This blog is about a programming assignment in HKU multimedia class. This is a group project and my teammate is Meng Liuchen. Thanks a lot for her work in the project!

The assignment is composed of two parts:a) Color Space Conversion and b) Lossless Image Compression.

The assignment requires to implement a color space conversion algorithm, which converts color between RGB and YUV space, and investigate compression efficiency difference between the two color space.

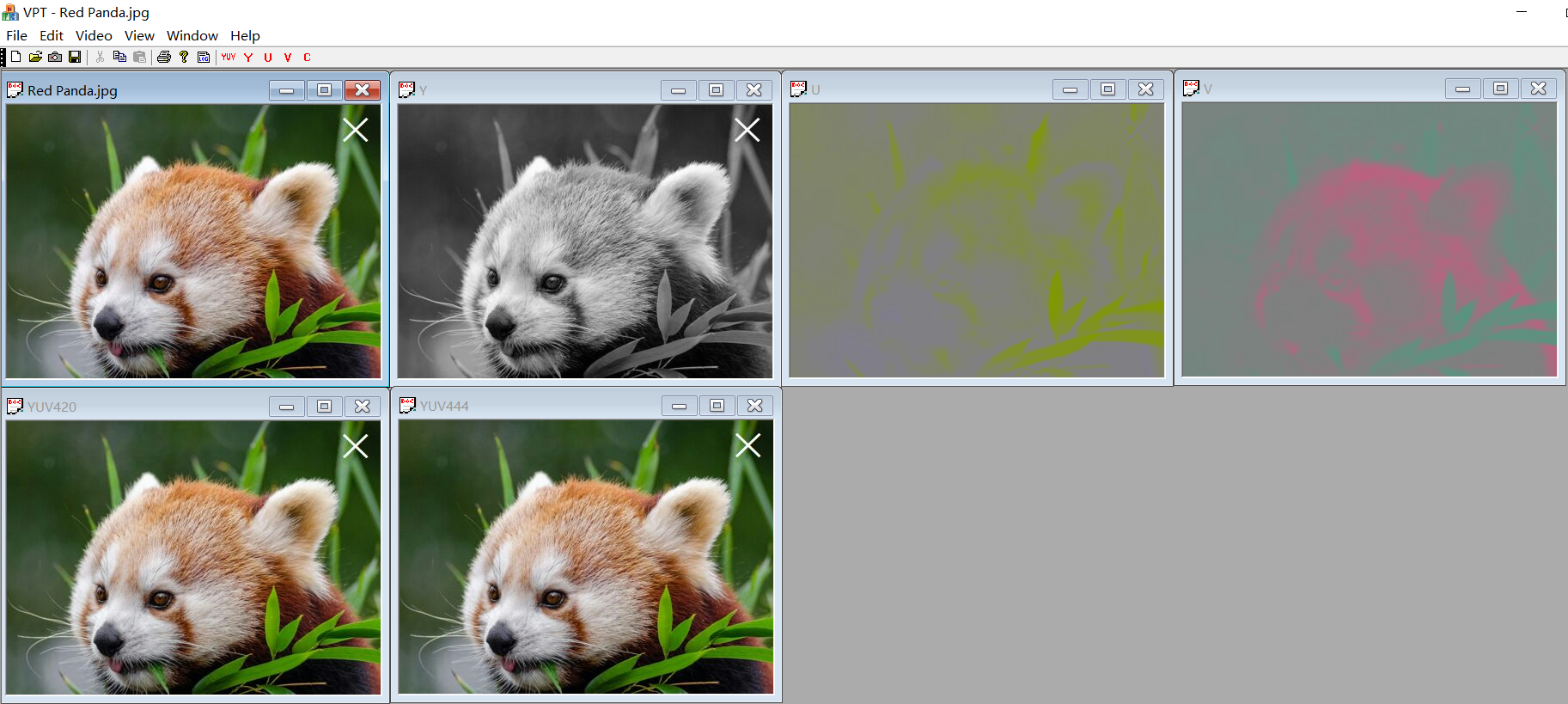

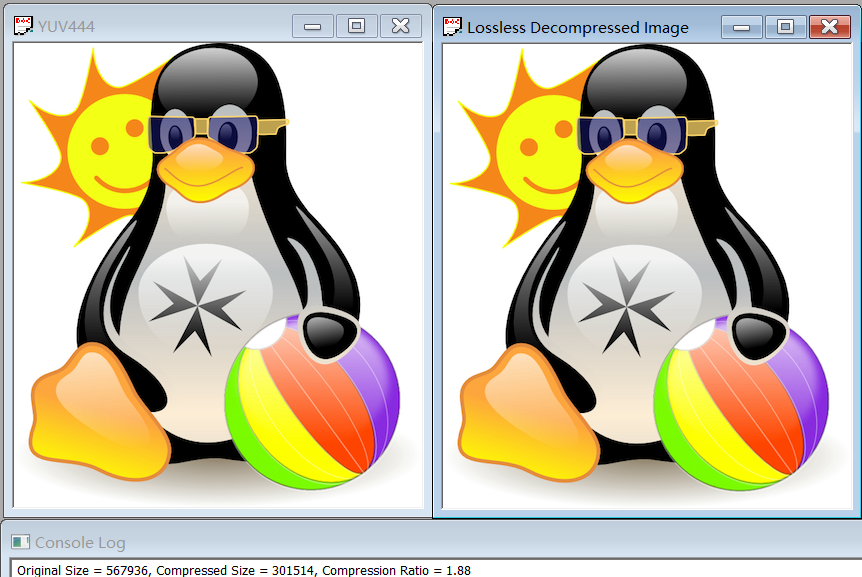

The user interface looks like the image below.

