if greeting is True:None比较

# Yes

if foo is not None

## No

if foo !== None

# No

if not foo is None类型比较

# Yes

if isinstance(obj, int):

# No

if type(obj) is type(1):PEP 8 - Style Guide for Python Code

__name__和__main__

当Python源文件被解释器执行时,解释器会把__main__赋值给起始模块的__name__,表示这是程序的主入口模块,而当Python源文件被当作模块被其他模块导入时,__name__的赋值则是模块的名称。

例如现在定义了一个源文件a.py如下:

print(__name__)

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('Hello')直接执行:

python3 a.py

# __main__

# Hello可以看到这时候a.py中的__name__的值是__main__,而现在编写另一个文件b.py,并且把a作为模块导入:

import a

# a这时候看到a.py中的__name__的值已经变成了a,因此也不会输出Hello。

使用if __name__ == '__main__'这种方式可以把模块即能当作模块来使用,也能当作脚本来直接执行,在Python中有几个模块就是采用了这种方式:

python3 -m http.server

python3 -m pip install requests

cat test.json | python3 -m json.tool__init__.py和__all__

在文件夹中定义一个名为__init__.py的文件意思是告诉解释器把目录当成一个Python模块。

例如现在定义了下面的一个目录:

├── __init__.py

├── l1.py

└── sub_package

├── __init__.py

└── l2.py

l1.py

from sub_package.l2 import l2_f

l2_f()

from sub_package import l2_f

l2_f()sub_package/_init_.py

from .l2 import l2_f

__all__ = ['l2_f']sub_package/l2.py

def l2_f():

print('l2')执行a.py:

python3 l1.py

# l2

# l2这两种方式都能导入l2.py中的函数,而在后面的导入方式中,当l1.py试图从sub_package导入一个函数时,它会检查sub_package目录下的__init__.py,而__init__.py把l2.py的函数导入进了自身的命名空间里面,于是l2_f函数可以顺利被l1.py导入。

__all__指定了模块暴露的接口列表。

Python包括多种容器数据类型:

| 数据类型 | 可变 | 有序 |

|---|---|---|

| list | yes | yes |

| tuple | no | yes |

| str | no | yes |

| range | no | yes |

| bytes | no | yes |

| bytearray | yes | yes |

| array | yes | yes |

| set | yes | no |

| frozenset | no | no |

| dict | yes | no |

| OrderedDict | yes | yes |

首先看鸭子类型(duck typing)的定义:

当看到一只鸟走起来像鸭子、游泳起来像鸭子、叫起来也像鸭子,那么这只鸟就可以被称为鸭子。

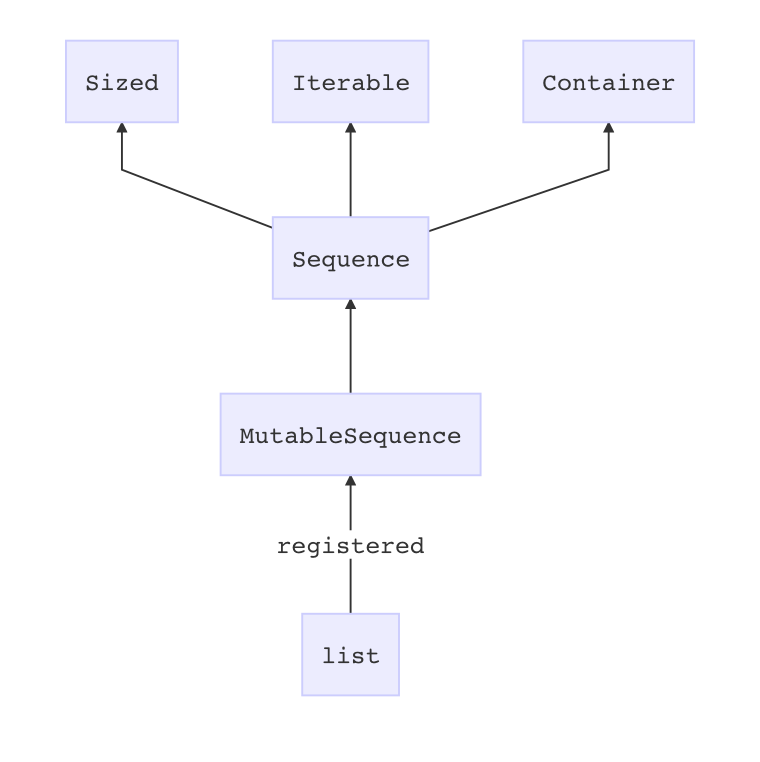

Python的容器抽象类也有鸭子类型的体现,看下面这个例子:

from collections.abc import Sized

class A:

def __len__(self):

return 0

len(A())

