This post is ... discussion on performance considerations in implementation.

Every now and then some of my peers and I come up with random programming challenges for ourselves. This time the task was to write the fastest country code finder. That is, given a list of country codes and a collection of phone numbers, determine which country each phone number belongs to.

The country code is always the first few digits of the phone number. This is a type of string matching problem where we want to find the country code that is equal to the first few digits of the phone number. If a phone number matches multiple country codes then the longest match should be chosen.

The list of country codes used can be found at http://country.io/phone.json.

A few observations on the problem. First and foremost, both the country codes

and the phone numbers are numbers but that doesn't mean that we have use a

number type, such as int or long, to store them in memory. In fact, it is

most likely better to store them as strings. We're not interested in arithmetic,

we're doing string matching.

Both the country codes and the phone numbers are short. There are many string searching algorithms, but the ones I know about are designed for finding a search string somewhere in a long text. I this case we know where the sought string should be; at the very start. Moreover, we have many country codes to search for and also lots of phone numbers to search in.

An important observation is that the the set of country codes is constant throughout the application's lifetime. This means that whatever work we can do at startup to speed up the queries is worth it since the cost of the initial work will be amortized by the large number of queries. Within reason, of course.

There are a number of ways to approach this. Arguably, the simplest way is to

keep all the country codes as a list of strings and for each given phone number

loop over the country codes until a match is found. This works, but is probably

not very fast. It does O(c*d*p) digit comparisons where c is the number of

country codes, d is the average number of digits in a country code and p is

the number of phone numbers tested.

Note that the problem description dictate that we find the longest country code that matches. We should therefore sort the list by longest first so that we know that the first match is also the longest one.

Whenever we see a linear search through a collection of sortable elements we

should consider sorting the data and replace the linear search with a binary

one. This reduces the number of digit comparisons from O(c*d*p) to

O(log(c)*d*p). This is better, when testing a given phone number a whole slew

of country codes is not even looked at anymore. The d*p part may seem scary,

but remember that d is small and we do need to look at every digit of a country

code in order to accept or reject a potential match. I have not been able to

find a way around that.

While log(k) isn't too bad, we can do better still. A common way to do

constant time lookups is to use hashing. We insert each country code into a hash

table and for every given phone number we first test if the single digit prefix

substring can be found in the hash, then we test the leading two digits, and

then three and so on until we find a country code or the leading substring is

longer than the longest country code. This algorithm is O(d*p) digit

comparisons.

I have not been able to find or come up with something better than O(d*p), but

I have found an alternative data structure that gives the same O. A

Trie, also called a prefix tree, is a tree

used to store data where the location in the tree, i.e., path from the root to

the containing node, defines the key that the data it associated with. An

example is in order.

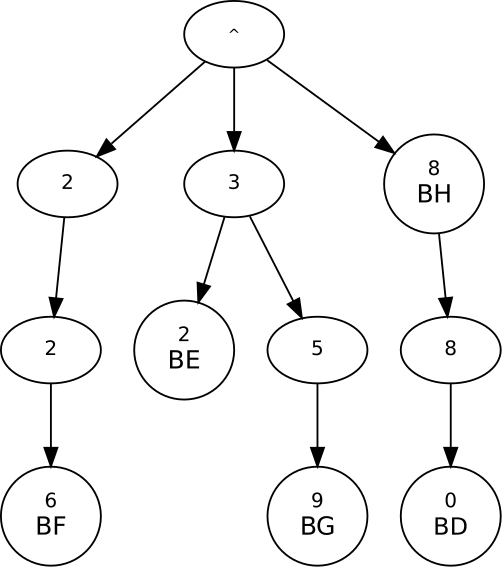

Assume that we are given the following country codes:

- "BD": "880"

- "BE": "32"

- "BF": "226"

- "BG": "359"

- "BH": "8"

This is the resulting trie:

A few things to note. First, the root node contains "^", which is used to denote the start of a string. Secondly, data may appear not only in the leave nodes, but in internal nodes as well. Third, some nodes doesn't contain any data. They exist only to define the path to the data contained in the node's children. Lastly, to find the country code of a number we walk down the trie as dictated by the first few digits of the number and stop as soon as we find a non-empty node.

Caches are all the rage these days. The ever widening processor-memory performance gap is making memory accesses more and more expensive in terms of CPU cycles. This has made cache-friendly access patterns more important than ever. I will discuss the memory access patterns for each implementation strategy later in this text.

However, in addition to the access patterns, the size of the working set must be taken into account as well. The input file, http://country.io/phone.json, is 3.3 KB and it is reasonable to believe that storing the data in memory will use a comparable amount of space. The CPU I'll be testing on has 16 KB of L1 data cache per core. This means that we can put the entire data set into L1 cache and still have plenty of room left for whatever acceleration structure we choose.