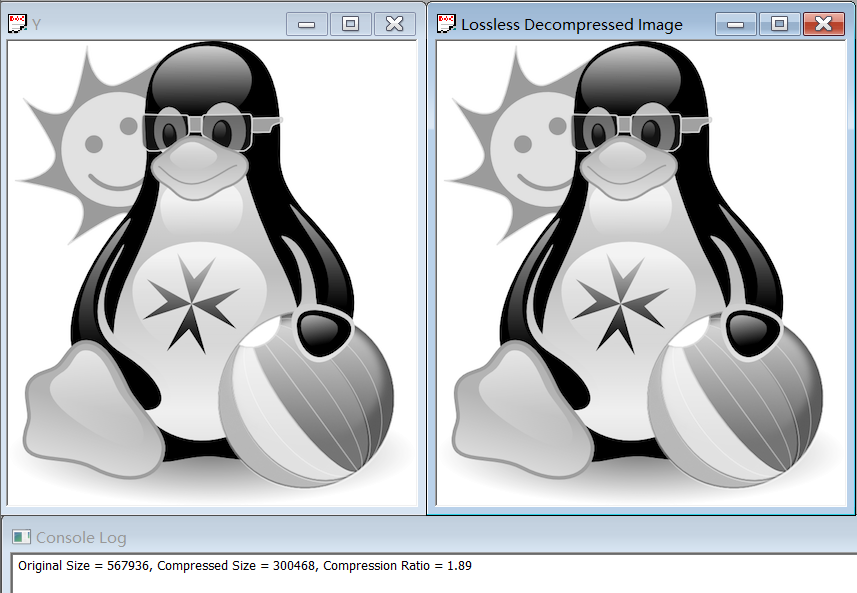

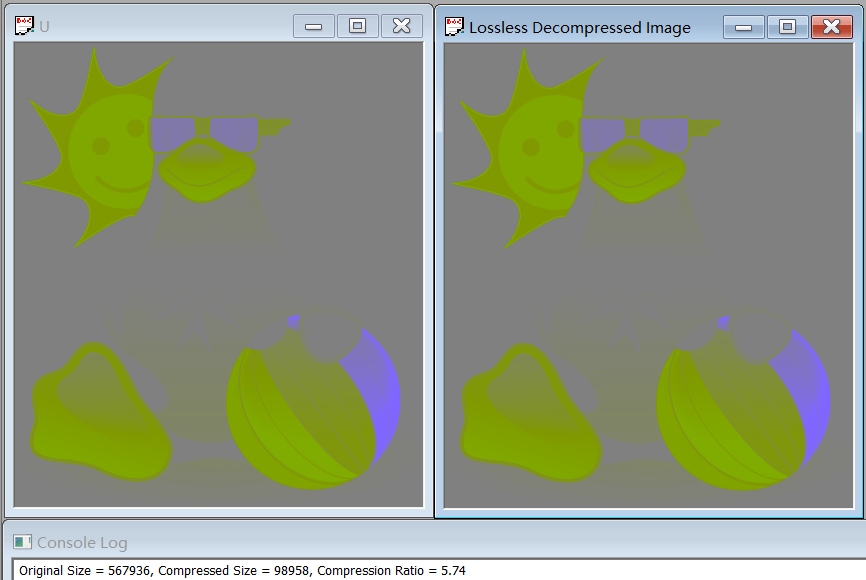

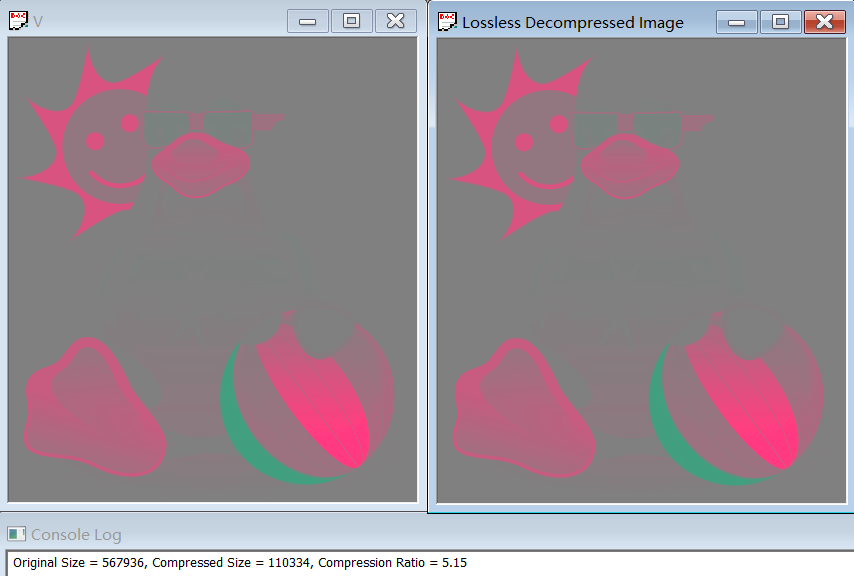

The Red Panda.jpg is the original image. By pressing the YUV button, YUV444 and YUV420 can be seen on the screen. In addition, the YUV color image can be divided into Y-, U- and V-component images by pressing the Y, U and V button.

The C button is used to accomplish the lossless image compression. In my blog Compression Algorith in Multimedia, I introduced several lossless algorithm in image compression and RLE is used in this assignment.