# 0

issubclass(A, Sized) # use __instancecheck__

# True

isinstance(A(), Sized) # use __subclasscheck__

# True定义了一个类A,并定义了它的__len__方法,这个方法会在调用len函数时被调用到。

Sized是一个collections.abc模块定义的一个容器抽象类,但是A类没有继承Sized类,为什么Python却认为A是Sized的一个子类呢?

如果仔细看Sized类的定义,它实现了一个__subclasshook__的方法,这个方法会在执行issubclass函数时会被调用,Sized类会检查A是否拥有一个名为__len__的方法,如果拥有则返回True,于是issubclass的调用会返回True。

这也就体现了,如果A拥有__len__的方法,那么它就是一个Sized。

class Sized(metaclass=ABCMeta):

__slots__ = ()

@abstractmethod

def __len__(self):

return 0

@classmethod

def __subclasshook__(cls, C):

if cls is Sized:

if any("__len__" in B.__dict__ for B in C.__mro__):

return True

return NotImplemented下图是list与其它容器类之间的关系:

了解更多抽象容器类可查看collections.abc这个模块。

l = []

l.append(1)

# [1]

l.extend([2, 3])

# [1, 2, 3]

l.pop()

# [1, 2]

l.insert(1, 3)

# [1, 3, 2]

l.index(1)

# 0

l.sort()

# [1, 2, 3]

l.reverse()

# [3, 2, 1]

l.count(2)

# 1

l.remove(1)

# [3, 2]

l.clear()

# []t = (1, 2)

t[0]

# 1

t[1]

# 2d = {}

d['a'] = 1

# {'a': 1}

d.get('a')

# 1

d.get('b')

# None

d.get('b', 2)

# 2

d.values()

# dict_values([1])

d.keys()

# dict_keys(['a'])

d.items()

# dict_items([('a', 1)])

d.pop('a')

# 1

d

# {}s1 = set([1, 2, 3])

s2 = set([3, 4, 5])

s1 - s2

# {1, 2}

s1 & s2

# {3}

s1 | s2

# {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

s1 ^ s2

# {1, 2, 4, 5}s = 'string'

b = b'string'

b == s

# False

b == s.encode()

# True

memoryview(b).to_list()

# [115, 116, 114, 105, 110, 103]

'-'.join(map(chr, memoryview(s.encode()).tolist()))

# 's-t-r-i-n-g'from collections import deque

queue = deque(["a", "b", "c"])

queue.append("d")

queue.append("e")

queue.popleft()

# 'a'

queue.popleft()

# 'b'

queue

# deque(['c', 'd', 'e'])from queue import Queue

q = Queue()

q.put(1)

q.get()

# 1

q.empty()

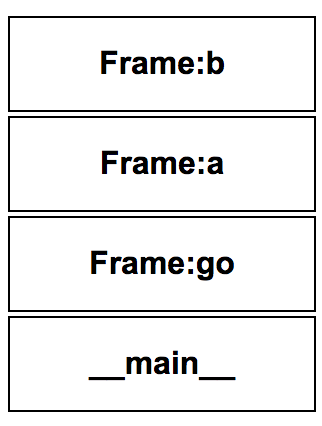

# TruePython通过栈帧来关联函数之间的调用,每次调用函数时,函数的栈帧会放在调用栈上,调用栈的深度随着函数的调用深度增长,栈帧对象包含了函数的code对象,函数的局部变量数据,前一个栈帧和行号等信息。

def c():

pass

def b():

pass

def a():

b()

c()

def go():

a()

go()在下面这个例子中,f函数通过获取调用链中前一个栈帧的信息,拿到add函数栈帧中局部变量a与b的值,使得f函数在不接收参数的情况下完成了透明的加法:

import inspect

def f():

current_frame = inspect.currentframe()

back_frame = current_frame.f_back

a = back_frame.f_locals['a']

b = back_frame.f_locals['b']

return a + b

def add(a, b):

print(f())

add(1, 2)

