PGQ is a Go package that provides a queuing mechanism for your Go applications. It is built on top of the postgres database and enables developers to implement efficient and reliable, but simple message queues for their services composed architecture using the familiar postgres infrastructure.

- Postgres-backed: Leverages the power of SQL to store and manage queues.

- Reliable: Guarantees message persistence and delivery, even if facing the various failures.

- Transactional: Supports transactional message handling, ensuring consistency.

- Simple usage: Provides a clean and easy-to-use API for interacting with the queue.

- Efficient: Optimized for medium to long jobs durations.

- Postgres: The

postgresjust works and is feature rich, scalable and performant. - SQL: You are already familiar with SQLm right? No need to learn anything new.

- Stack: You do not have to maintain/manage/administer/patch any additional message broker component.

- Simplicity: The

pgqis a simple and straightforward solution for your messaging needs. - Usability: The

pgqcan be used for many scenarios.

Of course, you can implement your own implementation or use other messaging technologies,

but why would you do that when you can use the postgres which is already there and is a proven technology?

See the benefits using pgq in the following video:

Even though there are other great technologies and tools for complex messaging including the robust routing configuration, sometimes you do not need it, and you can be just fine with the simpler tooling.

Pick pgq if you:

- need to distribute the traffic fairly among your app replicas

- need to protect your services from overload

- want the out-of-a-box observability of your queues

- want to use SQL for managing your queues

- already use

postgresand you want to keep your tech stack simple - don't want to manage another technology and learn its specifics

No need to bring the new technology to your existing stack when you can be pretty satisfied with postgres.

Write the consumers and publishers in various languages with the simple idea behind - use postgres table as a queue.

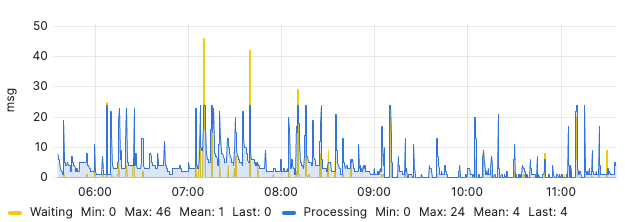

While using pgq you have a superb observability of the queue.

You can easily see the payloads of the messages waiting to be processed, but moreover payloads of both the currently being processed and already processed messages.

You can get the processing results, duration and other statistics pretty simply.

As the pgq queue table contains the records of already processed jobs too, you already have out of the box the historical statistics of all messages and can view it effortlessly by using simple SQL queries.

Pgq is intended to replace the specialized message brokers in environments where you already use postgres, and you want clean, simple and straightforward communication among your services.

- Every

queueis the single postgrestable. - You maintain the table on your own. You can extend it as you need.

- Publishers add new rows to the queue table.

- Consumers update the pgq mandatory fields of the rows in the queue table.

To install PGQ, use the go get command:

go get go.dataddo.com/pgq@latest

Prerequisites:

In order to make the pgq functional, there must exist the postgres table with all the necessary pgq fields.

You can create the table on your own with classic CREATE TABLE ..., or you can use the query generator to generate the query for you.

The generated query creates the queue table alongside with indexes which improve the consumer queries performance.

You usually run the setup commands just once during the queue setup.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"go.dataddo.com/pgq/x/schema"

)

func main() {

queueName := "my_queue"

// create string contains the "CREATE TABLE queueName ..."

// which you may use for table and indexes creation.

create := schema.GenerateCreateTableQuery(queueName)

fmt.Println(create)

// You may also use the "GenerateDropTableQuery" for dropping all the pgq artifacts (down migration)

}package main

import (

"context"

"database/sql"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

_ "github.com/jackc/pgx/v4/stdlib"

"go.dataddo.com/pgq"

)

func main() {

postgresDSN := "your_postgres_dsn"

queueName := "your_queue_name"

// create a new postgres connection

db, err := sql.Open("pgx", postgresDSN)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

defer db.Close()

// create the publisher which may be reused for multiple messages

// you may pass the optional PublisherOptions when creating it

publisher := pgq.NewPublisher(db)

// publish the message to the queue

// provide the payload which is the JSON object

// and optional metadata which is the map[string]string

msg := &pgq.MessageOutgoing{

Payload: json.RawMessage(`{"foo":"bar"}`),

}

msgId, err := publisher.Publish(context.Background(), queueName, msg)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("Message published with ID:", msgId)

}After the message is successfully published, you can see the new row with given msgId in the queue table.

