-

Competition overview: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/stanford-ribonanza-rna-folding/overview

-

Data: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/stanford-ribonanza-rna-folding/data

This repository is set up to reproduce two of my solutions to the competition. For more details on the code, see Notes on the code section.

The notebook published by Iafoss [1] was my starting point. I used transformer architecture in this competition. Here are the details of the generated submissions that might have contributed to the result:

- In addition to sequence itself, I used minimum free energy (MFE) RNA secondary structure in dot-parentheses notation. For some experiments, I also calculated base pair probability matrices (BPPs), however, the best-scoring submission did not use them. Both MFE and BPPs were obtained via EternaFold package [2].

- Position information is encoded via rotary embeddings [3] in the best-scoring submission. Some other experiments use both rotary and sinusoidal embeddings.

- Sequences and MFE indices always have end-of-sequence (EOS) token appended at the beginning and at the end.

- Sequences and MFE indices are padded from both sides so that the middles of all RNA molecules enter the model at roughly the same position.

- One model makes two types of predictions: DMS_MaP and 2A3_MaP.

The best model achieved 0.15867 MAE on private and 0.15565 MAE on public leaderboard. I will refer to this submission as "submission-27" for historical reasons.

"Submission-23" was the second submission I chose for evaluation, with 0.17211 private and 0.15363 public MAE score.

The submission with the best public score was not chosen for evaluation because the model does not generalize well, as per "How to check if your model generalizes to long sequences" discussion.

The model for "submission-27" consists of one decoder layer as the first layer and eight BERT-like encoder layers on top.

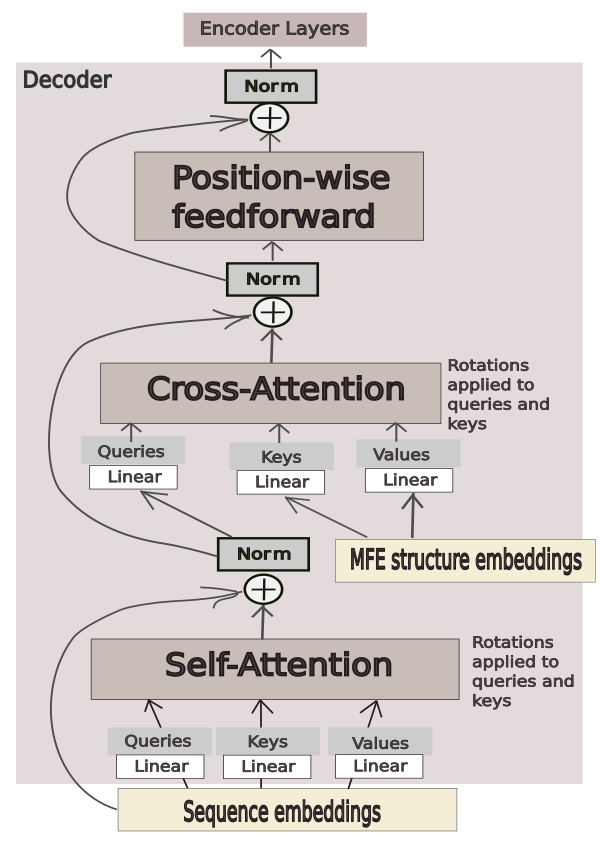

The decoder layer accepts sequence embeddings as "target" and MFE-structure embeddings as "memory" (information that would be coming from an encoder in a traditional encoder-decoder transformer). A mask that prevents the decoder from attending to padding tokens is applied. Other than masking the padding tokens, no other mask is applied, and the decoder is able to attend to all information it receives. A schematic presentation of how the information flows through the decoder is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The flow of information through the decoder layer for "submission-27".

Rotary embeddings are used in every attention module inside the model.

The model for "submission-23" consists of two decoder layers accepting sequence embeddings together with additional information and eight BERT-like encoder layers on top.

The first decoder layer receives embedded sequences (sinusoidal embeddings are used from the starter notebook) and performs self-attention in the standard manner. After the addition and normalization, another attention-related matrix multiplication is performed where BPPs are used as attention scores, followed by the position-wise feedforward layer.

The second decoder layer is analogous to the decoder depicted in Figure 1. However, instead of sequence embeddings it receives the output from the first decoder layer.

Thus, the first decoder layer uses BPPs and the second decoder layer uses MFE structure as additional information. More details on the architecture can be found in the code.

The training procedure was adapted from the starter notebook [1].

The training was performed for 45 epochs on "Quick_Start" data (after some processing) for both "submission-27" and "submission-23". Model were saved after each epoch. The last model was picked for "submission-23" and the model after 28 epochs for "submission-27".

I used sequences that were not in "Quick_Start" data as validation data. These sequences were filtered out based on error values.

This repository is set up to reproduce two of my solutions: "submission-27" and "submission-23". It is possible to run these scripts on a system with one GPU (10 GB of memory), 20 CPUs, and 128 GB RAM. Without BPPs (reproducing "submission-27" only), the RAM requirement is 64 GB. More specific details are in "note_on_requirements.txt".

This repository is not the original code I used for my experiments. The original code includes all earlier experiments and is more difficult to follow. The code in the current repository is organized in a step by step fashion. Some steps (step 3 and 4) need to be re-run twice: for training and for validation data separately.