# 3下面这个函数展示了参数的定义形式:

- a是一个普通参数,调用时必须要指定一个值,否则会报错。

- b是一个指定了默认值(None)的参数,如果调用时没有指定值,那么b的值便是None。

- args和kwargs分别是一个tuple和dict,它们封装了剩下的可变长参数,其中关键字参数会传递到kwargs上,而非关键字参数会传递到args上。

def f(a, b=None, *args, **kwargs):

print(a)

print(b)

print(args)

print(kwargs)

f(1, 2, 3, 4, keyword=5)

# 1

# 2

# (3, 4)

# {'keyword': 5}要想查看函数的参数签名信息,可使用inspect模块的signature函数,它会返回一个签名类的对象,上面包含了函数的参数名字以及注解等信息。

import inspect

def func(f, a: int, b: int):

return f(a, b)

sig = inspect.signature(func)

type(sig)

# <class 'inspect.Signature'>

sig.parameters

# OrderedDict([('f', <Parameter "f">), ('a', <Parameter "a:int">), ('b', <Parameter "b:int">)])

sig.parameters.get('a').annotation

# <class 'int'>使用functools模块的partial可以将已知值绑定到函数的一个或多个参数上:

import operator

from functools import partial

def func(f, a: int, b: int):

return f(a, b)

add = partial(func, operator.add)

sub = partial(func, operator.sub)

add(1, 2)

# 3

sub(1, 2)

# -1装饰器是一个函数,它用于给已有函数扩展功能,它通常接收一个函数作为参数,并返回一个新的函数。

装饰器可配合@符号十分简洁地应用在函数上。

def tag(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

func_result = func(*args, **kwargs)

return '<{tag}>{content}</{tag}>'.format(tag=func.__name__, content=func_result)

return wrapper

@tag

def h1(text):

return text

@tag

def p(text):

return text

def div(text):

return text

html = h1(p('Hello World'))

print(html)

# <h1><p>Hello World</p></h1>

html2 = tag(div)('Hello World')

print(html2)

# <div>Hello World</div>类装饰器

class Tag:

def __init__(self, func):

self.func = func

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

func_result = self.func(*args, **kwargs)

return '<{tag}>{content}</{tag}>'.format(tag=self.func.__name__, content=func_result)

@Tag

def h1(text):

return text

html = h1('Hello World')

print(html)yield能把一个函数变成一个generator,与return不同,yield在函数中返回值时会保存函数的状态,使下一次调用函数时会从上一次的状态继续执行,即从yield的下一条语句开始执行。

def fib(max):

n, a, b = 0, 0, 1

while n < max:

yield(b)

a, b = b, a + b

n = n + 1

f = fib(10)

next(f)

# 1

next(f)

# 1

next(f)

# 2

f.send(None)

# 3

for num in f:

print(num)

# 5

# 8

# 13

# 21

# 34

# 55

next(f)

# StopIteration当一个类的方法名前以单下划线或双下滑线开头时,通常表示这个方法是一个私有方法。

但这只是一种约定俗成的方式,对于外部来说,以单下划线开头的方法依然是可见的,而双下划线的方法则被改写成_类名__方法名存放在名字空间中,所以如果B继承了A,它是访问不到以双下划线开头的方法的。

class A:

def public_method(self):

pass

def _private_method(self):

pass

def __private_method(self):

pass

a = A()

a.public_method()

# None

a._private_method()

# None

a.__private_method()

# AttributeError: 'A' object has no attribute '__A_private_method'

a._A__private_method()

# None

A.__dict__

# mappingproxy({'_A__private_method': <function __main__.A.__private_method>,

# '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'A' objects>,

# '__doc__': None,

# '__module__': '__main__',

# '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'A' objects>,

# '_private_method': <function __main__.A._private_method>,

# 'public_method': <function __main__.A.public_method>})类方法本质上是一个函数,通过绑定对象的方式依附在类上成为方法。

假如有下面一个类:

class A:

def __init__(self):

self.val = 1

def f(self):

return self.val可以看到f是A的属性列表中的一个函数:

A.f

# <function __main__.A.f>

A.__dict__['f']

# <function __main__.A.f>而当直接用A.f()的方式调用f方法时,会抛出一个异常,异常的原因很直接,参数列表有一个self参数,调用时却没有指定这个参数。而用A().f()的方式调用f方法时同样没有指定参数,却能正常执行,这是为什么呢?