When striving for the fastest possible implementation it is important to identify unspecified details in the problem description and chose whatever interpretation that allows for the fastest implementation. In this case I have made the following assumptions:

- If a phone number matches multiple country codes of equal length, then any

one of them may be returned.

- All phone numbers have the the same length, 8 digits.

- Phone numbers may be created randomly.

The linear search algorithm is implemented in LinearSearch.cpp and is as

straightforward as it gets. A vector contains the (country code, country id)

pairs, sorted by code length, and a number lookup simply iterates over the

vector and for each country compares the current phone number with the country

code digit by digit until the first match is found.

Central to this method is the implementation of

bool startsWith(char const * number, std::string const & code)Signature of code testing function.

which determines if a given number starts with the given country code. We

start with the most natural implementation, which is a call to std::mismatch.

This is a standard library function that returns the point at which two ranges

first differ. In our case it tells us where the number no longer matches the

country code. If the algorithm is unable to find any mismatch then the country

code is a prefix of the number and we have found our country.

auto mismatchPoint = std::mismatch(begin(code), end(code), number);

return mismatchPoint.first == end(code);Implementation using the standard library method mismatch.

Trying to improve upon the standard library implementation, we write the digit

testing loop manually. First using a for each loop:

for (auto c : code) {

if (c != *number)

return false;

++number;

}

return true;Implementation using a for each loop over the digits of the code.

and secondly we implement this loop in a C style fashion as follows.

char const * c = code.c_str();

while (*c != '\0' && *c == *number) {

++c;

++number;

}

return *c == '\0';Implementation using C construct only.

These three implementations are very similar. They all use the end of code as

their stop condition, they must all increment the number pointer on every

iteration, and they all do a char comparison as an early-exit condition. One

might expect that they would perform equally.

They didn't.

Let's figure out why. First up is perf stat.

Performance counter stats for './mismatch':

60,477683 task-clock:u (msec) # 0,991 CPUs utilized

0 context-switches:u # 0,000 K/sec

0 cpu-migrations:u # 0,000 K/sec

121 page-faults:u # 0,002 M/sec

223 195 029 cycles:u # 3,691 GHz (80,17%)

17 145 522 stalled-cycles-frontend:u # 7,68% frontend cycles idle (80,16%)

29 415 275 stalled-cycles-backend:u # 13,18% backend cycles idle (40,64%)

421 523 844 instructions:u # 1,89 insn per cycle

# 0,07 stalled cycles per insn (55,22%)

90 662 947 branches:u # 1499,114 M/sec (68,44%)

2 856 340 branch-misses:u # 3,15% of all branches (81,67%)

0,061041527 seconds time elapsed

Performance counter stats for './for_each':

172,374141 task-clock:u (msec) # 0,998 CPUs utilized

0 context-switches:u # 0,000 K/sec

0 cpu-migrations:u # 0,000 K/sec

121 page-faults:u # 0,702 K/sec

657 547 329 cycles:u # 3,815 GHz (83,65%)

287 710 712 stalled-cycles-frontend:u # 43,76% frontend cycles idle (83,78%)

7 485 469 stalled-cycles-backend:u # 1,14% backend cycles idle (33,08%)

308 331 340 instructions:u # 0,47 insn per cycle

# 0,93 stalled cycles per insn (49,33%)

69 781 078 branches:u # 404,823 M/sec (65,57%)

2 822 864 branch-misses:u # 4,05% of all branches (81,80%)

0,172803061 seconds time elapsed

From top to bottom. task-clock is the amount of wall clock time that the

process was on the CPU. It is expected to be higher than the timing measurements

done by the application itself since the task-clock time also includes the

startup time. Next is context-switches and cpu-migrations. We're running a

really short program on a lightly loaded machine, so we expect both of these to

be zero.

Page faults are costly, so we really want to minimize them. In fact, our memory working set is so small that I don't see why we would get any at all, once the number processing has started. So why 121? A sure source of page faults is the loading of the application itself. How many page faults should we get by simply loading the application into memory? The size of the binaries on disk is 370K and with a page size of 4k we would get 95 page faults. The remaining 26 are probably from loading various libraries due to the usage of the standard library and from the initial setup done by the application. 121 page faults seems reasonable.

Another way to verify that the main loop doesn't trigger any page faults is to increase the number of phone numbers tested.

Performance counter stats for './mismatch_100k':

121 page-faults:u

0,064132723

Performance counter stats for './mismatch_500k':

121 page-faults:u

0,840972279 seconds time elapsed

We see that the wall time increased but the page faults did not, thus the main loop is page fault free.