The overall idea was to pre-process the training (and validation) data with maximum extraction of information: all data-related calculations should be done during this step. The resulting dataframe is saved into storage. During training, this dataframe is read from the storage and all columns that are unnecessary for a specific experiment are dropped. This setup allows a great flexibility in designing experiments. Ideally, the test data should be processed in a similar way, but I did not have enough time.

Step 1: The script processes training data and saves it as a parquet file. However, after this step the data is not ready to use. This is only an "intermediate" step in data processing. In this step, I create one dataframe where each row carries information about both types of reactivity. Sequences are not processed in this step.

Step 2: Analogous step for validation data.

Step 3: Sequences are processed for training data and for validation data. MODE variable ("train" or "validation") and BPP (boolean True or False) need to be set at the beginning of the script. It is possible to extract BPP information during this step. However, extracting BPP information will require a lot of memory in the subsequent steps (it can run only on machines with 128 GB RAM). Also, if BPP is used in training (for "submission-23"), then the inference is set up to calculate BBPs on the fly, which makes the inference script run 10 times longer for "submission-23" as compared to "submission-27". As the result of this step, small (partial) dataframes are written to "partial" files. There should be 17 files for "Quick_Start" training data and 4 files for validation.

Step 4: The "partial" files from the previous step are collected into one file. I set this up in this way due to historical reasons: I was struggling to save BPP information for later use in training, so I solved the problem by processing smaller chunks of the dataframe at a time (in previous step). I wanted to write these files into storage just in case (in case my script crashes). Since they are written as "partial" files, I collect them into one file for convenience.

Step 5: Processing test data will require a lot of time if the dataframe is processed at once. An analogous script took about 3 hours or more on my system. It is possible to re-write the code to process it in chunks, similar to training and validation data. However, I did not re-write it. Also, BPPs are not saved for test data because I was running out of time during the competition: instead, if BPPs are used in training, they will have to be calculated during inference. Saving BPP information into storage for test sequences could be beneficial if a lot of experiments use BPPs.

Step 6: Training. SUBMISSION_NUMBER (23 or 27) needs to be specified together with BPP_YES (whether the training will require BPPs). BPPs can be used for "submission-23" if BPP information was saved to storage in previous steps.

Step 7: Inference. Historically, I was writing smaller dataframes into storage. This script runs less than an hour for "submission-27" on my system and 8-10 hours for "submission-23" (because of calculating BPPs).

Step 8: The smaller dataframes are collected into one CSV ready for submission.

Step 9: This script generates reactivity vs. sequence plot for mutate and map sequences, according to "How to check if your model generalizes to long sequences" discussion.

Step 10: This script prepares data for the second plot (see next step).

Step 11: This script generates the secondary structure plot described in "How to check if your model generalizes to long sequences" discussion.

The naming of classes in this repository relies on numbers (e.g., DatasetEight is used for "submission-27") because I tried many variations of a class created for a specific purpose. There are additional datasets in datasets.py that could be used for experiments outside what was done for "submission-27" and "submission-23". DatasetTwelve is similar to DatasetEight, but it randomly perturbs reactivities according to their error. Note that columns "error_a" and "error_d" have to be preserved in the dataframe that is passed into DatasetTwelve (in the training script for "submission-27" these columns are dropped). DatasetEleven does analogous perturbation and can be used in place of DatasetTen (DatasetTen is used in "submission-23").

I tried training on more data: "Quick_Start" data together with the data outside of that set, filtered by its error: the rows where all reactivities had error greater than a certain number were dropped.

I also tried reactivity perturbation, following the idea described in the winning solution to the Kaggle OpenVaccine challenge [4].

The additional data and the reactivity perturbation might have improved the performance for my submissions, but these two modifications to training need to be tested separately and on more experiments to draw any conclusions.

There were also experiments with a more traditional encoder-decoder architecture, where the encoder was pretrained to predict reactivities from the sequence-combined-with-mfe-structure information, then these weights were inherited by the encoder-decoder. In these experiments, the same information was fed to the encoder and to the decoder. I observed an improved score on the public leaderboard; however, these models did not generalize well to longer sequences. I was not using rotary embeddings in these series of experiments, which might have been the reason why they did not perform well.

The starter notebook published by Iafoss [1] was crucial for me. Thank you so much for creating it.

Additionally, when including rotary embeddings, I relied on the code published by Arjun Sarkar in an article "Build your own Transformer from scratch using Pytorch" [5] as a starting point for further customization.

- Iafoss, “Rna starter [0.186 lb],” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/code/iafoss/rna-starter-0-186-lb

- H. K. Wayment-Steele, W. Kladwang, A. I. Strom, J. Lee, A. Treuille, A. Becka, R. Das, and E. Participants, “Rna secondary structure packages evaluated and improved by high-throughput experiments,” Nature Methods, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 1234–1242, Oct 2022. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01605-0

- J. Su, Y. Lu, S. Pan, B. Wen, and Y. Liu, “Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding,” 2021.

- J. Gao, “1st place solution,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/stanford-covid-vaccine/discussion/189620

- A. Sarkar, “Build your own transformer from scratch using pytorch,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://towardsdatascience.com/build-your-own-transformer-from-scratch-using-pytorch-84c850470dcb