执行A().f语句可以发现,这时候的f不再是一个函数,而是一个绑定方法,而它绑定的对象则是一个A的实例对象,换句话说,这时候f参数中的self已经跟这个实例对象绑定在一起了,所以用实例调用一个普通方法时,无须人为地去指定第一个参数。

A.f()

# TypeError: f() missing 1 required positional argument: 'self'

A().f() # auto binding

# 1

A().f

# <bound method A.f of <__main__.A object at 0x121a3bac8>>通过调用f函数的__get__(函数的描述器行为)方法来为函数绑定到一个对象上:

class B:

def __init__(self):

self.val = 'B'

A.f.__get__(B(), B)

# <bound method A.f of <__main__.B object at 0x111f9b198>>

A.f.__get__(B(), B)()

# B通过types模块的MethodType动态把方法附加到一个实例上:

import types

def g(self):

return self.val + 1

a.g = types.MethodType(g, a)

a.g()

# 2类方法分为普通方法,静态方法和类方法,静态方法和类方法可分别通过classmethod和staticmethod装饰器来定义。

区别于普通方法,类方法的第一个参数绑定的是类对象,因此可以不需要实例对象,直接用类调用类方法执行。

而静态方法则没有绑定参数,跟类方法一样,可以通过类或者实例直接调用。

class C:

def instance_method(self):

print(self)

@classmethod

def class_method(cls):

print(cls)

@staticmethod

def static_method():

pass

C.instance_method

# <function __main__.C.instance_method>

C.instance_method()

# TypeError: instance_method() missing 1 required positional argument: 'self'

C().instance_method()

# <__main__.C object at 0x121133b00>

C.class_method

# <bound method C.class_method of <class '__main__.C'>>

C.class_method()

# <class '__main__.C'>

C().class_method()

# <class '__main__.C'>

C.static_method

# <function __main__.C.static_method>

C.static_method()

# None

C().static_method()

# None通过输出可以看到的一点就是,类方法是一个已经绑定类对象的方法,而普通方法和静态方法在被调用前只是一个普通函数。

property是一个内置函数,它可以将方法与属性调用绑定在一起。

看下面这个例子,Person类有个年龄属性age,现在想要在对这个属性赋值时给它加一个类型校验,借助于property函数便能在不需要修改用法的情况下为属性加上getter/setter方法:

class Person:

def __init__(self, age):

self._age = age

@property

def age(self):

return self._age

@age.setter

def age(self, age):

if not isinstance(age, int):

raise TypeError('age must be an integer')

self._age = age

p = Person(20)

print(p.age)

# 20

p.age = 30

print(p.age)

# 30

p.age = '40'

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "test.py", line 20, in <module>

# p.age = '40'

# File "test.py", line 12, in age

# raise TypeError('age must be an integer')

# TypeError: age must be an integerproperty还常用于延迟计算以及属性缓存,例如下面Circle类的area属性,只有在被访问到的情况下才进行计算,并把结果缓存到实例的属性上。

class Circle(object):

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

@property

def area(self):

if not hasattr(self, '_cache_area'):

print('evalute')

setattr(self, '_cache_area', 3.14 * self.radius ** 2)

return getattr(self, '_cache_area')

c = Circle(4)

print(c.area)

# evalute

# 50.24

print(c.area)

# 50.24上面谈论到的property也好,classmethod和staticmethod也好,甚至是所有的函数,本质上都是实现了描述器协议的对象。

描述器是一个绑定行为的对象属性,如果一个对象定义了__set__()和__get__(),那么它就是一个数据描述器,如果只定义了__get__(),那么它就是一个非数据描述器。