// This function converts input RGB image to a YUV image.

void CAppConvert::RGBtoYUV(unsigned char *pRGB, unsigned char *pYUV) {

int i, j ;

int r, g, b ;

int Y, U, V ;

for(j = 0; j < height; j++) {

for(i = 0; i < width; i++) {

b = pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3] ;

g = pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1] ;

r = pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2] ;

Y = 0.299 * r + 0.587 * g + 0.114 * b;

U = -0.169 * r - 0.331 * g + 0.500 * b + 128;

V = 0.500 * r - 0.419 * g - 0.081 * b + 128;

if (Y < 0) {Y = 0;}

else if (Y > 255) { Y = 255; }

if (U < 0) { U = 0; }

else if (U > 255) { U = 255; }

if (V < 0) { V = 0; }

else if (V > 255) { V = 255; }

pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3] = Y ;

pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1] = U ;

pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2] = V ;

}

}

}

// This function converts input YUV image to a RGB image.

void CAppConvert::YUVtoRGB(unsigned char *pYUV, unsigned char *pRGB) {

int i, j ;

int y, u, v;

int R, G, B;

for(j = 0; j < height; j++) {

for(i = 0; i < width; i++) {

y = pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3] ;

u = pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1];

v = pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2];

R = y + 1.4 * (v - 128);

G = y - 0.343 * (u - 128) - 0.711 * (v - 128);

B = y + 1.765 * (u - 128);

if (R < 0) { R = 0; }

else if (R > 255) { R = 255; }

if (G < 0) { G = 0; }

else if (G > 255) { G = 255; }

if (B < 0) { B = 0; }

else if (B > 255) { B = 255; }

pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3] = B ;

pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1] = G;

pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2] = R;

}

}

}

The R-, G-, B- component are stored in the order of BGR, so the size of the data is weightheight3, and the range of R, G, B is [0,255]. If the pixel is on the image in line j column i, the R, G, B component of this pixel are stored in pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3], pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1], pRGB[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2].

Since the YUV444 has the same storage mode of RGB, so the Y, U, V components of pixel in line j column i are stored in pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3], pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 1], pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3 + 2] as well.

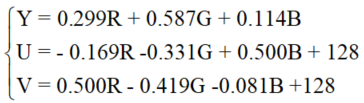

The conversion of RGB colors into full-range YUV colors is described by the following equation:

To convert a full-range YUV colors into RGB colors is described by the following equation:

Using the data that we extracted from the image and the conversion equation, we can obtain the conversion between RGB and YUV444 and the Y-, U-, V- component of the image.

void CAppConvert::YUVtoYUV420(unsigned char *pYUV, unsigned char *pYUV420) {

int i, j ;

int sum ;

int si0, si1, sj0, sj1 ;

for(j = 0; j < height; j++) {

for(i = 0; i < width; i++) {

pYUV420[(i + j * width) * 3] = pYUV[(i + j * width) * 3] ;

}

}

for(j = 0; j < height; j+=2) {

sj0 = j ;

sj1 = (j + 1 < height) ? j + 1 : j ;

for(i = 0; i < width; i+=2) {

si0 = i ;

si1 = (i + 1 < width) ? i + 1 : i ;

sum = pYUV[(si0 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 1] ;

sum += pYUV[(si1 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 1] ;

sum += pYUV[(si0 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 1] ;

sum += pYUV[(si1 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 1] ;

sum = sum / 4 ;

pYUV420[(si0 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 1] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si1 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 1] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si0 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 1] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si1 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 1] = sum ;

sum = pYUV[(si0 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 2] ;

sum += pYUV[(si1 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 2] ;

sum += pYUV[(si0 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 2] ;

sum += pYUV[(si1 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 2] ;

sum = sum / 4 ;

pYUV420[(si0 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 2] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si1 + sj0 * width) * 3 + 2] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si0 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 2] = sum ;

pYUV420[(si1 + sj1 * width) * 3 + 2] = sum ;

}

}

}

For every four luminance, we take all the four luminance values out. And then we take one Cr value and one Cb value from one scan line and in the next scan line, we don't take any samples.

Thus, when given an array of an image in the YUV420 format, each U or V components is used to represent 4 Y components.

In this algorithm, we keep the luminance values which is Y values of every pixel in YUV444, as for the chrominance values we chose the average chrominance values of four adjacent pixels which are the pixels in line i column j, line i column j+1, line i+1 column j and line i+1 column j+1.

Finally, we store all the data in the order of YUV and every four adjacent U or V values are the same. And then we use the function YUVtoRGB to show the image.

Run-length encoding (RLE) is a very simple form of lossless data compression in which runs of data (that is, sequences in which the same data value occurs in many consecutive data elements) are stored as a single data value and count, rather than as the original run.

Based on the basic concepts, the algorithm divides a 24-bit RGB image into three channels, the R channel, the G channel and the B channel, and performs RLE for each channel separately.

The principle of RLE is very simple and can be explained as follow: the key concept of RLE is reducing the physical size of a repeating string of characters. Run, which means the repeating string, is always encoded into two bytes. Run count is the first byte which represents the number of characters in run. The second byte, called run value, records the value of the characters in run. For instance, we require 15 bytes to store an uncompressed run of 15 A characters like AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA, while after compression by using RLE, only 2 bytes are enough to store 15A.