A third way is to use a profiler to record where the page faults happen. We can

use perf record for this. I run perf with perf record -c 1 -e page-faults -g ./mismatch to capture the call stack (-g) to every (-c 1) page fault (-e page-fault) when running ./mismatch. Viewing the results with perf report -n lists a whole bunch of _dl_sysdep_start, _dl_relocate_object,

_dl_map_object, and similar. That's the loading alright. Digging in a bit

deeper, into the annotated assembly, I find three page fault in fillCountries,

one in the random number generator constructor, one in the random data filler

and one in the random number generator. The first and the last two are expected

since they all, the first time they run, process a bunch of newly allocated

memory. The one in the constructor happens, I believe, because the on-stack

allocation of the Random object causes the stack to grow past a page boundary.

The details are unclear. The Random class contains an internal buffer of

random bytes that is pre-fills. This buffer is 2048 * 4 = 8192 bytes, or 2

pages. Thus filling it must generate at least two page faults. Most likely it

won't be page boundary aligned so we'll get three, as was reported by perf.

The std::vector holding the country data contains 246 elements each requiring

40 bytes. This totals 9840 bytes, which is a bit over two pages. The three page

faults in fillCountries are thus explained.

Next in the perf output is cycles. The run using std::mismatch measured

223,195,029 cycles while the one using the for-each loop used 657,547,329. Since

the application is heavy on computation and does very little IO the cycle count

is basically a measure of time. The large difference is expected since the

application timers reported lower throughput for the for loop, and therefore it

consumes more cycles, but perf doesn't give any hints as to why that is.

Next up is stalled-cycles-frontend and here we get to the interesting part.

The std::mismatch version has 17,145,522 stalled cycles which perf report as

7.68% of all cycles. The for-each version has 287,710,712, or 43,76%, cycles

stalled in the front end. That's significant. If correct, the CPU is doing

nothing almost half of the time. There are a number of reasons for why the CPU

may stall. It may be waiting for the next instructions to be loaded from memory,

a long-latency instruction to finish, or for a data dependency to be resolved.

Inspecting the assembly may provide some answers. The following two listings are

taken from perf report after recording stalled-cycles-frontend events using

perf. Each row represents an instruction in the program binary. The first

column is the number of stalled-cycles-frontend samples taken at that

instruction, the second column, which is mostly empty, are byte offsets used by

jump instructions. The third column is the instruction itself and what remains

on the row are the arguments to the instruction.

Inner loop, mismatch:

121 │250:┌─→movzx ebx,BYTE PTR [rdx+rbp*1]

418 │ │ movzx edi,BYTE PTR [rax+rbp*1]

32 │ │ cmp edi,ebx

│ │↓ jne 270

21 │ │ inc rbp

418 │ │ cmp rcx,rbp

│ └──jne 250

│ ↓ jmp 290

Inner loop, for_each:

5724 │250:┌─→movzx ebx,BYTE PTR [rdx+rbp*1]

7785 │ │ movzx r15d,BYTE PTR [rax+rbp*1]

│ │ cmp r15d,ebx

│ │↓ jne 270

133 │ │ inc rbp

921 │ │ cmp rcx,rbp

│ └──jne 250

4 │ ↓ jmp 280

Both surprisingly and unsurprisingly, they are virtually identical. Unsurprisingly because that was our initial guess. They do the same work, so why would different instructions be generated? Surprisingly because we see so very different performance characteristics.

A walkthrough of the code snippets. Remember the original C++ code.

auto mismatchPoint = std::mismatch(begin(code), end(code), number);

return mismatchPoint.first == end(code);Implementation using the standard library method mismatch.

for (auto c : code) {

if (c != *number)

return false;

++number;

}

return true;Implementation using for-each loop.

They both start with loads of a pair of bytes from memory into a pair of

registers. This is loading c and the dereferencing of number in the C++

code. The mismatch version loads into ebx and edi, while the for-each

version loads into r15d instead of edi. All general purpose registers, so I

don't see any reason for a performance difference yet. rdx and rax, used in

the address calculation, presumably holds pointers to the starts of the two

strings we are comparing, and rbp holds the index of the characters we are

currently comparing. After the loads the two newly filled registers are compared

using cmp and if not equal we jump (jne) out of the loop. This is the if (c != *number) return false part of the C++ code. Next rbp is incremented. Since

rbp is used in both loads, this single instruction does both the increment of

number and the iterator increment hidden inside the for-each loop header.

After the increment a second comparison is made. This comparison tests if rbp

has reached the end of the string, which was, presumably, previously stored in

rcx. If not equal, i.e., there are more characters to test, then the program

jumps back to the start of the loop.