下面定义了一个描述器类Integer,这个类的一个实例作为类属性赋给类C的num变量上,当C的实例访问这个属性时便会触发描述器协议,调用描述器的__get__方法,其中第一个参数是实例本身,而第二个参数是实例所归属的类(是否跟实例方法的调用有异曲同工之妙?),如果属性是以类的形式访问,那么第一个参数的值为None;相似地,当对这个属性进行赋值操作时,则会调用描述器的__set__方法,借用这个特性可以方便对属性做一些校验操作。

class Integer:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.val = None

def __get__(self, obj, obj_type):

print(obj, obj_type)

return self.name

def __set__(self, obj, val):

if not isinstance(val, int):

raise Exception('value must be an integer!')

print('set value to {}'.format(val))

self.val = val

class C:

num = Integer('i')

c = C()

c.num

# <__main__.C object at 0x10cc735c0> <class '__main__.C'>

c.num = 5

# set value to 5

c.num = '5'

# Exception: value must be an integer!说到这里已经可以猜到property是如何实现的了,实际上Python官方已经给出了一份模拟property实现的Python代码:

class Property(object):

"Emulate PyProperty_Type() in Objects/descrobject.c"

def __init__(self, fget=None, fset=None, fdel=None, doc=None):

self.fget = fget

self.fset = fset

self.fdel = fdel

if doc is None and fget is not None:

doc = fget.__doc__

self.__doc__ = doc

def __get__(self, obj, objtype=None):

if obj is None:

return self

if self.fget is None:

raise AttributeError("unreadable attribute")

return self.fget(obj)

def __set__(self, obj, value):

if self.fset is None:

raise AttributeError("can't set attribute")

self.fset(obj, value)

def __delete__(self, obj):

if self.fdel is None:

raise AttributeError("can't delete attribute")

self.fdel(obj)

def getter(self, fget):

return type(self)(fget, self.fset, self.fdel, self.__doc__)

def setter(self, fset):

return type(self)(self.fget, fset, self.fdel, self.__doc__)

def deleter(self, fdel):

return type(self)(self.fget, self.fset, fdel, self.__doc__)classmethod的实现则更为简单一些:

class ClassMethod(object):

"Emulate PyClassMethod_Type() in Objects/funcobject.c"

def __init__(self, f):

self.f = f

def __get__(self, obj, klass=None):

if klass is None:

klass = type(obj)

def newfunc(*args):

return self.f(klass, *args)

return newfuncPython的每个运算符在背后都对于着特定的方法,重写这些方法可以实现自定义操作符应用在对象时的行为。

二元运算符

| 操作 | 方法 |

|---|---|

| + | object._add_(self, other) |

| - | object._sub_(self, other) |

| * | object._mul_(self, other) |

| // | object._floordiv_(self, other) |

| / | object._truediv_(self, other) |

| % | object._mod_(self, other) |

| ** | object._pow_(self, other[, modulo]) |

| << | object._lshift_(self, other) |

| >> | object._rshift_(self, other) |

| & | object._and_(self, other) |

| ^ | object._xor_(self, other) |

| | | object._or_(self, other) |

扩展赋值运算符

| 操作 | 方法 |

|---|---|

| += | object._iadd_(self, other) |

| -= | object._isub_(self, other) |

| *= | object._imul_(self, other) |

| /= | object._idiv_(self, other) |

| //= | object._ifloordiv_(self, other) |

| %= | object._imod_(self, other) |

| **= | object._ipow_(self, other[, modulo]) |

| <<= | object._ilshift_(self, other) |

| >>= | object._irshift_(self, other) |

| &= | object._iand_(self, other) |

| ^= | object._ixor_(self, other) |

| |= | object._ior_(self, other) |

一元运算符

| 操作 | 方法 |

|---|---|

| - | object._neg_(self) |

| + | object._pos_(self) |

| abs() | object._abs_(self) |

| ~ | object._invert_(self) |

| complex() | object._complex_(self) |

| int() | object._int_(self) |

| long() | object._long_(self) |

| float() | object._float_(self) |

| oct() | object._oct_(self) |

| hex() | object._hex_(self) |

比较运算符

| 操作 | 方法 |

|---|---|

| < | object._lt_(self, other) |

| <= | object._le_(self, other) |

| == | object._eq_(self, other) |

| != | object._ne_(self, other) |

| >= | object._ge_(self, other) |

| > | object._gt_(self, other) |

覆盖操作符的行为:

class Num:

def __init__(self, val=0):

self.val = val

def __add__(self, other):

return Num(self.val - other)

def __sub__(self, other):

return Num(self.val + other)

def __repr__(self):

return str(self.val)

num = Num(1)

result = num + 1

# 0

result = num - 1

# 2对于定义了__slots__的类,无法随意添加属性到类上,而是只能对__slots__指定的属性进行操作。

而这也是一种对于存在大量简单对象时,有效降低内存占用的其中一种方式:

class MemoryCheck:

def __enter__(self):

tracemalloc.start()

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb):

snapshot = tracemalloc.take_snapshot()

top_stats = snapshot.statistics('lineno')

print("[ Top 1 ]")

for stat in top_stats[:1]:

print(stat)

with MemoryCheck():

class Object:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

objs = []

for i in range(1000000):

objs.append(Object(i, i + 1))

'''

[ Top 1 ]

<ipython-input-132-47931446414b>:4: size=107 MiB, count=1999958, average=56 B

'''with MemoryCheck():

class Object:

__slots__ = ('x', 'y')

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

objs = []

for i in range(1000000):

objs.append(Object(i, i + 1))

'''

[ Top 1 ]

<ipython-input-133-cc08066bfb2a>:9: size=88.4 MiB, count=1999747, average=46 B

'''元类能动态地创建类,而且也能控制类的创建行为。

import inspect

class MethodLowerCase(type):

def __new__(mcs, name, bases, attrs):

for name, val in attrs.items():

if callable(val):

if name.lower() != name:

print('method: {} should be lowercase'.format(name))

else:

print('method: {} is valid'.format(name))

new_cls = type.__new__(mcs, name, bases, attrs)

return new_cls

class Test(metaclass=MethodLowerCase):

def test_a(self):

pass

def testB(self):

pass

# method: test_a is valid

# method: testB should be lowercaseimport this遍历列表

array = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for i in range(len(array)):

print (i, array[i])

# Pythonic

for i, item in enumerate(array):

print (i, item)对列表的操作

array = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

new_array = []

for item in array:

new_array.append(str(item))

# Pythonic

new_array = [str(item) for item in array]

# Generator

new_array = (str(item) for item in array)

# 函数式

new_array = map(str, array)列表推导

# 生成列表

[ i*i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0 ]

# 生成集合

{ i*i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0 }

# 生成字典

{ i:i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0 }上下文管理器

file = open('file', 'w')

file.write(123)

file.close()

# Pythonic

with open('file', 'w') as file:

file.write(123)条件判断

if x is True:

y = 1

else:

y = -1

# Pythonic

y = 1 if x is True else -1构造矩阵

y = [0 for _ in range(100000000)]

# Pythonic

y = [0] * 100000000装饰器

def logic(x):

if x < 0:

return False

print (x)

return True

#Pythonic

def check_gt_zero(func):

def wrapper(x):

if x < 0:

return False

return func(x)

return wrapper

@check_gt_zero

def logic(x):

print (x)

return True变量交换

temp = y

y = x

x = temp

# Pythonic

x, y = y, x切片

array = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

l = len(array)

for i in range(l/2):

temp = array[l - i - 1]

array[l - i - 1] = array[i]

array[i] = temp

array = list(reversed(array))

# Pythonic

array = array[::-1]读取文件

CHUNK_SIZE = 1024

with open('test.json') as f:

chunk = f.read(CHUNK_SIZE)

while chunk:

if chunk:

print(chunk)

chunk = f.read(CHUNK_SIZE)

from functools import partial

# Pythonic

with open('test.json') as f:

for piece in iter(partial(f.read, CHUNK_SIZE), ''):

print (piece)

# Lambda

with open('test.json') as f:

for piece in iter(lambda: f.read(CHUNK_SIZE), ''):

print (piece)for-else和try-else语法

is_for_finished = True

try:

for item in array:

print (item)

