One sentence summary:

You can use English text data to improve Indonesian text classification performance using a multilingual language model.

This repository is my final year undergraduate project on Institut Teknologi Bandung, supervised by Dr. Eng. Ayu Purwarianti, ST.,MT. It contains the unpolished source codes (.py on /src and .ipynb on /notebooks), book (Indonesian), and paper (English).

-

Book title:

Klasifikasi Teks Berbahasa Indonesia Menggunakan Multilingual Language Model (Studi Kasus: Klasifikasi Ujaran Kebencian dan Analisis Sentimen) -

Paper title (Arxiv):

Improving Indonesian Text Classification Using Multilingual Language Model

├── README.md <- The top-level README

├── data <- Contain information regarding the data

├── docs

| ├── book <- Latex source for the book

| └── paper <- Microsoft word source for the paper

|

├── notebooks <- The *.ipynb jupyter notebooks

| ├── fine_tune_full <- Notebooks for full finetune experiments

| ├── fine_tune_head <- Notebooks for feature-based experiments

| └── result_analysis <- Notebooks analyzing and producing figures

|

└── src <- The *.py source code

Compared to English, the amount of labeled data for Indonesian text classification tasks is very small. Recently developed multilingual language models have shown its ability to create multilingual representations effectively. This paper investigates the effect of combining English and Indonesian data on building Indonesian text classification (e.g., sentiment analysis and hate speech) using multilingual language models. Using the feature-based approach, we observe its performance on various data sizes and total added English data. The experiment showed that the addition of English data, especially if the amount of Indonesian data is small, improves performance. Using the fine-tuning approach, we further showed its effectiveness in utilizing the English language to build Indonesian text classification models.

The experiments consist of two multilingual language model (mBERT [1] & XLM-R [2]), three training data scenarios, two training approaches, and five datasets. Every experiment was run on Kaggle kernel. You can find the link to every Kaggle's kernel & datasets on each directory.

We investigate the model performance in three different scenarios. Each differs by the combination of the language used in its training data: monolingual, zero-shot, and multilingual. In the monolingual scenario, we use the Indonesian language text to train and validate the model. In the zero-shot scenario, we use the English language text to train the model while being validated on Indonesian text. Lastly, we use a combination of Indonesian and English text to train the model while being validated on Indonesian text in the multilingual scenario. Using these scenarios, we observe the improvement of the added English text.

There are two approaches on applying large pre-trained language representation to downstream tasks: feature-based and fine-tuning [1]. On the feature-based approach, we extract fixed features from the pre-trained model. In this experiment, we use the last hidden state, which is 768 for mBERT and 1024 for XLM-R Large, as the feature. This extracted feature is then fed into a single dense layer, the only layer we trained on the feature-based approach, connected with dropout before finally ending on a sigmoid function. In contrast, the finetuning approach trains all the language model parameters, 110M for mBERT and 550M for XLM-R Large, including the last dense layer, on the training data binary cross-entropy loss.

Using the feature-based scenario, we run many experiments as the expensive and multilingual representation have been precomputed on all the data. In all training data scenarios, we vary the total data used. More specifically, we train the model using [500, 1000, 2500, 5000, 7500, Max] text data. Specific to multilingual training data scenario, we vary the amount of added English data by [0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] times the amount of Indonesian text data. We refer to a multilingual experiment with added English data N times the amount of Indonesian text data as multilingual(N).

In contrast to the feature-based scenarios, fine-tuning the full language model is expensive and resource-intensive. However, as shown in [1], fully fine-tuning the full language model will result in a better text classifier. We fine-tuned the best performing model on the feature-based scenarios. The experiment was reduced to only using the maximum total data and an added English data multiplier up to 3.

More details on the book and paper. Quick summary:

-

Indonesian:

- Sentiment Analysis 1: (Farhan & Khodra, 2017) [3]

- Sentiment Analysis 2: (Crisdayanti & Purwarianti, 2019) [4]

- Hate-speech and Abusive: (Ibrohim & Budi, 2019) [5]

-

English:

- Sentiment Analysis: Yelp Review Sentiment Dataset

- Toxic Comment: Jigsaw Toxic Comment

We split the training data into training and validation set with a 90:10 ratio. The split was done in a stratified fashion, conserving the distribution of labels between the training & validation set. The result is a dataset separated into training, validation, and test sets.

Each experiment will train the model using the training set and validate it to the validation set on each epoch. After each epoch, we will evaluate whether we will continue, reduce the learning rate, or stop the training process based on validation set performance and the hyperparameter set on each condition. In the end, we use the model from the best performing epoch based on its validation performance to predict the test set.

On the feature-based experiment, we set the final layer dropout probability to 0.2, the learning rate reducer patience to 5, and the early stopping patience to 12. On full fine-tune experiment, we set the final layer dropout probability to 0.2, the learning rate reducer patience to 0, and the early stopping patience to 4. Every validation and prediction use 0.5 as its label threshold.