Very often you want some metadata to be part of the message, so you can filter the messages in the queue table by it. Metadata can be any additional information you think is worth to be part of the message, but you do not want to be part of the payload. It can be the publisher app name/version, payload schema version, customer identifiers etc etc.

You can simply attach the metadata to single message by:

metadata := pgq.Metadata{

"publisherHost": "localhost",

"payloadVersion": "v1.0"

}or you can configure the publisher to attach the metadata to all messages it publishes:

opts := []pgq.PublisherOption{

pgq.WithMetaInjectors(

pgq.StaticMetaInjector(

pgq.Metadata{

"publisherHost": "localhost",

"publisherVersion": "commitRSA"

}

),

),

},

publisher := pgq.NewPublisher(db, opts)

metadata := pgq.Metadata{

"payloadVersion": "v1.0" // message specific meta field

}package main

import (

"context"

"database/sql"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"go.dataddo.com/pgq"

_ "github.com/jackc/pgx/v4/stdlib"

)

func main() {

postgresDSN := "your_postgres_dsn"

queueName := "your_queue_name"

// create a new postgres connection and publisher

db, err := sql.Open("pgx", postgresDSN)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

defer db.Close()

// create the consumer which gets attached to handling function we defined above

h := &handler{}

consumer, err := pgq.NewConsumer(db, queueName, h)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

err = consumer.Run(context.Background())

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

}

// we must specify the message handler, which implements simple interface

type handler struct {}

func (h *handler) HandleMessage(_ context.Context, msg *pgq.MessageIncoming) (processed bool, err error) {

fmt.Println("Message payload:", string(msg.Payload))

return true, nil

}You can configure the consumer by passing the optional ConsumeOptions when creating it.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

| WithLogger | Provide your own *slog.Logger to have the pgq logs under control |

| WithMaxParallelMessages | Set how many consumers you want to run concurently in your app. |

| WithLockDuration | You can set your own locks effective duration according to your needs time.Duration. If you handle messages quickly, set the duration in seconds/minutes. If you play with long-duration jobs it makes sense to set this to bigger value than your longest job takes to be processed. |

| WithPollingInterval | Defines the frequency of asking postgres table for the new message [time.Duration]. |

| WithInvalidMessageCallback | Handle the invalid messages which may appear in the queue. You may re-publish it to some junk queue etc. |

| WithHistoryLimit | how far in the history you want to search for messages in the queue. Sometimes you want to ignore messages created days ago even though the are unprocessed. |

| WithMetrics | No problem to attach your own metrics provider (prometheus, ...) here. |

consumer, err := NewConsumer(db, queueName, handler,

WithLogger(slog.New(slog.NewTextHandler(&tbWriter{tb: t}, &slog.HandlerOptions{Level: slog.LevelDebug}))),

WithLockDuration(10 * time.Minute),

WithPollingInterval(2 * time.Second),

WithMaxParallelMessages(1),

WithMetrics(noop.Meter{}),

)For more detailed usage examples and API documentation, please refer to the Dataddo pgq GoDoc page.

The message is the essential structure for communication between services using pgq.