# raise Exception

except:

is_for_finished = False

if is_for_finished is True:

print ('complete')

# Pythonic

for item in array:

print (item)

# raise Exception

else:

print ('complete')

try:

print ('try')

# raise Exception

except Exception:

print ('exception')

else:

print ('complete')函数参数解压

def draw_point(x, y):

# do some magic

point_foo = (3, 4)

point_bar = {'y': 3, 'x': 2}

draw_point(*point_foo)

draw_point(**point_bar)列表/元组解压

first, second, *rest = (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)"Print To"语法

print ("hello world", file=open("myfile", "w"))字典缺省值

d = {}

try:

d['count'] = d['count'] + 1

except KeyError:

d['count'] = 0

# Pythonic

d['count'] = d.get('count', 0) + 1链式比较符

if x < 100 and x > 0:

print(x)

# Pythonic

if 0 < x < 100:

print(x)多行字符串

s = ("longlongstringiii"

"iiiiiiiii"

"iiiiiii")in表达式

if 'string'.find('ring') > 0:

print ('find')

# Pythonic

if 'ring' in 'string':

print ('find')

for r in ['ring', 'ring1', 'ring2']:

if r == 'ring':

print ('find')

# Pythonic

if 'ring' in ['ring', 'ring1', 'ring2']:

print('find')字符串连接

array = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

s = array[0]

for char in array[1:]:

s += ',' + char

# Pythonic

s = ','.join(array)列表合并字典

keys = ['a', 'b', 'c']

values = [1, 2, 3]

d = {}

for key, value in zip(keys, values):

d[key] = value

# Better

d = dict(zip(keys, values))

# Pythonic

d = {key: value for key, value in zip(keys, values)}all和any

flag = True

for cond in conditions:

if cond is False:

flag = False

break

# Pythonic

flag = all(conditions)

flag = False

for cond in conditions:

if cond is True:

flag = True

break

# Pythonic

flag = any(conditions)or

not_null_string = '' or 'string1' or 'string2'

# string1方法提取

for item in ['b', 'c']:

array.append(item)

# Faster

append = array.append

for item in ['b', 'c']:

append(item)单例模式

from [module] import [single_instance]用<>代替!=

In [1]: from __future__ import barry_as_FLUFL

In [2]: 1 == 1

Out[2]: True

In [3]: 1 != 1

File "<ipython-input-3-1ec724d2c3b1>", line 1

1 != 1

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In [4]: 1 <> 1

Out[4]: False格式化一个json文件

python -m json.tool test.json

echo '{"json":"obj"}' | python -m json.tool # 管道

开启本地目录的HTTP服务器

python3 -m http.server 8080def append_to(element, to=[]):

to.append(element)

return to

my_list = append_to(12)

print(my_list)

my_other_list = append_to(42)

print(my_other_list)

# [12]

# [12, 42]def create_multipliers():

return [lambda x : i * x for i in range(5)]

for multiplier in create_multipliers():

print multiplier(2)

# 8

# 8

# 8

# 8

# 8在下面这个例子中, 两个值相等的整形变量在两次比较地址时出现了不一样的情况,原因时因为Python会把频繁使用的小整数放在内存池中,因此在Python中使用范围在[-5,256]的数字时都会得到相同的内存地址。

a = 256

b = 256

id(a) == id(b)

# True

a = 257

b = 257

id(a) == id(b)

# False受制于GIL(Global Interpreter Lock,全局解释锁)的存在,Python进程中的多线程无法利用多核的计算资源,同一时间内只有一个线程可以持有全局解释锁,执行代码指令。

根据Python虚拟机中的执行机制,每当线程执行若干条虚拟指令后,时间片就会调度给另一个线程。这个间隔时间可以用sys模块的getswitchinterval函数看到:

sys.getswitchinterval()