RLE is a very simple algorithm which is easy to understand and implement. It is the most useful way to compress the data that contains a lot of repeat values such as line drawings, binary image and so on.

unsigned char *CAppCompress::Compress(int &cDataSize) {

unsigned char *compressedData ;

cDataSize = width*height*3 ;

compressedData=new unsigned char[cDataSize*2];

int cSize=0;

unsigned short currentB = pInput[0],nextB,repeat = 1,currentG = pInput[1],nextG,currentR=pInput[2],nextR;

for (int i = 1; i<cDataSize/3;i++)

{

nextB=pInput[i*3];

if (nextB == currentB&&repeat<=127)

{

repeat=repeat+1;

if (i==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize]=repeat;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentB;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

else

{

compressedData[cSize] = repeat;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentB;

cSize=cSize+2;

currentB = nextB;

repeat = 1;

if (i==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize] = 1;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentB;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

}

GPosition=cSize;

repeat=1;

for (int i=1;i<cDataSize/3;i++)

{

nextG = pInput[i*3+1];

if (nextG == currentG && repeat<=127)

{

repeat=repeat+1;

if (i==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize] = repeat;

compressedData[cSize + 1] = currentG;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

else

{

compressedData[cSize] = repeat;

compressedData[cSize + 1] = currentG;

cSize=cSize+2;

currentG = nextG;

repeat = 1;

if (i==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize] = 1;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentG;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

}

repeat = 1;

RPosition=cSize;

for (int i=1;i<cDataSize/3;i++)

{

nextR=pInput[i*3+2];

if (nextR == currentR && repeat<=127)

{

repeat=repeat+1;

if (i ==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize]=repeat;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentR;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

else

{

compressedData[cSize]=repeat;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentR;

cSize=cSize+2;

currentR=nextR;

repeat=1;

if (i==(cDataSize/3-1))

{

compressedData[cSize]=1;

compressedData[cSize+1]=currentR;

cSize=cSize+2;

}

}

}

cDataSize = cSize;

return compressedData;

}

void CAppCompress::Decompress(unsigned char *compressedData, int cDataSize, unsigned char *uncompressedData) {

int repeat;

unsigned int b, g, r;

int i=0,j=0,p=0;

for (i=0,j=0;i<width*height,j<GPosition;j=j+2)

{

repeat = compressedData[j];

for (p=0;p<repeat;p++)

{

int d = compressedData[j+1];

uncompressedData[i*3+p*3+0]=compressedData[j+1];

}

i=i+repeat;

}

for (i=0,j=GPosition;i<width*height,j<RPosition;j=j+2)

{

repeat = compressedData[j];

for (p=0; p<repeat;p++)

{

int d = compressedData[j+1];

uncompressedData[i*3+p*3+1]=compressedData[j+1];

}

i=i+repeat;

}

for (i=0,j=RPosition;i<width*height, j<cDataSize;j=j+2)

{

repeat = compressedData[j];

for (int p=0;p<repeat;p++)

{

int d=compressedData[j+1];

uncompressedData[i*3+p*3+2]=compressedData[j+1];

}

i=i+repeat;

}

}

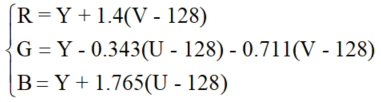

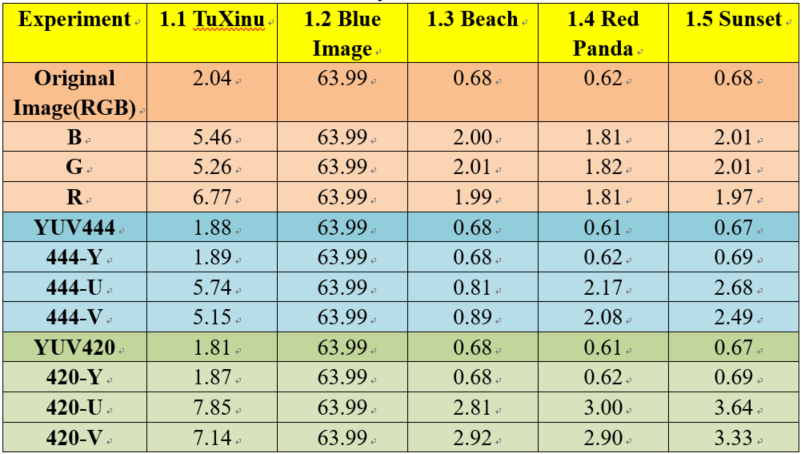

For explaining the compression results of different images, we’ve experimented several groups and compared them together. Scrupulously, all the images used in the following experiments are .jpg format.