To ensure reproducibility, we set every random seed possible on each experiment. On the feature-based experiment, we average the result of 6 different runs by varying the seed from 1-6. Running the same experiment on the feature-based approach will result in the same final score. On the full fine-tune experiment, we only run one experiment. While the result should not differ substantially, the exact reproducibility cannot be guaranteed as the training was done on a TPU.

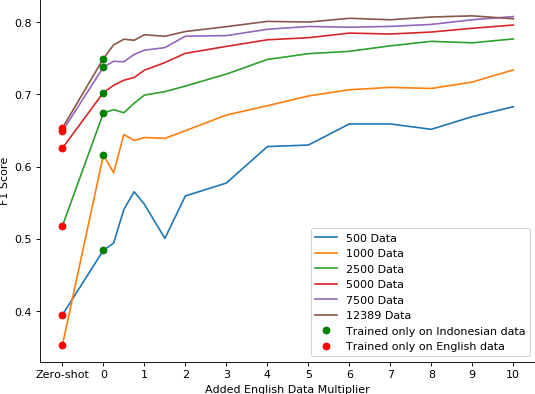

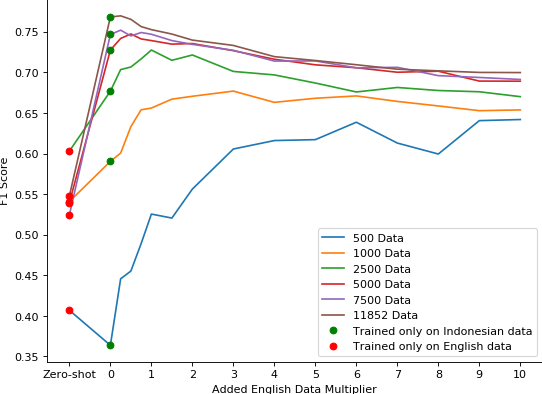

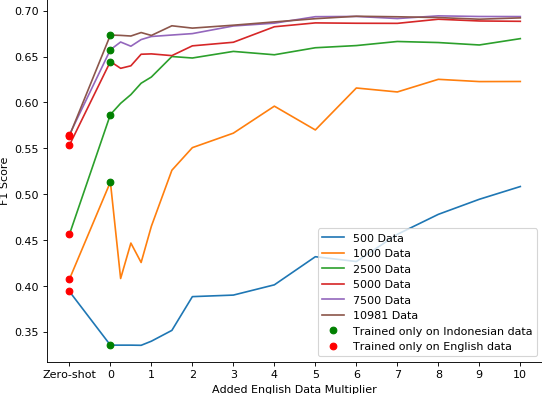

Fig. 1. Feature-based experiment result with XLM-R on [3] (left), [4] (middle), and [5] (right)

The result of feature-based experiments with XLM-R model on all datasets can be seen in Fig 1. Through this result, we can see that adding English data can help the performance of the model. On [3] & [4] dataset, adding English data consistently improves the performance. But on [5] dataset, there's a point where the added English data results in worse performance. We hypothesize this is due to the large difference in what constitutes hate-speech (or toxic by Jigsaw dataset) between the datasets used.