Since the generated assembly code is so similar between the two version, the reason for the performance difference must lie somewhere else.

Let's expand the assembly listing a bit. To understand the following we first

need to take a look at the surrounding C++ code. The method containing the inner

loop is called from a method named getCountry:

CountryId getCountry(char const (&number)[9]) {

for (auto & country : m_countries) {

if (startsWith(number, country.code)) {

return country.id;

}

}

return not_found;

}getCountry

CountryId is a struct containing a two element char array and not_found is a

constexpr CountryId having '\0' in both array slots. This is the part of the

code that makes this implementation a linear search.

getCountry is called from main in a loop with the following layout:

for (int i = 0; i < numIterations; ++i) {

common::genrateNumbers(numbers, random);

for (auto const & number : numbers) {

CountryId country = phoneBook.getCountry(number);

if (country.id[0] != 0) {

++numMatches;

}

}

}Main loop

In the above, numbers is declared as std::array<char[9], numbersPerIteration> numbers;, numIterations is 100 and numbersPerIteration is 1000. That is,

for each outer iteration we first generate a thousand phone numbers and then

check them one by one. We do this one hundred times. The second argument to

generateNumbers, random, is a pseudo-random number generator that is

discussed in a separate section.

mismatch:

│ mov r8,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x4350] // Load 8 bytes from memory. two pointers to 8 Is this the

1 │ mov r13,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x4358] // Load 8 bytes from memory. byte values perhaps? std::array?

│ cmp r8,r13 // Check if the two values just loaded are equal.

│ lea rdx,[rsp+0x2028] // Load a completely different value from memory.

│ ↓ jne 230 // lea sets no flags, so jne for r8, r13.

│223:┌─→movzx eax,BYTE PTR [r11+0x20] // Was r8, r13 was equal. Load a byte from memory.

│ │↓ jmp 295 // Jump past loop.

│ │ nop // NEVER REAHCED.

│230:│ mov r11,r8 // Copy r8 (pointer?) to r11.

47 │233:│ mov rax,QWORD PTR [r11] // Dereference the pointer. rax = *r11.

6 │ │ mov rcx,QWORD PTR [r11+0x8] // Dereference the pointer. rcx = *(r11 + 1)

│ │ test rcx,rcx // Did the second dereference find a zero?

79 │ │ mov ebp,0x0 // ebp = 0.

52 │ │ mov r14,rax //

2 │ │↓ je 276

│ │ nop

129 │250:│ movzx ebx,BYTE PTR [rdx+rbp*1]

390 │ │ movzx edi,BYTE PTR [rax+rbp*1]

29 │ │ cmp edi,ebx

│ │↓ jne 270 // Found mismatched character, return false.

26 │ │ inc rbp

440 │ │ cmp rcx,rbp

│ │↑ jne 250

│ │↓ jmp 290

│ │ nop

93 │270:│ add rbp,rax

111 │ │ mov r14,rbp

42 │276:│ add rax,rcx

3 │ │ cmp r14,rax

88 │ └──je 223

70 │ add r11,0x28

89 │ cmp r11,r13

37 │ ↑ jne 233

│ xor eax,eax

│ ↓ jmp 295

│ nop

38 │290: movzx eax,BYTE PTR [r11+0x20]

3 │295: cmp al,0x1

│ sbb r15d,0xffffffff

│ add rdx,0x9

│ cmp rdx,r10

│ ↑ jne 230

│2a4: inc r9d

1 │ cmp r9d,0x64 // 0x64 == 100. We do 100 generate-test iterations.

│ ↑ jne e0 // Restart outermost loop, i.e., generate a new set of numbers.

The implementation uses std::string for storing the country codes. This may be

sub-optimal since std::string stores its data on the heap and because of this

moving from from one country code to the next results in a random jump in

memory. Fortunately, country codes are short and we therefore benefit from the

small string optimization that is provided by many standard library

implementations. Different implementations have made different decisions on what

constitutes a small string, but according to

http://info.prelert.com/blog/cpp-stdstring-implementations the limit is at least

15 characters for the most common implementations. Our phone numbers are only 8

digits and the country codes are even shorter, so we're good.

We can save a few bytes per string by rolling our own packed string array

format. A std::string is 32 bytes on my compiler and the average country code

length is about 3 bytes, but I doubt it will make linear search competitive with

the other algorithms.

To allow for binary search through a data set the data must be ordered so that we can look at any element and determine on which side of that element the sought element must reside. In our case a regular alphabetical ordering achieves just that. One complicating factor is that a phone number may match several country codes and we must find the longest one. But the alphabetical sorting will at least place all such country codes next to each other so when the first match is found we can do a linear search forward for the last code that matches.