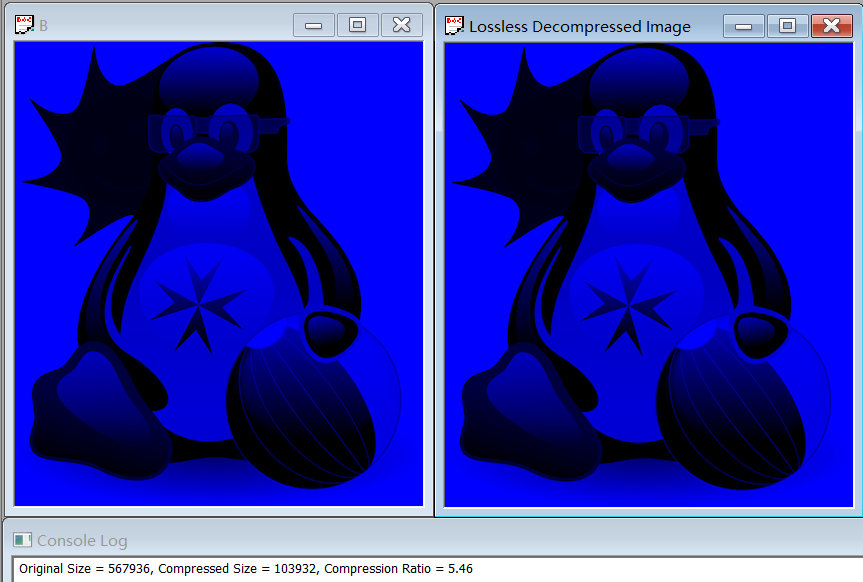

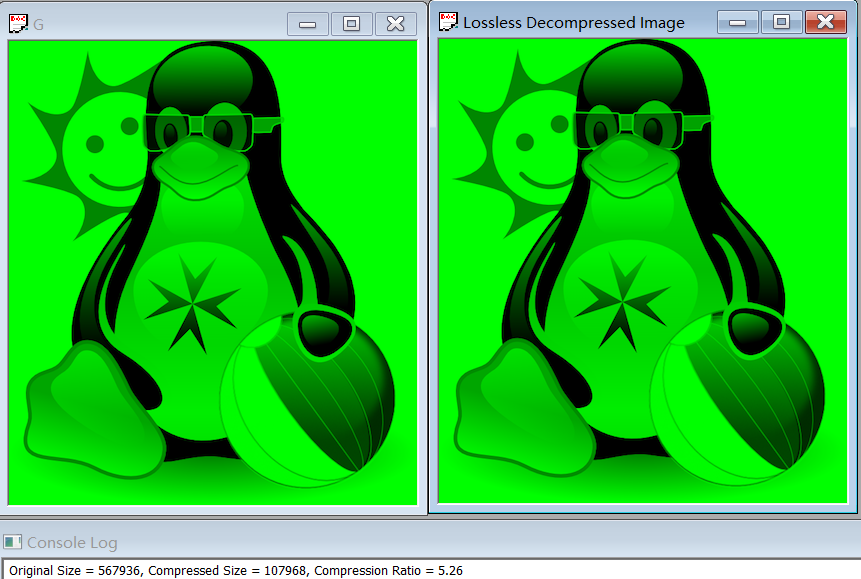

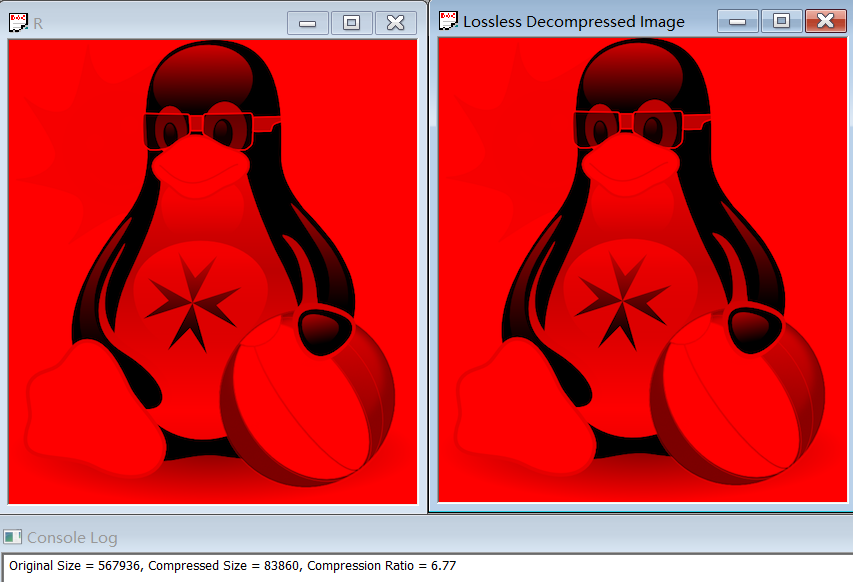

What’s more, besides the basic requirements for this experiment, we also compress the original RGB image separately in channel R, channel G and channel B to verify the relationship between different images by using C++.

In order to analysis the results better, 5 different kinds of images are used in this experiment. For each image, we operate original RLE compression, RGB to YUV444 and Y-, U-, V-channel compression, YUV444 to YUV420 and Y-, U-, V-channel compression, and original R-,G-, B-channel compresion.

The compression ratio is 2.04.

The compression ratio for YUV444 is 1.88, and for Y, U, V separately are 1.89, 5.74 and 5.15.