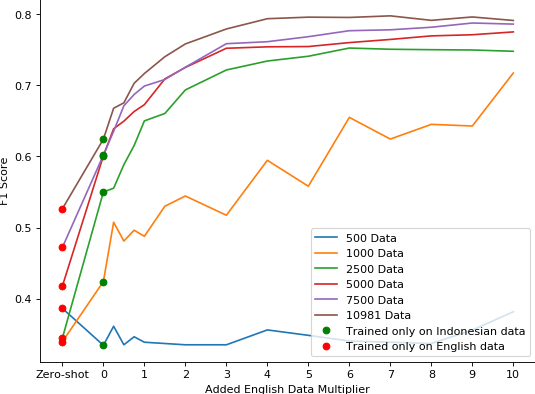

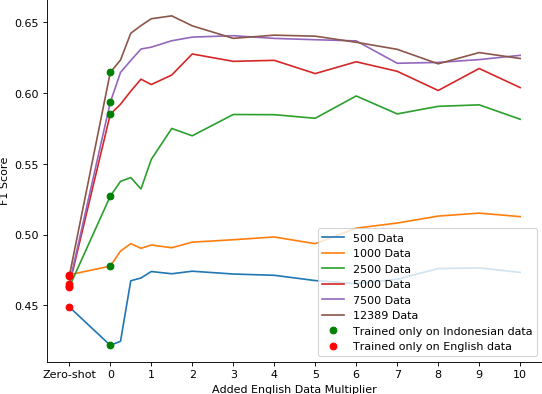

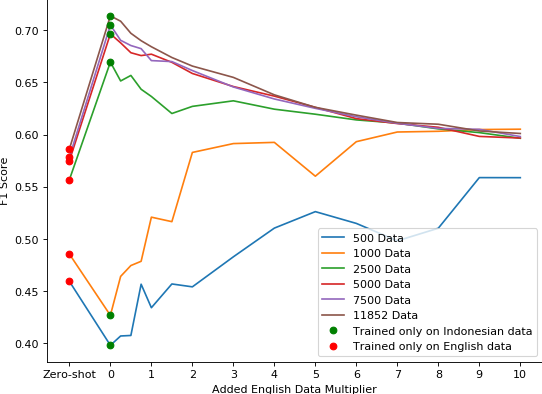

Fig. 2. Feature-based experiment result with mBERT on [3] (left), [4] (middle), and [5] (right)

The result of feature-based experiments with mBERT model on all datasets can be seen in Fig 2. The same phenomenon is observed on mBERT based experiment, although the performance is substantially lower. This is expected as XLM-R is designed to improve mBERT on various design choices.

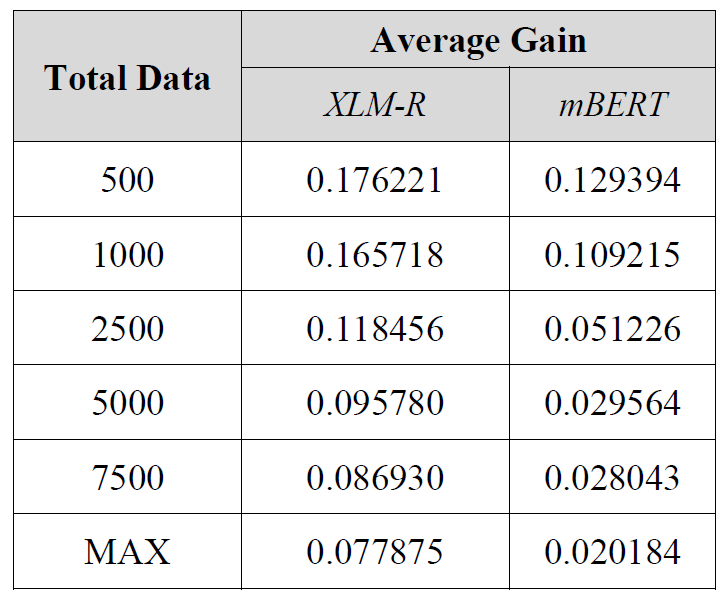

Defining the gain as the difference between monolingual and its highest multilingual performance, Table I shows the gains averaged on all datasets across total data and model. The highest gain can be seen on the lowest amount of total data used, 500, with F1-score gain of 0.176 using XLM-R model and 0.129 using mBERT model. The results suggest that the lower the amount of data used; the more gains yield by adding English data to the training set.

Table I. Average F1-Score Gains

The result of fully fine-tuning all parameters, in addition to utilizing English data, proved to be effective in building a better Indonesian text classification model. On [3] dataset, the highest performance achieved on the zero-shot scenario where it yielded 0.893 F1-score, improving the previous works of 0.834. On [4] dataset, the highest performance achieved on multilingual(1.5) scenario where it yielded perfect F1-score, improving the previous works of 0,9369. On [5] dataset, the highest performance achieved on multilingual(3) scenario where it yielded 0.898 F1-score and 89.9% accuracy. To provide a fair comparison with the previous work by Ibrohim & Budi [5], we also ran the experiment using the original label and monolingual scenario. The experiment yielded 89.52% average accuracy, improving the previous works of 77.36%.

Research mentioned in this README:

[1] J. Devlin et al. “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”. In: arXiv:1810.04805 [cs] (2019). arXiv: 1810.04805. URL: http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805.

[2] A. Conneau et al. “Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale”. In: arXiv:1911.02116 [cs] (2020). arXiv: 1911.02116. URL: http://arxiv.org/abs/1911.02116.

[3] A. N. Farhan & M. L. Khodra. “Sentiment-specific word embedding for Indonesian sentiment analysis”. In: 2017 International Conference on Advanced Informatics, Concepts, Theory, and Applications (ICAICTA). 2017, 1–5. DOI: 10.1109/ICAICTA.2017.8090964.

[4] I. A.P. A. Crisdayanti & A. Purwarianti. “Improving Bi-LSTM Performance for Indonesian Sentiment Analysis Using Paragraph Vector”. In: (2019).

[5] M. O. Ibrohim & I. Budi. “Multi-label Hate Speech and Abusive Language Detection in Indonesian Twitter”. In: Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Abusive Language Online. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, 46–57. DOI: 10 . 18653 / v1 / W19 - 3506. URL: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W19-3506.