The message struct matches the postgres table schema. You can modify the table structure on your own by adding extra columns, but pgq depends on following mandatory fields only:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

id |

The unique ID of the message in the db. |

payload |

User's custom message content in JSON format. |

metadata |

User's custom metadata about the message in JSON format so your payload remains cleansed from unnecessary data. This is the good place where to put information like the publisher app name, payload schema version, customer related information for easier debugging etc. |

created_at |

The timestamp when the record in db was created (message received to the queue). |

started_at |

Timestamp indicating when the consumer started to process the message. |

locked_until |

Contains the consumer lock validity timestamp. If this field is set and has not expired yet, no other consumer can process the message. |

processed_at |

Timestamp when the message was processed (either success or failure). |

error_detail |

The reason why the processing of the message failed provided by the consumer. NULL means no error. |

consumed_count |

The integer incremented by consumer retries is preventing the consumption of the message which can cause infinite processing loops because of OOM errors etc. |

Get the messages waiting in the queue to be fetched by consumer.

select * from queue_name where processed_at is null and locked_until is null;Get the number of messages waiting in the queue. A good candidate for the queue length metric in your monitoring system.

select count(*) from queue_name where processed_at is null and locked_until is null;Get the messages being processed at the moment.

select * from queue_name where processed_at is null and locked_until is null;Get the number of messages currently being processed. Another good candidate for metric in your monitoring system.

select count(*) from queue_name where processed_at is null and locked_until is null;Tip: You can use the pgq table as a source for your monitoring system and enable alerting for suspicious values. It is usually good not to monitor only the peak size but also the empty queues, which may indicate some troubles on publishers side.

The messages which have already been successfully processed.

select * from queue_name where processed_at is not null and error_detail is null;The messages which have already been processed, but ended with an error.

select * from queue_name where processed_at is not null and error_detail is not null;-- messages created in last 1 day which have not been processed yet

select * from queue_name where processed_at is null and created_at > NOW() - INTERVAL '1 DAY';

-- messages causing unexpected failures of consumers (ususally OOM)

select * from queue_name where consumed_count > 1;

-- top 10 slowest processed messages

select id, queue_name - started_at as duration from extractor_input where processed_at is not null and started_at is not null order by duration desc limit 10;The pgq internally uses the classic UPDATE + SELECT ... FOR UPDATE postgres statement which creates the transactional lock for the selected rows in the postgres table and enables the table to behave like the queue.

The Select statement is using the SKIP LOCKED clause

which enables the consumer to fetch the messages in the queue in the order they were created, and doesn't get stuck on the locked rows.

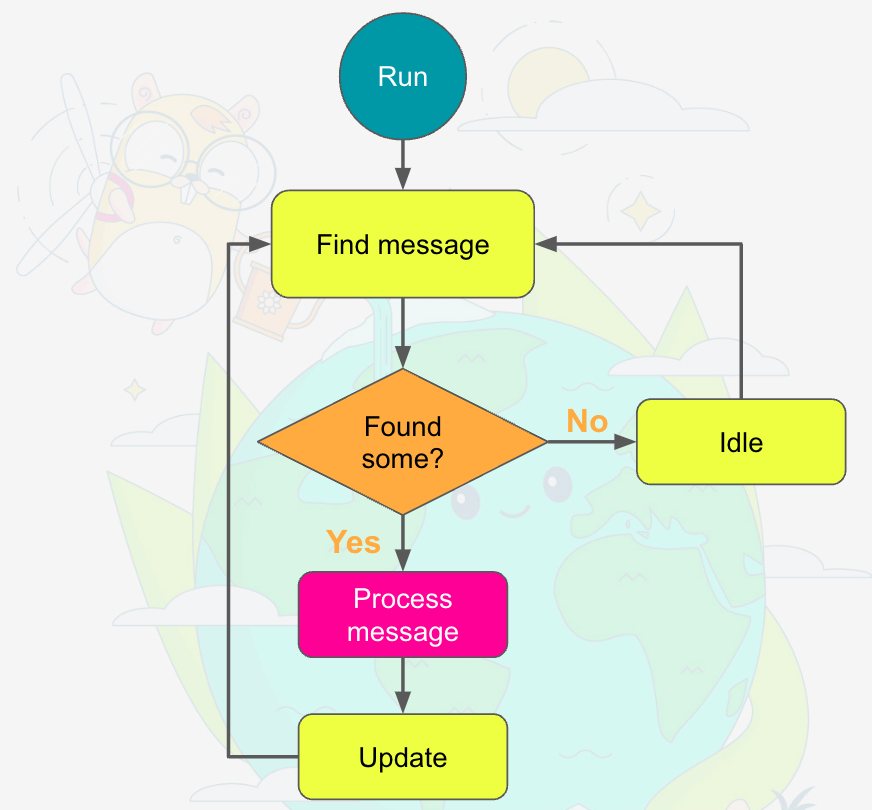

- When there is no message to be processed, consumer idles for a

polling intervalduration and then tries again. - When the consumer finds the message to be processed, it locks it by updating the