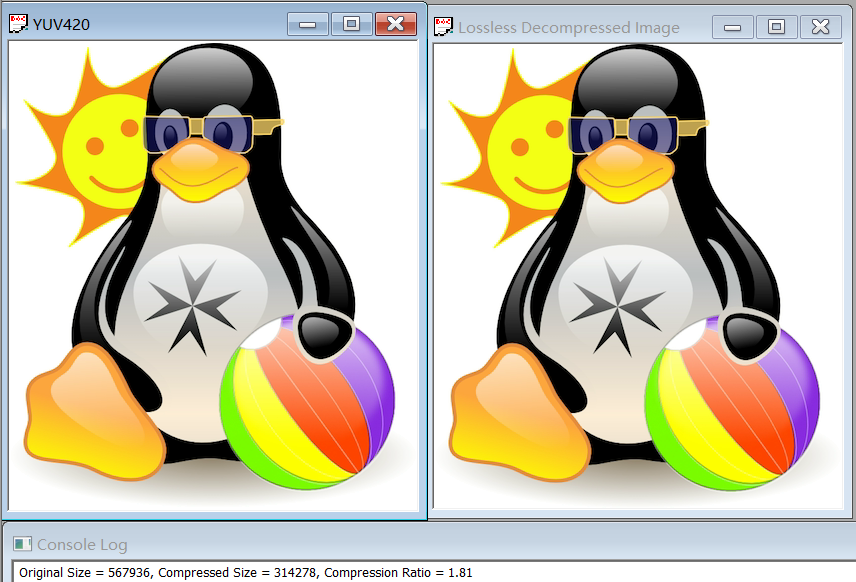

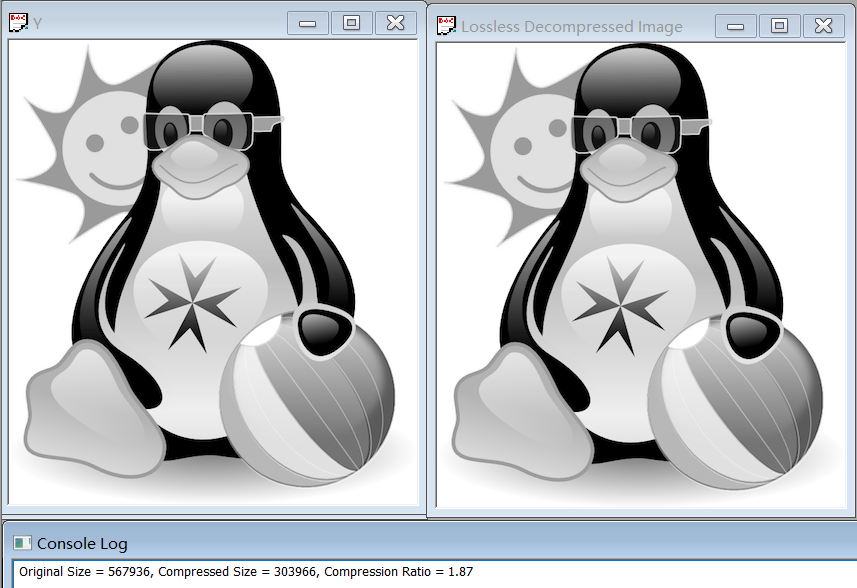

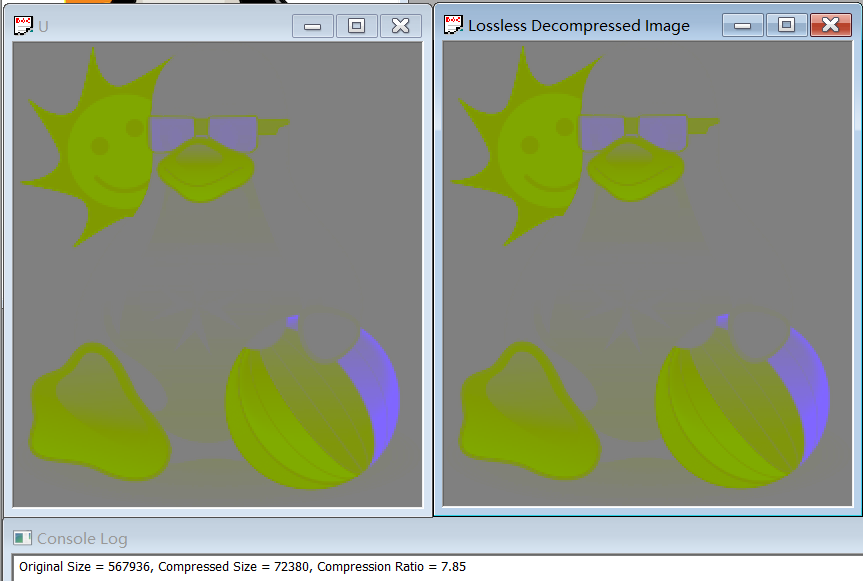

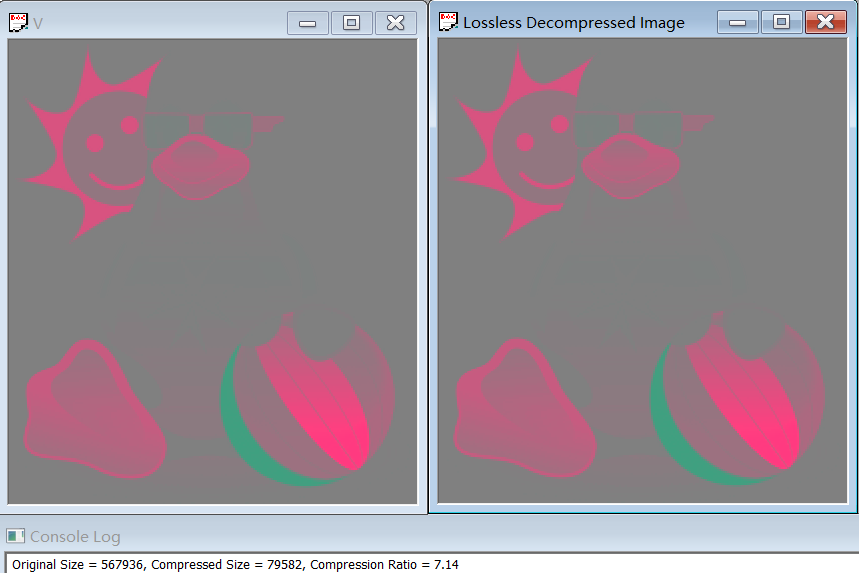

The compression ratio for YUV420 is 1.81, and for Y, U, V separately are 1.87, 7.85 and 7.14.

The compression ratio for B, G, R separately are 5.46, 5.26 and 6.77.