# 0.005以上输出表明,每隔0.005秒,这种调度便会发生一次。

所以可以看到,由于这种机制的存在,下面这两段代码在相同环境下,很可能是带线程的版本执行时间更长:

def count(n):

while n > 0:

n -= 1

count(100000000)

count(100000000)

t1 = Thread(target=count,args=(100000000,))

t1.start()

t2 = Thread(target=count,args=(100000000,))

t2.start()

t1.join();

t2.join()在Python中多线程更适用于IO密集型的任务,比如网络任务,异步请求等,如果需要获得并行的能力,应该使用多进程模块。

在一个Python进程当中,可以有多个解释器的存在,一个解释器中保存了指向其他解释器的指针,以及一个指向线程状态表的指针,每当创建一个线程,就会往状态表中添加一条记录,线程状态(tstate)对应了真实的线程,还包含了其对应的栈帧信息。

在Python的实现里广泛使用了内存池技术来提高性能,一些相同且无特殊意义的对象也常被池化,减少了对象数量以及内存占用。

举其中一个例子,有A,B,C三个类,其中只有C定义了文档字符串,这时候用A.__doc__ is B.__doc__就能发现,它们使用的内存地址是一样的,说明类的__doc__属性默认都被池化了,而再执行A.__doc__ is C.__doc__就会看到结果是False,说明只有定义了doc-string的时候,__doc__属性才会被分配新的内存。

class A: pass

class B: pass

class C:

'''doc-string'''

pass

A is B

# False

A.__doc__ is B.__doc__

# True

A.__doc__ is C.__doc__

# False对于简单字符串,Python会将其放进内存池中,当字符串的引用变为0时,再把它的内存释放。

a = 'HelloWorld'

b = 'HelloWorld'

a is b

# True但再看下面这个例子,在字符串中间插入一个空格后,虽然a和b还是相同的值,但是内存地址却是不一样的:

a = 'Hello World'

b = 'Hello World'

a is b

# False

a = ' '

b = ' '

a is b

# True这是因为Python认为的简单字符串一般只包含字母或数字,因此对于这种带有额外字符的字符串,Python是不会将其池化的。

a = '汉字'

b = '汉字'

a is b

# False在Python 3.x中,可以用sys模块的intern方法来给程序运行期间动态生成的字符串池化。

import sys

a = '汉字'

b = '汉字'

a = sys.intern(a)

b = sys.intern(b)

a is b

# True利用sys模块的settrace函数可以注册线程的跟踪函数,跟踪函数应具有三个参数:frame,event 和arg。

- frame:当前的堆栈帧。

- event:一个代表跟踪事件字符串,其值为'call'、 'line'、 'return'、 'exception'、 'c_call'、 'c_return'或'c_exception'。

- arg:在event不同的时候有不一样的含义。

在下面这个例子中,给全局设置了一个跟踪函数,当程序发生调用事件(例如一个函数调用了另一个函数)时,Python便会回调跟踪函数,把函数的栈帧,事件类型以及时间类型的参数传入钩子函数中。

class TreeStdout:

"""把标准输出显示出函数调用层级的关系

"""

def __init__(self, fill_symbol="\t"):

self.stack = []

self.old_write = sys.stdout.write

self.symbol = fill_symbol

def _get_stdout_writer(self, depth):

def _writer(data):

if data != "\n":

self.old_write(self.symbol * depth + data)

else:

self.old_write(data)

return _writer

def _trace_calls(self, frame, event, arg):

if event == 'return':

self.stack.pop()

if event != 'call':

return

co = frame.f_code

func_name = co.co_name

if func_name == 'write':

return

caller = frame.f_back

if caller is None:

return

caller_name = caller.f_code.co_name

self.stack.append(caller_name)

depth = len(self.stack) - 1

sys.stdout.write = self._get_stdout_writer(depth)

return self._trace_calls

def __enter__(self):

sys.settrace(self._trace_calls)

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb):

self.stack.clear()

sys.stdout.write = self.old_write

sys.settrace(None)

def f():

print('inside f()')

def d():

print('inside d()')

def e():

print('inside e()')

f()

def c():

print('inside c()')

d()

e()

e()

def b():

print('inside b()')

def a():

print('inside a()')

b()

c()

with TreeStdout():

a()

# inside a()

# inside b()

# inside c()

# inside d()

# inside e()

# inside f()

# inside e()

# inside f()欢迎学习讨论和交流,如果觉得本文对你有帮助,欢迎点个star,谢谢。