locked_untilfield with thelock durationtimestamp. - If the consumer fails to update the

locked_untilfield, it means that another consumer has already locked the message, and the current consumer tries to find the message again. - If the consumer successfully locks the message, it starts to process it.

- When the consumer finishes the processing, it updates the

processed_atfield with the current timestamp.

When using the pgq in production environment you should focus on the following areas to improve the performance:

Having indexes on the fields which are used for sending is the essential key for the good performance. When postgres lacks the indexes, it can very negatively influence the performance of searching of the queue, which may lead to slowing down the whole database instance.

Each queue table should have at least the following indexes:

CREATE INDEX IDX_CREATED_AT ON my_queue_name (created_at);

CREATE INDEX IDX_PROCESSED_AT_CONSUMED_COUNT ON my_queue_name (consumed_count, processed_at) WHERE (processed_at IS NULL);These indexes are automatically part of the output query of the GenerateCreateTableQuery function.

But if you create tables on your own, please make sure you have them.

Usually you do not need to keep the full history of the queue table in the database for months back.

You may delete such rows with the DELETE command in some cron jobs, but do not forget that DELETE is a very expensive operation in postgres,

and it may affect insertions and updates in the table.

The better solution is to use the postgres table partitioning.

The easiest way how to set up the partitioning is to use the pg_partman postgres extension.

If the query returns 0, you need to install the extension first, otherwise you're ready to partition.

SELECT count(name) FROM pg_available_extensions where name = 'pg_partman';- we create the

template tableto be used for creation of new partitions:

The template table must have exactly the same structure as the original queue, and it has the _template name suffix.

It must also contain the indexes so the partition derived tables have it too.

CREATE TABLE my_queue_name_template (id UUID NOT NULL DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(), created_at TIMESTAMP(0) WITH TIME ZONE DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP NOT NULL, payload JSONB DEFAULT NULL, metadata JSONB DEFAULT NULL, locked_until TIMESTAMP(0) WITH TIME ZONE DEFAULT NULL, processed_at TIMESTAMP(0) WITH TIME ZONE DEFAULT NULL, error_detail TEXT DEFAULT NULL, started_at TIMESTAMP(0) WITH TIME ZONE DEFAULT NULL, consumed_count INT DEFAULT 0 NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY(id, created_at));

CREATE INDEX IDX_CREATED_AT_TPL ON my_queue_name_template (created_at);

CREATE INDEX IDX_PROCESED_AT_TPL ON my_queue_name_template (consumed_count, processed_at) WHERE (processed_at IS NULL);- we create the partitioned table with the same structure as the template table, but with the partitioning key:

-- DROP the table if it already exists

DROP table IF EXISTS my_queue_name;

-- and let it be created like partman does it. This is the default queue to be used when no partitioned one is matched

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS my_queue_name

(LIKE my_queue_name_template INCLUDING DEFAULTS INCLUDING CONSTRAINTS INCLUDING INDEXES INCLUDING COMMENTS) PARTITION BY RANGE (created_at);- we instruct partman to create the partitions every day automatically:

SELECT partman.create_parent('my_queue_name', 'created_at', 'native', 'daily', p_template_table := 'my_queue_name_template';- we configure partman how to rotate the tables setting the 14 days retention period:

UPDATE partman.part_config

SET infinite_time_partitions = true,

retention = '14 days',

retention_keep_table = false,

retention_keep_index = false

WHERE parent_table = 'my_queue_name';