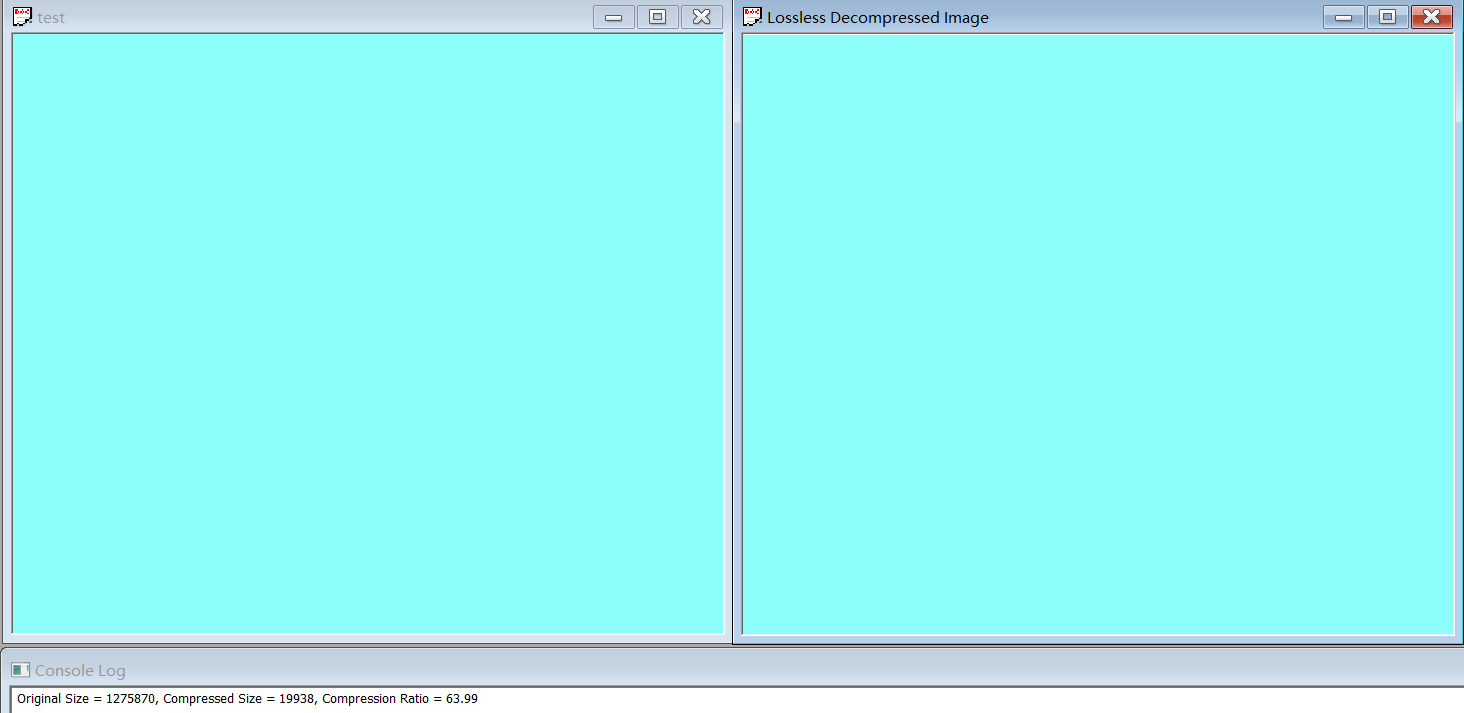

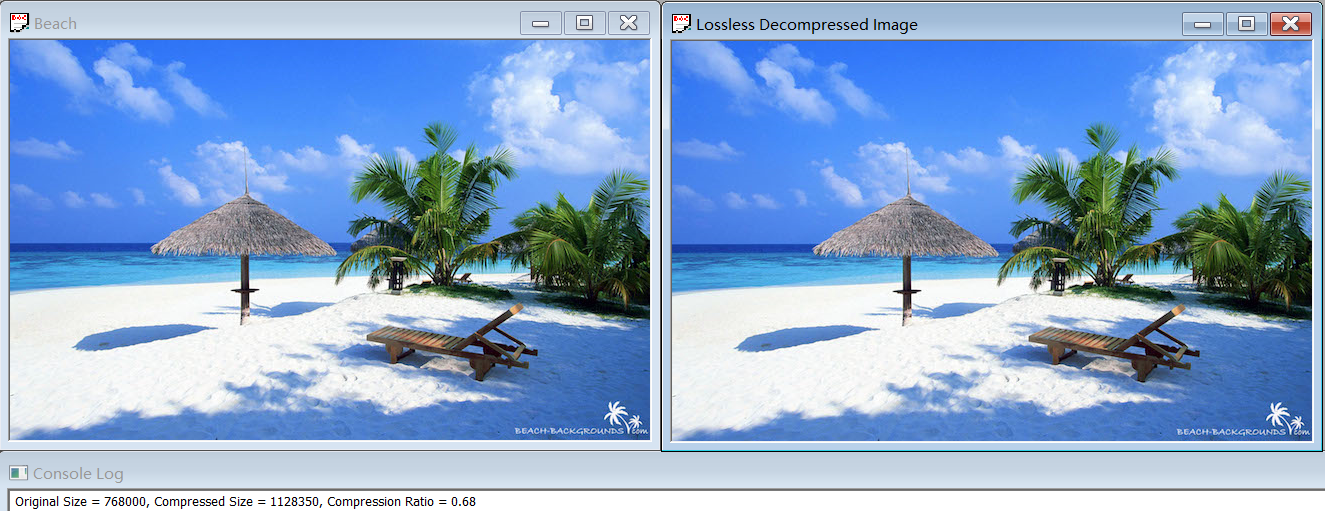

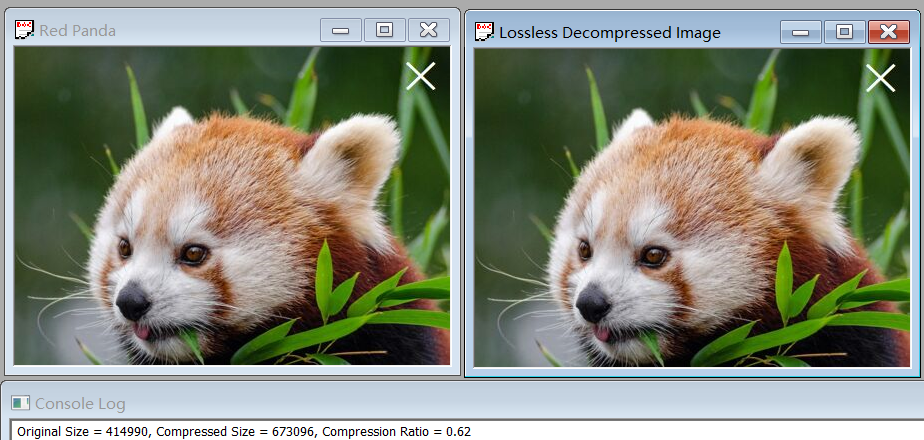

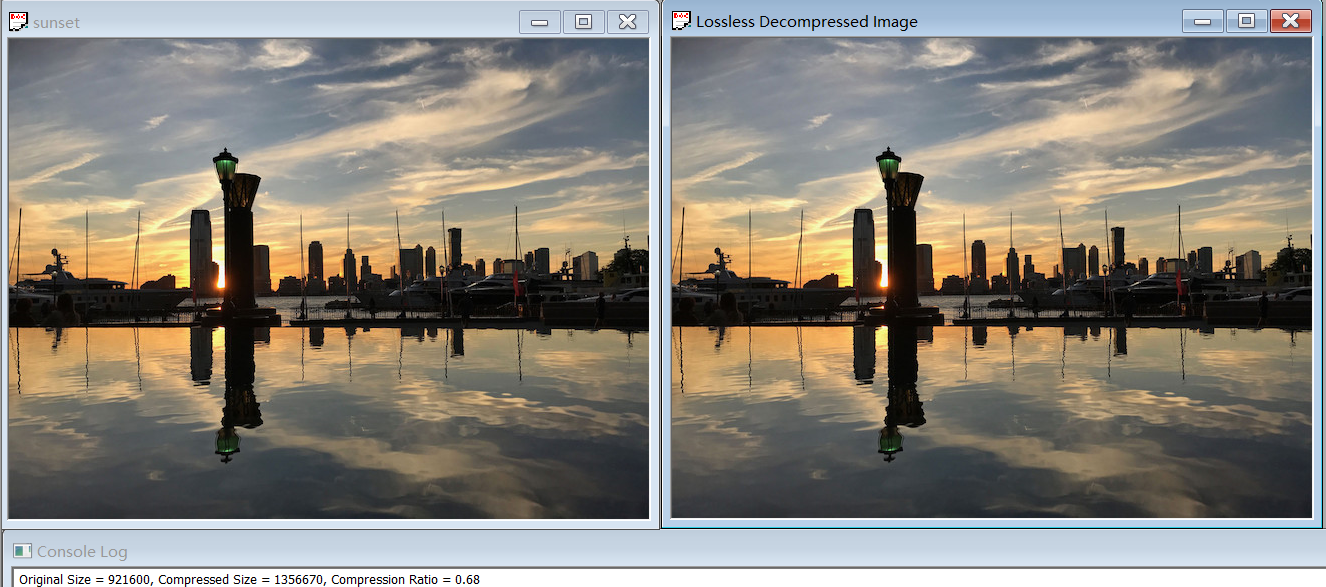

Experiment 2 to 5 are about other images. The specific steps are same as the first experiment, thus I do not write the details. The original and compressed images of experiment 2 to 5 are shown as below.

First, we organized all the compression ratio in experiments together by using the excel as follow to show the results clearly.

As we’ve explained, the key point of RLE is reducing the space of repetitive information. Thus, for image in experiment 1.1, it shows a penguin in white background. Comparing this image with others in experiment 1.31.5, it is obviously that this penguin image is simpler, which means it includes more repetitive information that can be compressed. Eventually, we can see the result shows that the experiment 1.1 has higher compression ratio than experiment 1.31.5.

This reason can also be proven by compare 1.1 with 1.2. In fact, the pure blue image in experiment 1.2 is designed as a control group in an extreme case. This image only has a single color, which means all the information in each pixel are same and can be compressed thoroughly. Thus, the compression ratio of experiment 1.2 is 63.99, which is much higher than others.

For the compression ratios in experiment 1.3~1.5, they are smaller than 1, which means the size of compression image is bigger than the original one. It can be explained by the principle of RLE. Since the information in pixels of these images are very different (it can be proved by the complexity of these images directly), it is hard for RLE algorithm to find the repetitive information while RLE needs a space to store the repetitive strings in addition. Based on this, the compression image needs more space to store than the original image.

For my perspective, it cannot regard the RLE as a “terrible” algorithm in image compression although some results may not ideally. Since it is hard to reduce the space with no information loss, the lossless compression can only do well in some simple situations such as process text, which contains more repetitive information than image.

In experiment 1.1, the compression ratio of RGB is higher than YUV. For other experiments, RGB and YUV have similar compression ratio, or RGB is a little bit higher than YUV. Based on this result. Thus, the RGB may does well than YUV for simple compression.

By comparing the compression ratio of channel R, channel G and channel B in each experiment, we can see that these three values are exactly similar. Since the RGB image is constituted by R, G, B equally and the compression ratio of R, G, B are similar, the totality compression ratio of RGB is higher than YUV. From another perspective, the compression result of YUV (both YUV444 and YUV420) are generally equal to channel Y, what we can see in the experiments’ result. For YUV, the channel Y represents the luminance information, which is the linear combination of channel R, G and B, while the value of channel U and channel V (or channel Cb and channel Cr) can be calculated by Y with B or R. Thus, the composition of Y is mainly influenced by the linear combination of R, G and B, a more complex situation than the composition of RGB. For RLE algorithm, the more complex composition means the less repetitive information, which results the lower compression ratio.

As we’ve analyzed in analysis 2, the compression ratio of YUV is mainly influenced by channel Y, while the channel U and channel V can be ignored in the mathematical analysis. Since the compositions of channel Y are same in YUV444 and YUV420, these two formats have the same compression ratio by using the RLE algorithm.

Since the YUV420 reduces the sampling rates in channel U and channel V while both U and V are not as important as channel Y in compression, the YUV420 can reduce the image resolution of U, V channels without image anamorphose seemingly. Thus, YUV420 has been widely used in daily life.